Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/2022/Opportunities for Van Panchayats in Uttarakhand, India in REDD+ Implementation?

Summary or Abstract

Van Panchayats (VP) or forest councils are one of the oldest and most important participatory forms of management. This is drawing attention to policy and legislative framework at the national and regional levels for their efficient working system. This is crucial for forest resources management at sustainable development eventually affecting livelihood opportunities, community development, and eco-restoration activities. REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) is a powerful climate change mitigation tool used for the forest sector in developing countries. Through successive agreements in UNFCCC COP finally, the Warsaw framework of REDD+ was adopted in 2013. Being a voluntary approach, countries were requested to submit the four elements in order to receive result-based payments.

This international mechanism is significant in building the current relations of direct drivers and indirect drivers and hence provides feasibility in terms of financial, administrative, and political ways. This is relevant to receive long-term benefits at the social, environmental, and economic levels. In this study, the detailed responsibilities and functions of VPs and has been diluted with time administratively. This study also demonstrates that REDD+ is one global opportunity that emphasizes stakeholder engagement by integrating various systems of traditional knowledge with a scientific inventory at a regional/local level. The affected stakeholders are the first-line defenders whose indigenous rights need to be guarded by upholding the REDD+ safeguard framework for the conservation of natural forests to gain carbon sequestration and biodiversity.

Description

REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) is one of the frameworks formulated by UNFCCC aiming to implement forest activities for sustainable management of forests, conservation, and enhancements of forest carbon stocks in developing countries. The REDD+ interventions are voluntary which is dependent on the national circumstances, indigenous rights, funding, etc. Warsaw Framework for REDD+ at COP 19 has provided the complete structure to progress REDD+ activities in a long term.

For its success, recognition of different stakeholders, policy framework, benefit sharing mechanism, forest tenure regimes, and financial resources needs to be reviewed and modified accordingly for the first-line defenders of forest resources.

In India, legally three types of forest are being managed, and one (village forests) of them is under Van Panchayats (VPs)- "a local autonomous institution". They are one of the oldest participatory forms of forest management with a set of rules for subsistence rights for small timber, fuel, fodder, etc. located in Uttarakhand, India. Legally came into existence in 1931 after a long historical battle for their right over boundless forest resources. The VP (forest council) forests are owned by the village communities and the rural people’s dependency lies only on the jurisdictional common property following strict bureaucratic and administrative arrangements. Figure 1 has shown the number of Van Panchayats in Uttarakhand state of India.

There exists a gap that does not allow us to address the drivers of deforestation and forest degradation and make effective and efficient use of forest resources for sustenance.

The objective of REDD+ is an opportunity for VPs to bring congruence to traditional ecological practices in a productive manner. To achieve REDD+ goals, governance, and security in terms of tenure rights and institutional arrangements is urgently needed to be aligned for sustainable natural resources management for VPs.

Keywords

REDD+, Van Panchayats, women, phytosociology, green enterprise, Uttarakhand, India

Phytosociological analysis

Each VP is recognized by its unique type of resources (forest type and quality) and a class of owners/managers bringing differences in the area of forest commons structure and functioning too.

For REDD+ to be in place and access the carbon rights, result-based actions are required to be fully measurable, reportable, and verifiable (MRV). To attain result-based incentives, it is crucial to understand the existing resources and their management practices and usage patterns. This includes regeneration status, crown cover, number of lopped branches/trees, fodder extraction, grazing, etc. of different types of forest.

REDD+ implementation requires a thorough analysis of the distribution of species, species diversity, regeneration, diversity index, dominance diversity index, and importance vegetation index are one of the best indicators of biodiversity which brings a clear picture of the alpha, beta, and gamma biodiversity. The heterogeneity is also present in each VP, especially in terms of abundance, frequency, and density.[2] This will bring modifications in scientific management with traditional ecological knowledge embedded in forest management practices to enhance the carbon sequestration rates and biodiversity between the reference and result period.

The commonest type of species present in the VPs is Chir Pine (Pinus roxburgii) and Banj Oak (Quercus leucotricophora), Deodar (Cedrus deodara), Himalayan birch (Betula utilis), Junipers, Rhododendrons, Rianj (Q. lanuginose), and Tilonj (Q. floribunda) etc[3].

Tenure arrangements

The legal existence of VPs was in 1931 though the legal battle for access to resources and sacred places continued for a long time until recommended by the Kumaon Forest Grievances Committee. In 1931, upon the recommendation of the committee brought devolutionary powers for own subsistence (“such as fodder, leaves for animals bedding, grazing space for their animals, fuelwood, and timber for house construction and agricultural implements”)[3] in Forest Panchayat Act (section 28(2) under the 1927 Indian Forest Act).

The Van Panchayat Rules of 1976, 2001, and 2005 have brought significant modifications in the framework of the responsibilities and authority of VPs covering five years of tenure. As per rules the people entitled to benefits makes rules for daily management activities but still lack complete authority in their implementation[4].

Major changes were observed from Van Panchayat Rule 1976 to 2005, the people’s authorization was entrusted to the forest department. This includes the micro plans for five years that need the approval of the Divisional Forest Officer (DFO) (Panchayat Van Vikas Adhikari) and annual plans that need approval from the forest ranger (Sahayak Panchayat Vikas Adhikari). Prior approval is also needed by DFO to sell the forest produce[4][5].

Further, Gram Panchayat (responsible for the management of civil and soyam forests on behalf of the revenue department) chooses the head of the VP instead of holding elections that need to be held after every five years. Therefore, restricting their participation in controlling and using the resources. This raises the concern about changing the mechanism of the functionaries of the government especially giving traditional rights to solve the complex forest problems and revitalize the participatory form of management by holding the authoritative control of the forest resources.

Institutional/Administrative arrangements

The Government of India has a complete framework for the policy and legislative frameworks for the conservation of natural resources which can safeguard REDD+ implementation at the national level but is still constricted to applying Cancun Safeguards for REDD+ at the regional level implementation. In order to enhance the capacity and capabilities of the indigenous for full active participation in terms of usage of knowledge and practice rights for consistent conservation of the natural resources.

All villagers are members of VP after the approval of a Sub-Divisional Magistrate under the State Revenue Department. There is also a management committee selected by the general body (villagers) and a Sarpanch (head) is selected for a period of five years through the local election. Currently, there are 12,064 VP established in Uttarakhand. These Panchayats manage an area of 523289 hectares and contributes around 14 percent of the state area of forest cover. They are distributed in 11 districts of the Uttarakhand state[4].

The main responsibilities of the Van Panchayats are

- To prepare management plans focusing on the protection of forests and identifying illegal activities. Stand harvesting, approval of the management plan, and other directives need permission from the forest department.

- Violations in terms of encroachment of land are required to be informed and assist in taking effective measures.

- To encourage the forest management practices such as forest fire control and prevention and other eco-restoration activities[6].

The modifications in the Van Panchayats rules with time had narrowed the participation of the community and their powers in exercising control of the resources management. The VP has to follow the instructions of DFO orders for the conservation and improvement of forest resources.

Major changes were encountered from the Van Panchayat Rules, 1931 delegating no officials from the state forest department for the working plans to Van Panchayat Rules, 1976 with one special officer to five and more than five in 2001 and 2005 bringing “the sense of belonging.”[4] Additionally, the Sub-Divisional Magistrate has the power to remove a member of the VP and infuse a sense of bureaucracy and decentralization. The duties VP varies with the villages but needs to participate in fire control, 2) report VP rule infractions to the Forest Council, and 3) tree-planting efforts.

The debates on REDD+ activities have been dominated by the noncompliance of the community rights in terms of ownership rights and carbon tenure and inequitable benefit-sharing mechanisms. Reduced bureaucratic support and accountability, "excessive powers and responsibilities” instead of a “strong tradition of collective decision-making” is responsible for reduced transparency and excessive burden of responsibilities is a “major disincentive for taking up the leadership of a VP.”[4]

Affected Stakeholders

Indigenous communities managing the forest resources and deriving the output for their livelihoods are the primary stakeholders. Strategically, REDD+ bridge the gap between the indigenous community’s rights & practices with their result-based incentives. For long-term management of natural resources, indigenous communities and REDD+ activities need to be synchronized to generate green enterprise sustainably. The “ National REDD+ Strategy will support the empowerment of youth as Community Foresters, who can be engaged effectively in assisted natural regeneration, soil and moisture conservation, harvesting, thinning and hygienic removals, forest nurseries and raising of quality planting stocks, and prevention and control of forest fires, pests, and diseases, and the spread of invasive alien plant species through the green skill development program.”[7].

The indigenous community's crucial role in the maintenance of the forest ecosystem was realized by the Government of India and enacted The Scheduled Tribes and other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, at the central and state level, it will grant rights and occupation in forest lands to forest-dwelling scheduled tribes and other traditional forest-dwellers through generations. As per REDD+ elements, it adheres to the safeguards of the local communities with respect to land ownership and non-timber forest products[8]. The point of concern is to understand the concept to its core while implementing REDD+ activities and during post-REDD+ Implementation.

Interested Stakeholders

For effective and efficient REDD+ execution throughout the period, it is necessary to engage all stakeholders for the consistent development of forest resources. The state forest department and state revenue department are interested stakeholders. State revenue department shows their participation “for overseeing elections and established procedures and maintaining land records”. Under Panchayati Forest Rules, 2001, the state forest department demands 20 percent of the micro plan cost from the local community[6].

The National REDD+ Policy of India will follow all the relevant UNFCCC decisions and an institutional arrangement will be followed for REDD+ implementation (figure 2). Under this institutional framework, the role has been defined for all stakeholders initiating from the central government to the state government level, at the forest institution level, and civil society apart from the indigenous community. National Designated Entity has also been established by the Government of India. The function of the NDE will be to "serve as a liaison between the UNFCCC Secretariat and the relevant bodies under the Convention on REDD+ issues with Joint Secretary (Climate Change) in the Ministry MoEFCC as Focal Point for REDD+". The chairman of the NDE is the Director General of Forests and Special Secretary of the Ministry of Environment, forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC), the other members are from Indian Forest Services at both the central and state level. The REDD+ experts representation at all levels will be there in Thematic Advisory Committee and REDD+ Technical Working group too[7].

Discussion

Van Panchayat shares a strong bond with their territory but a series of amendments through Van Panchayat rules had added to dysfunctionality due to the dilution of decision-making powers to manage their resources independently.

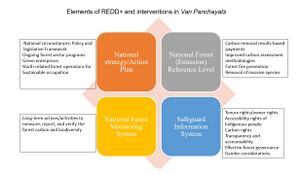

REDD+ is one of the mitigation options for climate change for developing countries. REDD+ is an important pillar to grow a symbiotic relationship between institutional arrangements (interested stakeholders) and traditional ecological knowledge (affected stakeholders)[9]. For REDD+ to implement, it is crucial to address the challenges at the national level and regional levels for community rights, policy, finance, and the lack of capacity of the stakeholders. For REDD+ proper functioning, it is necessary permanence, leakage, additionality, and strong community forest management laws are needed to be placed properly. REDD+ brings an opportunity to set a formalized and secure tenure system” which is important for participation in REDD+ activities in the Van Panchayats [10]. There are four elements that complete the structure of REDD+ intervention successfully given in Figure 3.

REDD+ and safeguarding the rights of the indigenous people go parallel in tackling the challenges deriving from climate change and increasing complexity with the poor framework for environmental governance. International Labour Organization (ILO) is at the forefront to bring social justice and promote a sustainable economy. Similarly, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) also strives to protect the rights of the people. The "joint production of knowledge" between REDD+, ILO, and UNDRIP is important to bring coherence in actors, networks, and forest practices for better livelihood opportunities, greater independence, and commitment to forest mitigation and adaptation activities[11].

Critical Issues and their assessments

India is in the readiness phase for REDD+ implementation and submitted National REDD+ Strategy and National Forest Reference Level. With a lot of opportunities existing, there are many challenges to its implementation. Other than tenure rights, the role of women at different decision-making levels in participatory forest management is crucial. Further bringing “biological and cultural essentialisms”. Van Panchayat Rule, 2001 has recognized and “included a provision for half the number of women members in VP.” The practice of respecting the “regulatory landscape” and “effectively safeguard biodiversity and human well-being”. REDD+ is one of the approaches that can revitalize the working system of VPs [12][13]. Chipko Movement and Maiti Andolan are initiatives systematically led by women to deepen the connection between forests and communities with space and time[14].For REDD+ activities execution, gender-centered sensitivity needs to be developed for effective forest governance.

The Van Panchayat Rule, 2005, administratively followed a top-down approach where the DFO role is superior over the forest councils with regards to conservation and management of resources instead of utilizing traditional ecological knowledge to control forest fire, invasive plant species, and livelihood opportunities sustainably.

The public-private partnership with the indigenous community is another innovative approach needed to overcome the challenge of the sustainable management of forests through consistent finance availability, provision of quality planting stocks of indigenous forestry species, and assistance in other alternate green investment enterprises [7]

Forest Management is local and community-centric. The contribution is crucial in the maintenance of the forest and improving institutional architecture in the form of skill development programs and capacity development. As per National REDD+ Strategy, indigenous people's organizations are also encouraged to participate in the National REDD+ Governance Structure (NGC-REDD+). Devolving full responsibility for forest management to the community also includes result-based payments directly for reversing deforestation. The payment should be processed directly to the indigenous community. Based on performance, essential mechanisms for economic returns should be safeguarded in the form of a fair, equitable, transparent, and proportionate manner.

Effective governance requires the participation of each stakeholder to form a democratic arrangement. that provides liberty to the indigenous community to take decision-making powers in REDD+ activities. The vision of REDD+ is to create a vision of bringing a green economy at each village level. Innovation and new investments in forest-centric livelihood people with the power of retaining the interests of women and tribal people are inevitably required in the process of REDD+ execution. This process will persist in the commitment to bring REDD+ projects successfully to bring a shift from subsistence benefits to sustainable benefits. The critical role of VPs needs to be recognized at the project level, state level, and central level of governance to equip the VPs as strong professional, powerful and independent institutions just like other community forest institutions[15].

Recommendations

Results-based REDD+ implementation activities require a well-developed conflict resolution mechanism between the locals and the government. For successful REDD+ interventions, it is essential to target key drivers such as the tenure system and institutional mechanism, etc. in relation to four key elements for the equitable distribution of benefits among stakeholders[16].

Capacity building workshops at the grassroots level institutions including frontline staff of the forest department and communities to implement REDD+ activities. The new modalities of governance are essentially needed to bring concerns and independence of the community to prepare for REDD+ execution. This involves the reconstruction of the governance from the central to the local level by bringing a thoughtful analysis of the functions and roles played by each actor/stakeholder for REDD+ success sustenance. Additionally, revitalizing each VP, it is required that transparent and accountable governance is needed to realize the goals and "decentralization of power"[15] from state government proprietorship to the village community.

Policies, programs, and legislative frameworks in the conservation-centric forestry sector have to be conducive to generating the enabling environment for the REDD+ implementation successfully for a long-term period[17].

The benefit-sharing mechanism should be explicitly mentioned before the start of the program. The public-private partnerships are a solution due to the lack of multilateral organization finance availability that has the potential to create green jobs is one of the ways to protect the forest and become climate resilient and safeguard the rights of the VPs, especially youth. Therefore, some inevitable modifications can bring successful visible participation of Van Panchayats to achieve regional and global goals.

| Theme: Van Panchayats and REDD+ Implementation | |

| Country: India | |

| Province/Prefecture: Uttarakhand | |

| City: Garhwal and Kumaon region | |

This conservation resource was created by Gurveen Arora. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0. | |

References

- ↑ Gupta, Mukesh (2007). "Promoting Self Sufficiency Through Carbon Credits From Conservation and Management of Forests".

- ↑ Saxena, A. K., & Singh, J. S. (1982). A phytosociological analysis of woody species in forest communities of a part of Kumaun Himalaya. Vegetatio, 50(1), 3–22. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00120674.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Stevens, M. and Krishnamurthy, R. (2022). ‘If there is jangal (forest) there is everything: Exercising stewardship rights and responsibilities in van panchayat community forests, Johar Valley, Uttarakhand, India’, in Bulkan, J. et al. (eds) Handbook of Community Forestry. Routledge, pp. 372-396. Retrieved from https://doi.org/1 0. 432 4/ 9780367488710

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 B.S. Negi, D.S. Chauhan and N.P. Todaria, ‘Administrative and Policy Bottlenecks in Effective Management of Van Panchayats in Uttarakhand, India’, 8/1 Law, Environment and Development Journal (2012), p. 141, available at http://www.lead-journal.org/content/12141.pdf

- ↑ Agrawal, A. (2001). The regulatory community. Mountain research and development, 21(3), 208-211. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1659/0276-4741(2001)021 [0208:TRC] 2.0.CO;2

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Nagahama, K., Tachibana, S., & Rakwal, R. (2022). Critical Aspects of People’s Participation in Community-Based Forest Management from the Case of Van Panchayat in Indian Himalaya. Forests, 13(10), 1667. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13101667

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 MOEFCC (2018). "National REDD+ Strategy India" (PDF).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India (2007). "The Scheduled Tribes and other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006" (PDF). Invalid

|url-status=https://forestrights.nic.in/(help) - ↑ Aggarwal, A., Das, S., Paul, V., & TERI. (2009). Is India ready to implement Redd Plus? A preliminary assessment. Retrieved, from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ashish-Aggarwal-7/publication/278021235_Is_India_ready_ to_implement_REDD_Plus_A_ preliminary_assessment/links/5579118708ae752158703ee3/Is-India-ready-to-implement-REDD-Plus-A-preliminary-assessment.pdf

- ↑ Rawat, R. S., Arora, G., Gautam, S., & Shaktan, T. (2020). Opportunities and Challenges for the Implementation of REDD+ Activities in India. Current Science, 119(5), 749. https://doi.org/10.18520/cs/v119/i5/749-756

- ↑ World Wide Fund For Nature and International Labour Organization (2020). "NATURE HIRES: How Nature-based Solutions can power a green jobs recovery" (PDF). line feed character in

|title=at position 41 (help) - ↑ Newton, P., Schaap, B., Fournier, M., Cornwall, M., Rosenbach, D. W., DeBoer, J., Whittemore, J., Stock, R., Yoders, M., Brodnig, G., & Agrawal, A. (2015). Community forest management and REDD+. Forest Policy and Economics, 56, 27–37. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2015.03.008

- ↑ Nagahama, K., Tachibana, S., & Rakwal, R. (2022). Critical aspects of people’s participation in community-based forest management from the case of van panchayat in Indian Himalaya. Forests, 13(10), 1667. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3390/f13101667

- ↑ Tomaselli, M. F., & Hajjar, R. (2011). Promoting community forestry enterprises in national REDD+ strategies: A business approach. Forests, 2(1), 283–300. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3390/f2010283

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Tompsett, C. (2014). Community Forests for Business or Subsistence? Reassembling the Van Panchayats in the Indian Himalayas. Forum for Development Studies, 41(2), 295–316. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2014.901242

- ↑ UN-REDD (2016). "Towards a Common Understanding of REDD+ Under the UNFCCC: A UN-REDD Programme Document to Foster a Common Approach of REDD+ Implementation. Technical Resource Series-3, International Environment House, Geneva, Switzerland" (PDF). line feed character in

|title=at position 68 (help) - ↑ Badola, R., Hussain, S. A., Dobriyal, P., & Barthwal, S. (2015). Assessing the effectiveness of policies in sustaining and promoting ecosystem services in the Indian Himalayas. International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management, 11(3), 216-224. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/21513732.2015.1030694