Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/2021/FireSmart in Quesnel as a model for community forest practices on privately owned land

As mega-fires become part of the new normal for British Columbia’s forestry towns, efforts to mitigate their spread are forcing communities to take action. Creating fire-adapted communities requires the general public to become partners in managing wildfire risk.[1] Quesnel is one such town that is galvanising public action to face the threat of wildfires spreading within their community. It is an example of a community where the municipal government, private homeowners and the forestry industry are forming a united front to tackle this 'wicked problem'.

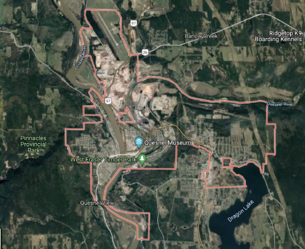

Quesnel (pronounced kwah-nell) sits 630 km north of Vancouver along the Cariboo highway that follows the Fraser River through British Columbia. Quesnel is a forestry town with a population of just over 12,000, the majority of whom are over 55. As of 2016, unemployment was at 10%. [2]

Community forestry can take many different forms.[3] What makes FireSmart interesting as a case study is that most management practices occur on private land, to the collective benefit. It could be a lesson in using community forest practices on a larger local scale, without the need for tenure licences or agreements.

| Theme: Community wildfire prevention | |

| Country: Canada | |

| Province/Prefecture: British Columbia | |

| City: Quesnel | |

This conservation resource was created by Chiara Milford. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0. | |

The British Columbia mega-fire context

The 2017 wildfire season was one of the worst in British Columbia’s history. More than 1.2 million hectares burned. The Plateau Complex of fires on the Chilcotin Plateau covered a combined area of 545,151 hectares, making it the largest fire in BC’s recorded history.[4]

The Government of British Columbia estimates about 685,000 hectares of forests are at high risk, with a heightened build-up of vegetation increasing the amount of potential fuel for a forest fire. 970,000 hectares are at moderate risk of sending embers into BC communities during a wildfire.[4]

“Living in a forested area means, eventually, communities will need to contend with a wildfire. We must focus on preparedness, prevention and mitigation, to minimise wildfire impacts. All levels of government, industry and the public have a role to play." - Krista Dunleavey, fire centre manager with the BC Wildfire Service.[4]

The 2017 Green Mountain fire (which eventually merged to form the Plateau Complex fire) threatened to wipe out the communications towers that service Quesnel. If it had, the town would have been evacuated. The area around the towers had been cleared of debris just days before. Quesnel only has a volunteer firefighting department, with four fully qualified paid staff, 38 volunteers, three fire engines and a structural fire trailer. During huge scale fire events like these, they have to call on help from outside the community, even as far as Australia. [5][6]

FireSmart™️ in Canada

FireSmart started in Alberta in 1990. Now, FireSmart works with local governments and private individuals, focusing on fire mitigation where wild-lands and human development come together (the wild-land/urban interface). It is a non-profit organisation, funded primarily by federal and provincial governments. FireSmart Canada has a partnership with The Co-operators Group, an insurance and financial co-op, as well as the National Fire Protection Association. As of 2021, FireSmart is part of the program of the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre.[7]

On their public-facing website, FireSmart states their goals are, “to improve communication with stakeholders; and to organize programs and assets into a logical, manageable structure based on three pillars – homeowners, neighbourhoods and communities.”[7]

FireSmart provides and distributes manuals for homeowners published by the provincial government. The latest runs at 32 pages and uses illustrations to explain how wildfires spread and why homes burn. Photographs demonstrate the actions homeowners can take in order to make their homes more resilient to fire. It provides tools and information to help homeowners make their own decisions and feel part of a community attempting to grow their resilience to fire.[8]

$10,000 Fire Smart grants are available from FireSmart Canada for community-lead planning on private land, distributed among one local municipality per year. Quesnel is hoping to apply for such a grant.[5]

The public response

An independent review by the provincial government detailing the unprecedented floods and fires in 2017 says there is a "need for greater public awareness campaigns, particularly as they relate to cigarettes, prevention, property and response responsibilities."[4]

According to this report, nearly eight in 10 respondents were familiar with FireSmart activities."[4] However, another survey of 2,427 people from across Canada by Mohamed Ergibi in 2017, found that the majority of survey respondents had not heard of FireSmart (77%) and only a fraction had engaged in FireSmart activities.[9]

Ergibi found that the majority of respondents (1,084 people) believed that homeowners are responsible for their own protection. 45.6% of respondents felt that homeowners were responsible for protecting private property. Collectively, 45.1% of respondents believed protecting private property is the responsibility of local government (16%), the provincial government (14.8%), and the community (14.3%).[9]

Low-cost, low-effort options such as mowing and watering grass, and moving firewood piles away from structures are more readily adopted by homeowners. Ergibi found that older women, those with larger lots of land, those who had been evacuated, and those who talked with a neighbour about wildfires all had higher risk mitigation levels.[9]

It is impossible to definitively quantify how many homes have taken measures to prevent the spread of fire to their property - the data is not collected. According to Erin Robinson at Quesnel's Forestry Innovation Centre, 140 homes and buildings in Quesnel and area have been assessed by a Local FireSmart Representative for fire hazard, and 31 FireSmart rebates have been fulfilled.[10]

Wildfire protection in Quesnel, B.C.

Forests are central to the livelihoods of the City of Quesnel. The Quesnel Timber Supply Area is 1.28 million hectares. The current allowable annual cut for the Quesnel timber supply area is 2,607,000 cubic metres. The trees are mainly sub-boreal pine and spruce, with lodgepole pine and trembling aspen forests - mainly fire-prone species.[11]

The community has a vested interest in protecting the forests that surround their communities, and obviously, an interest in protecting their homes from fire. Nonetheless, there was some pushback from the public when the municipality decided to intervene with wildfire proofing. "When I first started in 2019 there was a misunderstanding to set up a program that’s not part of a normal city function. Land management is not our jurisdiction, but now people understand,” said Erin Robinson, Forestry Initiatives Manager.[10]

Since 2018, 188 hectares of Crown land have been cleared of debris by hand and new trails have been put through fuel managed parts of the forest. Another 60 are slated to be treated this winter. [10]

Governmental land-management agencies are not well positioned to coordinate the integrated partnerships necessary to achieve fuel-management goals, because they are often restricted by jurisdictional boundaries and institutional mandates.[1]

Quesnel's Community Wildfire Protection Plan (CWPP)

Most forest-based communities in Canada now have a wildfire protection plan, developed by the local council and various stakeholders.

In the wake of the unprecedented wildfires of 2017 the City of Quesnel developed a Community Wildfire Protection Plan, published in 2018.[5] It is the cumulation of a multi-party meeting that took place involving representatives from the local forestry industry (West Fraser and Tolko), provincial fire service personnel, First Nations members (Lhtako Dene and ?Esdilagh) and municipal leadership. At the time, no fuel management initiatives were taking place in Quesnel.[12]

"It is everyone’s responsibility, from the home owner to the Mayor and Council/Chief and Council to take measures to mitigate fire risk” - B.C. Wildfire Services [12]

The plan includes suggestions for fuel management communication and education programs and laying out examples (like a FireSmart day) of how to increase public engagement. The City of Quesnel wants to ensure no new developments or subdivisions are established without adequate wildfire threat reduction efforts put in place before construction begins. Separating homes and other structures from the forest environment involves establishing FireSmart landscaping around the structure so a wildfire cannot spread directly up to the structure. A minimum of 10 meters of FireSmart landscaping from the structure to unmanaged forested land is recommended in the CWPP. [5]

People and their power

Local leadership

Bob Simpson - Mayor of the City of Quesnel

Mayor Simpson has made it his mission to revolutionise the forest industry in Quesnel.[13] When he ran for mayor of Quesnel for the first time in 2014, he won 70 per cent of the vote against the incumbent, Mary Sjostrom.[14]

Certain property owners were worried that implementing FireSmart measures would completely remove the presence of nature around their homes. To respond to their concerns, Simpson and council set up a demonstration of FireSmart principles on some of the airport's land. This included a trail system with interpretive signage to demonstrate how specific strategies might look. There are now more FireSmart accessible trails around the community which have been successful at limiting surface fire intensity.[15]

“It was crucial for the community to adopt this two-fold strategy as there was no point investing in our vulnerable territory on public lands if our risk around private properties remained high.” - Mayor Bob Simpson [15]

Erin Robinson - Forestry Initiatives Manager at the Forestry Innovation Centre (FIC)

The Forestry Innovation Centre is a $3 million initiative opened in 2018 to launch a paradigm shift from logging two-by-fours to fostering a healthy ecosystem. It’s the only one of its kind anywhere in the province. Part of the Forestry Innovation Centre’s mandate is to bring together stakeholders from industry, the community, and First Peoples. While Robinson doesn't hold power over any part of the community, she is the author of several reports on forestry in Quesnel and well-known within the industry. [10]

"You need to have so many people work together on these problems. There is real power in bringing people together and asking these questions.” - Erin Robinson, FIC.[10]

Homeowners

Cost is a big factor in an individual deciding to fire-proof their home. [9] FireSmart pamphlets demonstrate the methods homeowners can use to better protect their homes from wildfires with three levels of financial undertaking ranging from no cost to around $3,000. [16] Even though financial costs can be relatively low, there is a significant amount of time required to do things like mow the lawn and clear leaves and debris from a garden, which places a burden on those who are time-poor.

If the public don't act, it places the burden on often underfunded local volunteer fire departments. "We need the public to understand their attitude towards us affects us. We do everything we can to protect homes and infrastructures, so it’s frustrating," says firefighter Matt Duran from BCWS.

"50% of wildfires are human-caused. It’s been like that since forever. No matter how much education and awareness there is."

- Matt Duran, BCWS Firefighter [6]

The forestry industry

West Fraser started in Quesnel in the 50s and grew into the biggest sawmill company in the world. Its operations HQ remains in Quesnel. It employs 1,300 people in the community. Now they are investing more in the managed thinning of trees, instead of the old clearcutting model. A thinner, patchwork forest, is less prone to all-consuming mega-fires.[17] The industry benefits greatly from fuel-management practices because it protects their valuable timber, as well as allowing them to cut more regularly.

Wildfires don't care about tenure

In Quesnel, private homes, municipal buildings, the hospital, the airport, schools, recreation areas, utilities, and volunteer fire departments all find themselves in the interface zone, where embers could jump across from the forest canopy to a human-built space.[5]

Landowner awareness and buy-in are the only options for reducing the wildfire hazard to their own property. Over 60 percent of the land mentioned in Quesnel's Community Wildfire Protection Plan are privately owned.[15] It comes down to individual homeowners deciding to do what they can to protect their property.

The land-base for Quesnel's proposed community forest and First Nation Woodland License also falls within the interface area. Quesnel's priority wildfire threat areas listed are all located on BC Crown or municipal Crown land.[5] But most of the land that FireSmart focuses on is privately owned.

An issue with FireSmart's focus on private homeowners is that landscape vegetation treatments and home ignition resistance needs to be maintained and perpetuated across time and changes in property ownership.[1] In Quesnel, the municipality is working to fuel-treat public lands, while the industry is doing the same with their timber licensed land. The rest falls to private homeowners: it relies on a group of people seeing the need to change and taking it upon themselves to make that change.[10]

Moving forwards

The problem of wildfires spreading to homes is a solvable one. In the immediate aftermath of the 2017 Fort McMurray fire in Alberta, one of the co-creators of Canada’s FireSmart program, Alan Westhaver, looked into the reasons why some homes survived. His findings were simple: homes that had taken FireSmart measures were less likely to have burned.[18]

"Simple solutions that already exist must be put into place to mitigate hazards at the doorsteps and in the backyards of our neighbourhoods; applied by property owners to reduce the vulnerability of homes to ignition." - Alan Westhaver, FireSmart co-creator [18]

FireSmart is recommended in nearly every wildfire report as a way to prevent the spread of dangerous fires and stop the destruction of lives and property. The Government of British Columbia recommends that the province, “Fund and foster a revitalized FireSmart program and encourage dynamic partnerships with local and First Nations governments as well as the participation of large private landholders. [And] expand the community forest program to other communities where interest and capacity exist."[4]

Local municipalities and governments should manage vegetation in public spaces as ‘demonstration sites’ to promote low-risk landscaping alternatives to local residents.

A relatively easy fix proposed in Quesnel’s Community Wildfire Protection Plan is to promote deciduous trees (i.e., aspen) that are favourable as the high moisture content and lack of resins means they are not as susceptible to wildfires as conifers and pine. [5]

Communication

FireSmart information needs to be distributed to the private landowners in established developments with unacceptably high wildfire threat.[5] When surveyed, people talked about greater education on FireSmart: that rather than becoming mandatory, incentives are offered by insurance companies in exchange for participation. There are no consistently effective sources of information, whether radio, television or brochures. [9]

Westhaver suggests that demonstrating the pathways fire uses to ignite a home in a visual form will encourage homeowners to adopt simple FireSmart practices and result in lowering the vulnerability of their home or neighbourhood.[18] Visualisations could also aid the real-time assessment of how management, community, or individual decisions may affect the immediate or cascading consequences of fires. [1]

“I’m feeling safer here now. I’m relieved that the city is doing FireSmart. It’s changing the community by building a sense of safety.” - Erin Robinson, FIC

Discussion

Equity and communication

FireSmart is not necessarily equitable. Older residents and people with less mobility (the most vulnerable in a wildfire event) are the least able to take action on their property themselves. [19] Municipal governments need to provide practical financial support for those who are unable to protect their homes themselves. This would make FireSmart more of a community forest practice; involving all aspects of the community and empowering them to engage in fuel-management.

FireSmart as it is today is quite a top-down approach to forest practices. People are reluctant to take advice from governments, even when it comes from solidly scientific evidence and serves their benefit. If FireSmart was less prescriptive and more about the empowerment of homeowners to defend their properties from wildfire, then perhaps uptake could be improved. It could involve more peer-to-peer engagement, with neighbours informing each other, rather than relying on government communication flyers. People respond better to wildfire information received from local volunteer fire departments and county wildfire specialists. [9]

It is important to note that FireSmart does not mean stopping wildfires from starting altogether, but it allows firefighting crews to intervene and prevent it from devastating homes and risking lives. Without precautionary actions by property owners to significantly reduce the vulnerability of structures to ignition, the likelihood of wildland-urban fire disasters is likely to continue.[18]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Smith, A. M. S et al. (2016). The Science of Firescapes: Achieving Fire-Resilient Communities. BioScience, 66(2), 130–146. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biv182

- ↑ "Stats Can Census Information".

- ↑ "Forests and people: 25 years of community forestry".

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 "Addressing the New Normal: 21st Century Disaster Management in British Columbia" (PDF).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 "Quesnel and Surrounding Area Community Wildfire Protection Plan" (PDF). horizontal tab character in

|title=at position 48 (help) - ↑ 6.0 6.1 Duran, M. (2021, October 16). What is FireSmart and how is it doing in Quesnel? (C. Milford, Interviewer) [Personal communication].

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "What is FireSmart".

- ↑ "BCWS Homeowner FireSmart Manual" (PDF).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Ergibi, M. (2018). Awareness and adoption of FireSmart Canada: barriers and incentives. https://harvest.usask.ca/bitstream/handle/10388/8498/ERGIBI-THESIS-2018.pdf

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Robinson, E. (2021, October 25). What is Quesnel’s Forestry Innovation Centre doing? (C. Milford, Interviewer) [Personal communication]

- ↑ "Quesnel Timber Supply Area".

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Quesnel CWPP meeting Notes as of May 28, 2017" (PDF).

- ↑ Simpson, B. (2021, November 6). What are your hopes for the forestry industry within Quesnel? (C. Milford, Interviewer) [Personal communication].

- ↑ "Civic info BC - Quesnel voting results".

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 "Cities adapt to extreme wildfires: Celebrating local leadership. Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction" (PDF).

- ↑ "FireSmart - 3 Steps to Wildfire Protection" (PDF).

- ↑ Hessburg, P. (2021, November 16). How can communities tackle wildfires? (C. Milford, Interviewer) [Personal communication].

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 "Why some homes survived: Learning from the Fort McMurray wildland/urban interface fire disaster" (PDF).

- ↑ Scuffi, L. (2021, October 1). How is Quesnel changing forestry practices? (C. Milford, Interviewer) [Personal communication].