Course:CONS200/2023WT1/Ups and Downs of Wildlife Conservation: Evidence from Rhino (Rhinoceros unicornis) Population in Nepal

Conservation of the Indian rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) in Nepal has a checkered past, but the country has become exemplary in its strategies to conserve this flagship species[1]. Once listed as endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, as of 2008, the status of the Indian Rhino is 'vulnerable' thanks for the conservation efforts[2]. A 2021 census revealed that population numbers are the highest they have been since the 1960s— from a mere 100 in 1966 to 752 in 2021[1]. The population health of the Indian rhinoceros tends to fluctuate in response to political turbulence and land use changes[3][4]. For example, the Nepali Civil War or agricultural expansion. Thus, this conservation success story is the result of a multi-faceted approach to reduce major anthropogenic threats, including poaching and habitat degradation[1][5]. By establishing national parks, namely Chitwan National Park, increasing patrolling, and focusing on community education and engagement, conservation strategists are able to involve various stakeholders to bring about positive change[6][2]. Future remediation should continue to engage various stakeholders, adopt landscape-based and multi-species conservation management strategies, and integrate more remote sensing technology[7][4] in order to reduce negative human-rhino interactions, manage invasive species, and improve social justice issues in communities moving forward[3][1][8].

Historical Context: The Protection, Loss and Use of Indian Rhinoceros in Nepal

In the 1950s Chitwan Valley, an area of the Terai valley, had around 1,000 Indian rhinoceros— but by the 1960s there were fewer than 100[9] [10]. During the Rana Regime (1846-1950), Indian rhinoceros were protected by the monarchy and only royalty were allowed to hunt them[11]. If anyone else did, it was punishable by death[11]. After 1950 the establishment of democracy and the eradication of Malaria opened up rhinoceros territory for settlement[9]. Prior to this only the Tharu indigenous lived in the Terai valley because they were the only people that could withstand malaria[11]. Increased human settlement in the Terai Valley led to habitat fragmentation and greater accessibility of rhinoceros hunting to poachers[9].

Indian Rhinoceros parts have been sought after in Nepal for generations[12]. Historically, their horns or skin were used to honour the dead, their skin was be made into jewelry, furniture and their hides were even used to create war shields[12]. But they were not hunted in mass amounts until after the 1950s[12].

In response to the dramatic decrease of Indian Rhinoceros populations, the Nepalese government turned the Rana Hunting Reserve into a sanctuary in 1954, and in 1958 the Wildlife Conservation Act made the Indian rhinoceros a nationally protected animal [9]. Then in 1959, to combat poaching the government created the Gainda Gasti patrol that was composed of 130 men who patrolled the Rapti Valley to prevent poaching [9]. However, the decrease in Indian Rhinoceros populations continued, and the Chitwan National Park was subsequently established in 1973 [9].

The establishment of the Park was a key milestone in conservation efforts, however the turbulent times did not stop there. In 1996, the Communist political party in Nepal declared a "People's War" on the Nepali state. A civil war had began that would rage on for a decade.[13] The regions where war insurgence began was in the Rukum and Rolpa Districts, which encompassed a significant Nepali State conservation territory, the Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve.[14] Later the rebels gained control of various conservation territories and national parks, including Chitwan National Park, as part of their strategy to take down the central government rule.[14] In order for these areas to provide refuge and revenue to the rebels over those 10 years, they drove off the staff employed by the government. In many parks, patrolling was suspended, leaving the wildlife unprotected and vulnerable.[14] [13] During this period, populations of Indian Rhinos suffered a dramatic decline under the lack of monitoring, and the levels of poaching increased greatly.[13]

When a stalemate was reached in 2005, and a peace accord was signed in 2006, the government worked to once again establish state authority in rural areas and in parks.[14] This led to the militarization of conservation efforts, including military training for rhino monitoring as part of a project launched in collaboration with WWF, the increasing role of Nepal's Army in conservation efforts, and increasing securitization in the buffer zones.[14][13] This increasing surveillance and law enforcement around rural areas and in the parts had large impacts in decreasing the poaching.[14]

Major Present Threats

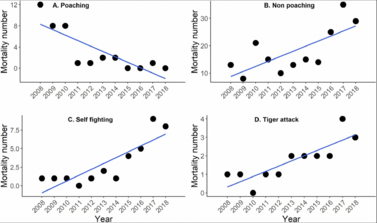

Recent data collected between 2008 and 2018 has shown that 80% of Indian Rhinoceros mortality in Nepal is due to intra-species self-fighting, poaching, tiger attacks, and "natural" causes[4]. These threats can primarily be attributed to habitat loss and fragmentation, risks from human-rhino interactions, and an increasing prevalence of invasive species[2] [7].

Habitat Loss and Consequences

Following the eradication of Malaria, agricultural expansion and encroachment into the rhino habitats, about 133,968 hectares of forest in the Tarai region were cleared during the1950s.[6] Fragmentation has also occurred when floodplains were transformed into croplands.[15] Leaving only pockets of small protected areas in its wake, this destruction and fragmentation of habitat has had far-reaching impacts[6]. For example, with loss of habitat, there is an increase of resource competition, self-fighting, and greater incidence of tiger predation due populations being pushed closer together, or with less options of escape with higher fragmentation.[7] With more fragmentation, also comes the risk of loss of genetic diversity within populations (due to the lack of genetic connectivity, inbreeding and the bottleneck effect - the decrease in the gene pool due to changes in the population).[7]

Poaching

Today, Indian Rhinoceros are still sought after by humans for the purpose of traditional medicines, trade and also for entertainment[6]. Although poaching is a major contributor of mortality of Indian rhinoceros populations, it has greatly decreased over the last decade due to ongoing patrolling and enforcement[4]. Poaching contributes to a loss of genetic diversity in Indian Rhinoceros populations, lowering biodiversity. This leads to overall ecosystem degradation because entire ecosystem functions are impeded with the decline in one species[6].

Human-rhino Interactions

Human-rhino interactions, any encounters or associations between people and rhinos that impact each either positively or negatively, have been on the rise as a result of land encroachment for agriculture or tourism[2]. Agricultural expansion has meant that farmlands provide an attractive source of food for the Indian Rhinoceros. This linked with the decreasing habitat area and native plant food sources leads to higher incidence of crops being raided by wildlife, including rhinos.[16] Often, this leads to greater incentive or poach the Indian Rhinoceros, and leads to acts of retaliation.[16] This reality is very clear in Chitwan National Park, where the density of wildlife is on the rise and the surrouding communities are experiencing economic loss.[16] Managing the complex dynamics of these interactions is a challenging one, and is one of the major threats towards wildlife conservation. As the number of visitors rises, there are increasing tourist demands, which puts pressure on Nepal's most biodiverse areas in terms of resource and land use, pollution, and pressure on the species themselves[2]. One study tracked the behavior change in Indian Rhinos exposed to tourism over time, and found tourism can impact their feeding patterns when visitors get closer than 12 meters and the rihnos are visited regularly.[17]. Increasing demand can increase the impact on behavioral patterns of the Rhinos[17]. In summary, human disturbance has put the health of the wildlife at risk[2]. Other more indirect anthropogenic pressures such as disease transmission take up a smaller share of the total deaths, however the extent of the threat of zoonisis through lifestock because of agricultural expansion is not entirely known since portion of deaths are due to unknown causes[2].

Invasive Species

The presence of invasive plants are another anthropogenic threat to Indian Rhinoceros.[18] In the Millennium Ecosystem Assessement they are listed as the second most dangerous threat following habitat fragmentation.[19] The invasive spieces in Chitwan Park are, the Mikania micrantha vine (the 'mile-a-minute' weed)[7], Chromolaena odorata and Mikania micarantah.[20] The vine currently covers 44% of Indian Rhinoceros habitat within Chitwan National Park and is notorious for its ability to grow over three inches daily[18]and outcompetes other plants for sunlight, nutrient and water.[21] It's rapid growth reduces the amount of land rhinoceros can graze from and suffocates native plants such as grasses and sapling trees that are normally eaten by rhinoceros.[22] Global heating due to climate change is expected to exacerbate[23], this situation. The loss of food due to Mikania Mircantah causes Indian Rhinoceros to look for sustenance from farmers field resulting in human-rhino interactions.[24] Chromolaena odorata grows in dryer zones compared to Mikania Micarantha.[20] Similair to mikania Micaranthat it inhibts the growth of native species but Mikania Micaranta is more dangerous[20]. Furthermore, between 2021-2022, ten rhinos were reported to have died due to drowning or getting stuck in swampy areas where they get entangled in invasive plant species[1]. The presence of the invasive plants, of course, feeds into other problems such as loss of resources, in particular for habitants of Chitwan National park's buffer zones.[25] With more habitat being overtaken and a decrease in the native plants that the rhinos depend on, resources are decreased leading to resource competition, rhinos self-fighting ,and human-wildlife conflict (as there has been an increased cases of rhinoceros consumption of human crops)[2].

Climate Change

Rhinoceros prefer a mosaic of grassland patches and the riverine forest on floodplains along the foothills of the Himalayas, where water remains available year round[26]. Currently available habitat is already becoming inadequate for Indian rhinoceros because of fragmentation, human expansion and encroachment, and invasive species; climate change is likely to decrease suitable habitat availability by bringing more flooding, extended droughts, and create more favorable growing conditions for invasive weeds[26]. All of these factors are a challenge for Indian rhinoceros conservation and are likely to stress the carrying capacity of current rhinoceros habitat[20].

Conservation efforts

Conservation efforts in Nepal have been in place for a very long time, with varying unsuccessful results. Increases in Indian Rhinoceros populations have been due to government involvement and community engagement, which have been most successful in recent decades.

Governmental Patrolling

Government law enforcement increases in patrol frequency and security posts have been shown to be the most effective methods of rhinoceros conservation and poaching prevention. One patrol a day from each of the 53 patrol units was shown to arrest 176 offenders and save rhinoceros from 2010-2015 [6]. Additionally, peaks of poaching were seen during 2002 (40 incidents) when there was a decrease in security posts, while poaching drastically lowered down to one or no incidents over the next 13 years as nearly 50 new security posts were established [6].

There has been a firm government commitment to punishments for poaching since the creation of the National Park and Wildlife Conservation Act in 1973, with a strict 500,000 - 1,500,000 rupee fine and/or 5-15 jail sentence possible for poachers and sellers of animal products [27] . During the years of 2011-2015, 2400 people were arrested [27]. As patrols currently cover more of the Chitwan National Park periphery and buffer zone areas, suggestions that patrolling should move further into the core park area with increased arming and community engagement have been made, as it may increase arrest rates [27]. Regardless, since 2007 sweeping operations in regions of high poaching risk have been conducted by the Army and park staff [6]. These tactics have been combined with the recent addition of real-time Android based SMART spatial monitoring and reporting systems. SMART systems have made it easier for patrol units to GPS collar and monitor specific Rhinos, and has made patrolling more accessible by making the recording of data easier[28]. Because of this, incidents of poaching have been shown to decrease while increased data has been collected [6].

Community Involvement

Conservation efforts have moved from more protective to participatory, involving local communities, and from a species only approach to a broader and all-encompassing landscape approach[27]. Community based engagement takes place through many means, including house-to-house visits, handing out pamphlets, and radio broadcasts, with the future possibility of less formal methods such as dedicating popular folk songs to conservation concepts[6]. The increase in poaching education in communities has led to the formation of many Community Based Anti-Poaching Units (CBAPU’s), rapid response teams for human-wildlife conflicts, and help in catching poachers[29]. Much of this has occurred through the education of youth about the importance of conservation through community instructors. As of 2017, over 500 CBAPU’s have been formed, and over 4,500 youth have been involved with CBAPU’s, poaching deterrence, and educational programs about Indian Rhinoceros conservation[29].

Further, 30-50% revenue sharing of protected areas to buffer zone communities has occurred, with funding going to income generation activities, skill-based training, veterinary services, and solar power fencing [29]. These investments have not only improved general human-wildlife relationships, but reduced human-rhino conflicts and deaths, leading to a 'win-win' situation for both parties[29]. All of these additions have greatly aided conservation efforts and highlight the Nepalese government’s transition to an increasingly participatory, landscape approach [27].

Transboundary Rhino Conservation in India and Nepal

The rhinos in Nepal will move between the India-Nepali border.[30] [29]Transboundary Conservation is when two countries collaborate to perform conservation.[31] Common paths they take are, Suklaphanta-Lagga Bagga - Pilibhit Forest, Dudhwa Tiger Reserve corridor, Bardia-Katerniaghat-Dudhwa and Basanta Forest corridor.[30] Moving between these areas makes rhinos more susceptible to threats; in 2013 one rhino was killed by a speeding train and one by poachers as they were moving between different locations,[30] thus transboundary conservation helps protect the rhino population in Nepal. Management plans between India and Nepal consist of improving the the corridors between the two countries utilizing initiatives such as community forestry projects.[3] With China, Nepal has developed transboundary conservation through signing the MoU where both countries agreed to suppress illegal wildlife trade and conduct and share research on Indian rhinoceros.[29] Nepal also holds meetings with India and China to discuss improvements towards transboundary conservation.[29]

Translocating

Translocating rhinoceros has also been a part of Nepal’s conservation strategy[32]. The population rebound in Chitwan National Park increased the likelihood of human-rhino conflict, so relocating individuals to other suitable areas of Nepal was beneficial[32]. Translocating also allows for rhinoceros populations as a whole to be less vulnerable to disease or natural disaster which may only impact one area, and, in this manner, translocation safeguards the genetic diversity of Indian rhinoceros[32].

Continued remediation and conclusion

Alongside continued community participation and education, notable efforts currently underway in Nepal to protect Indian Rhinoceros include approaching conservation through a socio-ecological lens to further resolve social justice issues tied to poaching and habitat loss[8]. Protected areas can be problematic for local communities if they are heavily dependent on them for subsistence and livelihood needs because they limit their access[30]. Thus, policy interventions which decrease community dependence on forest resources are needed to ensure long-term success[30]. Additionally, expanding educational and training opportunities is important; examples of policy measures include increasing agriculture income and generating off-farm employment opportunities so that locals can engage with conservation efforts and in careers which encroach on rhinoceros habitat less[30].

Multi-species conservation and landscape based management strategies that integrate more remote sensing technology are important components of Rhinoceros conservation as well[7][4]. Poaching prevention methods have been highly successful. A change that can still be implemented is that SMART patrolling should be combined with more patrol frequency instead of intensity.[6] [33]Modelling future climate scenarios, for example, can help researchers to predict how the growing impacts of climate change will influence Indian rhinoceros habitat.[34]

Adapting to impacts of global climate change, which exacerbates flooding, droughts, and encourages invasive plant growth[23] will be vital moving forward. Indian Rhinoceros are currently classified as "moderately vulnerable" to climate change, but ongoing monitoring and vulnerability assessments are needed in order to recommend adaptation measures for the species[34]. Under future climate and land use scenarios, Indian rhinoceros are expected to lose over a third of their current habitat[26]. Important future measures to mitigate climate and land-use induced changes include locating human development projects (for tourism, infastructure, etc) away from current and future suitable rhinoceros habitat; maintaining ponds rhinoceros rely on for temperature regulation; managing flood impacts; and expanding protected areas[26]. Futhermore, continued invasive species removal is important in keeping Mikania Micrantha growth at bay[28]. These efforts rely heavily on the education and participation of locals about how to most effectively remove invasive species[28]. Because local communities are on the frontline of the invasive species fight, it is imperative moving forward to increase community engagement by increasing their trust and relationships with NGOs, national parks, and other conservation organizations[28].

Thus, improving interagency coordination and transboundary cooperation are important steps in engaging and connecting more stakeholders, including local communities, government, NGOs, and National Parks within and outside of Nepal; this will increase communication, trust, and overall decrease the likelihood of poaching and illegal trade across borders of Indian Rhinoceros[27].

In addition to community involvement, species management, and increasing connectivity between stakeholders, a simpler but necessary component of Indian rhinoceros conservation is expanding protected areas[20]. Increasing Indian rhinoceros numbers is welcome news and a sign of conservation success, but also brings into question the carrying capacity of rhinoceros habitat in Chitwan and other national parks[20]. As rhinoceros populations rise, chances of self-fighting and rhino-human interactions increase as they need more space and food[20].

In conclusion, the ups and downs of Indian rhinoceros conservation in Nepal illustrates the power of communication and cohesiveness when it comes to conserving a species. Although there is still work to be done, especially in the face of climate change and growing anthropogenic impacts, evidence from ongoing Indian rhinoceros conservation in Nepal represents a glimmer of hope. Populations can recover if given the proper concern and management.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Pokharel, Gobinda (April 5, 2023). "As Nepal's rhino population increases, are threats being overlooked?". The Third Pole. Retrieved October 29, 2023.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Szydlowski, Michelle (November 2022). "Renegotiating citizenship: stories of young rhinos in Nepal". Journal of Ecotourism – via Taylor and Francis Onlin.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Thapa, Kanchan; Nepal, Santosh; Thapa, Gokarna; Bhatta, Shiv Raj; Wikramanayake, Eric (19 July 2013). "Past, present and future conservation of the greater one-horned rhinoceros Rhinoceros unicornis in Nepal". Oryx. 47: 345–351 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Bhandari, Shivish; Adhikari, Binaya; Baral, Kedar; Subedi, Suresh (October 2022). "Greater one-horned rhino (Rhinoceros unicornis) mortality patterns in Nepal". ScienceDirect. 38 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ↑ David Smith, James; Ahearn, Sean; McDougal, Charles (07 July 2008). "Landscape Analysis of Tiger Distribution and Habitat Quality in Nepal". Conservation Biology. 12: 1338–1346 – via Society for Conservation Biology. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 Mahatara, D.; Rayamajhi, S.; Khanal, G. (December 2018). "Impact of anti-poaching approaches for the success of Rhino conservation in Chitwan National Park, Nepal". Banko Janakari. 28 – via Nepal Journals Online.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Mukherjee, Tanoy; Sharma, Lalit Kumar; Saha, Goutam K.; Mukesh, Thakur; Kailash, Chandra (January 2020). "Past, Present and Future: Combining habitat suitability and future landcover simulation for long-term conservation management of Indian rhino". Scientific Reports – via National Library of Health.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Heinen, Joel; Shrestha, Suresh (22 Jan 2007). "Evolving policies for conservation: An Historical Profile of the Protected Area System of Nepal". Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. 49: 41–58 – via Taylor and Francis Online.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Thapa, Kanchan; Nepal, Santosh; Thapa, Gokarna; Bhatta, Shiv Raj; Wikramanayake, Eric (19 July 2013). "Past, present and future conservation of the greater one-horned rhinoceros Rhinoceros unicornis in Nepal". Oryx. 47: 345–351 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ UNESCO World Heritage Centre (November 2023). "Chitwan national park". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Roomakeer, Kees (2004). "Fragments on the history of the rhinoceros in Nepal" (PDF). Paychderm. 37: 73–78.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Martin, Esmond Bradley (24 April 2009). "Religion, royalty and rhino conservation in Nepal" (PDF). Oryx. 19: 11–16 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 "Past, present and future conservation of the greater one-horned rhinoceros Rhinoceros unicornis in Nepal". Cambridge University Press. 47: 345–351. 19 July 2013 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 Dongol, Yogesh; Neumann, Roderick (August 2019). "State making through conservation: The case of post-conflict Nepal". Political Geography. 85 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ↑ Vivek, Thapa (2015). [file:///Users/homeuser/Downloads/Analysis_of_the_one-horned_rhi.pdf "Analaysis of the One-Horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) Habitat in the Royal Chitwan National Park, Nepal"] Check

|url=value (help) (PDF). University of North Texas. - ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Lamichhane, Babu Ram; Persoon, Gerard (January 2019). "Contribution of Buffer Zone Programs to Reduce Human-Wildlife Impacts: the Case of the Chitwan National Park, Nepal". Springer Link. 47: 95–110.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Lott, Dale F; McCoy, Michael (March 1995). "Asian rhinos Rhinoceros unicornis on the run? Impact of tourist visits on one population". Biological Conservation. 73: Pages 23-26 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Murphy, Sean; Subedi, Naresh; Jnawali, Shant (2013). "Invasive mikania in Chitwan National Park, Nepal: the threat to the greater one-horned rhinoceros Rhinoceros unicornis and factors driving the invasion". Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International: 361–368 – via Cambridge.

- ↑ Kumar Rai, Rajesh; Scarborough, Helen; Subedi, Naresh; Lamichhane, Baburam (2012). "Invasive plants – Do they devastate or diversify rural livelihoods? Rural farmers' perception of three invasive plants in Nepal". Journal for Nature Conservation: 170–176.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 Bibhuti P., Lahkar; Bibhab, Kumar Talukdar; Pranjit, Sarma (2011). "Invasive species in grassland habitat: an ecological threat to the greater one-horned rhino (Rhinoceros unicornis)". Pachyderm: 33–39. Missing

|author3=(help) Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name ":16" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Nelson, Laura (2012). "Too Much Weed: Invasive Species in Chitwan National Park". Independent Study project (ISP) Collection: 1–15. line feed character in

|title=at position 43 (help) - ↑ Sean T, Murphy; Naresh, Subedi; Shant Rajn, Jnawali; Babu Ram, Lamichhane; Gopal Prasad, upadhyay; Richard, Kock; Rajan, Amin (2013). "Invasive mikania in Chitwan National Park, Nepal: the threat to the greater one-horned rhinoceros Rhinoceros unicornis and factors driving the invasion". Oryx: 361–368.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Vallangi, Neelima (24 Jan 2022). "Leading the charge: wildlife experts plan for future of Nepal's rhinos". The Guardian.

- ↑ Ortolani, Giovanni (2017). "Fighting a plant to save rhinos in Nepal". Mongabay: News & Inspiration from nature's frontline. Retrieved https://news.mongabay.com/2017/05/fighting-a-plant-to-save-rhinos-in-nepal/. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Rajesh Kumar, Rai; Scarborough, Helen; Subedi, Naresh; Baburam, Lamichhane (2012). "Invasive plants – Do they devastate or diversify rural livelihoods? Rural farmers' perception of three invasive plants in Nepal" (PDF). Journal for Nature Conservation: 170–176. line feed character in

|title=at position 83 (help) - ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Pant, Ganesh; Maraseni, Tek; Apan, Armando; Allen, Benjamin (07 December 2021). "Predicted declines in suitable habitat for greater one-horned rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) under future climate and land use change scenarios". Ecology and Evolution. 11: 18288–18304 – via Wiley Online Library. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 Ghimire, Pramod (May 2020). "Conservation Status of Greater One-horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) in Nepal: A Review of Current Efforts and Challenges". Grassroots Journal of Natural Resources: 1–14.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Ortolani, Giovanni (5 May 2017). "Fighting a plant to save rhinos in Nepal". Mongabay. Retrieved 14 Dec 2023.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 29.6 Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation (2017). "The Greater One Horned Rhinoceros Conservation Action Plan for Nepal (2017 -2021)" (PDF). Government of Nepal.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 Bibhab, Kumar Talukdar; Priya Sinha, Satya (2013). "Challenges and opportunities of transboundary rhino conservation in India and Nepa,". Pachyderm. 54: 45–51. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name ":17" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Basnet, Khadga (June 2003). Transboundary Biodiversity Conservation Initiative: An example from Nepal. Haworth Press. ISBN 1054-9811 Check

|isbn=value: length (help). - ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 "Successful rhino translocation in Nepal". WWF. 15 March 2002. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ↑ Linkie, Mathew; Deborah J, Martyr; Abishek, Harihar; Dian, Risdianto; Nugraha, Rudijanta T.; Maryati; Nigel, Leader-Williams; Wong, Wai-Ming. "Safeguarding Sumatran tigers: evaluatingeffectiveness of law enforcement patrols and localinformant networks". Journal of Applied Ecology.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Pant, Ganesh; Maraseni, Tek; Apan, Armando; Allen, Benjamin (29 June 2020). "Climate change vulnerability of Asia's most iconic megaherbivore: greater one-horned rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis)". Global Ecology and Conservation. 23 – via Science Direct.

| This conservation resource was created by Course:CONS200. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:1