Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/Quilombola communities in Vale do Ribeira São Paulo

Quilombola communities in Ribeira Valley, São Paulo, Brazil

This page discusses the case of a traditional Brazilian group called quilombolas, who are ethnical groups, essentially composed by rural or urban Afro-Brazilians, who define themselves according to their relation to land, ancestry, territory, bloodline, tradition and culture. The aim is to address land issues faced by quilombolas who inhabit the Ribeira Valley, a region in São Paulo, Brazil, and to discuss the allocation of power within the stakeholders involved in this case. This page also offers suggestions that could improve life quality of quilombola communities in Ribeira Valley.

Description

Explaining the origin of quilombos

Brazil is a country recognized for its interracial mixture. Since the European settlement in 1500s, different peoples, including Europeans, indigenous groups and Africans, were forced to share the same territory; beginning to build what we now know as Brazil.

Europeans wanted to exploit the multiple natural resources available in the new country. For that, they needed manpower, and the first peoples to do that work were Indigenous, who were replaced by the Africans in 1570 [1]. Until the end of the Slavery Period in 1888, about four million African slavers went to Brazil, with the majority being young men [1].

Slaves had no rights and were considered by the law as a ‘thing’ rather than a ‘person’. In the following century, unfairness and inequity led a few slaves to escape from the farms they worked in and look for freedom. The place where they took refuge in became known as quilombo. The person who inhabited the quilombo was called quilombola.

Moura`s work, as cited in Socio-Environmental Institute [2], describes that the word quilombo derives from quimbundo, an African term that means “society made up of young warriors belonging to ethnic groups uprooted from their communities”.

Hundreds of quilombos existed in Brazil, but the first one was home to Zumbi dos Palmares, considered until today a symbol of bravery by many people. In fact, the day of his death, November 20th 1695, is a holiday in most Brazilian cities since 2003 in respect for Afro-Brazilians and their history.

Defining quilombola communities: from colonial period to current days

According to the historian Boris Fausto (1996), quilombos were settlements in Brazil consisted of Africans who escaped slavery and established social norms similar to their homeland. It was a place where they could be free and manifest their culture, dance, religion and traditions.

Nowadays, quilombola communities, or territory originating from a quilombo community, are characterized as ethnical groups, essentially composed by rural or urban Afro-Brazilians, who were self-defined according to their relation to land, ancestry, territory, bloodline, tradition and culture [3].

Profile of the Quilombola communities in Ribeira Valley

Population characteristics

Ribeira Valley (from Portuguese, Vale do Ribeira) is located between two states: south-east of São Paulo and east of Paraná and has an area of 2,830,666 hectares (28,306 km2) distributed between 2,546 inhabitants [4]

By 1811, African and Afro-Brazilian slaves accounted for 23 percent of São Paulo’s population, a number that dropped to 19 percent in 1872 [5]. By 2008, the population of 411,500 habitants included quilombolas, indigenous peoples and smallholders [4], what explains its social and cultural diversity.

The population of Ribeira Valley is composed by young people, in which more than 60% are less than 30 years old [6], a pattern observed in most rural areas in Brazil. Another common trend is the lack of access to education; 42% of the population is illiterate [6]. The ones who went to school completed at most the 4th grade; rare are the cases in which a person had access to university, first because of the lack of financial investment in education in the communities and second due to the long distance between communities and universities [4].

Economic characteristics

73% of their earnings come from government grants [6]. 34% comes from the sale of crops [6], especially bananas, beans, cassavas and corn. Traditional handicrafts are also an important source of income [4].

The crops are cultivated by the families and are sold mainly inside the community and in the closest cities [4]. However, crop production allocated for commerce is decreasing, given the low price payed for the products and for the employees who take the products to the commercial centers, named atravessadores. Moreover, environmental laws that limit the opening of new agricultural areas also play a role in the decline of production [4].

Their relationship with the environment

In São Paulo state, Ribeira Valley is the region with the highest concentration of quilombos: out of the 21 communities found in the state, 15 are located in the Valley [4]. The region also has high environmental value since it contains the largest remnant of preserved Atlantic Forest in Brazil: out of the 7% of the remaining biome, 21% is located in the region [4].

Therefore, the communities from Ribeira Valley live harmoniously with nature. They use it for subsistence and for cultivation of their history; one that was handed down through decades, or even centuries.

Tenure arrangements

Ribeira Valley occupation history

The Valley was populated in the 16th century, when the settlers started exploring gold and other precious metals, bringing along Indigenous and African slaves [4]. Mining in São Paulo, as well as other primary activities developed in the state, were carried out on the backs of Africans slaves [5].

When gold exploitation was no longer booming and Africans/Afro-Brazilians were no longer slaves, agriculture started to be the main activity developed in the region for both subsistence and commerce. As a consequence, Africans and Afro-Brazilians who remained in the lands became small farmers, originating the quilombola communities in Ribeira Valley [4].

Therefore, some of the communities in the Valley have been occupying the same land for more than 300 years [4]. The Ivaporunduva community is an example. It was first occupied predominantly by African, African descendant fugitives and freed slaves [5]. Overtime, the inhabitants spread out and created neighboring communities [5].

Between 1950 and 1970, Ribeira Valley became a priority investment area. The government started to economically develop the region and to implement infrastructure projects, such as the opening of highways and roads. In the 1970s, the investment on the area was even greater due to tax incentives for cattle ranching and for banana and tea plantations, thus, taking more people to the region [5].

In the 1980s, social and environmental movements emerged in the Valley [5]. With the support of these movements and of groups from the Catholic Church through the Pastoral Land Commission (Comissão Pastoral da Terra), quilombolas started to organize themselves into associations [5], whose coordinators and directors are elected by the members of the associations every two years. Also, the members should participate on meetings and pay a monthly fee of 2.00 reais (approximately US$ 0.60) [4]. The aim of the associations was, and still is, to demand land titles and to expel non-quilombola farmers from the territories [5]. However, it was only in the 1990s that the process of land titling of quilombos began.

Therefore, the region has been occupied by quilombolas for centuries but their land right is still not well recognized. Most rural peoples who inhabit the Valley do not have the legal document that proves their ownership of the land [4].

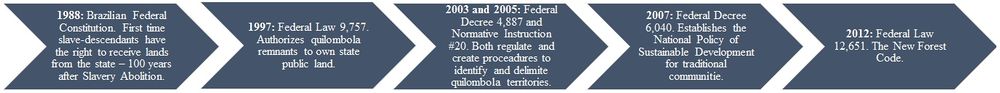

Fighting for recognition: the legal process for acquiring land title

Until today, Afro-Brazilians struggle for ethnical respect and racial equality [5]. Along with Indigenous peoples and supporters, they fight for land and identity recognitions. Every quilombola community in Brazil still have to claim for legal ownership of their land.

The process to acquire land title is described in the 2008 ISA Agenda. Quilombola communities must undergo bureaucratic procedures to have their land legally recognized; a process that involves a number of governmental organizations. The connection between government and community is done by the Associations. Each community has its own Association, which is the legal representative of the community.

In theory, a person or a community can define themselves as quilombola based on their history, tradition and culture inherited. Therefore, the legal process for land title starts with the acquisition of the ‘Self-Definition Certificate’. The Association, on behalf of the community, delivers a document, along with proofs (studies, photos, news), to the Palmares Cultural Foundation (Fundação Cultural Palmares) explaining why the community self-defines as quilombola. The president of the foundation will then issue and sign the certificate.

After that, begins the step of characterizing the community. It includes anthropological studies that evaluate environmental, economic, socio-cultural and spatial aspects of the land. This process is led by the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA), but also depends on other five governmental institutions. If all of them agree, the president of INCRA recognizes and announces the boundaries of the community`s territory. In the cases where the territory overlaps another public or private land, the government acts in accordance with each circumstance. One of the measurements is to declare eminent domain to the private lands.

Finally, the definitive land title is granted by INCRA and given to the Association. The title benefits the communities in different ways as an attempt to give them a better life and pay off for all the historical trouble done to slaves and slaves-descendant.

With the title, the community has full alienation rights to the land, but the way these rights work is different: the land cannot be used as mortgage, sold, split between members or used as loan by the communities nor by anyone. The land becomes property of the whole community to be used as a collective territory, where they can live and use it for their own good. With the title, the land is owned by the community as a group and can be passed down through generations.

Assessing land rights

Property rights at Ribeira Valley

According to the organization Quilombos do Ribeira, until 2011 there were around 2,500 quilombola communities in Brazil, out of which only 65 had acquired their land title since 1988. The organization averaged the emission of four land titles per year. In this case, it would take 625 years to give land title to all the communities, which would happen in the year 2631.

In Ribeira Valley, the majority of the quilombola communities do not have the documentation that verifies their ownership. According to the same organization, in 2015 only 6 communities had land title.

Land rights: the use of the land

In general, quilombola communities in Ribeira Valley have access to land rights regarding the use of the land. Even without the land title, quilombolas have access to land resources, they have the right to use and to sell products that come from nature and the right to manage the land. However, even with the land legally recognized, the management must fit into the federal environmental laws, which limits the communities' access to resources.

Therefore, the lack of property recognition and the fact that part of their land overlap public, private and/or unclaimed lands, makes it difficult to settle an accurate management plan. Also, the mix of ownership lead to conflicts between quilombolas and other inhabitants of the region [4].

Administrative arrangements

Describing administrative rights

Overall, quilombola communities in Ribeira Valley do not have administrative right regarding their territory. They do not have alienation rights and, due to the lack of ownership, they are not able to exclude others from using their land.

Most of the lands occupied and managed by the communities are either public or private property owned by people or organizations who do not live in them [4]. This means that the communities can have their land taken away from them at any time, depending on the owner's good will. In other words, quilombolas have no authority towards their lands, unless they undergo the process for acquiring land title.

Inside the families, there is a hierarchy to be followed. The family is divided into the family chief, normally the man, and the rest of the family. They all share day-to-day duties; some of the agricultural land is communal and used by all families in the community, where the men are responsible for the heavy activities, such as building the houses and the animals cage and extracting natural resources, and the women are responsible for other activities, such as seedling and gardening and taking care of household chores [4]. Those are some of the customary rules that, although not recognized in higher levels of authority, work well inside the communities.

As for the relationship between the communities and the outside world, the Associations are the responsible for this connection. The first Association in the Valley was created in 1994 as a response to the need of having a legal representative to facilitate the communication community-government. The Associations are the legal body that fight for the communities` rights [4].

The quilombola communities also rely on non-governmental organizations, institutions and activists to be heard by decision and policy makers.

A case study: dam constructions on Ribeira do Iguape river

The threat of dam constructions to generate hydropower is an example of the lack of administrative rights faced by quilombolas.

In 1970, the investment and improvement on infrastructure on the region attracted landowners, as they saw in Ribeira Valley the prospect of new lands [7], increasing the existing land tenure issues and the need to develop the region.

In 2006, there was the threat of building four dams along the Ribeira river, which would flood 60% of the areas inhabited by the quilombolas [7]. Until 2012, no dam construction on the main river was accomplished [8].

The non-accomplishment of the dam construction may be justified by social pressure and protests against it. However, the quilombola communities do not have the power to decide if it will happen or not. It may be just a matter of time until they find their communities submersed.

The fear of dam constructions, along with the lack of tenure recognition and the new environmental legislations, are the main issues faced by quilombola communities in Ribeira Valley [7].

Social actors

Affected Stakeholders

The affected stakeholders are the participants of this case study whose livelihoods are directly impacted by the actions taken in the region. They do not have decision making power, but they have procedural rights. In other words, decision makers consult them before taking action, but the affected stakeholders do not get the final say.

In Ribeira Valley, the affected stakeholders include:

- Community members, smallholders and indigenous groups who inhabit the lands in the Valley. They are the ones who are most affected by the territory conflicts. As it has been explained, they do not have power towards their land, unless if a land title is held. They are the ones who will actually feel the impacts of any action that is taken in the region.

- Associations – although they are the ones who make the connection between communities and government, the Associations do not get to decide if an action will happen or not. The Association, on behalf of the community that it represents, can participate on meetings and negotiations regarding quilombola territories, but they do not get the final say.

- Product buyers and business partners, encompassing atravessadores and sellers of quilombola products, generally located at the closest cities. They are the ones who participate on business processes. They are affected by the decisions taken by the interested stakeholders and their livelihoods also depend on those decisions.

Interested Stakeholders

Those are outsiders and are the people who actually have decision making power regarding quilombola lands in Ribeira Valley. Interested stakeholders include:

- Government: the government institutions are the ones that actually makes decisions and have the final say on what is going to happen in the communities. At the end of the day, they get the final say. Its power is diluted within different organizations and institutions, each one with its own relative power. Some of them are:

- The government of São Paulo

- The Federal government

- Governmental organizations involved in land tenure processes: INCRA, Palmares Cultural Foundation, Department of Natural Resources of São Paulo (DEPRN)

- Instituto Socioambiental (Socio-Environmental Institute, ISA) – ISA is a non-profitable social group that is respected by the Brazilian government and civil society. Their aim is to engage with minority groups in order to help them fight for their socio-environmental rights.

- Support groups, as activists, NGOs and the Catholic church – although these groups do not have the final say, they can influence decision making. They pressure decision makers and have persuasion power towards the government.

Discussion

The problem with the environmental legislation

Brazil's policies to protect the environment became stricter over time; thus limiting one's use of nature. In 2012, Brazil updated the Forest Code, which includes conservationist practices and Protected Areas designs that restricts everyone's access to land resources.

One content of the Forest Code is named Legal Reserve (RL), in which every rural property must have an area reserved for natural vegetation, where sustainable management and ecotourism can still be practiced. The size of the RL for the Atlantic Forest, where quilombolas of Ribeira Valley are located, the RL must be 20% of the territory.

For quilombola communities, the implementation of RL is only effected when the land is legally recognized [4]. Although the RL is only 1/5 of the total area, it is harmful for the communities` dynamics with the environment.

Also, the Forest Code defines Permanent Protection Area (APP), which are areas designed for ecological services maintenance – preserve water bodies, landscape, biodiversity, soil, ecological corridor –. The settlement of a APP inside a rural property must follow a set of rules that unable access to nature in those areas.

Another key instrument presented in the Forest Code is the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR), which is an online registration that must be done by all rural property owners in order to provide information about the land uses within each property. The owner must include the areas that are designated for APP and RL. The goal is to help the planning, organizing and monitoring of the properties in order to fight deforestation.

These three instruments are important for ensuring conservation practices within the country and is beneficial for the environment. However, they bring problems to the quilombola communities, since they are not suitable for the way that traditional groups live their lives [9].

In 2016, the organization Terra de Direitos (Land of Rights) heard a few people from traditional communities and put together their main difficulties regarding the new instruments. First, some of the communities are not able to access the system that allow them to register in CAR because of technical issues and also because some of them are illiterate.

Quilombolas stated on the organization`s report that CAR would facilitate the process of getting land title. ISA [10] helps them with the registration process, but even though their access to the system is limited.

In summary, traditional communities have lived in harmony with the environment for decades/centuries and have always done that in a way that is not harmful for the environment. However, new conservation policies shift the way they manage their land, what can be more unsustainable than allowing them to use the land the way they are used to.

Income diversification

Quilombolas reaction to conservation policies has been mainly two-fold: to resist some features of the law and press for concessions and to seek for other sources of income [5]. Quilombola communities won their right to shifting cultivation, a common agricultural practice for them, but they have changed habits to live with environmental rules prohibiting the use of fire and hunting [5]. The number of families that depend on shifting cultivation for their livelihoods has decreased due to environmental restrictions [5].

Therefore, the main challenge for the communities is whether they can maintain their ethno-racial identities and local livelihoods in a context of evolving environmental policies that endanger their traditional agriculture practices [5].

One way to increase revenue found by the quilombola communities in Ribeira Valley is described by Bowen (2017) as the Quilombola Circuit, a community-based ethno-ecotourism enterprise. ISA sponsored the first project in one of the communities, Quilombo Ivaporunduva, which provided jobs for community members - since 2010, the tourism business has employed 35 residents of Ivaporunduva. In a typical season, Quilombo Ivaporunduva hosts 100 visits.

Another way to increase income is to diversify the crops that are grown in the communities, which is being done since 2001 with the help of projects sponsored by ISA [5]. Project examples are: increase production of commercial and organic banana; manufacture banana chips and others dried banana products; restock seedlings and seeds of traditional native species that are important for both commercial and livelihood purposes. The seedlings and seed produced can be traded in annual seed fairs.

Moreover, they can seek legal genetic heritage protection of those species and avoid their extinction. This is important for the community and for the environment because many of the varieties were at risk, as fewer farmers were cultivating them because of the enforced shifting cultivation regulations [5].

Handicrafts is also an activity that has always been developed in the communities, specially by women. ISA has helped those women to expand their handicrafts businesses.

Successes and failures of projects

As it has been shown, ISA develops projects within Ribeira Valley as an attempt to meet the demands of the quilombola communities. Most projects include income diversification and the fight for legal rights. With the help from ISA, community members are able to connect with the outside world and develop activities that are most suitable for their reality.

As for the Quilombola Circuit, quilombola themselves observe benefits and failures in the project. They evaluated the ethno-ecotourism project as economically beneficial for the community. However, they acknowledged concerns as income inequality, loss of culture, disease, prostitution, drugs, and problems of sanitation and garbage [5]. All these problems may increase as the Quilombola Circuit evolves.

The increase in handicraft businesses is a positive consequence for both environment and community. The raw materials used by the artists would have no monetary value if it wasn’t for handcrafting. Some materials they use include leaves, seeds and vines from a diverse range of crops grown in their land.

The problems with the environmental legislation are many. Quilombolas interact with the land according to cultural and traditional practices [5]. Communities that already have limited decision making power, have even less ability to decide on the use of their land with the enforcement of the legislation. In a way, environmental conservation policies have threatened quilombolas livelihood and their ethno-racial identity [5].

It would be beneficial for the quilombolas if the laws respected their historical relation to the land when enforcing it. That would also be good for achieving the conservationist goals of the legislation, since the communities have shown to respect and preserve nature.

Critical issues within the communities

In general, most issues faced by communities from Ribeira Valley are related to the lack of land and identity recognitions. The process they undergo in order to be legally recognized and acquire their land title is long and bureaucratic. The law states that a community can be self-defined as quilombola. However, it needs to provide a set of proofs in order to be legally recognized and to have their land legally recognized, a process that depend on several governmental institutions. In that matter, who actually defines a person or a community as quilombola is not themselves.

The Associations play an important role in that sense. They are responsible for connecting community and government and can take the issues raised by their members to whom actually has the power to solve them. Although they are not always heard, the Associations are important to pressure the government and to make quilombolas be noticed.

Another critical problem faced by the communities relate to the lack of basic sanitation. Not all families have access to electricity. Until 2008, no community had access to clean water nor treated sewage. Most of the times, the family members themselves install pipes in order to access water in their homes, water which comes from nearby rivers [4]. Most of the families burn their wastes and the organic waste is used to feed the animals [4].

The families` access to health and education systems is also limited. Rare are the communities that have health centers and, when they do, the centers lack professionals, medicines and even a proper place to conduct the treatments [4].

If the government drove policies to mitigate these issues, it would bring social and environmental benefits to those communities who are marginalized and excluded from society.

Assessment: discussing power

So far, it should be clear that quilombolas have no decision making power compared to the government. Corruption is one of the main causes of this issue in Brazil. Sometimes decision makers know the right thing to do, but the system is so corrupt that they are not able to pass through it. Bribery and threats are constant approaches that keep people in track.

Corruption is a problem worldwide that blocks the operation of many actions that would be extremely beneficial for society. A case study in Senegal [11], for example, shows how power was distributed when the Forestry Code of 1998 transferred to elected rural council the right to control and allocate forest access. The case study describes the Rural Council President, who tries not be persuaded into illegality in an attempt to protect his community`s rights. The illegality would benefit people in higher levels of hierarchy. However, in the end he is bribed and dragged into it.

Another factor that contributes to power inequity regards the standards in which society is built in. Sometimes, the weak side – in this case study, the quilombola communities – don`t even know they are being deceived. This happens because they are subjected to a set of social actions and beliefs that, although not fair, rule the way society behaves. It is a kind of violence named structural violence, in which power is distributed in an unfair way due to some beliefs that are embedded in society and that do not allow the weak side to see the unfairness.

This relation is also explained by John Gaventa, a political sociologist who analyses the relation of power in his theory Three Dimensions of Power, by Johan Galtung and many other scientists who study power distribution within the society.

Therefore, decision making power is not equal between the different hierarchy levels and, for this case study, quilombolas are the ones who lose. A numbers of factors drive this inequity and control the way society functions.

Recommendations

Existing government projects

The existing programs work well and allow traditional communities to access market and should be expanded and improved in order to engage more communities. Some of them include:

- Microfinance –smallholders can apply for a financing program named PRONAF (National Program for the Improvement of Family Agriculture). PRONAF money can be invested in technology and machineries, agro-industrial activities or crop costing, depending on the farmer`s need [12]. PRONAF provides credit for Quilombola communities in Ribeira Valley so they can produce perennial crops, such as banana, passion fruit and pupunha, a local palm tree species [4].

- Food Acquisition Program (PAA) – is part of the National Food Supply Company (CONAB), which guarantee to direct purchase part of the crops produced [5] as an attempt to strengthen local production.

- Technical Assistance and Rural Extension (ATER) – a law in force since 2010 that provides technical services to traditional communities [13].

- Joint Forest Management (JFM) – taking as an example the case of West Bengal, in India, who were pioneers in JFM, this approach also works for the quilombolas in Ribeira Valley. JFM includes the partnership of governmental forest departments with local communities. However, in both case studies, the communities still not have decision-making power.

Improvements to be made

The programs established by the government benefit the communities but do not make-up for the low bargaining power that they have [5]. Different improvements could be made to increase quilombolas' power and influence within the decision-making processes.

The most important improvement to be made is devolution, which means to give power and rights to communities in a local level [14]. Besides devolution, decentralization of power would also help quilombolas, meaning that high-level authorities would give decision-making power to lower levels of government [14].

Integrated Land Use Planning (ILUP) would also help to devolute and decentralize power. ILUP aims to bring together different stakeholders to decide on land use and on the use of its resources in order to maintain the cultural, social, environmental and economic values of a specific area. ILUP would increase quilombolas decision-making power [15].

Also, leaders should listen to the communities before making conservation plans and even threat traditional communities as a separate case. In fact, quilombola communities have shown to be successful in conserving the Atlantic Forest: out of the 7% of the remaining biome, 21% are located in the Valley [4]. Considering the conservation existent in the area, Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) could also increase local income.

Another idea would be to enhance the connection between the communities and close universities and schools. Together, these institutions could develop projects and experiments within the communities, such as agroforestry and seedling production of native species. This would yield benefits for the community members, the university/school students and the environment.

However, all these improvements can only be made when the problem of corruption is solved. For that, social groups and activists are important when pressuring the government and play their role as citizens in order to fight for a fairer world.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Fausto, B. (1996). A escravidão - índios e negros. In História do Brasil (pp. 28–31). São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo.

- ↑ Instituto Socioambiental. (n.d.). Territories of descendants of quilombos. Retrieved November 5, 2017, from https://uc.socioambiental.org/en/territórios-de-ocupação-tradicional/territories-of-descendants-of-quilombos

- ↑ Brazilian Ministry of Agrarian Development. (2005). Comunidades Quilombolas. Retrieved November 18, 2017, from http://sistemas.mda.gov.br/aegre/index.php?sccid=579

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 Instituto Socioambiental. (2008). Agenda Socioambiental de Comunidades Quilombolas do Vale do Ribeira. (K. M. P. dos Santos & N. Tatto, Eds.). São Paulo: ISA.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 Bowen, M. L. (2017). Who owns paradise? Afro-Brazilians and ethnic tourism in Brazil’s quilombos. African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal, 10(2), 179–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/17528631.2016.1189689

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Júnior, N. N. P., Murrieta, R. S. S., Taqueda, C. S., Navazinas, N. D., Ruivo, A. P., Bernardo, D. V., & Neves, W. A. (2008). The house and the garden: socio-economy, demography and agriculture in Quilombola populations of the Ribeira Valley, São Paulo, Brazil. Boletim Do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Ciências Humanas, 3(2), 227–252. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1981-81222008000200007

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Carvalho, M. C. P. de. (2006). Bairros negros do Vale do Ribeira: do “escravo” ao “Quilombo.” Universidade Estadual de Campinas.

- ↑ Sevá Filho, A. O., & Kalinowski, L. M. (2012). Transposição e hidrelétricas: o desconhecido Vale do Ribeira (PR-SP). Estudos Avançados, 26(74), 269–286. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-40142012000100019

- ↑ Martins, P., Barbosa, B., Porto, D., & Schamm, F. P. (2016). Cadastro Ambiental Rural para a agricultura familiar: Experiências e dificuldades.

- ↑ Instituto Socioambiental. (2016). Quilombolas discutem Cadastro Ambiental Rural (CAR) em seus territórios. Retrieved December 2, 2017, from https://www.socioambiental.org/pt-br/noticias-socioambientais/quilombolas-discutem-cadastro-ambiental-rural-car-em-seus-territorios

- ↑ Ribot, J. C. (2009). Authority over forests: Empowerment and subordination in Senegal’s democratic decentralization. Development and Change, 40(1), 105–129.

- ↑ Brazilian Ministry of Agrarian Development. (2017). Como funciona o Pronaf? Retrieved December 3, 2017, from http://www.mda.gov.br/sitemda/secretaria/saf-creditorural/como-funciona-o-pronaf

- ↑ Brazilian Ministry of Agrarian Development. (2015). Assistência Técnica e Extensão Rural. Retrieved December 3, 2017, from http://www.mda.gov.br/sitemda/noticias/assistência-técnica-e-extensão-rural

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Bulkan, J. (2017). Joint Forest Management (JFM) in West Bengal - 2. Vancouver.

- ↑ Sustainable Forest Management in Canada. (2017). Canada’s Integrated Land-Use Planning. Retrieved December 3, 2017, from https://www.sfmcanada.org/en/forests-and-people/integrated-land-use-planning

| This conservation resource was created by Renata Moura da Veiga. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |