Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/2023/Monteverde Cloud Forest, Puntarenas, Costa Rica: A hotspot of co-production of knowledge and conservation?

Summary of Case Study

Costa Rica hosts numerous unique ecosystems that support an array of biodiversity. Among these ecosystems is the tropical montane cloud forest in Monteverde, Costa Rica. This ecologically significant area receives immense attention from the scientific community, which leads to synergies between various stakeholders. The collaboration between actors results in considerable contributions to the literature on rare biodiversity, cloud forest ecology and tropical ecosystems and climate change. This review assesses the stakeholders involved in the Monteverde region, the role of conservation and research, and Monteverde as a successful model for a site of co-production of knowledge.

Keywords

Monteverde; Eco-tourism; Collective Conservation; Cloud Forest; Collaborative Research; Costa Rica

Positionality Statement

Before one engages in this case study, it is important to know that this work was completed on the Traditional, Unceded Territory of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) First Nation, British Columbia, Canada.

Understanding a portion of my past is crucial in reading this case study and in understanding the basis of my opinions. I was born and raised in Salmon Arm, British Columbia. This small town is found in Southern Interior B.C; in the area, the community has strong ties to the surrounding forest ecosystem. Thus, growing up in this community, I always had an affinity towards the forest and surrounding environment. This connection to our environment led me to pursue an undergraduate degree in Environmental Science and Biology at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. This experience expanded my knowledge on the inextricable connection between our environment and our society. This acquired knowledge and my pre-existing passion for forestry led me to enrol in the Master of International Forestry program at The University of British Columbia. To date, my education shapes the way in which I view the world, which inevitably influences the direction of this case study.

Aside from my upbringing and my academic past, my experience in Monteverde plays an integral role in my positionality regarding this case study. My time spent in Monteverde preceded my bachelors degree. At that time, I wasn't nearly as knowledgeable on the importance of conservation and research in ecologically important areas like Monteverde. However, given my connection to the environment, and an appreciation for conservation, Monteverde was beyond impressive. Recalling my visit to the area with my new knowledge and philosophy, I can truly appreciate the role that Monteverde plays in the realm of research and conservation.

Introduction

Monteverde is a small mountainside community that is located in Puntarenas, Costa Rica[1]. More specifically, it is found in the northwestern region of Puntarenas, within the Cordillera de Tilarán Mountain range; which is situated along the continental divide[2]. With its unique location along the continental divide, the tropical montane cloud forest ecosystem (TMCF) is influenced by both the Caribbean and Pacific slope– creating distinct ecological conditions[3]. The threatened TMCF presents a rare ecological setting that fosters high levels of endemism and an array of flora and fauna species [2] [4][3].

Within Monteverde, there are three primary seasons– the rainy season, windy-misty season, and the dry season. The rainy season extends from May to November; during this span of seven months, there is roughly 2500mm of precipitation– the largest volume of precipitation is during the latter three months of the rainy season[5]. From the end of November to the beginning of January, is the windy-mist season; it is during this period that the trade winds develop and bring moisture from the Caribbean Sea to the mountains. The last season is the dry season that spans from January until April; during this season, water sources begin to deplete[6].

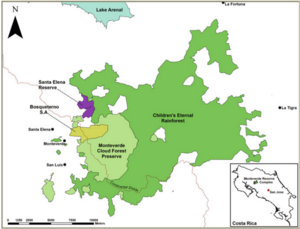

Monteverde itself is a small community with a population of roughly 1,000 people[3]; however, it belongs to the greater Monteverde canton– a regional municipality that includes Cerro Plano, Cañitas, San Luis, Santa Elena, and La Lindora[3]. This canton has a population of roughly 4,500, where Santa Elena is the largest town. Within this region, there are several forest reserves that were created to conserve the cloud forest ecosystem; this set of reserves is referred to as the Monteverde Reserve Complex[3], and consists of four main reserves: the Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve, the Bosqueterno S.A, the Children's Eternal Rainforest, and the Santa Elena Cloud Forest Reserve [7]. This grouping of reserves accounts for 27,000 hectares of protected land and is a part of a larger federal conservation area, the Arenal-Tempisque Conservation Zone[7].

Within the Monteverde Reserve Complex, there is an emphasis on conservation, education, research, and sustainable community development[3]. To obtain these goals, Monteverde has developed international connections to academic institutions, governmental organizations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs)[4]; all while improving local capacity and ensuring community involvement.

The Tropical Montane Cloud Forest Ecosystem

Description of the Ecosystem

The majority of the Monteverde region is categorized as a tropical montane cloud forest (TMCF), which is considered to be one of the most threatened ecosystems in the world[3][4]. Throughout the Monteverde TMCF, there are several defining characteristics of this ecosystem including that it is found at higher elevations (800m-3500m), and has a consistent low lying fog/cloud that condenses on the canopy and vegetation to facilitate the process of horizontal precipitation– which is responsible for approximately 45% of the precipitation throughout the continental divide[8] [9]. The continuous moisture delivered from the clouds is vital in the TMCF ecosystem; this water input has "implications to vegetation characteristics, vegetation productivity, nutrient uptake, soil and litter composition, and a positive water balance"[9]. Horizontal precipitation is particularly important during the dry season when water inputs decline[8]. As the the water input plays an integral role in the TMCF ecosystem, any change in climate has cascading impacts on the entire ecosystem [9].

Within the Monteverde TMCF, there are seven unique life zones (micro climates) that result from changes in elevation, and orientation (Caribbean facing slope versus Pacific facing slope) [4]. Life zones categorize climatic regions based on several shared characteristics, such as annual precipitation, evapotranspiration, average temperature, and flora and fauna found throughout the zone[6]. Categorizing different life zones is important for understanding ecosystem function, resiliency, and biodiversity[3].

| Life Zone | Elevation

(m) |

Annual Rainfall

(mm) |

Dry Season Duration

(months) |

Canopy Height

(m) |

Life Zone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Premontane Moist Forest | 700-1300 | 2000-2500 | 5.5 | 25 | 1 |

| Premontane Wet Forest | 1300-1500 | 2500-3500 | 5 | 30-40 | 2 |

| Lower Montane Wet Forest | 1500-1650 | 3000-5000 | 3 | 25-35 | 3 |

| Lower Montane Rain Forest | 1650-1850 | 5000-8000 | 2 | 20-30 | 4 |

| Premontane Rain Forest | 700-1600 | 4000-7000 | 1 | 30-40 | 5 |

| Tropical Wet Forest | 500-700 | 3500-4500 | 1 | 30-50 | 6 |

| Tropical Moist Forest | 600-900 | 3500-5000 | 1-2 | 30-50 | 7 |

Biodiversity

The multitude of life zones in Monteverde enables significant levels of biodiversity to persist in the region [3]. Across different life zones, are numerous ecosystems that provide habitats for various endemic species of flora and fauna– making Monteverde an epicenter for rare biodiversity[10]. Within the Monteverde Reserve Complex, more than 3,000 species of flora have been identified, and among these identified species, nearly 10% are endemic to the Tilarán Mountains [6]. Additionally, the region hosts "425 species of birds, 120 species of mammals, 60 species of amphibians and 101 species of reptiles"[6]. Between the flora and fauna, the Monteverde TMCF is home to nearly half of the country's species and 2.5% of the worlds biodiversity[6]. Amongst these species, many are at risk, which has fostered numerous conservation measures and projects within the Monteverde Conservation Reserve Complex. A species that has received considerable attention and projects dedicated towards its survival, is the Three-wattled Bellbird (Procnias tricarunculatus)[7]. The Three-wattled Bellbird is listed as vulnerable under the IUCN Red List [11]. To ensure habitat connectivity, the Bellbird Biological Corridor project aims to connect Monteverde to the Gulf of Nicoya (on the Pacific coast), by creating ecological networks and habitat corridors[12].

Historically, it was the endemic species of Monteverde's TMCF that caught the initial attention of researchers[13]. Several species, including the Resplendent Quetzal (Pharomachrus mocinno) and the Golden Toad (Incilius periglenes) were of particular interest[7][4]. Economically, the Resplendent Quetzal is the most important species to the Monteverde region[3]; its unique plumage attracts birders from across the world, bolstering the eco-tourism industry. In the past, significant amounts of researchers came into Monteverde to study the Golden Toad[13]. This species was endemic to the Monteverde's TMCF; however, a combination of climate change altering its habitat, and chytrid, a fungal disease, led to it becoming officially extinct per the IUCN Red List in 2004[14].

Although in many cases species haven't gone extinct, many species populations are continuing to decline. Through effective conservation and restoration of habitats, it is possible to prevent Monteverde's endemic species from going extinct.

Threats to Monteverde's Tropical Montane Cloud Forest

Climate Change

Climate change is the primary threat to the Monteverde TMCF. Although climate change has a multitude of impacts, the prominent threat to the TMCF is the average change in temperature; resulting in more consecutive dry days[3]. The increase in days that don't receive precipitation will have dire impacts on ecosystem function– the reduced moisture in the environment will alter habitats, putting species that depend on the moisture in the TMCF at risk[7].

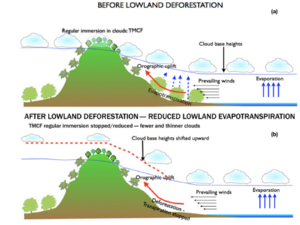

Alteration of Land Use

In the lowlands that surround the Monteverde region, farming is a common practice. There is concern that farming practices could expand throughout the lowland and into the Premontane forest on the Caribbean slope[4] [8]. The conversion of lowland and Premontane forest is extremely problematic. With this change in land use, is a change in surface temperature and reduced rate of evapotranspiration; which play a critical role in the formation of clouds[8]. Clouds having less moisture leads to elevated cloud height, and reduced cloud immersion[4]. This is particularly concerning for the dry season when there is already an increase in water stress[8].

History

Prior to the establishment of current day Monteverde, the landscape took a different shape. In the past, the dominant land use at the base of the mountain was small scale subsistence farming. The local farmers known as the "Ticos" were the only people in the area[15]. This was until the beginning of the 1900's, when settlers fled to the Monteverde region for gold in rivers[13]. After this "rush" ended, settlers remained in the area where they practiced farming alongside the Ticos. This was done by the settlers to satisfy the tenure laws that declared squatters could obtain legal title to the land if they improve the land in some capacity over a ten year period[13][16].

In 1951, a group of settlers from the United States known as the Quakers, migrated to the Monteverde region; the group of 41 people purchased roughly 1,200 hectares from the Guacimal Land Company[13][15]. Like the Ticos and other settlers, the Quakers began farming; however, they primarily practiced dairy farming. Through their successful dairy farming, the Quakers built a dairy processing plant; with its growth, local farmers began to sell their dairy products to the processing plant[4]. The revenue generated by the cheese production enabled the community to improve and add infrastructure. Ultimately, the production of cheese played an integral part in the economic development of the Monteverde region[13][17].

Within the 1,200 hectares that the Quakers owned, they designated approximately one third of the land in the higher elevation to remain untouched[17]. The preservation of the forest land was done to protect the watershed and ensure the water they relied on would remain uncontaminated. Amongst the Quakers, a community group, Bosqueterno S.A, was formed with the aim of determining the use of the land in the future[13].

During this period of development in the Monteverde region, researchers began to enter the area to study the endemic species of the TMCF. Among these researchers was George Powell, who purchased land in the region in 1970[13]. Powell then contacted the Tropical Science Center (a non-profit organization based in San Pedro de Montes de Oca) to manage this land, leading to the establishment of the Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve (MCFR) in 1972[13]. Not long after the establishment of the MCFR, the Bosqueterno S.A, entered into an agreement to lease the protected watershed land to the Tropical Science Center; which would be protected as a part of the MCFR. This was the beginning of the Monteverde Reserve Complex.

Tenure arrangements

History of Property Rights

Property rights in Costa Rica adhere to Civil Law rather than English Common Law. Within Civil Law, there is Prescriptive Rights and Adverse Property Possession[18]; which can be commonly referred to as "squatter's rights". In 1855, the Costa Rican Government, legally recognized possessory/ squatters' rights [19]; squatters were given additional rights in 1941, through the Ley de Informaciones Posesorias, Ley No. 139[19]. The passing of this law meant that "squatters can gain possessory rights to private lands after making improvements to the land and after one year of continuous, public, peaceful and good faith occupation"[19]; these possessory rights can transition into ownership rights over the span of ten years[19] [18].

Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve

The Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve (MCFR) is on private land that is owned by the Tropical Science Center (TSC)[3]. Until 1970, this land in Monteverde was occupied by squatters that had possessory rights on government land [16][13]. This was until 1970, when the government-owned land was bought by a researcher known as George Powell[13]. Powell then sold this land to the TSC, creating the Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve; since then, it has increased substantially in size and now consumes 4,125 hectares in the Monteverde region[4].

Children's Eternal Rainforest

The Children's Eternal Rainforest (CER) is located on private land that is owned by the Monteverde Conservation League (MCL)[3]. The MCL was created in 1986 by a group of local residents; initially, the aim was to obtain land for conservation purposes. The funding to acquire this land was raised from donations by children and organizations around the world[20]. To date, the CER is the largest private reserve in Costa Rica (23,000 hectares)[20].

Bosqueterno S.A

The Bosqueterno S.A (BESA) is a corporation that was created by the Quaker family in 1972[21], and owns 554 hectares of watershed within the Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve[7]. This area is leased to the TSC, and is protected through the Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve[7]. This lease began in 1974 and has a price of one colon per year[21]. Within this lease there are several regulations prohibiting actions of the TSC.

- "Fell, chop or trim any trees or plants;

- Take out any kind of products of the natural forest;

- Practice any kind of hunting or remove any kind of living specimen of wild animal life;

- Introduce new species of flora or fauna without a former agreement between both parties;

- To build houses, buildings, or installations except those necessary for protection and administration;

- To build roads or introduce any kind of motorized vehicle within the property except what may be necessary for protection and administration"[21].

Santa Elena Cloud Forest Reserve

The Santa Elena Cloud Forest Reserve (SECFR) is owned by the state and leased to the Colegio Técnico Profesional de Santa Elena (CTPSE), a high school in the town of Santa Elena [3]. The lease between the SECFR and the ACAT-MINAE (conservation area that is a part of SINAC) is a long term lease (no specified date) that is renewed every five years[4]. The SECFR was established in 1992, and is managed by administrative board of the CTPSE and the community of Santa Elana[3].

| Rights | Monteverde Cloud Forest | Children's Eternal Forest | Santa Elena Cloud Forest | Bosqueterno S.A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access | Is mediated by the landowner; however, access regulated and often prohibited in the whole protection areas[22] | Is mediated by the landowner; however, access regulated and often prohibited in the whole protection areas[22] | Access regulated and often prohibited in the whole protection areas, except in particular public use zones where regulated activities are allowed according to management plan[22] | Is mediated by the landowner; however, access regulated and often prohibited in the whole protection areas[22] |

| Withdrawl | Withdrawal is prohibited[22] | Withdrawal is prohibited[22] | Withdrawal is prohibited[23] | Withdrawal is prohibited[21] |

| Exlcusion | Yes | Yes | Yes, controlled by SINAC[22] | Yes |

| Management | Yes | Yes | The Administrative Board of the CTPSE manages the forest reserve[7] | Yes |

| Alienation | Private owners can sell or lease their land, forest and carbon rights to other parties[22] | Private owners can sell or lease their land, forest and carbon rights to other parties[22] | No, the land is owned by the state (SINAC)[23] | BESA would hold the power in determining alienation rights–TSC cannot sell or lease the land[21] |

| Duration | No timeline– it is owned and managed by the TSC[4] | No timeline– it is owned and managed by the MCL[4] | Lease between the CTPSE and the federal government, signs lease every 5 years with the ACAT-MINAE (part of the SINAC)[4][7] | There is a 90 year lease agreement between BESA (the owner) and the TSC (manages the land). The lease began in 1974 and is renewed every 5 years[3] |

| Bequeath | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Extinguishability | Yes, the state can legally expropriate or compensate[23] | Yes, the state can legally expropriate or compensate[23] | Yes, the state can legally expropriate or compensate[23] | Yes, the state can legally expropriate or compensate[23] |

Decoded Acronyms:

ACAT-MINAE: Arenal-Tempisque Conservation Area and the Ministry of the Environment and Energy

BESA: Bosqueterno S.A

CTPSE: Colegio Técnico Profesional de Santa Elena

MCL: Monteverde Conservation League

SINAC: National System of Conservation Areas

TSC: Tropical Science Center

Institutional/Administrative arrangements

Apart from the SECFR, the forest reserves in the Monteverde Reserve Complex are owned by private organizations. Regardless that these reserves are privately owned and managed, they are still federally protected through the Arenal-Tempisque Conservation Area (ACAT)[24]. The ACAT is a part of a national conservation system known as SINAC, which encompasses various designations of conserved areas, including forest reserves[24]. All forms of conserved areas are overseen by the Minister of Environment[24].

This conservation system fosters decentralized management of forest reserves while providing SINAC with legislative authority through the Biodiversity Law [23]. The SINAC is involved in providing technical support for the organizations who manage the forest reserves. Additionally, they are involved at the local level to facilitate cohesion between actors, and to ensure sustainable project management[24]. By engaging with the local organizations and supporting them in their management, SINAC can further ensure that the local management of the forest reserves coincides with larger conservation projects. An example being to facilitate the Bellbird Biological Corridor that passes through multiple reserves, thus involving multiple actors; the SINAC is able to ensure that these reserves individual management is effectively contributing to the project.

Stakeholders

| Forest Reserves | Non-Governmental Organizations | Community | Academic Institution | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monteverde Cloud Forset Reserve | Tropical Science Center (TSC) | Monteverde Community | Monteverde Institute (MVI) | Canton (Municipal) |

| Children's Eternal Rainforest | Monteverde Conservation League (MCL) | Santa Elena Community | University of Georgia, Costa Rica (UGACR) | Provincial |

| Santa Elena Cloud Forest Reserve | Costa Rican Conservation Foundation (CRFC) | Cerro Plano | Texas A&M Soltis Center (TAMU-Soltis) | Federal |

| Bosqueterno S.A | ProNativas-Monteverde | Cañitas | Costa Rica National University (UNA) | |

| Monteverde Community Fund | San Luis & La Lindora | Colegio Técnico Profesional de Santa Elena (CTPSE) |

Forest Reserves

Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve, Bosqueterno S.A, Children's Eternal Rainforest, and the Santa Elena Cloud Forest

Only the main four forest reserves were listed in table 3; all of these forest reserves are affected stakeholders– the decisions made in this area will have cascading impacts on this actor. The forest reserves have multiple roles; to conserve the forest ecosystem and the flora and fauna within its boundaries; foster education and research; support the local economy through sustainable ecotourism; provide ecological services to the communities in the Monteverde region. In the case of the MCFR, CER, and BESA, they are privately owned; their founding organizations hold the power in these reserve lands. However, for the SECFR, the SINAC holds the ultimate power– the CTPSE manages the SECFR but the land is state owned.

Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs):

Tropical Science Center (TSC)– Affected Stakeholder

Only the main NGOs in the Monteverde region were listed in table 3– there are many more than the listed NGO's in the Monteverde region. The TSC, is a non-profit organization that was established in 1962 and is based out of San Pedro de Montes de Oca[25]. To date, the TSC plays a prominent role in Monteverde; it is the owner of the Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve, and manages the Bosqueterno S.A forest reserve through a lease agreement with BESA[21]. As the owning and managing organization, the TSC has been effective in acquiring and trading land with other reserves; the trade and acquisition of land plays a vital role in creating habitat corridors between reserves and other protected areas– such as the Bellbird Biological Corridor [7]. Without the collaboration between early researchers and TSC, it is likely that the Monteverde Reserve Complex wouldn't exist in its current capacity.

Monteverde Conservation League (MCL)– Affected Stakeholder

The MCL is a non-profit organization that was established in 1986; this organization was created by a grouping of Monteverde residents with the aim of protecting the forest from agricultural growth[3]. The MCL owns and manages the Children's Eternal Rainforest, the largest private forest reserve in Costa Rica[20]. In its conservation, the MCL collaborates with an extensive set of actors, including the community, SINAC and other government agencies, and other organizations[7]. Between the MCL and the community, there is immense collaboration for environmental education in the CER. In addition to local ties, the MCL collaborates with international institutions to bring researchers into the CER[4].

Costa Rican Conservation Foundation (CRFC)– Affected Stakeholder

The CRFC is an organization that was formed by Monteverde residents and researchers with the intent of protecting the Pacific Slope– this area was deforested due agricultural expansion [26]. The effort to conserve the Pacific Slope is known as the "Pacific Slope Reforestation Project"[26]; this project involved "working with farmers and other landowners, conservation organizations, students, and volunteers"[4]. Moreover, this project overlaps with other projects such as the CBPC, which fosters further collaboration between actors.

Pro-Nativas Monteverde– Interested Stakeholder

The Pro-Nativas Monteverde, is an organization that was established in 2004. This organization was created to highlight the significance of incorporating native tree species in the reforestation projects in the Monteverde Reserve Complex[7]. This organization is not a landholder, and is thus, an interested stakeholder.

The Monteverde Community Fund (MCF)- Interested Stakeholder

The MCF is a non-profit organization that started from a pilot project commenced by the Center for Responsible Travel in 2011[27]. As an intermediary organization, the MCF is heavily involved with the community, and the reserves. A large component of the work the MCF does, is to provide fiscal agency, which is to facilitate funding for projects that the community or organizations are completing[28]. Aside from supporting actors obtain funding, the MCF aims to build capacity within Monteverde[29]. To build capacity, the MCF holds workshops to engage local actors, and connect "Monteverde leaders, organizations, and self-starters with external resources, grant opportunities, and skills"[29]. The role that the MCF holds is similar to Rainforest Alliance and the CINRAM in the case of the Maya Biosphere Reserve; these organizations helped the community forest enterprises develop connections while providing them with fiscal agency to sell xate leaves. In both cases, the organizations held the role of an intermediary organization.

Communities

Communities (Monteverde, Santa Elena, San Luis, La Lindora, Cañitas, and Cerro Plano)– Affected Stakeholder

The communities listed in table 3 are those included in the Monteverde canton– all of these communities are affected stakeholders. Although the not all of these communities are located at elevation with the forest reserves, they all depend on the forests. These communities are resource dependent, thus, if something happens to their surrounding environment, it will have an impact to some extent. The wastewater in Monteverde is an excellent example; if the water in the higher elevation community of Monteverde becomes contaminated, then the communities downstream face the consequences of this water pollution.

Academic Institutions

The Monteverde Institute (MVI)

The MVI is debatably the most important organization in the Monteverde region, it is an non-profit educational organization established in 1986. This organization aims to "guide the increased tourism in a sustainable way by integrating academic programs, research, and community initiatives into programs to benefit both visitors and the local community"[30]. The MVI is connecting actors from different sectors, allowing the co-production of knowledge and conservation in the Monteverde region.

University of Georgia, Costa Rica (UGACR), University of Texas A&M (TAMU-Soltis), and the Colegio Técnico Profesional de Santa Elena (CTPSE)– Affected Stakeholders

The UGCR, TAMU-Soltis, and the CTPSE are all considered affected stakeholders, they are rights holders within the Monteverde region. The UGCR own 60 hectares of forest land beside the Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve where they created a satellite campus; this property is subdivided into three categories: "60% forest, 30% integrated farm, and 10% built space"[4]. The projects this institution completes are primarily oriented around community needs; including agroforestry, composting, and mitigating wastewater[4]. By collaborating with the community members, the institution is able to complete meaningful research and projects that benefit the community. Similar to the UGCR, the TAMU-Soltis owns 120 hectares of forest land bordering the CER[7]. The TAMU-Soltis attracts many researchers annually; the research that they conduct is primarily focused on climate change and its impacts on biodiversity[7]. In addition to this research, the institution has worked with the community and local institutions to build weather stations along the "altitudinal gradient of the Peñas Blancas river watershed and plan to add ecohydrology and vegetation data for each site"[4]. As mentioned, the CTPSE leases land from the ACAT-MINAE and manages the Santa Elena Cloud Forest Reserve. Aside from its responsibility of managing the forest reserve, it engages many local schools in education programs within the SECFR.

Costa Rica National University (UNA)– Interested Stakeholder

The UNA is an interested stakeholder, they are not a property owner in the Monteverde region. This institute collaborates with the other institutes in Monteverde to complete research; it has worked closely with the Commission for Resilience to Climate Change (CORCLIMA) in studying the impacts of climate change in the Monteverde Reserve Complex[4]. By working closely with the other academic institutions, the UNA project capacity has increased considerably over the years.

Government

Monteverde canton, Provincial, and Federal Government– Interested Stakeholders

All three levels of government are considered to be interested stakeholders. The majority of the land within Monteverde is private land, thus, is not owned by the government. However, given the scope of eco-tourism in Monteverde, the region has considerable contributions to the regional, provincial and federal GDP[31]– which inevitably impacts all three levels of government. Moreover, as the Monteverde Reserve Complex belongs to the greater Arenal-Termpisque Conservation Zone (ACAT); this implicates the federal government– this conservation zone is within the jurisdiction of the SINAC and is under the control of the Minister of the Environment.

Discussion

Monteverde is a unique region for a multitude of reasons; it encompasses some of the world's rarest species[12], acts as a hotspot for international research, and has engrained conservation into its management since its establishment[10]. To achieve its status as a sustainable model that fosters a co-production of knowledge and conservation, environmental education and community development, cohesive collaboration between multi-sectoral actors is paramount. The ability of NGOs, academic institutions, local schools, community, and government to effectively operate together is what has allowed Monteverde to exist in its current capacity. Evidently, with the various actors involved in the region, there are certain conflicts.

Between the stakeholders in the Monteverde region, there are numerous aims; among these aims, ecological conservation, environmental education, research, and sustainable community development are prioritized[3]. In addition to the main reserves that have been discussed, there are other reserves that prioritize adventure eco-tourism rather than conservation. Reserves such as SelvaTura, and the Skywalk Sky Trek, focus on attracting people to their reserves through various mediums including zip lines, high lines, and canopy tours[32]. Though there is no educational component to these reserves, they play an integral role in attracting tourists to Monteverde; which generates significant amounts of income in a sustainable way– the construction of the skywalk and zip lines was done to have minimal impacts on the forest ecosystem[32]. In addition to this type of adventure eco-tourism, is the educational focused eco-tourism that takes place in the MCFR, SECFR, BESA, and CER. Out of all the reserves in the Monteverde Reserve Complex, the MCFR receives the most tourists[32]. Within the MCFR, there is the option for visitors that are looking to learn more about the TMCF to have a local guide join them– this is a contributing factor to this reserve being the most popular among visitors[31]. In addition to the education that these reserves provide visitors, they are heavily involved with local schools in promoting environmental education in the community[4]. Within Monteverde region, there are two prominent schools, the Monteverde Friends School (MFS), and the Cloud Forest School (CFL)[4]. Between the reserves and these schools, they form a nexus that fosters utilizing land as a pedagogy while prioritizing traditional Quaker views[7]. Moreover, they unite to complete sustainable projects in the community while integrating findings from ongoing research into their project management. This connection between the reserves, local schools, and researchers enables a unique exchange of knowledge, that results in robust literature that can guide future management in the Monteverde Reserve Complex.

Critical Issues

In general, Monteverde is praised for its conservation efforts; however, there are negatives associated with protecting all the forest around the community[4]. The issue with protecting the entire forest in the region, is it prevents residents from using their surrounding environment. Preventing local residents from engaging with their environment spurs conflict between residents and the forest reserves[7]; this can lead to people attempting to enter the forest reserves illegally and being stopped by the reserve authorities[4]. Evidently, this is problematic, and a wicked problem at that. A plausible solution hasn't been identified, although, incorporating the community in future decisions regarding land use has the potential to address community members concerns.

Evidently, climate change is a prevalent threat to most ecosystems around the world and has had considerable impacts to the TMCF in the past– the alteration of the Golden Toad habitat, leading to its extinction[14]. As a whole, striving to "sustain the local economy, improve quality of life for a growing local population, and continuing to protect the region’s natural capital while adapting to changing climate conditions"[3] are critical issues for Monteverde. As Monteverde is economically dependent on the TMCF, it faces economic instability as climate change influences the cloud forest and biodiversity[3]. To combat this issue, conservation initiatives on both the local and federal level are vital; projects such as the Bell Bird Biological Corridor (CBPC) that are being supported by the local community, NGOs, and through national policy will play an integral role in addressing this issue[3][12]. Moreover, there needs to be multi-sectoral engagement from both the private and public sector– projects such as the (CBPC) can only be effective if the collaboration is transparent and inclusive of all the stakeholders.

Eco-tourism plays an important role in Monteverde, as it accounts for approximately 65%-70% of revenue generated in the region[1]. Despite eco-tourism being the foundation of Monteverde's economy, exponential growth in the industry has had negative impacts on the region's environment and infrastructure[4]. Among the impacts to the environment, is water pollution and the demand for clean water; water pollution has been a concern in the area for numerous years[4]. A large issue with water pollution, is the community members lack of awareness in regards to its existence. To address the issue of water pollution and wastewater, the Monteverde Institute created the Monteverde Special Commission for Integrated Management of Water Resources (CEGIHER)[7]. Together, the CEGIHER and the xxx administer community water and drainage systems (ASADAS)– which receives guidance from the national Institute of Water and Drainage, created educational outlets for community members in attempt to raise awareness surrounding wastewater in Monteverde[7]. In addition to the educational component, the organizations have created prototypes of biogardens and biodigestors to demonstrate different ways to remediate wastewater.

Another concern that was raised by community members, was the inaccessibility of published research[7][4]. Research that takes place in Monteverde has a multitude of benefits, one being to increase local knowledge. However, if local residents cannot access the research due to specialized restrictions or language barriers, it is only a fraction as effective. A solution to improve the accessibility to published work, would be to include an archive of all research in Monteverde at the local library; the Monteverde Institute has begun this process of keeping finished research accessible for local residents[7].

Recommendations

Overall, Monteverde has done extremely well in developing sustainably; they strengthened their economy significantly over time while creating employment opportunities for local residents, have protected their ecologically fragile environment, and improved quality of life in the region. However, as mentioned, there are several existing issues. Below are three recommendations for Monteverde to implement going forward.

The first recommendation that has been suggested, is in regard to keeping a record of organizations, community, and government involvement in Monteverde[4]. This would encompass keeping up to date information on the actors, projects, standing relationships with other entities, and contributions to successful development[7]. Understanding how the projects being implemented over time have evolved is extremely important; having a record of past projects' aims, strengths and weaknesses allows the organization/actor to assess how the project could be altered to be more successful. Moreover, having a transparent report on the relationships between different stakeholders can help identify potential gaps; understanding how stakeholders interact and facilitate each other can highlight gaps– this can allow for the addition of new organizations to fill these implementation/knowledge gaps.

The second recommendation, is to increase the amount of support for research surrounding climate change. It is evident that climate change has had and will continue to have cascading impacts in Monteverde[3]. Understanding the TMCF, and how it will continue to change with the shift in climate is paramount for the Monteverde region. To date, climate change is a focal point for a substantial amount of research in Monteverde. Ensuring that research and projects are properly supported is vital in their success. To support these projects and research, having national and international academic institutions that are financially stable join research in Monteverde is pivotal. As it stands, the University of Georgia and the University of Texas A&M have have become important actors in research regarding climate change in Monteverde[7][4]. Having these large academic institutions allows for collaboration between international and local institutions, and allows the local institutions to build their research capacity. Thus, ensuring the connection between these institutions in the future allows for more research to take place at the local level.

The last recommendation is aimed to dissolve the tension between the forest reserves and the community members. Although the community is already involved in the decision making process in Monteverde, the community members have relatively little power when it comes to managing the forest reserves. The SECFR is the only reserve that has formalised the community in its management. By having the community as an actor in the management of the reserve, the community members concerns are taken into consideration. Thus, if the other reserves were to increase community involvement in the management decisions, it is likely that the issue of land access could be addressed ethically and result in a win-win solution.

Full List of Acronyms

ACAT-MINAE: Arenal-Tempisque Conservation Area and the Ministry of the Environment and Energy

ASADAS: Administer Community Water and Drainage Systems

BESA: Bosqueterno S.A

CBPC: Bell Bird Biological Corridor

CFL: Cloud Forest School

CEGIHER: Monteverde Special Commission for Integrated Management of Water Resources

CORCLIMA: The Commission for Resilience to Climate Change

CRCF: Costa Rican Conservation Foundation

CTPSE: Colegio Técnico Profesional de Santa Elena

MFS: Monteverde Friends School

MCFR: Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve

MCL: Monteverde Conservation League

MVI: Monteverde Institute

SINAC: National System of Conservation Areas

SECFR: Santa Elena Cloud Forest Reserve

TAMUS-Soltis: Texas A&M Soltis Center

TMCF: Tropical Montane Cloud Forest

TSC: Tropical Science Center

UGCR: University of Georgia Costa Rica

UNA: Costa Rican National University

| Theme: Conservation | |

| Country: Costa Rica | |

This conservation resource was created by Levyn Radomske. | |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Cavanagh, E (2005). "Monteverde, Costa Rica: Balancing environment and development" (PDF). Monteverde Institute.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Koens, J; Dieperink, C; Miranda, M (2009). [doi.org/10.1007/s10668-009-9214-3 "Ecotourism as a development strategy: Experiences from Costa Rica"] Check

|url=value (help). Environmental Development Sustainability. 11: 1225–1333. - ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 Newcomer, Q; Céspedes, F; Stallcup, L (2022). "The Monteverde cloud forest: Evolution of a biodiversity island in Costa Rica". Topics in Biodiversity and Conservation. 20.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 4.26 4.27 4.28 Nadkarni, N; Wheelright, N (2014). "Monteverde: Ecology and conservation of a tropical forest- 2014 Update chapters". Bowdoin College.

- ↑ "Monteverde Costa Rica Weather". Monteverde Tours Costa Rica. 2023. Retrieved December 11th, 2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Monteverde Cloud Forest (2021). "Monteverde Cloud Forest".

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 7.20 7.21 Burlingame, L (2018). "Conservation in the Monteverde zone: Contributions of conservation organizations. Update 2018". Bowdoin College.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Depak, R; Nair, U; Lawton, R; Welch, R; Pielke Sr., R (2006). "Impact of land use on Costa Rican tropical montane cloud forests: Sensitivity of orographic cloud formation to deforestation in the plains". Geophysical Research Atmospheres.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Ray, D (2013). "Tropical Montane Cloud Forests". Climate Vulnerability. 5.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Looby, C (2017). "A global view from a mountain town: How conservation became ingrained in Monteverde". Mongabay.

- ↑ IUCN (2020). "Three-wattled Bellbird (Procnias tricarunculatus)".

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Townsend, P; Masters, K (2015). "Lattice-work corridors for climate change: a conceptual framework for biodiversity conservation and social-ecological resilience in a tropical elevational gradient". Ecology and Society. 5: 11.

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 Davis, J (2009). "The Creation and Management of Protected Areas in Monteverde, Costa Rica."". Global Environment: 96–119. line feed character in

|title=at position 50 (help) - ↑ 14.0 14.1 Rainforest Trust (2019). "Thirty Years After the Last Golden Toad Sighting, What Have We Learned?".

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Bosqueterno S.A (2023). "Watershed Property".

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Tellier, G (2023). "Squatters rights on Costa Rica: A comprehensive guide".

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Monteverde Tours Costa Rica (2023). "The history of Monteverde from the 1950's to 2013".

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Philips, R (2015). "What are "squatters' rights" in Costa Rica?".

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Silk, N (1991). "An Ecological Perspective on Property Rights in Costa Rica". Third World Legal Studies. 10. line feed character in

|title=at position 48 (help) - ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Burlingame, L (2019). "History of The Monteverde Conservation League and The Children's Eternal Rainforest" (PDF). line feed character in

|title=at position 50 (help) - ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 Bosqueterno S.A (n.d). "BOSQUETERNO S.A." Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 22.6 22.7 22.8 Corbera, E; Estrada, M; May, P; Navarro, G; Pacheco, P (2011). [doi:10.3390/f2010301 "Rights to Land, Forests and Carbon in REDD+: Insights from Mexico, Brazil and Costa Rica"] Check

|url=value (help). Forests. 2: 301–342. line feed character in|title=at position 59 (help) - ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 "Costa Rica Biodiversity Law- The Legislative Assembly of The Republic of Costa Rica". 1998.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 "What is ACAT?". ACAT. 2023. Retrieved December 11th, 2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2011). "Centro Científico Tropical (Tropical Science Center)". Mountain Partnership. Retrieved December 11th, 2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 26.0 26.1 Fundación Conservacionista Costarricense (2023). "The Costa Rican Conservation Foundation". The Costa Rican Conservation Foundation. Retrieved December 11th, 2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Monteverde Community Fund (2023). "Our Story". Monteverde Community Fund. Retrieved December 11th, 2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Monteverde Community Fund (2023). "Fiscal Agency". Monteverde Community Fund. Retrieved December 11th, 2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 29.0 29.1 Monteverde Community Fund (2023). "Capacity Building". Monteverde Community Fund. Retrieved December 11th, 2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Home". The Monteverde Institute. 2021. Retrieved December 11th, 2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 31.0 31.1 Caldas, V (2009). "Guidelines for sustainable ecotourism in Monteverde, Costa Rica". Tropical Ecology and Conservation [Monteverde Institute]: 286.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Haley, C (2006). "The price we pay: Ecotourism's contribution to conservation in Monteverde". Tropical Conservation and Ecology [Monteverde Institute]: 557.