Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/2021/Wetzin'kwa Community Forest: A Story of Community Success

The Wetzin'kwa Community Forest is located near Smithers, Telkwa, and Moricetown and is part of the Wet'suwet'en First Nation territory[1]. The tenure is held jointly between Smithers and Telkwa in partnership with the Wet'suwet'en Nation[1]. It is 1 of 58 community forest agreements active in the province of British Columbia and has continued to grow in its success year after year[2].

| Theme: Community Forestry | |

| Country: Canada | |

| Province/Prefecture: British Columbia | |

| City: Smithers/Telkwa | |

This conservation resource was created by Natasha Silva. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0. | |

Wetzin'kwa Community Forest

Timeline of Establishing Wetzin'kwa Community Forest[1]

- 1998: community economic development strategy was completed

- 2001: establishment of the Bulkley Valley Forest Community Economic Development Group

- 2003: Softwood Industry Community Economic Adjustment Initiative was tapped to develop a community forest business plan

- 2004: Lynx Forest Management was hired to assess community forest models for profitability

- 2004: Along with the support of the Wet'suwet'en, a request was made to the forest minister for an opportunity to apply for a community forest tenure

- 2005: Smithers and Telkwa with the support of the Wet'suwet'en were invited to apply for a probationary community forest agreement

- 2006: Wetzin'kwa Community Forest Corporation (WCFC) officially incorporated and the management plan was approved by the Ministry of Forests

- 2007: The Wetzin'kwa Community Forest was officially awarded a 5-year probationary community forest agreement on January 1st [3]

- 2010: The Wetzin'kwa Community Forest was officially awarded a permanent community forest licence for a 25-year renewable period[3]

Community Forestry and Community Forest Agreements

Community Forest Agreements (CFAs) are area-based tenures that give the licence holder exclusive rights to harvest timber within that area[4]. CFAs are still subject to provincial restrictions, the province determines the annual allowable cut, the agreement holder pays timber fees for harvested timber, CFA holders are responsible for completing management plans, maintaining an inventory and reforestation, and they can manage for water, recreation, wildlife, and viewscapes[4]. CFAs can be held by a partnership, corporation, society, cooperative, municipality, or First Nation and the application process requires that a community develops a vision that reflects the resident's preferences for forest management[4]. There are three principles associated with community forestry: residents have access to forest lands, opportunities for the participation of residents in management decisions relating to forest lands exist, and an effort is made by communities to protect and maintain the forest they are responsible for[4]. Community forestry is a collaborative governance approach seen as a promising tool for implementing sustainable forest management and devolves decision-making authority to local communities while aiming to increase local benefits from forest use[3]. The province of British Columbia sets the following goals for the community forest program: provide long-term opportunities for achieving community objectives, values, and priorities, diversify the use and benefits from the community forest area, provide social and economic benefits to BC, conduct community forestry consistent with environmental stewardship that is representative of multiple values, promote community involvement and participation, promote communication and strengthen the relationships between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities, foster innovation, and advocate for forest worker safety[5].

Wetzin'kwa Community Forest Corporation (WCFC)

The Wetzin'kwa Community Forest Corporation is the licensee responsible for the management of the Wetzin'kwa Community Forest tenure and is held by the Town of Smithers and the Village of Telkwa in partnership with the Office of the Wet'suwet'en[1]. The WCFC Mission Statement is: "WCFC will manage a profitable community forest tenure while providing good forest management stewardship that will sustain forest resource values for future generations.[1]"

The WCFC is governed by a seven-person volunteer board[1]. Three of these positions are permanent and held by representatives of the key stakeholders: Smithers, Telkwa, and the Office of the Wet'suwet'en[1]. Four positions are held by directors at large and are nominated by the community to hold the position for three years[1]. The WCFC governance structure favours collaboration and provides learning opportunities for forest user groups and community members[6]. Board members share ideas and discuss and deliberate issues through monthly meetings, annual general meetings, forest visits, and informal conversations amongst themselves[6]. WCFC also organizes a forest user group meeting at least once a year to go over management of the tenure and gather input from the groups who use it most[6]. The ability of the board to engage in collective decision-making shows that the board members are united in the desire to make the community forest successful and are committed to getting there through engaged learning and discussions with the community[6]. Building relationships among interested parties when managing natural resources is essential to collective action and can reveal shared interests which help bring the community closer together[6]. One important partnership is the one with the Wet'suwet'en Nation who appreciate that WCFC has created positive experiences with them due to their ability to listen, learn, take action, and take accountability for their decisions[6]. The board works hard to mitigate conflicts that arise through ongoing dialogue, public meetings, user group meetings, discussions with public officials, and more[7].

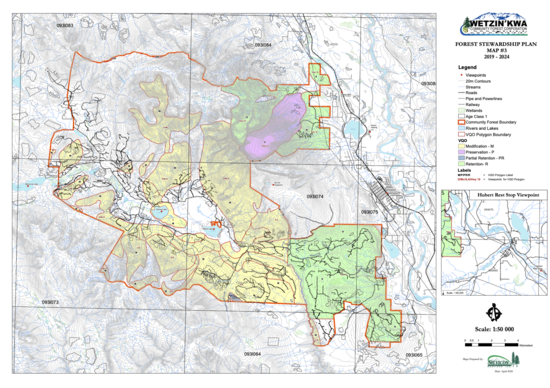

The Wetzin'kwa Community Forest is trying to sustainably manage their forest while prioritizing local employment and protecting cultural values[3]. Major themes of sustainable forest management within the WCFC include ecological sustainability, social sustainability, economic sustainability, and cultural sustainability[3]. The WCFC strictly hires only local companies and contractors to conduct work within and for the community forest[3]. Silvicon Services is a local forestry company that holds the official contract for the operational and day-to-day management of the forest[3]. They take direction from the WCFC board and they provide feedback about operations to the board so that improvements can be made[3]. The WCFC has collaborated with the College of New Caledonia on a climate change experiment and it's part of initiatives like whitebark pine recovery, planting western larch and Douglas fir (in anticipation of climate change), improving stocking standards, and funding grant proposals that can promote or improve forest ecosystems or sustainable forest management[3]. The WCFC follows the rules and regulations of the Bulkley Land and Management Plan and those of the Forest Range and Practices Act, examples include encouraging young willow growth, deactivated winter roads, and leaving wildlife patches after logging[3]. Maintaining understory is another big component of forest management in the Wetzin'kwa Community Forest[3]. The WCFC plants trees that are appropriate to the ecosystem of the Bulkley Valley and through the partnership with the Wet'suwet'en, WCFC receives information on rare species which aids in biodiversity management[3]. This collaboration with the Wet'suwet'en Nation has allowed the WCFC to manage watershed and riparian areas beyond what's required by the government and the Wet'suwet'en have been able to protect their medicinal and cultural plants before any logging occurs in areas they may be located[3]. WCFC also supports and works with local recreational groups like the Smithers Community Forest Society, the Smithers Mountain Bike Association, and the Bulkley Valley Cross-Country Ski Club. They also organize community events to walk in the community forest and invite the community to their annual general meeting; participation in these events has been minimal in the past[3]. The Wetzin'kwa Community Forest tenure has undergone one replacement to date[7].

Forestry Practices: Operations and Silviculture in 2020-2021 Season

Operations

Annual harvest plans mainly consist of stands that have significant dead timber volumes from Mountain Pine Beetle and Balsam Bark Beetle infestations[8]. 24,353m³ of timber was harvested from the tenure area and an additional 2,231m³ was harvested under a Forest Licence to Cut[8]. The majority of the harvested timber went to Pacific Inland Resources in Smithers, BC, and a couple of other small local processing mills[8]. The volume that was harvested under the Forest Licence to Cut was cut to create a fuel break along Hudson Bay Mountain Road[8]. The fuel break will help protect the cabin community and the ski hill infrastructure[8]. The project is being aided by the BC Wildfire Service who is providing valuable input to ensure this initiative will reach its desired outcome[8].

The Wetzin'kwa Community Forest is continuing to work at reducing wildfire risks and is actively working with the BC Ministry of Forest, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, BC Wildfire Services, Mountain Resorts Branch, Recreation sites and Trails BC, and the Gitdumden Clan of the Wet'suwet'en Nation to create more landscape-level fuel breaks to better protect the lands from the ever-increasing wildfire risks[8].

Silviculture

The Wetzin'kwa Community Forest Corporation planted 474,072 seedlings, the majority in the summer of 2020 and the rest in the spring of 2021[8]. They opted for the busier summer planting season because in 2020 the province of BC had decided to implement its largest spring planting season in history and the WCFC was worried about the difficulties of finding planting companies with the large amount of competition such an initiative brings[8]. They had also decided to use the spring to do fuel reduction work and didn't want the seedlings harmed while that was ongoing[8].

Core Values

The Wetzin'kwa Community Forest has five core values: cultural, economic, ecological, recreational, and community[1]. Under these core values, they aim to sustain a financially viable forest enterprise for the long-term benefit of the Bulkley Valley, maintain ecosystem integrity, protect water quality, maintain a healthy balance of all plant and animal species, recognize the Wet'suwet'en and their culture, establish long-term respectful relationships, expand local small business and employment, provide a safe and environmentally friendly work environment, enhance outdoor education and recreation, increase community involvement in resource management, and to reflect community values in all decision-making[8].

Cultural Value

The objective of the cultural value is to protect and conserve cultural heritage sites, features, and values while maintaining a good working relationship with the Wet'suwet'en Peoples[1]. An example of this is WCFC's policy for harvesting and road development plans: they are always referred to the Office of the Wet'suwet'en to ensure that known cultural heritage sites and resources are both identified and protected.[1]

Economic Value

WCFC's goal is to manage the economic values of the community forest and use them to expand local small business opportunities[1]. They also aim to increase employment in the forest sector through the community forest and in the town through small businesses using the grant program[1].

Ecological Value

The Wetzin'kwa Community Forest consists of 30,000ha and is located in four biogeoclimatic zones: sub-boreal spruce, interior cedar-hemlock, Engelmann spruce-subalpine fir, and alpine tundra[1]. The community forest also features 400ha of lakes, 400km of streams and river systems, and 40ha of wetland ecosystems[1]. The Wetzin'kwa Community Forest is an expansive habitat for many species, some of which include lynx, deer, moose, grizzly and black bears, mountain goat, wolves, wolverines, and more[1].

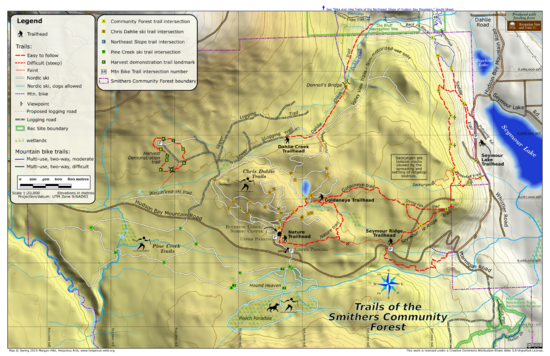

Recreational Value

Recreational activities in the community forest include hiking, mountain biking, ice climbing, cross-country skiing, downhill skiing, and more[1]. The WCFC partners with forest user groups to help them improve the areas of the community forest they use for recreation[1]. An example of this is the partnership between WCFC and the Bulkley Valley Cross-Country Ski Club who they helped to develop and maintain the ski trail network at the Nordic Centre[1]. The Wetzin'kwa Community Forest contains 200km of cross-country skiing trails, 100km of hiking trails, 20km of multi-use trails, 20km of mountain biking trails, and 4km of snowmobile access[1].

Community Value

Each year, the Wetzin'kwa Community Forest Corporation distributes funds back to the community through its annual grant program and stakeholder donations [1].

Key Stakeholders

Town of Smithers

Smithers is located in Northwest British Columbia along the Yellowhead Highway[9]. The town is governed by six councillors and one mayor with an election every four years[9]. Top things to do in town include but aren't limited to: mountain biking, skiing, snowboarding, craft eateries, breweries, cafes, hiking, horseback riding, and shopping along Main Street[9]. Smithers was incorporated as a village in 1921 and reincorporated as a town in 1967[10]. It is situated at the halfway point between Prince George and Prince Rupert and is often referred to as the 'Gateway to the North[10].' Smithers features Hudson Bay Mountain to the west and the Babine Mountain Range to the east[10]. Smithers population as of the 2016 census is 5,401[10]. The main industries in Smithers are forestry, agriculture, tourism, and mining[10].

Village of Telkwa

Telkwa was incorporated into a village in 1952[11]. It is located along the banks of the Bulkley and Telkwa rivers and features extensive outdoor and recreation activities[11]. Telkwa is also within driving distance of both Smithers and Houston, BC[12]. The Bulkley and Telkwa rivers are two major world-class salmon-bearing rivers[12]. Telkwa means 'river flowing north.[12]' Some of the extensive year-round outdoor activities include hunting, sport fishing, hiking, cycling, canoeing, tubing, rafting, kayaking, paddleboarding, bird watching, snowmobiling, Nordic skiing, snowshoeing, skating, ice-fishing, and downhill skiing[12]. The main industries in Telkwa are forestry, agriculture, and tourism, and their population according to the 2016 census is 1,327[11].

The Wet'suwet'en First Nation and the Office of the Wet'suwet'en

The Wet'suwet'en First Nation is made up of numerous bands including Skin Tyee Band, Nee Thai Buhn Band, Wet'suwet'en First Nation, Moricetown Band, and Hagwilget Band[13]. The Wet'suwet'en First Nation is located west of Burns Lake, BC[13]. They are formally known as the Broman Lake Indian Band and they speak the Witsuwit'en dialect of Babine-Witsuwit'en[13]. Their main community is the Palling Indian Reserve No. 1 and approximately 255 members live on and off reserve lands[13].

The Office of the Wet'suwet'en is a central office located in Smithers, BC that offers services that focus on lands, resources, human and social services, and governance[14]. Their Mission Statement says, "we are proud, progressive Wet'suwet'en dedicated to the preservation and enhancement of our culture, traditions, and territories; working as one for the betterment of all.[14]" Their strategic goals are to ensure a self-reliant nation, an effective, responsible, and accountable infrastructure, continual and effective communications, responsible jurisdiction of resources for equitable and sustainable use, effective financial management, and lastly to ensure a government model based upon the foundation of the Wet'suwet'en hereditary system[14]. Their natural resource department's purpose is to "protect all lands and resources of Wet'suwet'en territory for the benefit of the Wet'suwet'en, develop capacity for economic development of our communities, and to preserve these resources for our children and generations to come."[14] The Office of the Wet'suwet'en works in partnership with the Town of Smithers and the Village of Telkwa to make decisions in the community forest but they are not a legal tenure holder[7].

Benefits and Positive Impacts of the Community Forest

Annual Grant Program

Each year the WCFC gives $250,000-$300,000 in community grant funding[1]. This past year saw more than twenty recipients receive grants from the WCFC[15]. Proposals for the annual grant can only be submitted for activities taking place in the Witset, Smithers, and Telkwa area by non-profit or registered charity organizations[1]. The grant application categories include arts and culture, recreation, environment, conservation and natural resource management, social services, and community economic development[1]. The WCFC has also established a Legacy Fund that ensures the community grant program will continue to run even in years that little to no harvesting occurs[1].

Community Investment

Annual profits from the Wetzin'kwa Community Forest get invested back into the Bulkley Valley community[16]. This is through WCFC's grant program and development initiatives. In 2020, the major investment was in roadbuilding and maintenance of pre-existing roads[16]. The WCFC was responsible for the funding of 8km of road that had either been upgraded or newly constructed; they also installed three bridges and a major culvert[16]. In 2020, approximately $300,000 was given back to the community and over the last 13 years, the WCFC has contributed approximately $2 million to the community[16]. The Wetzin'kwa Community Forest has been beneficial fiscally because instead of the funds going to the province they get invested within the community[7] which has allowed the WCFC to contribute to initiatives like the community disaster relief fund[15]. In addition to the grants and infrastructure, the WCFC gives back to the community's economy by ensuring all jobs pertaining to the community forest and the community forest corporation go to local people[15]. Many people within the community have also benefited from the recreation facilities the community forest has helped fund[7]. Each of the three key stakeholders: the Town of Smithers, the Village of Telkwa, and the Office of the Wet'suwet'en all receive an annual contribution of funds during profitable years which they can distribute within their communities as they see fit[7]. This year, each of those stakeholders will be receiving $40,000 in funding[8]. In addition to the grant program and stakeholder donations, the WCFC also donates to the Smithers Community Services Association, the Salvation Army, and the Bulkley Valley Foundation[8].

Community Involvement

Community involvement is immensely integral to successful community forestry and is an important component of the way the WCFC operates. For example, the WCFC held an open house with the community to address the problem of the pine beetle and to determine the best way to harvest the infested trees within the community forest tenure[17]. The Wetzin'kwa Community Forest contains 1.7 million cubic meters of pine and it's estimated that 60-70% will die due to pine beetle infestation[17]. The WCFC wanted to harvest the infected trees with the least harm possible and openly discussed concerns with the community including the fact that unharvested infested trees don't get replanted which leaves a forest of standing deadwood, there are planning issues, watershed issues, and wildlife issues around harvesting in general, and the dead trees pose a serious fire risk[17]. This is an issue that has been a research point in the area for the last ten years. The community forest has also allowed the community to benefit from recreation activities, gain employment, gather firewood, and have been able to both witness and provide input on unique forest management practices[7].

Discussion

The Wetzin'kwa Community Forest is considered to be a story of success and has provided considerable benefits to the community as a whole[7]. A large part of Wetzin'kwa's success is due to the excellent relationships the WCFC maintains with the Wet'suwet'en Nation and the entirety of the Bulkley Valley[7]. The WCFC emphasizes the community part of community forestry and has proven that it is of great importance[7]. Thought has been put into the formation of the board for WCFC too and is another component of success. Wetzin'kwa Community Forest is directed by WCFC's seven-person volunteer board and has no official employees[7]; when work is done in the community forest it is always contracted to local companies[7]. None of the board members are government employees, mill employees, people involved in local forest management, or part of town councils[7]. The board does this to minimize conflict of interest and they also work hard at being reactive to changing policies and directions as needed for the community at large[7].

When looking at other community forests in BC, there are a few similar attributes that contribute to either the success or failure of implementing a community forest. The North Island Woodlot Association tried and failed to implement a community forest[18]. They are a community of Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous people and securing the support of the Indigenous Peoples proved to be difficult due to ongoing land claims[18]. Because of the lack of social cohesion, there was inadequate community support which led to the failure to secure a community forest[18]. The Nuxalk First Nation also tried to implement a community forest but they too didn't have community support[18]. There was an election that resulted in leadership change and the new leader chose not to pursue the community forest proposal[18]. The Harrop-Proctor Community Forest was successfully implemented because both the communities of Harrop and Proctor shared a similar environmental and ecological identity and both were in support of the initiative[18]. They didn't have issues with the local First Nations in terms of implementing it and they've found success in selling both value-added timber and non-timber forest products[18]. All of these examples showcase that community support and community participation are key to the successful implementation of community forests and can make up for limitations in forestry expertise and experience[18]. For Wetzin'kwa, the community support and opportunities for community participation from its inception have certainly aided in its success. Forestry and tourism being central industries in both Smithers and Telkwa also seem to point to a community forest being an ideal addition for both communities. Having a community forest also aids the bigger picture in attracting more people to move to such an environmentally focused town and village. It's also interesting to note that the mission statement from the WCFC and the Natural Resource Department Purpose of the Office of the Wet'suwet'en have several similarities and both have a central theme of working towards bettering the land for future generations to come.

For Gary Hanson, one of the WCFC board members, the community forest has given him the opportunity to volunteer for a good cause[7]. After retiring he felt it was time to give back to the community that had provided a wonderful home and place to raise a family[7]. When asked about changes that could be made for the community forest in the future, Gary Hanson mentioned that the Bulkley Timber Supply Area Land Resource Management Plan was completed in 1996 and that it covers the entire TSA including the community forest[7]. Hanson is optimistic that since that time, there has been considerable knowledge gathered on the community forest and it could be sufficient enough to develop a mini Land Resource Management Plan for the tenure area of the community forest[7]. This would involve heavy negotiations with the local Ministry of Forests but if successful would make Wetzin'kwa Community Forest an even greater success and an example of how community forestry can continue to grow in the ways it can help and support the communities they're found in[7]. Wetzin'kwa Community Forest has been successful because of how well-rounded it is: it emphasizes community relationships, First Nations relationships, has thought about how to provide benefits for the long-term, and continues to grow and be successful each year. Every community forest in the province is different because the communities they are part of are different, however, there are valuable lessons to be learned from Wetzin'kwa's success and could potentially be applied to existing and soon-to-be community forests throughout BC.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 Wetzin'kwa Community Forest. Wetzin'kwa Community Forest. (2021). Retrieved 7 November 2021, from https://www.wetzinkwa.ca.

- ↑ British Columbia Community Forest Association – Local Forests, Local People, Local Decisions. Bccfa.ca. (2021). Retrieved 12 December 2021, from https://bccfa.ca.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 Assuah, A., Sinclair, A. J., & Reed, M. G. (2016). Action on sustainable forest management through community forestry: The case of the Wetzin'kwa community forest corporation. Forestry Chronicle, 92(2), 232-244. https://doi.org/10.5558/tfc2016-042

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Furness, E., Harshaw, H., & Nelson, H. (2015). Community forestry in British Columbia: Policy progression and public participation. Forest Policy and Economics, 58, 85-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2014.12.005

- ↑ Bullock, R., & desLibris - Books. (2017). In Bullock R., Broad G., Palmer L. and Smith M. A. (.(Eds.), Growing community forests: Practice, research, and advocacy in Canada. University of Manitoba Press.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Assuah, A., & Sinclair, A. J. (2019). Unraveling the relationship between collective action and social learning: Evidence from community forest management in Canada. Forests, 10(6), 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10060494

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 Hanson, G. (2021, December 4). Personal interview. [Personal interview].

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 Wetzin'kwa Community Forest Corporation. (2021). Annual Report July 1, 2020 to June 30, 2021.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Town of Smithers. (2021). Retrieved 7 November 2021, from http://www.smithers.ca

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Town of Smithers :: RDBN. (2021). Retrieved 7 November 2021, from https://www.rdbn.bc.ca/departments/economic-development/regional-information/area-profiles/municipality-profiles/smithers-profile

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Village of Telkwa :: RDBN. (2021). Retrieved 7 November 2021, from https://www.rdbn.bc.ca/departments/economic-development/regional-information/area-profiles/municipality-profiles/smithers-profile

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Telkwa.ca. (2021). Retrieved 7 November 2021, from https://www.telkwa.ca/about.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 About Wet'suwet'en First Nation. Wet'suwet'en First Nation. (2021). Retrieved 7 November 2021, from https://wetsuwetenfirstnation.com/about-wetsuweten-first-nation.html.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Wet'suwet'en, O. (2021). Office of the Wet'suwet'en. Wetsuweten.com. Retrieved 7 November 2021, from http://www.wetsuweten.com.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Bakker, M. (2020, ). Wetzin'kwa community forest gives out $300K in annual grants. The Interior News

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Bakker, M. (2020, ). Wetzin'kwa community forest corporation spends big dollars on road building. The Interior News

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Bolen, K. (2010, ). Pine beetle program among discussion on Wetzin'kwa community forest. The Interior News

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 McIlveen, K., & Bradshaw, B. (2009). Community forestry in British Columbia, Canada: The role of local community support and participation. Local Environment, 14(2), 193-205. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830802522087