Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/2021/Conservation, Development, and Dragon’s Blood: A Social Forestry Case Study of Socotra Island, Yemen

The island of Socotra, off the coast of Yemen, is home to the Indigenous Socotri people as well one of the Earth’s oldest and most unique forested ecosystems – highlighted by the world-renowned population of endemic dragon’s blood trees (Dracaena cinnabari). Local communities currently practice informal management of the island’s forests and wider natural resources through traditional resin harvesting, gathering of other non-timber forest products, and the indirect impact of transhumance pastoralism. In the last 30 years, the historical equilibrium between the island’s people, livestock, and rich biodiversity has begun to erode as global conservation interests, international tourism, and mainland political turmoil have disrupted traditional livelihoods and accelerated human-induced pressures to the increasingly climate-stressed natural environment. In the face of these shifting conditions, the potential of social forestry on Socotra offers a path to securing justice, livelihoods, cultural heritage, and environmental sustainability to the benefit of local people and nature.

Introduction

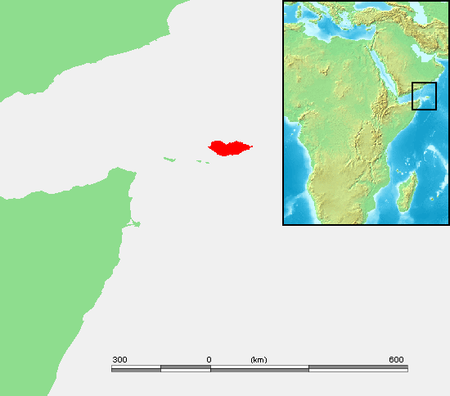

Socotra (or Soqotra) is the largest of several islands in the Socotra Archipelago in the western Indian Ocean some 380 km off the coast of the Arabian peninsula. The island is controlled by the Republic of Yemen, although the ongoing civil conflict in mainland Yemen has strained these ties in recent years. The landscape of Socotra consists of about 3,600 square kilometres of dry tropical forests, coastal plains, limestone plateaus, and mountain peaks. The island, often referred to as the “Galápagos of the Indian Ocean,” is revered for its rich biodiversity.[1] It is home to over 800 species of plants (37% of which are endemic), 34 species of reptiles, 192 bird species, and many other unique organisms.[2]

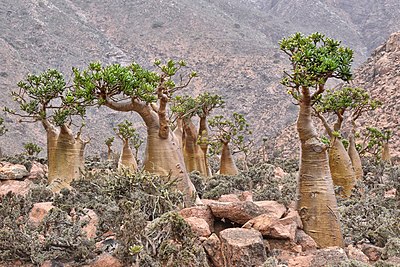

Of particular importance to the history of the island are the unique and ancient tree species that populate the inland slopes and plateaus – including the Frankincense tree (Boswellia elongata), bottle tree (Adenium obesum), and, most notably, the endemic dragon’s blood tree (D. cinnabari). The dragon’s blood tree is listed as a Vulnerable species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and faces threats from a changing climate, livestock grazing, and damage by human use.[4][5] The species is named for the thick, red resin that is collected from cuts in the tree surface by local people for traditional use in medicines, adhesives, food additives, and, more recently, as a material used in handicrafts sold to tourists.[3] Dragon’s blood trees have important mutualistic relationships with other flora and fauna on the island, including several species of endemic reptiles.[4] The tree forms a striking, tightly packed crown shaped like an open umbrella, that helps to capture moisture carried in air masses from the sea in a climate that is otherwise arid for 8 months of the year. The Firmihin forest contains over 40% of the island’s population of dragon’s blood trees and is considered to be one of the oldest forested ecosystems in the world.[6]

The island has been continuously inhabited by Indigenous Socotri people for over 3,000 years. It was a hub for the regional incense and spice trade between the Arabian peninsula and Greek and Roman empires between about 700 BCE and 400 CE.[7] For much of its history, the inhabitants of Socotra have been subjected to outside rulers – mainland sultans, Portuguese occupation, British rule in the early 20th century, and modern statehood as part of the Republic of Yemen.[8] The local human population, along with their livestock, have shaped the natural environment of the island for millennia, creating an ecological equilibrium that is now facing rapid change since the opening of modern Yemen to the outside world following unification in 1990.[7] The last 30 years have been defined by an influx of international conservation and development attention centered around the island’s unique natural environment. Forces of globalization, a growing ecotourism industry, and regional nation-state actors have led to the slow erosion of traditional livelihood practices and, as a result, an increased vulnerability of the once resilient forest ecosystem that has defined Socotra for millennia.

| Theme: Social Forestry | |

| Country: Yemen | |

| Province/Prefecture: Socotra | |

This conservation resource was created by George Charlie Thorman. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0. | |

Stakeholders

Affected Stakeholders

The primary affected stakeholders involved in forest and land management on the island are the local Indigenous people of Socotra. Nearly all of the island’s roughly 50,000 inhabitants are part of the Socotri ethnic group that have lived on the island for millennia. Socotri people are considered part of the wider Bedouin peoples of North Africa and the Arabian peninsula, although this identity is more strongly held among the nomadic pastoralists on the island.[9] Although the local people share a common ethnicity, they are by no means a homogenous population. One noteworthy division amongst the population is between coastal communities – including the two largest towns on the island, Hadiboh and Qalansiyah – and smaller interior settlements.[9] Coastal communities have traditionally relied on fishing, agriculture and trade for their livelihoods while the island’s interior population more commonly practices transhumance pastoralism. The population’s close ties to the terrestrial environment also includes harvesting non-timber forest products (NTFPs) (resin, frankincense, and animal fodder) and occasionally collecting firewood from neighbouring forests for income generation or fuel.[3]

Sustainable management of the island’s forests and connected ecosystems has been crucial to the pastoral livelihoods and cultural heritage of Socotra’s interior communities. Forest management occurs informally through traditional resin harvesting practices and livestock management.[3] However, these practices have begun to deteriorate in the last 30 years as village markets selling imported meat, bottled water, and fuel have proliferated and decreased the value of livestock and other local natural resources. Young Socotris are increasingly abandoning their pastoral roots and moving to the coast or abroad for greater economic opportunities.[10] This pull towards outside opportunities reflects the vulnerable position of many Socotri people. Traditional livelihood practices and the Socotri language are not valued in a society that is increasingly at the mercy of outside decision-makers that operate in Arabic and English. Furthermore, the Yemeni state does not recognize the Indigenous status of the Socotri people and the long history of foreign occupation over the last several hundred years has left the Socotri people at the bottom of a seemingly insurmountable power imbalance.[8]

Interested Stakeholders

The perceived global value of Socotra’s endemic flora and fauna has attracted the attention of many interested stakeholders since the 1990s. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), IUCN, and BirdLife International are among the many international organizations that have funded projects on the island. Conservation efforts have also attracted a host of international researchers from academic institutions in Italy, Belgium, the Czech Republic, and beyond.[11] The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh has been involved in botanical research in Socotra since the very first modern survey of island flora was conducted in 1880.[10] These outside stakeholders hold a high degree of power due to the funding they provide and the value placed on western science in international conservation. Local people have little incentive to say no when outside organizations arrive offering large sums of money for predetermined projects even if their consultation process with local communities is lacking.[10]

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) added the Socotra Archipelago to the Natural World Heritage List in 2008 on the basis of the island’s outstanding universal value for biodiversity conservation.[2] It is worth noting that this Natural Heritage listing does not seek to protect the Cultural Heritage of the Socotri people.[10] UNESCO has worked closely with the Socotra branch of Yemen’s Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) and the Socotra Conservation and Development Programme (SCDP) to deliver benefits to local communities with mixed results.[12]

Additionally, in the last several years, the United Arab Emirates has emerged as an active outside interest in Socotra. In 2015 the UAE established a “humanitarian protectorate” on the island in the wake of two cyclones that caused widespread damage.[8] This occurred just one year after the Houthi movement overthrew the Yemeni central government in Sana’a, leaving a power vacuum over the remote off-shore territory. As civil war and political instability has continued to occupy the mainland, the UAE has maintained their presence on Socotra. They have elevated their role in local conservation and development initiatives by instituting their own officials in a parallel governance system alongside Yemen’s existing framework.[8] In this context, it is believed that the UAE sees Socotra as a strategic asset to their wider geopolitical ambitions in the region.[8]

Governance & Institutions

Before unification, and continuing informally through Socotra’s inclusion in the modern Yemeni state, local tribal authority has provided the primary source of governance for the local population. This system includes a complicated, customary land tenure system of overlapping clan-based land claims that remains in place today despite added administrative structures imposed by the federal government.[6] In this context, no formal management plans govern the interaction between local people and forests. Instead, communities act as de facto forest management authorities, guided by unwritten rules on animal husbandry and harvesting of NTFPs.[3]

Around the turn of the century, the Yemeni federal government began to take a more active role on the island. This shift occurred due to international pressure to decentralize the authority of the state. In reality however, the Local Authority Law, which was passed in 2000 to establish a district-level system of elected local councillors, gave more top-down control to the federal government.[8] Under this system, the General Director of each district was appointed by the central government and budgetary control was maintained by higher levels of government while service provision was delegated to local authorities.[8] Effectively, this shift handed over responsibility for conservation and development outcomes to lower levels of government without empowering those institutions with the autonomy or human resources to effectively pursue sustainable outcomes.

Of particular importance during this transition was the establishment of the Conservation Zoning Plan (CZP), which was created in 2000 and implemented by the EPA over the following decade. The CZP established national parks, protected areas, and resource-use zones through a collaborative process involving local people and foreign experts. However, the actual level of input elicited from local communities and the circumstances around that process are not well documented.[10] Among other actions, the CZP introduced bans on certain agricultural practices, regulation of the import and export of biological materials, and building restrictions in protected areas.[11] In some places, local communities approved of nature sanctuaries and helped with the construction of ecotourism campsites based on an understanding that they would share in the revenue from a new ecotourism industry. In other locations, such as the Firmihin forest, villages negotiate to avoid strict protections and to instead maintain natural resource use rights for local people.[11]

Unfortunately, the primary shortcoming of the Conservation Zoning Plan has been the inability of the EPA to follow through on many of its ambitious goals to limited funding and ineffective governance.[6] Following the designation of protected areas in the early 2000s, individual management plans were developed to protect and restore natural areas while providing economic benefits to local communities through neighbouring resource-use locations. In the absence of strong institutions, these plans went largely unfulfilled over the following decade.[11]

In recent years, the already under-resourced formal government institutions on Socotra have been further stressed by political upheaval in the wake of the 2014 coup in mainland Yemen. Both the exiled federal government and the incoming Houthi rebels claim authority over the nation’s extant regional offices.[8] But with their attention devoted to the more pressing concerns of civil war on the Arabian Peninsula, governance in practice on Socotra has remained in the hands of local traditional authorities as well as the encroaching presence of UAE administrators.

On the whole, poor governance and administrative capacity have had negative impacts on people and the natural environment of Socotra. State-run institutions have largely lost the trust of the local population[8] and the IUCN has recently recommended that Socotra be moved to UNESCO’s World Heritage in Danger list based on deteriorating conservation outcomes.[13]

Critical Issues

The people, forests, and wider landscape of Socotra are in the midst of a period of significant change over the last several decades. These changes stem from the influence of outside interests on a society and natural environment that had, until the 1990s, enjoyed a high degree of isolation from the outside world. In the last 30 years, Socotra has seen the arrival of international conservation and development NGOs, an increased presence of mainland Yemeni government structures, foreign tourists, and, more recently, the infiltration of regional powers into local governance. In this context, I will discuss three critical issues that illustrate the numerous, overlapping challenges facing the Socotri people and their management of forests in the 21st century – degradation of forest health, conflicts surrounding road building, and the racialization of the landscape.

Declining Forest Health

As previously mentioned, Socotra is home to several economically and culturally significant tree species including frankincense and cucumber trees and the prominent, endemic dragon’s blood trees. The resin of dragon’s blood trees has been harvested by local people for millennia for use in medicines, adhesives, and cultural practices. In recent years, the endemic nature and striking visual appearance of the species has made it the centerpiece of the global attention received by the island for biodiversity conservation and ecotourism.[6] Therefore, much has been made of the declining range and health of the island’s D. cinnabari population. A remote sensing survey conducted by Maděra and colleagues[6] estimated that nearly 1/3rd of the island’s roughly 80,000 dragon’s blood trees faces a high threat of local extinction in the immediate future. Furthermore, the realized niche of dragon’s blood trees (where trees are actually found) covers just 5% of the area where biogeoclimatic conditions suggest the trees could grow historically.[14] It is believed that direct and indirect human impacts, along with changing climatic conditions, are responsible for these troubling statistics.

The Firmihin forest, which is home to about 40% of the species endemic population, is repeatedly highlighted as a location of paramount concern. The forest hosts the largest intact range of dragon’s blood trees on the island as well as 7 local villages with about 300 residents.[3] Historically, the relationship between the Firmihin villagers and the local dragon’s blood trees has been mediated by sustainable resource use practices that have begun to erode during the recent period of social and environmental change. Local communities have traditionally managed resin harvesting with a series of informal rules, including only harvesting during a timeframe established by village leaders, using small knives rather than axes or stones, and widening old wounds in the trees rather than creating new ones.[3] This traditional management, built around strong social bonds, is similar to the mushroom harvest system of the people of Naidu Village in Yunnan, China.[15] The Naidu villagers, unlike rural Socotris, have benefited from effective state interventions to protect their traditional practices from outsiders.[15] By contrast, adherence to sustainable resin harvest practices has declined in the Firmihin forest as rising market prices have attracted unregulated harvesters from neighbouring communities.[3] Even so, harmful resin harvesting only impacts a small portion of the island’s forests, making it a sideshow in the wider conversation on forest health.[16]

The greater threat to the dragon’s blood tree population is their low rate of regeneration driven by climate change and shifting grazing patterns. For thousands of years, traditional transhumance livelihoods ensured an ecological equilibrium between grazing goats and the vegetation on the island.[7] However, recently, grazing pressure has increased in concentrated areas as more Socotris have settled in towns.[17] Also, better access to veterinary care and alternative water sources have meant that goat populations have increased as fewer animals die due to drought and other natural causes.[17] The end result is that increased grazing pressure depresses the already low regeneration rates of the island’s dragon’s blood tree population.

However, the greatest impact facing Socotra’s forest resources is likely the effect of climate change on the island’s fragile ecosystem. Much of the land currently occupied by D. cinnabari and other tree species on the island is now much drier and warmer than it was when these populations were established hundreds of years ago.[14] Indeed, the highest levels of regeneration are found on cooler, higher elevation hillsides that capture more moisture from drifting ocean mist.[10] While mature trees can often withstand periods of drought, the impacts will become more pronounced as more trees reach the end of their natural life cycle and fewer seedlings establish to replace them. Climate scenario modelling predicts that the range of dragon’s blood trees will decrease by 45% by 2080 due to increased aridity.[14] In this way, global fossil fuel use and consumption practices that have largely passed over Socotra until recent years, are having profound impacts on the people and natural environment of the island.

Road Building

Around the globe, road building is a common point of conflict between development and conservation interests. Roads can provide remote communities with access to markets, improved social services such as healthcare and education, and alternative livelihood opportunities.[18] However, this form of infrastructure development also brings new challenges like habitat fragmentation and increased pressures on formerly secluded ecosystems.

In Socotra, conservation and development actions proliferated across the island in the 1990s as international organizations rushed in to study and preserve the island’s biodiversity. Among other purposes, the Conservation Zoning Plan, implemented by the EPA starting in 2000, was meant to limit the expansion of roads networks and human settlements on the island.[11] However, for many years, one federal agency in charge of infrastructure development – the Ministry of Roads – disregarded CZP restrictions and continued to build in protected areas.[11] During this time, weak local governance proved unable to enforce the CZP’s land-use regulations and, as a result, between 2001 and 2013, over 900 km of road were built on the 130 km long island.[7]

The island’s road network has benefited the local population by increasing connectivity, especially between remote interior villages and social services in coastal communities. Food security for rural villages has been improved through greater access to markets and imported packaged food.[10] At the same time, however, the proliferation of roads on the Socotra has had a negative impact on the biodiversity of the island. The roads and the vehicles that travel them are a source of runoff and pollution that have detrimental effects on the wider environment.[17] They also accelerate the spread of invasive species that arrive at the island’s ports and airport and move inland over time.[11]

Most importantly, the roads provide access to locations that were previously protected from human impact due to their remote location. The Firmihin forest, for example, is one of several natural attractions that have become regular stops by foreign tourists seeking to experience the ecological beauty of the island.[10] Before the recent conflict on mainland Yemen slowed foreign visitors, the number of tourists visiting Socotra ballooned from only a couple hundred in 2000 to over 5,000 per year less than a decade later.[7] Despite the attention given to ecotourism by international organizations and the federal government as a potential driver of economic diversification, the industry has largely developed in an unregulated and unplanned manner.

In addition to foreign visitors, the expanding road network has increased natural resource exploitation by the local population. Human and grazing pressures on previously remote forests have risen as transportation infrastructure has spread around the island.[14] In summary, the expanding presence of roads on Socotra has triggered increased land-use competition, whether for human settlements, tourism, grazing, or other extractive uses.

Racialization of the Landscape

In light of Socotra’s history of influence and control by outside political powers, it is important to discuss the racialization of the island’s landscape – i.e. the objectification of a minority community by a dominant ethnic group. Cultural anthropologist Nathalie Peutz, who lived among local communities in Socotra for several years in the early 2000s, describes a cultural divide between the more rural, nomadic Bedouin communities and the coastal population with closer ties to outside Arab influences.[9] Among the local people there is a negative view of their own Bedouin identity as “backwards” or “primitive".[9] Peutz suggests that the influence of globalization since the early 1990s has exacerbated the power asymmetries between the traditional Socotri population and the mainland Arab Yemeni state. Square-cornered “Arabic” houses, imported packaged food, qat chewing in place of traditional tea culture, and regional branches of federal government ministries all contribute to the increased visibility of Arab identity on the island and, as a result, the marginalization of Bedouin and Socotri culture.[19][9]

Language has perhaps played the strongest role in this societal divide. The Yemeni government conducts its official functions on the island in Arabic only, thereby eroding the value of the local Socotri language.[19] In recent years, Emirati influences have initiated Arabic language poetry competitions on the island to directly oppose the rich cultural history of Socotri poetry.[10] In combination, these conditions pressure local communities to abandon their ethno-linguistic heritage and embrace a “modern” Arab identity defined by the mainland state and regional powers.[19]

However, there exists a simultaneous push by the Yemeni government and some development programs to romanticize the local Bedouin identity as a tactic to grow the island’s tourism sector. Bedouin hospitality and traditional, nomadic livelihoods are co-opted and commodified across the Arabian Peninsula and North Africa to create a false picture for tourists of pristine landscapes complete with noble, primitive people.[9] In this way the Socotri people are caught in a paradox where they are pressured to both embrace and reject their ethnic identity as their island forges forward into a modern, globalized world.

The racialization of Socotra’s landscape is similar to the dynamics of another island case study documented by researcher Nicholas Menzies in his book “Our Forest, Your Ecosystem, Their Timber”.[20] Zanzibar, off the coast of Tanzania in East Africa, was for centuries, like Socotra, an important site in the global spice trade ruled by outside powers. After Tanzania’s independence in the 1960s, Menzies describes a cultural and political divide between the Indigenous African population and the formerly dominant Arab majority. This dynamic, along with international conservation interests concerned with protecting the island’s rich biodiversity, defined exclusionary land use policies that for years denied local communities benefits from the islands’ forests.[20] However, policy changes in the 1990s, facilitated by strong local political representation, established a new community-based resource management scheme that secured access rights and revenue sharing from a growing tourism industry for Indigenous communities.[20]

Although a similar transition might be envisioned on Socotra, the underlying conditions are not the same. In Socotra, forest resources play a smaller role in local livelihoods and the promise of tourism as an economic driver is more tenuous given the recent security concerns of mainland Yemen. Furthermore, the mainland Yemeni state has acted as an antagonizing force against the racialized Socotri minority, whereas in Tanzania, the mainland ruling party during the described transition shared the same cultural heritage as the Indigenous African population in Zanzibar. I believe a more thorough comparison of these two case studies could provide valuable insights for community-based land management and development prospects on Socotra.

Reflections & Opportunities

Although the Indigenous Socotri people have cultivated sustainable land-use practices for millennia, formalized social forestry is in its infancy on Socotra. In the past, the value placed on forest resources on the island has been modest. However, the opening up of Socotra to the wider world in the last 30 years has exposed the people and landscape of the island to globalizing forces that create new values in old contexts.

Conservationists concerned with global declines in biodiversity have rushed in to study and protect the island’s endemic tree species[13]; the prospect of ecotourism as an economic opportunity has raised the profile of remote landscapes such as the Firmihin forest[10]; and the marginalization of the Socotri people at the hands of the Yemeni state has motivated local pride in the the dragon’s blood tree as a cultural keystone species.[8]

Therefore, as new values for forests emerge in Socotra, it is likely that expanded opportunities for social forestry will arise in the near future. One aspect of this ‘formulation’ stage is to determine the goals of such endeavours in Socotra. Pagdee and colleagues[21][22] describe success in social forestry as multi-dimensional – encompassing ecological sustainability, social equity, and meeting the livelihood needs of local communities. Achieving these wide ranging goals will first require an equitable distribution of the benefits provided by future forest management initiatives.[23] In my reading of the recent socioeconomic history of the island, the major issue has not been an inequitable distribution of benefits, but that there have been relatively few benefits generated by forests to distribute in the first place.

However, as new opportunities for social forestry crop up, distributive justice alone will not be enough to protect natural resources and secure local livelihoods.[23] In this context, political theorist Iris Marion Young emphasizes the importance of not just how benefits are shared, but how decisions are made about those benefits.[24] If distributive justice is concerned with outcomes (who gets what), then procedural justice is focused on process (who decides who gets what). In this respect, there is room for reflection on how well the local Socotri people have been integrated into the decision-making processes that impact their lands and forests. A history of ruling forces that have neglected local communities on the island has resulted in a landscape of disengaged citizens that often lack social and political power.[8] Moving forward, there is therefore an opportunity to enhance procedural justice on behalf of marginalized Socotris. In this vein, the people of Socotra, bolstered by the regional enthusiasm and support of the Arab Spring movement, took a step towards self-determination by pressuring the Yemeni government to make the island its own independent governorate in the early 2010s.[8] Unfortunately, the mainland Houthi coup disrupted this transition in 2014 and a combination of political turmoil, natural disasters (cyclones), and the Covid-19 pandemic, have delayed further progress in recent years.

Looking to the future, perhaps there is a chance to better connect the rich forests and lands of Socotra to the well-being of its people. One significant shift would be to more effectively empower local people to lead the conservation and development initiatives occurring on the island. For many years, outside rules, government agencies, and NGOs have pursued their own priorities on Socotra without sincerely engaging with the values of local communities.[10] As a result, far more time, attention, and resources have been invested into protecting the dragon’s blood tree and other significant biodiversity than into people, culture, and livelihoods. Fortunately, this trend is beginning to change as a new multidisciplinary initiative – the Soqotra Heritage Project – recently documented hundreds of cultural heritage assets that showcase the values of local people, often in association with the natural environment.[25] The resulting database of artefacts, historic locations, and recorded oral traditions will be used to inform future conservation and development priorities for the benefit of people and nature.

In a similar manner, social forestry presents a significant opportunity to merge natural and cultural heritage to the benefit of local communities. As Socotra is faced with increasingly powerful outside influences – including global conservation interests, international markets, regional political powers, and climate change – the self-determination of the Socotri people and the preservation of the island’s unique biodiversity must be prioritized. In summary, the emerging role of social forestry in Socotra offers a promising path towards distributive and procedural justice for local people and the protection and sustainable use of the island’s exceptional forest resources for future generations.

References

- ↑ Taylor, A. (Nov 25, 2013). "The Galapagos of the Indian Ocean". The Atlantic. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2006). Socotra Archipelago: Proposal for inclusion in the World Heritage List (p. 165). UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/document/168954

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Al-Okaishi, A. (2020). "Local management system of dragon's blood tree (Dracaena cinnabari Balf. f.) resin in Firmihin forest, Socotra Island, Yemen". Forests. 11(4): 389. doi:10.3390/f11040389 – via MDPI.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 García, C.; Vasconcelos, R. (2017). "The beauty and the beast: Endemic mutualistic interactions promote community-based conservation on Socotra Island (Yemen)". Journal for Nature Conservation. 35: 20–23. doi:10.3390/su11133557 – via Elsevier ScienceDirect.

- ↑ International Union for Conservation of Nature (2004). "Dragon's Blood Tree". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Maděra, P.; Volařík, D.; Patočka, Z.; Kalivodová, H.; Divín, J.; Rejžek, M.; Vybíral, J.; Lvončík, S.; Jeník, D. "Sustainable Land Use Management Needed to Conserve the Dragon's Blood Tree of Socotra Island, a Vulnerable Endemic Umbrella Species". Sustainability. 11(13): 3557. doi:10.3390/su11133557 – via MDPI.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Van Damme, K.; Banfield, L. (2013). "Past and present human impacts on the biodiversity of Socotra Island (Yemen): implications for future conservation". Zoology in the Middle East. 54(3): 31–88. doi:10.1080/09397140.2011.10648899 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 Elie, S. D. (2020). "State-Community Relations: Political History Conjunctures". A Post-Exotic Anthropology of Soqotra, Volume I. Springer International Publishing. pp. 227–305. ISBN 978-3-030-45638-2.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Peutz, N. (2011). "Bedouin "abjection": World heritage, worldliness, and worthiness at the margins of Arabia". American Ethnologist. 38(2): 338–360. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1425.2011.01310.x – via AnthroSource.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 Forrest, A. (2021a, Nov 10). Personal interview with Dr. Alan Forrest, biodiversity scientist, Centre for Middle Eastern Plants at the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh [video call].

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 Scholte, P.; Al-Okaishi, A.; Suleyman, A. S. (2011). "When conservation precedes development: a case study of the opening up of the Socotra archipelago, Yemen". Oryx. 45(3): 401–410. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1425.2011.01310.x – via Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2003). The Republic of Yemen: Socotra Archipelago Management Plan 2003-2008 (p. 81). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. https://whc.unesco.org/document/168953

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Attorre, F.; Van Damme, K. (2020). "Twenty years of biodiversity research and nature conservation in the Socotra Archipelago (Yemen)". Rendiconti Lincei. Scienze Fische e Naturali. 31: 563–569. doi:10.1007/s12210-020-00941-7 – via SpringerLink.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Attorre, F.; Francesconi, F.; Taleb, N.; Scholte, P.; Ahmed, S.; Alfo, M.; Bruno, F. (2007). "Will dragonblood survive the next period of climate change? Current and future potential distribution of Dracaena cinnabari (Socotra, Yemen)". Biological Conservation. 138(3-4): 430–439. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2007.05.009 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Menzies, N. K. (2007). "Naidu Village, Yunnan Province, China". Our Forest, Your Ecosystem, Their Timber: Communities, Conservation, and the State in Community-Based Forest Management. New York Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press. pp. 17–29. ISBN 9780231510233.

- ↑ MacDicken, K. (2021, Oct 13). Sideshows, priorities and the theatre of the real in international forestry [guest lecture for FRST 522]. University of British Columbia.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Scholte, P., Miller, T., Shamsan, A. R., Suleiman, A. S., Taleb, N., Millory, T., Attorre, F., Porter, R., Carugati, C. & Pella, F. (2008). Goats: part of the problem or the solution to biodiversity conservation on Socotra? [Paper presentation]. IUCN: World Heritage Site evaluation, Socotra, Yemen. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263586501_Goats_part_of_the_problem_or_the_solution_to_biodiversity_conservation_on_Socotra

- ↑ Riggs, R.; Langston, J. D.; Sayer, J.; Sloan, S.; Laurance, W. F. (2020). "Learning from Local Perceptions for Strategic Road Development in Cambodia's Protected Forests". Tropical Conservation Science. 13. doi:10.1177/1940082920903183 – via SAGE Journals.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Elie, S. D. (2020). "Politics of Redistribution: Governance Culture and Public Ethos". A Post-Exotic Anthropology of Soqotra, Volume I. Springer International Publishing. pp. 307–346. ISBN 978-3-030-45638-2.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Menzies, N. K. (2007). "Jozani Forest, Ngezi Forest, and Misali Island, Zanzibar". Our Forest, Your Ecosystem, Their Timber: Communities, Conservation, and the State in Community-Based Forest Management. New York Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press. pp. 30–49. ISBN 9780231510233.

- ↑ Pagdee, A.; Daugherty, P. J. (2006). "What Makes Community Forest Management Successful: A Meta-Study From Community Forests Throughout the World". Society & Natural Resources. 19(1): 33–52. doi:10.1080/08941920500323260 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ↑ Bong, I. W.; Moeliono, M.; Wong, G. Y.; Brockhaus, M. (2019). "What is success? Gaps and trade-offs in assessing the performance of traditional social forestry systems in Indonesia". Forest and Society. 3(1). doi:10.24259/fs.v3i1.5184.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 De Royer, S.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Roshetko, J. M. (2018). "Does community-based forest management in Indonesia devolve social justice or social costs?". International Forestry Review. 20(2): 167–180. doi:10.1505/146554818823767609 – via Ingenta Connect.

- ↑ Young, I. M. (2008). "Justice and the Politics of Difference". The New Social Theory Reader (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 261–269. ISBN 9781003060963.

- ↑ Forrest, A. (2021b). "Soqotra Heritage Project: Building local capacities for the protection of the unique cultural and natural heritage of Socotra". Panorama: Solutions for a Healthy Planet. Retrieved November 8, 2021.