Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/2020/The development and problems of community forestry in Cameroon’s post-colonial era: A case study in Bamenda Highlands region

Abstract

The community forestry mechanism expands the government's role in forestry departments' decision-making at the national level and decentralizes management rights and authority to local communities [1]. Therefore, community forestry management involves the government's overview in planning for the sustainable development of timber resources and non-timber forest products, promoting customary rights and equality of indigenous groups, and facilitating capacity-building with assistance locally and internationally. This study aims to review the experience and potential problems of community forestry development in the Kilum-Ijim Forest Project in Bamenda Highlands, Cameroon. The reflections on the collaboration between the Cameroonian government and local communities should be assessed by examining the community's participation in forest management with conservation results. As a result, the purpose of this research is to report on the long-term local development of community forestry from the Kilum-Ijim Forest Project in 1987 to the present and to generate feasible recommendations and adjustments for future long-term development.

Key words: decentralize; customary rights; collaboration; capacity-building; participation.

Introduction

An overview of community forestry in the Kilum-Ijim Forest

The Kilum-Ijim Forest (Kilum forest and Ijim forest) is the most extensive and highly fragmented forest patches located in the Bamenda Highlands region in the Northwest Province of Cameroon. The remaining forest cover of this area is 20,000 hectares[2]. According to the World Conservation Union (IUCN), 15 montane bird species and more than 40 montane plant species endemic to Cameroon were discovered in the Bamenda Highland[2]. The forest was recognized as one of the essential and rare montane ecosystems with many charismatic species in the world. Moreover, three major indigenous groups (The Oku, Nso, and Kom tribes) and local communities also live around the forests. Their livelihoods largely depend on the forests, as the forests provide water, fuelwood, honey, timber products, and other non-timber forest products with cultural use[2]. Thus, the Kilum-Ijim forests on their ancestral land have important cultural and spiritual values to these residents. In 1987, the Kilum-Ijim Forest Project was established and worked with local communities to prevent further forest loss from the over-farming, grazing, and clear-cutting[2]. According to the development of community forestry (CF) in the Bamenda Highlands, the local community's future goal is to continuously strengthen their forest restoration capacity. To facilitate this sustainable management of forests, the collaboration between local communities, the Ministry of the Environment and Forestry (MINEF, now is MIFOF), and international NGOs are essential for achieving the goals.

Historical timeline of community forestry development in Cameroon [3]

1. From the colonial period (1884-1960) to the beginning of the 1990s, the centralized management of forest resources in Cameroon expropriated control from the local communities, who are excluded from accessing, using and generating economic benefits from such resources [4].

2. 1986: The Kilum-Ijim forest in Bamenda Highland has been reduced 50% of its 1963 area due to agriculture [5].

3. 1987: The Kilum-Ijim forest project was established and has attempted to adopt community forestry approach to stop deforestation[5].

4. 1988: The Tropical Forestry Action Plan (including five national forest policy objectives) developed strategies for the process of forest reformation [3].

5. 1994: New Forestry and Wildlife Law: the Cameroonian government provided framework for the creation of legal claimed community-based forest management (CBFM).

6. 1998: In the national context: The First community forestry management agreement signed in 1998, and the Community Forestry Unit was established at the Ministry of the Environment and Forests (MINEF) in 1999 [3]. In the Kilum-Ijim context: the implementing process of community forestry is slow, and only 4 local communities have officially approved CF management.

7. 2001: “MINEF Decision 518 prioritizing attribution of CF areas to communities (sign on the pre-emption rights)” [3].

8. 2004: The Ministry of the Environment and Forestry (MINEF) committed to analyze and evaluate community forestry simple management plan.

9. 2007: “100th Community forestry management agreements signed”[3].

10. 2010: Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) community forestry certification standard developed.

Tenure arrangements

The Kilum-Ijim forest project is the collaborative management between the local community, traditional authorities, and government. Specifically, the 1994 forestry law granted the access right to the local community. The communities can get their legal status by applying for the community forestry license and signing the Temporary Management Agreement that they committed to the conditions while practicing their use rights and obtaining livelihood without affecting the forest state[6]. Thus, the local villagers can also submit cases concerning their rights to the court, which is the Cameroonian government's judicial branch. However, the Cameroonian government entrusting these rights to local communities in the forest do not comprise ownership rights or alienation rights[7]. Besides, traditional governance systems, such as the autonomy or local ruling system within the ethnic minority groups, are not recognized by the 1994 forestry law. It also means the indigenous people only have customary rights in the community forests and have no legal rights to the ownership of the same forests [4].

| Access rights: | The local community and the indigenous groups can access to the community forestry within the non-permanent forest zone. |

| Use/Withdrawal rights: | The activities for local communities to gather non-timber forest products (NTFP) (e.g.: fuelwood, honey, fruit-picking) for living and spiritual use (e.g.: Sacrifice, traditional medicine) are allowed in the community forests. |

| Management rights: | The local communities are responsible to monitor the timber-harvesting activities and they can apply simple management plans, like deciding the harvesting areas and practicing forest regeneration. |

| Exclusive rights: | The local community can only exclude members of other/adjacent villages from entering or using the local community forest. |

| Market rights: | The local communities could generate income from selling timber and NTFPs harvested in their community forests; they could also promote eco-tourism and management the revenue accruing from ecotourism. |

| Pre-emption rights: | By introducing the pre-emption rights in the 1994 forestry law, the communities can have the priority "in the attribution of community forest areas in the face of competition from sales-of-standing volumes and other classic forest licensing options in the same forests" [3]. |

Notably, as the bundle of rights mentioned in Table 1 was introduced to the local communities by MINEF, the local community can apply for community forest concession from the forestry administration (MINEF). Before applying formally, the community needs to hold a widely publicized consultation meeting. Attendance at the meeting should ensure that representatives deliberate on the issues under consideration, including appointing managers, setting management objectives, and determining the community-managed forest boundary [4]. The completed application will be submitted to “the Divisional Delegate of MINEF and then Provincial Delegate and next to Community Forestry Unit via the Sub-Director for Inventories and Management and then to the Director of Forestry” [4]. Due to the complexity of solving historical problems and investigations by bureaucratic institutions at all levels, the application process is tortuous but long. It is essential to ensure that other forest permits do not restrict the forest concerned; the previous tenurial disputes should be finished through arbitrations to maintain subsequent community forestry practices consistent with forest laws. As a result, the signing of this management agreement is tedious for the community because it must pass through multiple levels of officials in the decision-making process.

Communities that get approval must prepare their first five-year management plans and sign the Temporarily Management Agreement between them and the Forest Department (MINEF). Like the management rights explained in Table 1, local communities have shown an advantage in demonstrating their interest in applying for community forests in any areas designated for logging, ending the competition between logging companies and communities[3]. In addition, the Temporarily Management Agreement signed between the local communities and MINEF for the exploitation in the Kilum-Ijim forest needs to be renewed after every five years, and the local communities can renew their management of a community forest after 25 years at least. The Kilum-Ijim Forest Project still works on community-based forest management up to today.

Institutional/administrative arrangements

The 1994 forestry law divided forests into a permanent zone (forests in this zone are state-owned and managed exclusively) and a non-permanent zone (forests in this zone are state-owned but co-managed with private holders, local communities, or municipalities)[4]. By setting the CF framework in the non-permanent forest estates in the same law, community forestry was managed by the corresponding unit within the MINEF. Specifically, MINEF, now is MINFOF, a national-level government agency in charge of managing all forest and wildlife resources, tenure arrangements, and benefits-sharing from these resources[8]. Moreover, the community forestry department was responsible for facilitating the co-management agreement between the village communities and MINEF on the same non-permanent forest block. Based on the 1995 decree of application, MINEF's community forestry department has oversight of the community forests brought into being by the complementary of 1994 forest law. The decree stipulated that the community forest in non-permanent forest land shall not exceed 5,000 hectares, and the local community shall be entrusted to manage and benefit from it.

The 1998 Manual of Procedures for details stated that the local community needs to be constituted as a legal entity with the appointed manager who shall represent them to negotiate with the government to forward the management agreement’s signing. The manager also has the duty to delineate the map about the community forest area and develop a management plan for the first five years [3]. The management plan provides the assessment of forest resources in the community concerned, the community forests’ development goal and operational instructions, and the local groups’ customary rights (including access, use, management, exclusion, marketing, and pre-emption rights).

At the management level, the Forestry Administration (MINEF) receives technical and financial supports from the international NGOs, and local staff will be sent to each community to implement governance and offer technical supports to these communities. On the other hand, the traditional authorities supervise the management process and pass information between the Forestry department (MINEF) and local villagers (the traditional ruling system is not legalized). Besides, the International NGOs have played leadership and capacity-building role in the Kilum-Ijim Forest Project (and the Bamenda Highlands Forest Project). Birdlife International (BLI) is a non-governmental organization from the United Kingdom responsible for the conservation and development of Kilum-Ijim forests.

The CF's institutional structure in Cameroon set out the decentralized forest management to the local community. It provided opportunities for a complement of networks whose mandate was to pioneer with establishing community forests [4]. Thus, according to the participation of different stakeholders, including the local community, traditional authorities, international NGOs, and government in the Kilum-Ijim forests, " there was a significant complement to this local, regional and international networks operating in Cameroon, which provides considerable scope for cross-scale perspectives and synergies". Specifically, these networks were consisting of different social actors and formed “the general assembly; a steering committee; an executive secretariat; thematic working groups and in-country regional focal points" [4]. From the interview with a researcher in CIFOR, Cameroon: “The network’s identity and autonomy are, however, eroded by its over-reliance on a project (BLI) within the Forest Department and the cooperation between all of these networks was considered poor” [4].

Social Actors

Affected stakeholders: their main relevant objectives, and their relative power.

Affected Stakeholders: Three indigenous tribes; local communities; community forestry entities; local community forestry networks.

- Rightsholders: The three indigenous tribes in Bamenda Highland, their customary rights (access, use and management rights after 1994 Forest Law) were recognized by the Cameroonian government, and also they have their ruling councils on local affairs from time immemorial.

- The Oku and Nso people are using the forest resources in Kilum Forest.

- The Kom people are using the forest resources Ijim Forest.

- Stakeholders: Community forestry entities and local community forestry networks.

- Community forestry entities or local initiative groups (with appointed local managers): They are legal entities constituted on behalf of communities to apply for license/tenure and manage the community[3]. They are also responsible for the management and operation of community-based forest management locally.

- Community Forestry Networks: The roles of community forestry networks are mainly focusing on advocacy and lobbying for the community forestry system, knowledge generation, and capacity building. For example, the Africa Women's Network for Community Management of Forests (REFACOF) worked on gender equality and fight for livelihood issues around community forestry [3].

- User group: Local communities.

- Local Communities (including traditional authority): Local groups live in/near the Kilum-Ijim forests for few generations who demand the community-based forest management system. They are the main users and primary beneficiaries of community forests and community forests' main beneficiaries [3].

Interested stakeholders: their main relevant objectives, and their relative power.

Interested stakeholders: Forestry Department of Cameroon (the Ministry of the Environment and Forestry, now is MINFOF: the Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife); International and Local NGOs; Timber companies; Academia from outside the community.

- International and Local NGOs: In the context of Kilum-Ijim forests in Bamenda Highland, BirdLife International (BLI) is the principal facilitator of community-based forest management's implementation and capacity-builder in this region. Also, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and BirdLife International carried out advocacy work together; Global Environment Facility (GEF) acted as the donor that mobilized tremendous financial capital for community forestry work [3].

- the Ministry of the Environment and Forestry (Now is MINFOF): The government agency is the watcher and rule-maker of community forestry law. It is responsible for decision-making, approval, facilitation, and monitoring. "The Sub-directorate of Community Forestry has a direct responsibility in collaboration with subnational level units at the regional, divisional, and sub-divisional levels" [3].

- Timber Companies: Timber companies can become investors in the community forestry and exploit forest resources through agreements with communities. Sometimes they can educate the locals by learning by doing [4].

- Universities and Consultants: They provide solutions and alternate plans to both government, networks, business, and communities through research as needed. "They also induce knowledge, training to influence thinking through reports/ publications" [3].

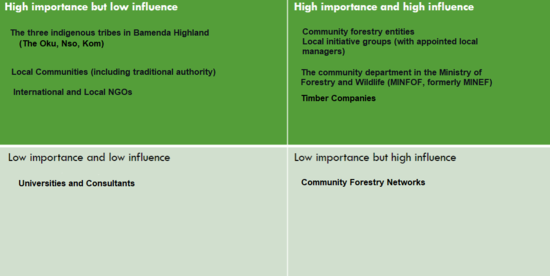

The assessment on power analysis and multi-level governance:

-Local level:

The three indigenous tribes in Bamenda Highland: The Cameroonian government has not legalized the customary land rights of indigenous groups. Therefore, these three indigenous groups have limited rights to access, use and manage the Kilum-Ijim Forest, because they value the ecosystem services and spiritual connections of the Kilum-Ijim Forest. The process of promoting community forestry among indigenous communities has been slow because their attitudes towards community forestry were doubtful.

CF Entities or local initiative groups (with appointed local managers): They represent the local community and negotiate with the Forest Department (MINEF) to sign any agreements and achieve development goals. The appointed local managers are responsible to the administrative management of community forestry.

Local Communities (including traditional authority): All activities in the Kilum-Ijim forest of local communities are under the management and supervision of CF entities and traditional authorities; these two groups are community forestry management partners.

-Municipal level:

Community Forestry Networks: They are local networks and organizations that they could help promote equality and human rights in the local community through lobbying, but they do not have legal enforcement power.

-Federal level:

MINEF(Now is MINFOF): There is the community division unit in MINFOF. They are generally government agencies are legislators, supervisors, decision-makers representing the country, and therefore have the highest authority on the development of community forestry in Cameroon. However, by adding too many governance levels to a topic, they may encounter serious corruption problems.

-International level:

International and Local NGOs: They could give voice to the vulnerable groups and help capacity-building word-widely, but they cannot provide permanent helps to the local groups.

Timber Companies: They represents the power of capital outside the country. Their investment and planning in the Kilum-Ijim forest are driven by economic interests. However, they are also critical drivers of community forestry development by giving incentives and help to the local people. They could interchange open-accessed forest resources to capital assets. The community members can formally conserve forests as people tend to protect capital for future benefits economically[1].

Universities and Consultants: Their roles in research, knowledge exchange, and education are of great significance to the rational development of CBFM globally. However, they cannot directly participate in the actual community forestry management of Kilum-Ijim Forest.

Discussion of the relative successes and failures

The success of the CBFM in the Kilum-Ijim forests:

Since the establishment of community forests in the Kilum-Ijim forests was launched relatively earlier than other cases, the implementation of community-based forest protection has played a role in conserving ecology. Therefore, the Bamenda Highland community forestry is a successful example for building a partnership in the conservation projects, which has reached the original goal and is spreading throughout the region [2]. The aims and intentions of the CBFM system or the achievements have done in the context of the Kilum-Ijim forest project, Bamenda Highland, Cameroon [3]:

- Protecting the fragmented montane ecosystem and recovering biodiversity from responding to environmental change by saving the forestry heritage.

- Granting the access, use, management, exclusion, marketing and pre-emption rights to local communities in the Kilum-Ijim forests.

- Encouraging local participation and recognizing women's participation in forest management and conservation.

- Recognizing more community rights of indigenous groups and local institutions and "legitimizing local knowledge"[6].

- Equitable sharing of forest resource management benefits between the local communities, the Cameroonian government and the timber companies[6].

- Promoting local communities' contribution to national GDP and productivity.

- Ensuring forest regeneration through afforestation.

- Setting an effective enforcement system and institutional framework for revitalizing forestry in Cameroon in the post-colonial era.

The failure of the CBFM in the Kilum-Ijim forests:

My assessment of relative failures in the Kilum-Ijim CBFM system: this approach did not give back much power to local communities to determine the ultimate property rights of the Kilum-Ijim forests, although the three ethnical groups have claimed their ownership of the same forests in the Bamenda Highland from time immemorial. Moreover, the process of implementing a community forestry system was slow and financially expensive for some remote and low-income communities due to the renewal of the management agreement is required in every five years. Some other factors influence the performance of CBFM in the Kilum-Ijim forests, they are[5]:

- MINFOF (formerly MINEF) lacks capacity: The Cameroonian government is a poor democratic institution that has caused severe corruption.

- The lack of trust influenced the collaborative management between governmental agencies, local communities, and traditional authorities. The centralized nature of the administration and authority cannot get support from local initiatives.

- Lack of commitment and consensus on community forestry at the national level.

- There are conflicts between ethnic minorities and between farmers and herders.

- The complexity of stakeholders and the non-homogenous stakeholders resulted in conflicts in community forestry.

In addition, even though the central government of Cameroon have gave the rights of access, use, management, exclusion, marketing and pre-emption rights to local communities in the Kilum-Ijim forests within the non-permanent forest zone, this decentralized forest management is restricted by the limited size of community forest. As the permanent forest block has larger area and has more productive forests with higher timber value, it indicates that the zoning plan has confined the local communities and their rights to a marginalized, less-productive spaces form the perspective of generating household income in the forests [7].

Generally, the Cameroonian government's recognition of the local communities' ownership of forests and autonomy are critical in the next step of political decentralization because the ownership and alienation rights are the most important rights claimed by local communities[7]. Furthermore, provoking the communities' genuine interest in forest conservation and ecosystem restoration can favor community forestry's success in the Bamenda Highlands region[2]. As long as local communities can realize the meaning of long-term sustainable development through education, they will protect the forests and ecosystem for improving communities' self-resilience[2].

Recommendations

A strong institution that is transparent and accountable to its governance can be the foundation to provide the appropriate forest resource policies. The appropriate resource policies should manage all the aspects in natural resource development to avoid corruption, starting from the ownership of forest resources, timber-harvesting, setting up deals with companies, timber export, deciding how to invest the resource revenue and how the resources will be used. Therefore, for the future conservation result, it is needed for Cameroonian government to establish its long-term sustainable development goal including the aspects mentioned based on different local context. To be noticed, inclusive decision-making or multi-stakeholder participation could facilitate legitimacy for the proper marketing rules and resource models. It can also guarantee that policy-making considers the broad range of social values and knowledge[9]. In the perspective of globalization, the extensive communications and information exchange on the development of natural resources are a binding force for sustainable development among different countries and governments. The interactions between countries can help build consensus and reach an agreement on wicked natural resource issues by running various global and regional organizations.

For generating and enhancing community forestry in the Kilum-Ijim forest, Bamenda Highland, Cameroon, we suggest:

- Securing property rights and ownership and decentralizing more control and power over land and forest resources to the ethnical minorities and local communities.

- Giving the incentive to the locals by linking their livelihoods to the results of conservation.

- Promoting the entire community's self-reliance and the long-term prosperity of communities by poverty alleviation.

- Reducing reliance on forests by developing other service sectors.

- Facilitating partnership, networking, and collaborations between community forest and government and between business entities and community forests. (bilateral; multilateral.)

- Encouraging knowledge generation and scientific research on forest management: attempts to increase knowledge sharing between foresters and traditional knowledge experts.

- Improving education, health, road construction, and water supply for local well-being. Increasing investments (both capital and capacity investments) from private enterprises locally and internationally. (e.g., joint venture)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Wily, Alden (2004). "Can we really own the forest? A critical examination of tenure development in community forestry in Africa". International Association for the Study of Common Property (IASCP): 9–13 – via In Tenth Biennial Conference.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Gardner, Anne (2002). "Community forestry in the Bamenda Highlands region of Cameroon: a partnership for conservation" (PDF). Defining the way forward: sustainable livelihoods and forest management through participatory forestry: 18–22 – via In Second International Workshop on Participatory Forestry in Africa.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 Minang, A; Duguma, A; Bernard, F; Foundjem-Tita, D; Tchoundjeu, Z (2019). "Evolution of community forestry in Cameroon" (PDF). Ecology and Society. 24: 1–14.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Mandondo, Alois (2003). "Snapshot views of international community forestry networks: Cameroon country study" (PDF). CIFOR.org. Learning from International Community Forestry Networks – via CIFOR Yaounde.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Penn, J; Gardner, Anne (1999). "Government and non-government institutional collaboration in implementing community forestry: the case of Kilum-Ijim forest project" (PDF). Tree for Life.org: 26–30 – via In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Community Forestry in Africa on the theme: Participatory Forest Management: a strategy for sustainable forest management in Africa.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Buchenrieder, G; Balgah, A (2013). "Sustaining livelihoods around community forests. What is the potential contribution of wildlife domestication?". The Journal of Modern African Studies: 57–84.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Oyono, R (2009). "New niches of community rights to forests in Cameroon: tenure reform, decentralization category or something else". International Journal of Social Forestry. 2: 1–23.

- ↑ REDD (2019). "Ministry of Forests and Wildlife (Cameroon)". The REDD desk – via MINFOF(Cameroon).

- ↑ OECD (2011). "The economic significance of natural resources: key points for reformer in eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia" (PDF). OECD Publication – via Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

| This conservation resource was created by Peiyue Yan. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |