Course:FNH200/Projects/2023/Olestra Regulation

Introduction

Olestra, also known as Olean as its brand name, is a fat substitute accidentally developed by two researchers working under the American company Proctor & Gamble (P&G) while they were researching ways to increase infant fat intake. When P&G originally discovered olestra, they intended to market it as a drug that could reduce cholesterol levels due to the sucrose polyester's ability to bind to fat-soluble molecules. However, olestra was unable to sufficiently lower cholesterol levels by the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) standards, so P&G had to revise their plans. By 1987, the company repetitioned the FDA to allow olestra onto the market as a fat substitute.[1]

Chemical Composition

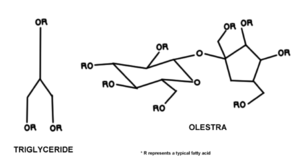

it is an esterified sucrose attached to a maximum of eight fatty acids whereas most conventional fats are triglycerides, with an alcohol or glycerol backbone.[2] The sucrose in Olestra is esterified to be a mixture of octa-, hepta-, and hexaesters. Any other esters are isolated and removed via an acetic-acid methanol wash. The fatty acids of Olestra are long chained. Further preparation is done by altering and refining the substitute in order to remove colour and to ensure that it meets composition requirements as laid out by the fat industry.[3]

It has similar heat stability in comparison to triglycerides with its smoke, flash and fire points being the following approximate values: 480°F, 550°F, and 625°F or 250°C, 288°C and 330°C. Due to their fatty acid composition, Olestra and triglycerides react similarly when undergoing food preparation processes, such as frying, and no significant differences can be perceived in the final product.[3]

Health Effects

Gastrointestinal Effects

Consumption of Olestra commonly leads to digestive issues, as olestra affects the body's ability to absorb fat soluble vitamins. One study found that three grams of olestra caused severe drops in the levels of beta-carotene, which is a common dietary source of vitamin A.[4] Consumers can experience symptoms such as loose stool, abdominal cramping, diarrhea and flatulence. The severity of the symptoms can mild but may also be intense.[5] Olestra was being studied on both human and animal populations. Gastrointestinal is the only area that is affected with olestra, as there was no absorption nor metabolization on this area. Long term studies on animals showed, olestra is non-toxic, not carcinogenic and not mutagenic. However, it was reported that individuals who had high intake of olestra presented with some gastrointestinal symptoms. [6]

Appetite Behaviour

In a study done with rats, Olestra was found to promote weight gain. Due to Olestra having a similar mouthfeel to fat but having no calories, it may disrupt the ability to understand the sensory properties of food and predict the calories, therefore leading to overeating and weight gain within a mixed fat diet. This was shown when the introduction of Olestra caused the animals to not have the ability to perceive fatty foods as high in calories. Rats that were fed a mixed fat diet ended up with more adiposity, weight gain and food intake. However, rats that were fed a fat diet of only Olestra did not experience negative effects on their ability to correlate calories and food properties.[7]

Regulation

United States

In 1987, the Procter and Gamble Company submitted a petition to the FDA, seeking an amendment to the existing regulations governing food additives regarding fat substitutes. This petition aimed to secure authorization for the use of olestra as a viable alternative to conventional fats in food products. The FDA later approved Olestra in savoury snacks for in 1996. Due to Olestra affecting fat soluble vitamin absorption, the FDA requires that products that contain Olestra have those vitamins be added back. The products must also contain a label that warns potential consumers of digestive issue that the Olestra products can cause.[2] However, this labelling requirement has been amended since August 2003 due to an appeal by Procter and Gamble. In the federal ruling, the FDA stated that olestra meets the safety standards as outlined by food regulation guidelines on additives, and that the original labelling requirement was to inform consumers about the potential effects of the fat substitute, not to identify illness or health risks. By the FDA's standards, unlabelled food containing olestra are not considered health risks.[8]

Canada

Olestra was rejected for use in the Canadian food industry in 2000. This is because P&G did not provide sufficient proof that reintroducing vitamins into food products containing olestra was enough to offset the consequence of the consumer's impaired ability to absorb fat soluble vitamins.[9] Since then, no further appeals were made to Health Canada as the company decided to prioritize the American market. In terms of consumer reactions, olestra was met with outcry and mild reactions. Certain nutritional scientists argued that letting a plastic fat (also known as a trans fat) would have negative affects on our food systems. Others say that a small serving of products containing olestra has minimal effects and while consumers could overeat, the messy gastrointestinal consequences can function as a signal to stop eating.[4]

Potential Exam Q

Question 1 is a call back to Lesson 3, and tests us on learning objective "compare and contrast the different types of fat replacers and alternative sweeteners used in foods". Simplesse is a protein-based fat substitute and cannot withstand heat, while Maltrin (maltodextrins) and Olestra have similar burning points at 240°C and 250°C respectively.

Question 2 compares regulation of olestra between the United States and Canada, as its important to have the Canadian viewpoint of what's approved and to be able to contrast that with American regulators.

References

- ↑ "A BRIEF HISTORY OF OLESTRA". Nov 1996. Archived from the original on 5 Dec 2022. Retrieved 4 Aug 2023.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Prince, Diane; Welschenbach, Marilyn (May 1998). "Olestra: A New Food Additive". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 98: 565–595 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Lawson, Kenneth; Middleton, Suzette; Hassall, Christopher (Aug 1997). "Olestra, a Nonabsorbed, Noncaloric Replacement for Dietary Fat: A Review". Drug Metabolism Reviews. 29: 651–703. doi:10.3109/03602539709037594 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Driedger, Sharon (December 16 2013). "Olestra Controversy". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Olestra (olean)". Center for Science in the Public Interest. February 3 2022. Retrieved August 8 2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ Hunt, Zorich, & Thomson., R., N. L., & A. B. (1998). "Overview of olestra: a new fat substitute". Canadian journal of gastroenterology = Journal canadien de gastroenterologie. 12(3): 193–197.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ Swithers, Susan; Ogden, Sean; Davidson, Terry (Aug 1 2012). "Fat substitutes promote weight gain in rats consuming high-fat diets". Behavioural Neuroscience. 125: 512–518 – via PubMed Central. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Food Additives Permitted for Direct Addition to Food for Human Consumption; Olestra, 68 Fed. Reg. 46399 (Aug. 5 2003).

- ↑ "Canadian Food Regulators Give Olestra A Thumbs Down". The Free Library. 2 July 2000. Retrieved August 9 2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)