Course:FNH200/Projects/2022/Natto

Introduction and History

Natto is known as a superfood which originated in Japan. It is typically consumed for breakfast alongside other foods such as steamed rice, miso soup, and pickled vegetables[1]. It is a dish that contains many nutrients and vitamins which results in many health benefits such as stronger bones, healthier heart and immune system, improved digestion, weight loss, improved brain health, and even possible claims made that it reduces the risk of certain cancers[2]. Natto is made of fermented soybeans and its characteristics include having a slimy, sticky, and stringy texture, a pungent smell, and a nutty flavour[3].

Although there is no exact date of when natto was created, it is claimed to have originated between 1051-1083 as it was accidentally discovered in northeast Japan by Minamoto Yoshiie (Hachimantaro)[4]. He was a Minamoto clan samurai during the late Heian period and Chinjufu-shōgun[5] (which is translated as commander-in-chief of the defense of the north[6]). Hachimantaro placed cooked soybeans in a rice-straw sack on the back of his horse and the horse was warm, which allowed the soybeans to ferment, therefore, creating natto. Later in December 19, 1405 the word natto is mentioned by the Kyoto aristocrat Noritoki Fujiwara. He calls it "itohiki daizu" in Japanese, which is translated to stringy soybeans[7].

Microorganisms Involved

The microorganism responsible for the fermentation process which produces natto as we know it is a bacterium called Bacillus subtilis (B. subtilis), originally found in rice straw[8].

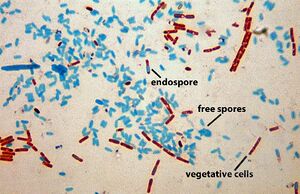

B. subtilis is a gram-positive, rod-shaped, endospore-forming bacterium capable of aerobic respiration and anaerobic fermentation[9]. An image of stained B. subtilis cells can be seen on the right. The specific strain of B. subtilis involved in the production of natto is B. subtilis natto. During the preparation of natto, steamed soybeans are inoculated with spores of B. subtilis natto for approximately 20 hours, during which time the starch and proteins of the soybeans are used as fermentation substrates for B. subtilis to produce a mixture of amino acids, vitamins, and enzymes[8]. At approximately the 15 hour mark in the fermentation process, formation of poly-γ-glutamic acid occurs and natto becomes sticky[8]. Production of poly-γ-glutamic acid results in the formation of a white-coloured slimy mucous substance that coats the beans[10], giving the distinct texture natto is known for. Ultimately, it is through taking advantage of the fermentative metabolism of B. subtilis that we are able to transform regular soybeans into a popular cultural food with high nutritive value.

Processing and Fermentation

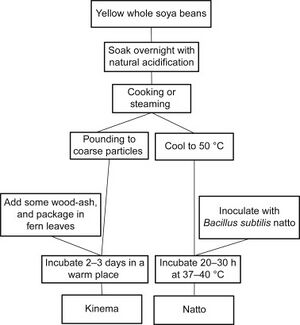

The processing of natto can be broken down into four essential steps: preparation, inoculation, incubation, and finishing. [11] A summary flowchart of this process can be viewed here and to the right. [11] The preparation phase consists of soaking whole soya beans at a temperature of 21-23°C for 20 hours.[11] This soaking process causes the beans to roughly double in size and ensures that the soybeans are soft enough for the next stage of steaming. [12] Afterwards, the beans are drained and steamed at 121°C in a large pressure cooker for 40 minutes. Steaming kills the bacteria that may be on the surface of the soybeans and allows for the enzymes that will eventually be produced to penetrate into the soybeans and work better.[13] The soybeans are then cooled to about 50°C, which allows for inoculation to occur [14]. A pure culture of B. subtilis natto spores is added, which germinate very well at this temperature.[11] The soya beans are then distributed into small containers and incubated which involves covering them and keeping them at a constant temperature of 50°C for 1-3 days. [11] It is during this time that the bacteria multiply significantly to roughly 109–1010 colony forming units (cfu) per gram. [11] After this time, the beans will have been covered with its characteristic white-coloured sticky coating, indicating that it is ready. [15] For better quality and taste, the package may be kept in the refrigerator for 1-2 days to allow for maturation and is then removed for either consumption or retail sale at supermarkets. [15] Maturation is usually done at a low temperature of 5°C or less, which prevents the natto from continuing to grow during the packaging and shipping process.[13]

Packaging and Storage

Commercial natto and homemade natto are packaged differently. Commercial natto that can be bought in Asian grocery stores is normally packaged and sealed in a white plastic foam box, and the inside is covered with a thin layer of clear plastic. Commercial natto is often sold in a set that contains two or more boxes of natto, and the outside strip seal is labeled with nutrition facts and the expiry date. Homemade natto is packaged in covered containers to maintain the proper cultured environment of natto, and it is necessary to cover natto with a food cloth on top of the container to keep its moisture level[16].

There are two ways to store natto. The first way is to store it in the refrigerator, and the temperature should be set between 0 - 4°C, which can last up to 7 days[17]. The other way is to store natto in the freezer, and set the temperature to about -18°C, which allows it to last about a year[17]. In Japan, because natto is a staple food that is very popular and quickly sold in grocery stores, natto is typically stored in the refrigerator while in the West, due to the longer turnaround time for natto to be sold, it is kept in the freezer [18]. Natto becomes spoiled and is not suitable to eat when it grows small white dots[16]. The reason that natto lasts a lot shorter in the refrigerator than in the freezer is that natto will continue to ferment slowly in the refrigerator[16].

Potential Exam Question

Question: What microorganism is involved in the production of natto and through which process does it do so?

a) Bacillus subtilis; anaerobic metabolism

b) Bacillus subtilis; aerobic metabolism

c) Lactobacillus bacteria; aerobic metabolism

d) Yeast; anaerobic metabolism

Answer: a) Bacillus subtilis; anaerobic metabolism

As mentioned above, Bacillus subtilis natto is the specific strain that is involved in the fermentation of natto. Fermentation does not require oxygen. Therefore, it is a form of anaerobic metabolism.

Explanation as to why you should know about this: We learned about fermentation and biotechnology in Lesson 9 and the role that microorganisms play in creating certain foods. Natto is a unique food that relies on the fermentation process of bacteria, which is a relevant topic in our FNH 200 course.

References

- ↑ "Natto: Japanese History of a Modern-Day Superfood". NYrture.

- ↑ Petre, Alina (March 31 2017). "Why Natto Is Super Healthy and Nutritious". healthline. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Petre, Alina (March 31, 2017). "Why Natto Is Super Healthy and Nutritious". healthline.

- ↑ William & Akiko, Shurtleff & Aoyagi (February 15 2012). "History of Natto and Its Relatives (1405-2012)". Soyinfo Center. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Minamoto no Yoshiie". Wikipedia.

- ↑ "Chinju-fu Shogun (Commander-in-Chief of the Defense of the North) (鎮守府将軍)". Japanese Wiki Corpus.

- ↑ William & Akiko, Shurtleff & Aoyagi (February 15 2012). "History of Natto and Its Relatives (1405-2012)". Soyinfo Center. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "Traditional healthful fermented products of Japan".

- ↑ "Regulation of the Anaerobic Metabolism in Bacillus subtilis". line feed character in

|title=at position 28 (help) - ↑ "Texture modification of soy-based products".

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Nout, R (2015). "18 - Quality, safety, biofunctionality and fermentation control in soya". Advances in Fermented Foods and Beverages: 409–434 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ↑ USAGJapan. "Process of making Natto". YouTube.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "How Natto is Made".

- ↑ Wei, Qun; Chang, Sam K.C. (December 2004). "Characteristics of Fermented Natto Products as Affected by Soybean Cultivars". Journal of Food Processing and Preservation. 28: 251–273 – via Institute of Food Science & Technology.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Liu, KeShun (2008). "14 - Food Use of Whole Soybeans". Soybeans: 441–481 – via Elsevier ScienceDirect.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Frey, Malia (2021-01-03). "Natto Nutrition Facts and Health Benefits". Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 CFH Admin (2022-06-23). "Natto FAQS". Cultures for Health.

- ↑ "Natto (Japanese Fermented Soybeans)".