Course:CONS200/2023WT2/The ongoing debate on trophy hunting: Does it help conserve elephants?

Introduction

Human-elephant conflict is a major conservation concern in elephant-range countries such as Africa and Asia. Many conflicts have arisen between humans and elephants, and are usually caused by economic benefits, resource competition and land allocation [1]. Although a variety of management strategies have been developed, trophy hunting has long been a controversial form of conservation [2]. Trophy hunting is a form of hunting wild animals for sport, “in order to display part or all of their bodies as trophies” [3]. Here, we review current human-elephant conflict management strategies and discuss both short and long-term solutions of species coexistence. Moreover, can recreational hunting be used as a tool for conservation, or is it only a threat to biodiversity? Could other methods of managing elephant-human conflicts have better effects on both humans and elephants? If so, what are they, and how might they differ?

Historical Context and Background on Hunting

The Concept of Trophy Hunting

Trophy hunting is a multinational, multimillion-dollar industry practiced throughout the world , with 107 countries exporting trophies and 104 countries importing them [4]. It is broadly defined as the shooting of carefully selected animals - frequently big game animals such as African and Asian elephants-under official government license for the purpose of collecting trophies such as tusks and skulls for display.

A Brief History of Trophy Hunting in Africa

Trophy hunting as we understand it today can be traced back to the late 19th century with the colonization of African nations. Colonists exploited the riches of nature and the wildlife within it at astounding rates, with the most significant natural resource being ivory-coming from elephant tusks. Ivory was not only used for medications and ornaments, but also as a symbol of wealth in many Victorian-era homes [5]. Through exportation of ivory, colonists' economies thrived, which encouraged further penetration of Africa’s natural resources.

There was such a demand for ivory that one African port alone demanded “the slaughter of 25,000 [elephants]” [6] to meet the desire for ivory products. However, many hunters were indiscriminate in their choice of elephants to kill-young, old, male or female, it did not matter, as the primary purpose was to sell ivory. Their slaughter culminated in the 1980s with an exponential rise in demand for ivory. Research shows in 1979, the African elephant population was estimated to be around 1.3 million, but by only 1989, 600,000 remained [2]. As can be seen from Africa’s colonial history, trophy hunting, in its nature, is about power.

The Controversy of Trophy Hunting for Conservation

Many conflicts have arisen between humans and elephants, and although a variety of management strategies have been developed, trophy hunting has long been a controversial form of conservation. Trophy hunting generates controversy due to its potential costs and benefits to conservation, ethical considerations, and its contribution to local economies in range states.

Contribution to High Extinction Rates

Trophy hunting can have a direct impact on driving species to extinction. By targeting animals with the largest tusks and other prized features, research has found, trophy hunting can “lead to extinction” [7] by removing the fittest genes in populations trying to adapt to already increasing environmental pressures. Not only are species driven to extinction, but trophy hunting can disrupt population demographics, age structures, sex ratios and social structures [8]. The psychological effects on elephants who’ve witnessed their family members’ deaths are also being underestimated. This often causes them to become aggressive towards other animals, humans, or themselves. It should also be noted that trophies are mostly aimed at high-quality males for their impressive size and striking secondary features. Lead researcher Dr Rob Knell, from Queen Mary University of London, said

“This demonstration that trophy hunting can potentially push otherwise resilient populations to extinction when the environment changes is concerning. Because these high-quality males with large secondary sexual traits tend to father a high proportion of the offspring, their ‘good genes’ can spread rapidly, so populations of strongly sexually selected animals can adapt quickly to new environments. Removing these males reverses this effect and could have serious and unintended consequences.

“We found that ‘selective harvest’ has little effect when the environment is relatively constant, but environmental change is now a dangerous reality across the globe for considerable numbers of species.” [7]

“Removing those males is not a good idea”, Knell said, as it “makes it more difficult for their populations to adapt to ecological disruptions over the following generations.” [7]. The risk is even greater in regions with poor wildlife management, such as Africa, where many species are already being pushed closer to extinction through human-wildlife conflict and poaching.

Where Does The Money Go?

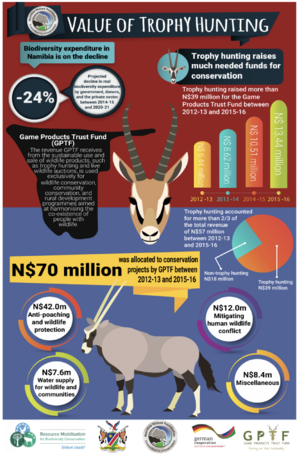

The money from trophy hunting does not make it to local communities but to the hands of a few individuals or governments. Research shows that funds made through trophy hunting that reach local range communities are diminutive and rarely benefit adequately from such activities. Inequitable distribution of hunting revenue is one of the main problems with this form of conservation. A 2013 study by Economists at Large, states that “only three percent of revenue made by trophy hunting makes it to local communities for welfare, education, and other community-based programs” [9]. The majority of funds goes in the pockets of trophy hunting outfitters and to governments. This has widely been acknowledged through both traditional and social media to discredit the validity of trophy hunting as a tool for wildlife conservation and rural development. Another report taken in 2017 by Economists at Large says that “trophy hunting amounted to less than one percept of tourism revenue in eight African countries [10] . Thus demonstrating that trophy hunting does little for conservation efforts. Additionally, National Geographic published a report in 2015 mentioning that moving funds from hunting to conservation can be fraught with mismanagement, and how government corruption, particularly in Zimbabwe under President Robert Mugabe’s rule, prevents elephant hunting fees from going towards any conservation efforts [10].

Promoting alternative approaches and economic development

Funding

One of the leading reasons for trophy hunting is the generated revenue that is earned from hunters who pay thousands of dollars to have a permit for Hunting. In some governments especially in developing countries where habitat protection and management is limited due to financial issues, one way of providing conservation funding is allowing hunters to shoot down a variety of species including rare ones like elephants. AWF supports projects to mitigate human and animal conflicts, it includes supporting programs to ensure human-wildlife coexistence and implementing strategies and ideas to benefit communities while protecting wildlife. Kaddu Sebunya, AWF President, said, “It is a call to the conservation community, institutions, and governments to increase investment in alternative financing to support programs such as relocation, eco-tourism development, and securing space for these species to thrive.” AWF supports projects to mitigate human and animal conflicts, it includes supporting programs to ensure human-wildlife coexistence and implementing strategies and ideas to benefit communities while protecting wildlife. [11]

Balancing wildlife population

In some cases, trophy hunting can be seen as a tool for wildlife population management, particularly when certain species become overabundant and pose a threat to other species. By culling to harvest individuals with certain conditions we can maintain the sustainability of the ecosystem. However, conservation can be achieved through non-lethal and ethical practices. Fertility-controlling programs are a means of managing the population of species. It may involve sterilization and contraception. This method is particularly effective for species with well-defined social structures and less dispersal.[12]

Managing threatening species

Species management is an incentive for trophy haunting, the idea is that some individuals in some species can become a threat to the survival of the rest of the group, and in that scenario, the animal should be killed. In 2014, Namibia’s government organized an auction for a hunter to kill a black rhinoceros. Black rhinos may be critically endangered, but the male in question has passed the breeding age and posed a danger to other rhinos, and the proceeds went to support rhino conservation.[13] In fact, there are other means to address this issue, which can be useful for problematic elephants as well. Translocation can be one of the solutions, by capturing the rhino and relocating it to a different location where it is less likely to pose a threat to rhinos or humans. Assessing and managing the habitat may be helpful as well, by investigating the reasons behind the aggression of the animal like the lack of resources such as water and food, or the competition over land. To address these difficulties the first step is stopping the regression of their habitat.[14]

Economic impact

According to evidence, the community and conservation benefits of trophy hunting are exaggerated. However, according to a report published in 2017 that studied the contribution of trophy hunting to the economy of 8 sub-Saharan countries, only 1.9% of the total US$17 billion in tourism revenues, and only 0.76% of a total of 2.6 million jobs in wildlife tourism in these countries were generated by trophy hunting. On the other hand, the generated revenue from activities like photo tourism has exceeded the income of trophy hunting.[15]There are numerous ways to support the local economy instead of resorting to the act of hunting. In the areas where wildlife exists, there must be rich nature, which is an attractive destination for tourists interested in sightseeing intact nature. Also, governments of these countries with such unique nature and wildlife should facilitate residents to hold their cultural festivals and events that showcase their local traditions, music, dance, and cuisine. Efforts should be put into action to familiarize tourists from all around the world with the rich culture of these areas. Developing the tourism industry is not only a significant progress towards economic growth but also will contribute to fostering cultural exchange.

Human-wildlife conflict

In some regions, where humans and animals coexist, due to the increase in human population, and growing villages, boundaries have been eliminated and consequently, human-wildlife interactions have converted to even fatal conflicts. The damage can be done to properties like livestock and crops or physical such as injury or even the death of one side. One study about the prevalence of wildlife damage to households reported that 73% had experienced crop loss within the previous year, and 30% had endured the loss of animals over the same period. Several solutions have been found to be effective in mitigating the degree of loss including electrical fences, night watching, fencing, lighting, and guard animals. However, only the use of physical structures seemed to have a more significant effect, which requires governmental funding and the cooperation of non-benefit organizations to establish these structures, otherwise, usually, local people can’t afford the cost construction of these structures and start retaliating against wild animals by killing them.[16]

By addressing the underlying drivers of trophy hunting and promoting alternative approaches to wildlife conservation and economic development, it is possible to prevent trophy hunting while respecting cultural traditions and fostering sustainable livelihoods for communities. Cooperation and a commitment to conservation are key to achieving lasting change.

Current Usage and Other Means of Conservation

Although Trophy Hunting is controversial as a principle of conservation, it has achieved significant effects in several countries in Africa. In Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia, and Tanzania, elephants are one of Trophy Hunting's targets, and there has been a significant increase in elephant population under this measure[17]. These countries are all managed by governments or government agencies working in collaboration with local communities to carry out Community-Based Trophy Hunting (CBTH) [17], but the specific application methods vary; Namibia can be shown as one of a successful sample of employing community-based trophy hunting.

Namibia:

Current Situation of TH:

Namibia has always been regarded as a successful case in Community Based Trophy Hunting (CBTH). Due to the popularity of ivory in the market and the tradition of hunting that exists in both Namibia's traditional society and colonial history, since the early 1990s, CBTH has developed into a complete tourism industry in the area[18]; until 2011, CBTH brought an average annual income of 3,000,0000 USD to Namibia[19]. According to former Namibian Minister of Environment and Tourism, trophy hunting had become one of the most important industries in Namibia due to its strong contribution to local communities’ economic growth, employment, training opportunities and well-being[18]; the theory behind the dynamic benefit of CBTH is that it empowerments local communities in various aspects.

Theory of CBTH being successful- Empowerment Theory:

CBTH is believed to have promoted trust between the community and the government by supporting the empowerment of local communities, thereby consolidating cooperation between the two parties. The empowerments include:

- Economic empowerment: Equal share of the revenue from CBTH between communities and the improvement of facilities by that revenue[20]. Unlike traditional protected areas, a larger proportion of CBTH revenue will be equally distributed to surrounding communities, which can directly improve the quality of life of residents.

- Psychological empowerment: The pride of community members in their culture and natural resources[20]. In Namibia, hunting is part of their tradition on their traditional land, and now it is being appreciated by all incoming hunters.

- Social empowerment: Enhanced social cohesion and improvement of social problems[20]. The benefits that CBTH brings to local communities improve residents’ distrust of conservation measures that bring inconvenience and the government. At the same time, the equal distribution of income encouraged by CBTH mitigates the problem of inequality in the communities.

The empowerments introduce motivation for community members to conserve targeted animals, including elephants since the empowerments could not happen without their work in conserving targeted animals, including elephants, and increasing their population to allow sustainable hunting[18]. Local communities' help is critical because they usually do better than the government in conserving local wildlife because these communities are closer to the wildlife, giving them the incomparable advantage in observing, tracing and reporting the wildlife[19].

Other Means of Conservation:

Namibia has adopted traditional conservation measures in their history, such as in 1907, Etosha National Park was established under the plan by the central government. Etosha National Park is known as "Namibia's greatest wildlife sanctuary" [21], and it is one of Namibia's very important tourist attractions. The economic and ecological benefits that Etosha National Park has brought to Namibia are considerable, but the relationship between it and local communities has been a problem. Haillom used to live on the land where Etosha National Park as hunter-gatherers centuries ago[22], but were evicted during colonial times; when they tried to return in the 1980s, they were told that their land was protected and their use of the resource had been prohibited by law [22]. Moreover, the tourism revenue brought by Etosha National Park is also considered to be of no significant help to surrounding communities; according to a 2010 survey of local villagers, 88% believed that Etosha National Park has never brought them any benefit[22]. The isolation of Indigenous people and the lack of benefits to surrounding villages cause conflict between them and the government and until now, Halliom has not reached a consensus with the Namibian government regarding the resettlement of Halliom[21]. This example illustrates one limit of traditional conservation methods in Namibia: The unpaired power and interests between the government and residents[19]. Now, Namibia uses CBTH as a method of ecological tourism alternative to traditional protection measures [17].

Analysis of effects of different mitigation techniques on both humans and elephants

One of the largest threats to elephant populations is human-elephant conflict[23]. Many of these conflicts stem from elephants conducting “raids” on crop farms and destroying property. In response, there often are retaliatory elephant killings, which does not line up with current conservation efforts. These conflicts cause a loss of support from affected local peoples towards conservation efforts[24]. Because of this, many mitigation techniques are used in order to reduce these conflicts, which help keep elephant populations from needing to be culled, and keep people safe.

The Chilli Method

A study involving the use of “chilli-briquettes”, which are briquettes made with dry chilli, elephant feces and water, found that they were a good repellent of elephants[25]. Before the briquettes were used, elephants in the studied area moved during the night. However, once the briquettes were introduced and burned at night the elephants' pattern changed to day time. This change in behavior makes it easier for farmers to guard against the elephants, as people are more active during the day. The study concluded that it is a good short term repellent, but not a long-term solution[25].

The Guard Tower Method

A study conducted by Gunaryadi et al.[26] focused on other repelling techniques, such as setting up guard towers, fences, and a trip-wire system. These trip-wires were made with cans and stones which would produce loud noises to let guards know where exactly the elephants were coming from, as an early warning system [26]. This study wanted to see if additional support to villages would get them to adopt these practices even after the study was concluded. In the first stage of the study, villagers were provided food and funds for crop guards, materials for building watchtowers, batteries for radios and other devices, and more. Then, in a second stage, they pulled back on some of the support, to see if the villagers would continue the practices now seeing the benefits. The study has shown that these methods can have a relatively high success rate at preventing these raids[26]. For example, one village was able to repel 91.2% of the elephant raids. Once the villagers saw the successes stemming from these methods, they voluntarily adopted these crop defense tactics, even once support from the research group was fully withdrawn. Furthermore, the villagers concluded that they could now plant “high risk” crops, crops that elephants are particularly fond of and target.

Why use other methods?

It is important that we gauge the effects of trophy hunting versus other elephant mitigation methods. These mitigation methods are effective, although they cause stress to the elephants in the short term by being driven away, it reduces the number of retaliatory killings, elephants needing to be removed from the wild, or elephants being culled via trophy hunting[26]. We can use these methods as pre-cautions, and if needed, use trophy hunting if things escalate.

Conclusion

Although trophy hunting[3] has been in practice with the late 19th century, it remains a controversial subject to this day[2]. Weighing the benefits of this multi-million-dollar industry against its environmental and human impacts is a difficult undertaking[4]. It its infancy trophy hunting was conducted to meet the considerable demand for ivory[6]. Here is where the general slaughter of all types of elephants was pervasive. More recently trophy hunting is argued to be a contributor to conservation efforts, due to the large funds that hunters will pay for a hunting permit, although many sources state otherwise[9][10]. It can also be argued that it aids in managing individuals that are perceived threats to their population, although there have been alternative solutions proposed on how to remove these particular elephants. Other means of conservation have been suggested, such as the case studies in Namibia for their Community Based Trophy Hunting[20]. This method has credited to help empower local peoples economically, psychologically, and socially, whereas trophy hunting has been criticized for not necessarily helping locals directly. Other smaller-scale methods such as the Chilli[23] and Guard Tower[26] methods can be seen as preliminary suggestions in avoiding the Human-Elephant conflict that often lends itself to trophy hunting as a remedy.

References

- ↑ Chen, Windy; Gallagher, Alli; Yu, Jiaxin; Xu, Shuyue. "Can China's Ivory Trade Ban Save Elephants?". Retrieved 04-12-2024. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Dickson, Barney; Hutton, Jonathan; Adams, William A. (2009 Feb 10). [www.wiley.com/en-us/Recreational+Hunting,+Conservation+and+Rural+Livelihoods:+Science+and+Practice-p-9781444303179. "Recreational Hunting, Conservation and Rural Livelihoods: Science and Practice"] Check

|url=value (help). Wiley. Retrieved 2024-04-12. Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 ""Trophy Hunting (Noun) Definition and Synonyms: Macmillan Dictionary." TROPHY HUNTING (Noun) Definition and Synonyms | Macmillan Dictionary".

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Sheikh, Pervaze A (March 20, 2019). ""Trophy Hunting In Southeast Asia"".

- ↑ Larson, Elaine. "The History of the Ivory Trade". National Geographic. pp. (38).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Bird, Megan. "Stolen Trophies: Hunting in Africa Perpetuates Neo-Colonial Attitudes and is an Ineffective Conservation Tool" (PDF).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Knell, Robert J.; Martínez-Ruiz, Carlos (November 29, 2017). "Selective harvest focused on sexual signal traits can lead to extinction under directional environmental change". Retrieved 04-12-2024. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Mysterud, A. (February 21, 2012). "Trophy hunting with uncertain role for population dynamics and extinction of ungulates".

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Campbell, Roderick (2013). "How Much Does Trophy Hunting Really Contribute To African Communities?" (PDF). p. (9).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Cruise, Adam (November 17, 2015). "Is Trophy Hunting Helping Save African Elephants?". National Geographic. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- ↑ "Trophy hunting not an option to finance conservation in Africa". African Wildlife foundation. 2017.

- ↑ Massei, Giovanna (2023). "Fertility Control for Wildlife: A European Perspective". MDPI.

- ↑ Ham, Anthony (Nov 25, 2021). "Conservation Issues That Won't Go Away". Round Trip.

- ↑ "International Rhino Foundation". ASAP.

- ↑ "For a revision of the trophy hunting regime in the European Union" (PDF). Bornfree. October 2022. pp. 5–6. line feed character in

|title=at position 29 (help) - ↑ "Lessening Human-Wildlife Conflict And Improving Conservation". Faunalytics. October 4, 2016.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Ullah, Inayat; Kim, Dong-Young (Autumn 2020). "A Model of Collaborative Governance for Community-based Trophy-Hunting Programs in Developing Countries". Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation. 18(3): pp.145-160.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Koot, Stasja (Feb 2018). "The Limits of Economic Benefits: Adding Social Affordances to the Analysis of Trophy Hunting of the Khwe and Ju/'hoansi in Namibian Community-Based Natural Resource Management". Society & Natural Resources. 32(4): pp.417-433.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Palazy, L.; Bonenfant, C.; Caillard, J.M.; Courchamp, F. (July 2011). "Rarity, trophy hunting and ungulates". Animal Conservation. 15(1): pp. 4-11.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Thomsena, Jennifer; Lendelvo, Selma; Coe, Katherine; Rispel, Melanie (Jan 2020). "Community perspectives of empowerment from trophy hunting tourism in Namibia's Bwabwata National Park". Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 30(1): pp. 223-239.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Dieckmann, Ute (August 2023). "Thinking with relations in nature conservation? A case study of the Etosha National Park and Haiǁom". Journal of The Royal Anthropological Institute. 29(4): pp. 859-879.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Hoole, Arthur (August 2010). "Place-power-prognosis: Community-based conservation, partnerships, and ecotourism enterprises in Namibia". International Jornal of the Commons. 4(1): pp. 78-99.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Elephant". World Wildlife. 2024 Feb 05. Retrieved 2024 April 12. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ Nyhus, P; Tilson, R; Sumianto (2009). "Crop-raiding elephants and conservation implications at Way Kambas National Park, Sumatra, Indonesia". Oryx. 34( 4): 262–274 – via CamdridgeCore.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Pozo, R; Coulson, T; McCulloch, G (2019). "Chilli-briquettes modify the temporal behaviour of elephants, but not their numbers". Oryx. 53 (1): 100–108 – via CambridgeCore.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 Gunaryadi, D; Sugiyo; Hedges, S (2017 May 16). "Community-based human-elephant conflict mitigation: The value of an evidence-based approach in promoting the uptake of effective methods". PLoS One. 12 (5) – via PLos ONE. Check date values in:

|date=(help)

| This conservation resource was created by Course:CONS200. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |