Course:CONS200/2023/The invasion of possum as a threat to New Zealand’s natural environment

Introduction

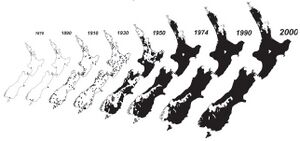

Since its introduction, the common brushtail possums population in New Zealand (NZ) has gone from only a few hundred in the 1850's to over 70 million in one century[1]. Brushtail possums pose a serious threat to NZ’s native flora and fauns by destroying plants and birds’ nests, eating birds’ eggs and invertebrates, and competing with other species for food[1]. As well, brushtail possums carry diseases, such as bovine tuberculosis[2], which they spread to other animals and plants. The common brushtail possum has been labelled a ‘pest’[3] in New Zealand and there are extensive trapping and extermination mechanisms[1] in place in attempts to deescalate the threat they post to the economy, cattle and dairy agriculture, and to endangered endemic flora and fauna[4]. The New Zealand government has taken several remedial actions to control the population and mitigate their negative effects, however there are ethical considerations to be taken into account when considering these methods as solutions.

Background

The common brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula[5]) is a nocturnal, semi-arboreal marsupial native to Australia and naturalized in new Zealand[6]. The common brushtail possum is mainly a folivore (herbivore that specializes in eating leaves[7]) but are also omnivorous as they have been known to eat small birds and eggs[1]. The main groups of flora consumed are grass and forbs (flowering, non-grassy herbaceous plants[8]), native browse (woody leaves and stems), and woody fruit[4]. As with most marsupials, the female brush tailed possums have a pouch where a single offspring develops and remains for months after birth[4]. It has a prehensile bushy tail that is adapted to grasping branches, and its fur colour varies from silver-grey, brown, and gold[5].The common brushtail possum is the most widespread marsupial[9] in New Zealand, since its introduction in 1850s by European settlers to establish a fur industry[3]. They are primarily forest dwellers, but can be found in other habitats, such as agriculture land and urban areas[6]. In New Zealand, the common brushtail possum has few threats (humans and cats[5]), making it more densely populated in NZ than in its native Australia where it has numerous threats (foxes, goannas, carpet snakes, powerful owls[5])[1].

Nature of the Issue: Impacts on ecosystem, consequences, and potential benefits

In the New Zealand ecosphere, the brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula) is deemed an invasive species due to its contributions to deforestation[10] and arboreal mortality[11], as well as its predation[12] of and competition[13] with native fauna. Additionally, possums are a notable wildlife host of bovine tuberculosis[14] and, while cattle are nonnative species in New Zealand, they are an important contributor to New Zealand’s GDP, accounting for almost 2% of the national household income[14].

Forest Degradation and Arboreal Mortality

The introduced brushtail possum is a certain contributor to the degradation of New Zealand’s forests. In areas without any form of possum population control measures in place, the cumulative percentage of trees dead after six years was slightly greater than 11%[11]. While data for New Zealand's natural (prior to the introduction of possums and other similar invasive species) arboreal mortality rates are difficult to come by, the effectiveness of a one-hit control measure to diminish the possum population has proved to be effective, providing “strong evidence that possum browse resulted in elevated tree mortality at many of the study sites, and that a modest level of possum control was sufficient to reverse much of that impact”[11]. When considering that a ‘modest level’ of population control was enough to decrease arboreal mortality rates by a quarter or at times even a third, it is indisputable that the brushtail possum has heavily contributed to deforestation and environmental degradation through raising the arboreal mortality rate[10]. When analyzing the trees which saw no browsing via possum, the observed annual mortality rate was around 1%, compared to the average, which was around double at slightly over 2%[11].

Forest Composition

In addition to general deforestation and raising arboreal mortality, possum populations have altered the compositional makeup of New Zealand Forests[10]. Some endemic species such as Silver Beech (Nothofagus menziesii) and Pigeonwood (Hedycarya arborea) are left largely untouched and thus unaffected by the invasive possums[11], seeing less than 1% annual mortality[11]. However, many other endemic species are at a much greater risk due to preferences in possum browsing habits[10]. One such species is Haumakaroa (Raukaua simplex), a small evergreen tree endemic to New Zealand’s lowland forests. In 2010, browse was observed on 97% of Haumakaroa trees, with a 6% annual mortality rate recorded[11]. Smaller trees are disproportionately affected by possum browse[15], which both affects the composition of many forests[10] and slows the process of ecological succession[11], slowing the reforestation of New Zealand forests[15].

Yet, smaller trees are not the extent of the brushtail possum’s effect on altering forest composition through their browsing and consumption preferences. Fruiting trees such as the nikau palm (Rhopalostylis sapida), a species endemic to mainland New Zealand, are often favorites of the brushtail possum[16]. These trees are often ravaged by possums before being able to produce fruit, as possums usually destroy the nikau palm’s inflorescences entirely, by either chewing through the base or devouring the flower bearing branches entirely[16]. This has dramatic results on the palm’s ability to produce ripe fruit. While 88% of the nikau palms observed in 1985 were able to flower, only 12% were able to produce at least a single ripe fruit[16]. The inability of many trees like the nikau palm to fruit successfully due to possum consumption can affect the plant's ability to reproduce[11], as the seeds within the fruit are the primary method the nikau palm utilizes to sire the following generation. This lack of fruit also forces many species which traditionally rely on the fruit from the nikau palm as a dietary staple to find other sources of nutrition[13].

Interactions with Endemic Species

Other than environmental damage, the brushtail possum is often able to outcompete many species endemic to New Zealand[12]. One such species is the North Island Kokako (Callaeas wilsoni), a bird which was classified as endangered during the 1980s and 1990s[17]. The possum’s diet contains heavy overlap with that of the kokako, notably the dicotyledonous tree and shrub categories of flora[13]. Possums often feed in the forest canopy[10], directly competing with the kokako[17] as well as many other endemic bird species[13]. Possums are also well known to have a preference for the consumption of fruits, which is a staple of the North Island Kokako’s diet[13][16]. Even with increased competition for the dietary keystones such as fruits, both the possum and the kokako[17] are able to substitute with alternative sources of nutrition. However, as evidenced by the possum and kokako’s respective population trends[13], the possum is much more of a generalist and is better suited to a varied diet[10] when compared to the kokako[13]. This lack of reliance on specialized sources of nutrition allows the brushtail possum to outcompete many endemic species such as the north island kokako[13], many of which are rendered endangered or even extinct[17].

In addition to competition, the brushtail possum’s predation of several endemic species is a reason as to why they are classified as invasive to New Zealand[12]. Possums are omnivorous, and thus are known to consume several invertebrate species such as stick bugs, wetas, cicadas, and beetles[12]. The invertebrate species at greatest risk is Powelliphanta, a large, nocturnal, carnivorous species of snail endemic to New Zealand, whose shells are easily chewed through by possums[12]. Furthermore, possums are known to prey on the eggs[17] and chicks[12] of several bird species native to New Zealand, including kokako, brown kiwi, kahu (Circus approximans), fantail (Rhipidura fuliginosa), N.I. saddleback (Philesturnus carunculatus rufusater) and kereru/kukupa (Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae)[12]. The extent to the brushtail possum’s predation of these other species is largely unknown[12], as the consumption of these invertebrate and avian species is viewed as largely opportunistic[12] due to possums being mainly herbivorous[15].

Current Remedial Actions Potential Solutions

Primary methods of common brushtail possum population control include a variety of lethal traps and toxins in ground-based and aerial forms[18]. Most common toxins include sodium monofluoroacetate[19], known as compound 1080, sodium nitrite[18], and brodifacoum[20]. Possum control led by the Department of Conservation (DoC), TBFree New Zealand, and Animal Health Board (AHB)[21]. Additional efforts are done by regional councils, conservation groups, and private landowners[21]. It is often executed in a close proximity to farmlands[18]. Both aerial and ground-based chemical treatments pose a risk of secondary poisonings of wildlife and farmland animals[18]. Non-targeted species may consume the toxins off of possum carcasses, while aerial pesticides may contaminate water reservoirs[18]. Pests of the island country such as black rats, stoats, and feral cats have also been affected by the aerial chemical treatments[18]. To address the concerns raised by local populations over animal welfare and decrease the harmful environmental consequences posed by chemical pesticides, research continues to develop fertility control agents and vertebrate toxic agents that possess low risk to wildlife and farmland species.

Pesticide 1080, the common name of sodium monofluoroacetate, is New Zealand’s most commonly and cost-effective pesticide for possum control[19]. Historically, pesticide 1080 has been spread aerially over large and steep terrains[19]. The pesticide is mixed with carrot and cereal bait attractive to the common brushtail possums[22]. Control methods may look like a single, intense widespread case of poisoning followed by a less extreme ground control, or as a case of poisoning with a subsequent trapping of the possums[23].

A sodium nitrite paste, known as Bait-Rite paste, is a registered Vertebrate Toxic Agent used for possum control in New Zealand[18]. Sodium nitrite is an inorganic salt and a common food preservative that in high doses becomes toxic as it causes disruption of oxygen transport in the circulatory system[18]. It acts as a red blood toxicant causing lethargy, irregular breathing, chocolate-coloured blood, and loss of consciousness in possums[18]. It is an extremely bitter substance and is thus mixed into palatable to possums bait, creating the sodium nitrite paste[18]. Compared to pesticide 1080 and brodifacoum, sodium nitrite paste invokes a faster death rate in possums[18].

Brodifacoum is a slow acting vertebrate toxic agent that bears low risk to humans and domestic animals[24]. It however poses a secondary and tertiary risks to scavengers and predators, as it persists in the common brushtail possum’s livers in high concentrations[24].

Alternative, less popular methods of chemical pest controls are cholecalciferol and encapsulated cyanide baits[20]. Potential methods such as usage of electric shock on possums have been proposed but found to be unacceptable due to animal cruelty[25].

Common brushtail possum population management targets the control of endemic bovine tuberculosis spread by the marsupials. The spread of the bovine tuberculosis may be prevented as long as the diseased possum population does not exceed the infection persistence threshold and if the rate of the possum immigration is 2% or less of the overall population per year[23]. Complete eradication of the disease is not feasible as long as immigration of the diseased possums occurs[23].

Ethical Considerations Regarding the Trapping/Killing of Possums as a Means for 'Pest' Control

Are the methods of killing the possums humane?

Possums are often killed in low-cost ways which are considered unethical. The methods used to kill possums include trapping, clubbing, or relocation. However, the most common approach is the use of poisons such as pesticide 1080 and brodifacoum as they are a cost efficient and “simple” solution. New Zealand’s vision is to have a Predator Free 2050, and they hope to reach this goal with the use of these two slow-acting poisons[26]. Many environmentalists have expressed concern over the use of poison, stating that it is neither a compassionate nor ethical way to eradicate the possum populations.

Jane Wright, previous commissioner for the environment of New Zealand, voiced concern that the use of 1080 is an inhumane and evil way of killing the possums. She argues that there are more compassionate, more humane ways to solve the invasive possum problem in New Zealand than killing possums using these painful methods[26]. Doctor Jane Goodall has also suggested that the current methods used to eradicate the possums are devastatingly cruel. Goodall explains that the poisons used result in extremely long and painful deaths for the possums[27].

The use of budget poisons that result in horrible deaths are clearly not an ethical way to deal with the exponentially growing possum population. Conservationists highlight a wider focus for conserving New Zealand’s biodiversity. Rather than looking for a quick solution (such as the use of these poisons), conservationists such as Wright and Goodall suggest that New Zealand can switch to an alternative approach that is gradual and less cruel to the marsupials.

The influence of using poison on other animals within the ecosystem

The use of poisons such as pesticide 1080 and brodifacoum are not only harmful to possums but also other, non-targeted animals within the environment[27]. Animals such as birds, dogs, farm animals, and deer are unintended victims killed alongside possums. When people carelessly set out poison near their houses or in their neighborhood, dogs and deer frequently fall victim to it as well as the possums[26]. Random poisoning causes significant harm or death to animals that are not supposed to be poisoned. The manner in which these possums are killed negatively influences other animals in the ecosystem and results in long and painful deaths for both the possums and nontargeted animals. When 1080 is ingested, it creates extreme prolonged suffering for the animal which eats it[26]. The use of this poison is not only completely unethical; it is also highly disturbing.

Are New Zealanders against possum killing?

Residents of New Zealand have a very biased and one-sided perspective on the possum population. There is little remorse for possum deaths and the New Zealand government even encourages people to help in the trapping and killing process[26]. Schools hold events and competitions that encourage the killing of possums. From a young age, New Zealanders are desensitized to killing these possums and are taught that they are merely rodents. The acknowledgement that possums are intelligent, sentient beings is neglected in the curriculum of these schools and is ignored by the entire population.

There are few New Zealanders who experience remorse over mass murdering of the possums. It is difficult to find organizations and resources which encourage people to show more empathy and concern for the possums. However, there are two key organizations which demonstrate sensitivity for the possum population: The Jane Goodall Institute and the Science Learning Hub[26]. The Jane Goodall Institute has published studies that highlight the affects and ethics of the possum infestation and some opinions from accredited conservationists. The Science Learning Hub, an online resource for scientific information based in New Zealand, shares many articles and studies which outline alternative solutions for the possum issue, including vaccines to control the population, and traps that are not harmful[26].

A dramatic shift in the perspectives of the New Zealanders can be seen when they are made aware of the effects of the poisons used to kill the possums. A survey published by James Russell in the Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand shows that perspectives towards the use of poisons to eradicate animals has shifted dramatically since 1992. A survey was conducted with 3000 New Zealanders and there was a 9% increase, resulting in nearly half of the population being against the use of poisons such as pesticide 1080 and brodifacoum[28]. The New Zealand population is beginning to shift to the use of less harmful methods to reduce the number of possums, rather than relying on poison.

Conclusion

As a non-native, invasive species to New Zealand, brushtail possums pose a serious threat to the endemic flora and fauna found on the islands. The historical context of the introduction of brushtail possums to New Zealand is rooted in the development of a fur-trade for economic gain. Thus, the negative effects possums have created is an anthropogenic issue which requires an anthropogenic solution. Humans must take responsibility for this in a way that does not cause further harm to the environment. The most impactful and ethical way to stop the further degradation of native flora and fauna would be to trap the possums using non-lethal methods. A shift to non-lethal trapping is increasing in New Zealand, and it would be in the best interest of New Zealanders to adopt these more humane methods. Additionally, trapping can be done by civilians on their property, by parks services in vast landscapes, and in private parks and reserves, making this a solution accessible for a large number of users. The anthropogenic solution of trapping with cheap poison can no longer be tolerated, more humane and non-lethal methods of trapping need to be implemented so humans are not inflicting more environmental harm than they already have.

References

Please use the Wikipedia reference style. Provide a citation for every sentence, statement, thought, or bit of data not your own, giving the author, year, AND page. For dictionary references for English-language terms, I strongly recommend you use the Oxford English Dictionary. You can reference foreign-language sources but please also provide translations into English in the reference list.

Note: Before writing your wiki article on the UBC Wiki, it may be helpful to review the tips in Wikipedia: Writing better articles.[29]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 "Possum facts and control tips". Predator Free NZ. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ↑ Warburton, B; Livingstone, P (March 12, 2015). "Managing and eradicating wildlife tuberculosis in New Zealand". New Zealand Veterinary Journal. 63: 77–88 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Klotz, Hattie (March 8, 2001). "Fur fashion to the rescue: Trapping eases New Zealand's plague of possums". The Ottowa Citizen. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Montague, T (2000). The Brushtail Possum: Biology, Impact and Management of an Introduced Marsupial. New Zealand: Manaaki Whenua Press. pp. 92–104. ISBN 978-0-47-809336-0.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 "Common brushtail possum". Wikipedia. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Northland Pest Control Guidelines" (PDF). Kiwi Coast. 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ↑ "Folivore". Wikipedia. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ↑ Wragg, Peter (March 24, 2018). "Forbs, grasses, and grassland fire behaviour". Journal of Ecology. 106: 1983–2001 – via British Ecological Society.

- ↑ "Marsupial". Wikipedia. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 Efford; Cowan (2004). "Long term population trend of the common brushtail possum Trichosurus vulpecula in the Orongorongo Valley, New Zealand" (PDF). The Biology of Australian Possums and Gliders: 14.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 Nugent; Whitford; Sweetapple; Duncan; Holland (July 2010). "Effect of one-hit control on the density of possums (Trichosurus vulpecula) and their impacts on native forest" (PDF). New Zealand Department of Conservation: Science for Conservation. 304: 68. line feed character in

|title=at position 26 (help) - ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 Innes, John (November 1994). "THE IMPACTS OF POSSUMS ON NATIVE FAUNA". Proceedings of a Workshop on Possums as Conservation Pests. Possum and Bovine TB Control NSS Committee: 12–16.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 Leathwick, J; Hay, Rod; Fitzgerald, Alice (January 1983). "The influence of browsing by introduced mammals on the decline of North Island kokako". New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 6: 18 – via Research Gate.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Ramsey, David; Efford, Murray (August 2010). "Management of bovine tuberculosis in brushtail possums in New Zealand: predictions

from a spatially explicit individual-based model". Journal of Applied Ecology. 47: 911–919 – via British Ecological Society. line feed character in

|title=at position 83 (help) - ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Glen, Alistair; Byrom, Andrea; Pech, Roger; Cruz, Jennyffer; Schwab, Astrid; Sweetapple, Peter; Yockney, Ivor; Nugent, Graham; Coleman, Morgan (September 2011). "Ecology of brushtail possums in a New Zealand dryland ecosystem" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 36: 9.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Cowan (1991). "Effects of introduced Australian brushtail possums

(Trichosurus vulpecula) on the fruiting of the endemic New Zealand nikau palm (Rhopalostylis

sapida)". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 29: 91–93. line feed character in

|title=at position 51 (help) - ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Innes, John; Flux, Ian (1999). "North Island kokako recovery plan" (PDF). THREATENED SPECIES RECOVERY PLAN. 30: 35. line feed character in

|title=at position 29 (help) - ↑ 18.00 18.01 18.02 18.03 18.04 18.05 18.06 18.07 18.08 18.09 18.10 Shapiro, Lee. "Encapsulated sodium nitrite as a new toxicant for possum control in New Zealand". New Zealand journal of ecology. 40 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Bidwell, Susan. "Place invaders: Identity, place attachment and possum control in the south island west coast of new zealand". New Zealand geographer. 71 – via Wiley Online Library.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Earson, Charles. "Alternatives to brodifacoum and 1080 for possum and rodent control-how and why?". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 37 – via Taylor&Francis Online.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Jones, Christopher. [Serving two masters: Reconciling economic and biodiversity outcomes of brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula) fur harvest in an indigenous New Zealand forest "Serving two masters: Reconciling economic and biodiversity outcomes of brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula) fur harvest in an indigenous New Zealand forest"] Check

|url=value (help). Biological conservation. 153 – via Science Direct. - ↑ Powlesland, R.G. "Effects of an aerial 1080 possum poison operation using carrot baits on invertebrates in artificial refuges at whirinaki forest park, 1999–2002". New Zealand journal of ecology. 29 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Barlow, N.D. "Control of endemic bovine tb in new zealand possum populations: Results from a simple model". The Journal of applied ecology. 28 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Meenken, D. "Brodifacoum residues in possums (trichosurus vulpecula) after baiting with brodifacoum cereal bait". New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 23 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Dix, G.I. "The potential of electric shock for the humane trapping of brushtail possums, trichosurus vulpecula". Wildlife Research (East Melbourne). 21 – via Science Citation Index Expanded

Scopus. line feed character in

|via=at position 32 (help) - ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 26.5 26.6 Margodt, Koen (2022). "The Ethical Cost of Predator Free New Zealand 2050". Suffering in the name of conservation – via Jane Goodall Institute.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Goodall, J., T. Maynard, G. Hudson. (2009). Hope for Animals and Their World: How Endangered Species are Being Rescued from the Brink. Grand Central Publishing.

- ↑ Russel, J., Innes, J., Brown, P. (2014). "Predator-free New Zealand: Conservation Country". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 65: 520–525.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ En.wikipedia.org. (2018). Writing better articles. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Writing_better_articles [Accessed 18 Jan. 2018].

| This conservation resource was created by Course:CONS200. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |