Course:CONS200/2021/Steelhead Conservation in British Columbia: Conservation status

Populations of steelhead trout have been facing rapid declines within British Columbia[1]. This is attributable to the increasingly worsening habitat conditions in both marine and freshwater environments[2]. Two vital steelhead habitats within British Columbia include the Thompson River and the Chilcotin River, both of which are freshwater reserves[3]. In the past 15 years, steelhead have been reported to have faced an 80% decrease in population with the Thompson and Chilcotin rivers[4]. The BC provincial government has made efforts to reduce the rate of the declining populations. Their goal is to ensure that the abundance of wild steelhead populations remain at levels that will provide societal benefits for current and future generations of British Columbia[5]. Their objectives to accomplish this goal are twofold: 1) Maintain a diversity of sustainable recreational angling opportunities for steelhead in British Columbia[6]; and 2) Maintain, protect and restore the productive capacity of the freshwater environment to produce steelhead[7].

Trends in Population

Recent History

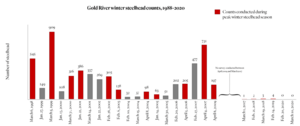

Over the past century there has been an increasing decline in the population size of Steelhead trout in British Columbia. Rivers across the province that have been crucial spawning grounds are depleting at an increasing rate[3]. Referring to figure one, on Vancouver Island, Gold River recorded 731 steelhead trout at peak times during the winter season in 2007. Since then, Counts Recorded between March of 2017 and March of 2020 have not come above 4 steelhead trout with a mean of 0 for Gold River[8]. “It’s an all-time low,” -Eric Taylor, a quantitative biologist at the University of B.C. “You’ve got an entire run depending on the spawning success of just a few individuals. That’s how entire species of animals go extinct”[9]. In southern BC, the Thompson and the Chilcotin Rivers, a record low in population has been reached, dating back to when the records began in 1978[3]. The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada decided that both populations are at risk of extinction. Recommending that they be put in an emergency listing order under the federal Species at Risk Act[10]. This drop in population is not a unique trait of select rivers in BC. Across the North American west coast, the impact has been felt and since 2006 the US Endangered Species Act has covered numerous populations of Steelhead Trout.[11]

Measuring Populations

Changes in populations are divided individually by river, as Steelhead will naturally return to their spawning ground from the ocean.[12] CpAD (Catch per angler day) is an index of abundance based on licensed anglers. In a study done by Barry D. Smith, you can see that the populations seem to spike irradicably year to year when measured year by CpAD. Although population trends using this method seem to be arbitrary, the numbers are reinforced by similar trends yielded by both fishery-dependent and fishery-independent data.[13]

Lifecycle

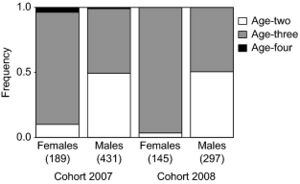

Numbers year to year also vary due to Steelheads’ complex lifecycle. In their life, steelheads return to the river to reproduce where they spawned after living in freshwater. Figure two shows data from a study done by Alicia Abadía-Cardoso documenting the ages of returning fish to the Warm Springs Hatchery and the Coyote Valley Fish Facility in 2007 and 2008. In these two cohorts, most of the Steelheads were either two or three years old, but they can return after anywhere from 1-7 years in freshwater.[12] Steelheads are also known to be iteroparous, they can mate up to three times if they live that long although most do not.[14] This varied life cycle makes it hard to track exact populations. Figure 2 reflects stats from the annual survey, led by the British Columbia Conservation Foundation this graph perfectly depicts just how volatile steelhead numbers can be. In February of 2004, Gold River recorded a local minimum of 32 steelheads but just 3 years later in April of 2007, that number spiked up to 731. Displaying the difficulty in catching downward population trends early on.

Climate Change

Growth in Steelhead Trout has been proven to be vital in their fitness.[15] Body size affects a range of different fitness components including ontogenetic status, life-history strategies, and survival of an individual. The growth rate of salmonids can be directly (and indirectly) affected by water temperature.[16] This direct impact is due to temperature being a regulating factor in and organisms energy output and intake.[17] Since the 1950s the surface temperature in BC waters has been steadily increasing, with both ocean and river waters seeing a rise on average between 0.5-1.5 degrees Celsius depending on location.[18] This could be pointing to a greater overall downward trend in the Trout population looking past recent near extinction.

Modern Conservation Practices

Broad Strategies

The Provincial Framework for Steelhead in BC currently has nine broad strategies set in place to combat the conservation concerns regarding steelhead trout:

- Implement an abundance-based management framework with zones that identify stock status, level of uncertainty, and associated management actions[7].

- Invoke a precautionary policy where a population falls below a lower threshold of 100 adults[19].

- Manage wild steelhead freshwater recreational fisheries to minimize mortality and maximize angler opportunity[20].

- Implement restrictions as necessary to administer wild stock fisheries in a careful and responsible manner[21].

- Encourage ongoing improvements in salmon harvesting and management to reduce steelhead by-catch mortality in commercial salmon fisheries[22].

- Employ hatchery programs to increase angler opportunities where the risks to wild steelhead are low and the expected societal benefits are high[23].

- Manage angler use to maintain exceptional fisheries on Classified Waters[24].

- Incorporate a precautionary approach into management to address environmental uncertainty[25].

- Address key anthropogenic factors that threaten or seriously impact steelhead productivity in freshwater habitats[26].

Current Projects:

The provincial government of British Columbia is currently supporting two major project initiatives specifically designed to minimize steelhead mortalities[27].

The first project is a selective fishing initiative, which utilizes fish wheels, weirs and pound nets to selectively target steelhead[28]. The primary objectives were to: 1) deploy and operate 3 fishwheels within the lower Fraser River, and 2) sample fishwheel catches to provide data[29]. The total project costs amounted to $249,000[30].

The second project emphasized fish passage and monitoring by improving passages within the Bonaparte fishway to provide steelhead access to the upstream spawning habitat[31]. The primary objectives were to: 1) allow spawner abundance, productivity and status monitoring of steelhead, 2) monitor, repair and maintain fish pathways, and 3) monitor and maintain electronic resistivity counters[32]. The total project costs amounted to $1,292,000[33].

Additionally, there exists several projects that are designed to aid salmon conservation in BC, yet also implicitly assist with steelhead conservation:

I. Innovative habitat restoration demonstration

This project, led by the British Columbia Conservation Foundation, is a multi-year, watershed-scale demonstration which incorporates innovative habitat restoration methods that adapts to the recent ecosystem changes, and benefits chinook, coho, sockeye and steelhead[34]. The total allocated funds for the project was $4,952,373[35].

II. BC Fish passage restoration initiative

This project, led by the Canadian Wildlife Federation, will focus on bringing together partners, including federal and provincial governments, NGOs, First Nations and other communities to prioritize fish passage remediation efforts in BC to maximize the efficiency of steelhead trout and pacific salmon fishing[36]. The total allocated funds for the project was $3,999,721[37].

Flaws Concerning Steelhead Conservation

Government Control

The B.C wildlife Federation (BCWF) has recently uncovered troubling news about two steelhead runs located in the Thompson River and the Chilcotin watershed. Findings show net fisheries have been estimating an approximate population decline of eighty percent in returning Steelhead over the past fifteen years.[38] It took the B.C Wildlife Federation almost two years to gain access to the 2800-page document that revealed the unsettling truth about the Steelhead population. Once they had access to the documents, they found hundreds of pages to be redacted; therefore, the BCWF has concluded that the government has been undermining the process for years.[39] In October of 2018, the DFO assistant Deputy Minister’s Office gave notice to the Thompson River and Chilcotin managers to modify some key points related to allowable harm to the Steelhead.[40] According to the BCWF science team, low numbers and decreasing escape trends for both the Thompson and Chilcotin River Steelhead populations will cause harm and will prevent the natural reproduction process.[41] Concluding that the lowest possible allowable harm practices are to be followed at this time. Even though new rules are being set to reduce population decline of the Steelhead population, past trends show that the DFO has religiously maintained status quo[42]. Moreover, since the Steelhead population is near extinction, it is becoming increasingly important to inflict strict punishments for companies who insist to continue their current practices. While these new preventative measures are beginning to take place to protect the population and natural habitats of the Steelheads, the Thompson River and Chilcotin River watersheds are the two most significant examples of why the Steelhead population is near extinction in B.C.

Bycatch

Bycatch has been reported as the main contributing factor to the Steelhead’s population decline.[43] With the help of the science team at the B.C Wildlife Federation (BCWF), a joint research paper was developed to portray the potential recovery of the Steelhead population in B.C.[44] However, when the government drafted the final advisory report for the watersheds, they did not reflect the original recommendations and consensus in the research paper.[45] Bycatch is one of the few variables that is not controllable when it comes to Steelhead conservation due to the accidental nature of it. Since bycatch is also the largest contributing factor to the population decline,[46] these findings specifically apply to net-based fisheries, such as the Thompson River and the Chilcotin Watershed. The steelhead population is listed as an endangered species and the route issues of the main flaws stem from the federal government. The problem is that the federal government routinely withholds information regarding the protection of endangered fish.[47] Regarding Steelhead, the federal government withheld the information that was initially presented to them by the University of Victoria’s Environmental law center and failed to present the actual findings to the public.[48] The government feels a resolution to the problem is ultimately meaningless given the Steelhead population has little to no benefit to the ecosystem.[49]

Why is Steelhead Conservation Important?

Steelhead trout conservation in BC is vital if we want to keep our ecosystems healthy and thriving. Unfortunately, steelhead populations are dwindling rapidly and in Gold River, on Vancouver Island, the populations are at an all time low [8]. Thompson river and Chilcotin steelhead populations have seen the rates of decline over three generations at 79% and 81%, respectively[50] . With this being said, it is clear that now more than ever steelhead populations need to be protected; but why are these fish so essential to ecosystems? Steelhead trout are an indicator species, meaning that they are a good way to judge the health of aquatic ecosystems as a whole as they “use all portions of a river system and require cool, clean water”[51]. Additionally, they are a source of food for a lot of BC’s fauna including sea otters, bears and many species of birds. This means that their extinction could lead to a bottom up trophic cascade forcing their predators to turn to other food sources sending ripples through the ecosystem. In an opposite fashion, the extinction of steelhead trout would lead to their prey no longer having a predator. This could lead to many of their prey such as “mayflies, caddis flies and black flies”[52] no longer having to deal with a key predator potentially leading to overpopulation of these species once again sending a ripple through the ecosystem. Steelhead trout are also an important food source to BC First Nations with the Wet’suwet’en First Nations saying that they “considered steelhead their most important food source” [53]. Steelhead trout are also essential to nutrient cycling in ecosystems. Nitrogen and phosphorus are two nutrients that are critical to the productivity of plants in an ecosystem. Steelhead contribute greatly to the cycling of these nutrients because they store a large amount of them in their tissue, “transport nutrients farther than other aquatic animals and excrete nutrients in dissolved forms that are readily available to primary producers” [54]. Seeing as fish play such a key role in this cycling of nitrogen and phosphorus, fish extinction can have serious negative impacts on ecosystem health as a whole. As one can see, not only do steelhead trout play an essential role in the ecosystems they are a part of, but their health indicates the health of their surrounding environment and they are extremely important to the First Nations people of BC. With all of these factors taken into account, it is essential that this species is protected and steps are taken to conserve the populations that still remain.

References

- ↑ Neilson, John (February, 2018). "Technical Summaries and Supporting Information for Emergency Assessments - Steelhead Trout" (PDF). Sara Registry. p. 2. line feed character in

|title=at position 48 (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ Neilson, John (February, 2018). "Technical Summaries and Supporting Information for Emergency Assessments - Steelhead Trout" (PDF). Sara Registry. p. 2. line feed character in

|title=at position 48 (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Neilson, John. "Technical Summaries and Supporting Information for Emergency Assessments - Steelhead Trout" (PDF). Sara Registry. p. 3. line feed character in

|title=at position 48 (help) - ↑ "BCWF Investigation Reveals Flawed Process for Steelhead". BC Wildlife Foundation. May 2021. line feed character in

|title=at position 47 (help) - ↑ "Provincial Framework for Steelhead Management in British Columbia" (PDF). Fish and Wildlife Branch: 4. April 2016 – via Ministry of Forests, Lands, and Natural Resource Operations.

- ↑ "Provincial Framework for Steelhead Management in British Columbia" (PDF). Fish and Wildlife Branch: 4. April 2016 – via Ministry of Forests, Lands, and Natural Resource Operations.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Provincial Framework for Steelhead Management in British Columbia" (PDF). Fish and Wildlife Branch: 9. April 2016 – via Ministry of Forests, Lands, and Natural Resource Operations.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Wood, Stephanie (November 26, 2020). "A lost run': Logging and climate change decimate steelhead in B.C. river". The Narwhal.

- ↑ Grochowski, Sarah (08/13/2021). "Imminent extinction of Interior steelhead runs foretells what's to come for Fraser River salmon: experts". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 12/06/2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ "Emergency Assessment concludes that BC's Interior Steelhead Trout at risk of extinction". Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. February 2018. Retrieved 12/06/2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Steelhead Trout". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 12/06/2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 12.0 12.1 Fulton, Aaron (06/15/4004). "A review of the characteristics, habitat requirements, and ecology of the Anadromous Steelhead Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in the Skeena Basin" (PDF). Retrieved 12/06/2021. line feed character in

|title=at position 70 (help); Check date values in:|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ Smith, Barry (1999). "Assessment of Wild Steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Abundance Trends in British Columbia (1967/68-1995/96) using the Steelhead Harvest Questionnaire". Fisheries Management Report. No. 110 – via Province of British Columbia Ministry of Fisheries.

- ↑ Peggy Busby, Thomas Wainwright, Gregory Bryant, Lisa Lierheimer, Robin Waples, F. William Wakinittz, Ima Lagomarsino (August 1996). "Status Review of West Coast Steelhead from Washington, Idaho, Oregon, and California" (PDF). noaa.gov. Retrieved 12/10/2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Andre´M. De Roos, Lennart Persson, Edward McCauley (2003). "The influence of size-dependent life-history traits on the structure and dynamics of populations and communities". onlinelibrary.wiley.com. Retrieved 12/10/2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ L. Blair Holtby, Bruce C. Andersen, and Ronald K. Kadowaki (November 1990). "Size-Biased Survival in Steelhead Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss): Back-Calculated Lengths from Adults' Scales Compared to Migrating Smolts at the Keogh River, British Columbia". Canadian Science Publishing. Retrieved 12/10/2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Brett, John (February 1971). "Energetic Responses of Salmon to Temperature. A Study of Some Thermal Relations in the Physiology and Freshwater Ecology of Sockeye Salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka)". American Zoologist. 11: 99–113 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ "Change in Sea Surface Temperature in B.C. (1935-2014)". Environmental Reporting BC. Updated January 2017. Retrieved 12/10/2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ "Provincial Framework for Steelhead Management in British Columbia" (PDF). Fish and Wildlife Branch: 10. April 2016 – via Ministry of Forests, Lands, and Natural Resource Operations.

- ↑ "Provincial Framework for Steelhead Management in British Columbia" (PDF). Fish and Wildlife Branch: 10. April 2016 – via Ministry of Forests, Lands, and Natural Resource Operations.

- ↑ "Provincial Framework for Steelhead Management in British Columbia" (PDF). Fish and Wildlife Branch: 12. April 2016 – via Ministry of Forests, Lands, and Natural Resource Operations.

- ↑ "Provincial Framework for Steelhead Management in British Columbia" (PDF). Fish and Wildlife Branch: 12. April 2016 – via Ministry of Forests, Lands, and Natural Resource Operations.

- ↑ "Provincial Framework for Steelhead Management in British Columbia" (PDF). Fish and Wildlife Branch: 14. April 2016 – via Ministry of Forests, Lands, and Natural Resource Operations.

- ↑ "Provincial Framework for Steelhead Management in British Columbia" (PDF). Fish and Wildlife Branch: 14. April 2016 – via Ministry of Forests, Lands, and Natural Resource Operations.

- ↑ "Provincial Framework for Steelhead Management in British Columbia" (PDF). Fish and Wildlife Branch: 15. April 2016 – via Ministry of Forests, Lands, and Natural Resource Operations.

- ↑ "Provincial Framework for Steelhead Management in British Columbia" (PDF). Fish and Wildlife Branch: 15. April 2016 – via Ministry of Forests, Lands, and Natural Resource Operations.

- ↑ Fish and Aquatic Habitat Branch (2021, August). Interior Frasier Steelhead BC Action plan and Activities Report. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/plants-animals-and-ecosystems/fish-fish-habitat/fishery-resources/interior-fraser-steelhead/interior_fraser_steelhead_bc_action_plan_and_activities_report_august_2021.pdf

- ↑ Fish and Aquatic Habitat Branch (2021, August). Interior Frasier Steelhead BC Action plan and Activities Report. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/plants-animals-and-ecosystems/fish-fish-habitat/fishery-resources/interior-fraser-steelhead/interior_fraser_steelhead_bc_action_plan_and_activities_report_august_2021.pdf

- ↑ Fish and Aquatic Habitat Branch (2021, August). Interior Frasier Steelhead BC Action plan and Activities Report. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/plants-animals-and-ecosystems/fish-fish-habitat/fishery-resources/interior-fraser-steelhead/interior_fraser_steelhead_bc_action_plan_and_activities_report_august_2021.pdf

- ↑ Fish and Aquatic Habitat Branch (2021, August). Interior Frasier Steelhead BC Action plan and Activities Report. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/plants-animals-and-ecosystems/fish-fish-habitat/fishery-resources/interior-fraser-steelhead/interior_fraser_steelhead_bc_action_plan_and_activities_report_august_2021.pdf

- ↑ Fish and Aquatic Habitat Branch (2021, August). Interior Frasier Steelhead BC Action plan and Activities Report. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/plants-animals-and-ecosystems/fish-fish-habitat/fishery-resources/interior-fraser-steelhead/interior_fraser_steelhead_bc_action_plan_and_activities_report_august_2021.pdf

- ↑ Fish and Aquatic Habitat Branch (2021, August). Interior Frasier Steelhead BC Action plan and Activities Report. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/plants-animals-and-ecosystems/fish-fish-habitat/fishery-resources/interior-fraser-steelhead/interior_fraser_steelhead_bc_action_plan_and_activities_report_august_2021.pdf

- ↑ Fish and Aquatic Habitat Branch (2021, August). Interior Frasier Steelhead BC Action plan and Activities Report. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/plants-animals-and-ecosystems/fish-fish-habitat/fishery-resources/interior-fraser-steelhead/interior_fraser_steelhead_bc_action_plan_and_activities_report_august_2021.pdf

- ↑ Forest Enhancement Society of British Columbia (2021, July). $9.3 Million for Wildlife, Fish and Habitat Including Steelhead in Southern B.C. https://www.fesbc.ca/9-3-million-for-wildlife-fish-and-habitat-including-steelhead-in-southern-b-c/.

- ↑ Forest Enhancement Society of British Columbia (2021, July). $9.3 Million for Wildlife, Fish and Habitat Including Steelhead in Southern B.C. https://www.fesbc.ca/9-3-million-for-wildlife-fish-and-habitat-including-steelhead-in-southern-b-c/.

- ↑ Forest Enhancement Society of British Columbia (2021, July). $9.3 Million for Wildlife, Fish and Habitat Including Steelhead in Southern B.C. https://www.fesbc.ca/9-3-million-for-wildlife-fish-and-habitat-including-steelhead-in-southern-b-c/.

- ↑ Forest Enhancement Society of British Columbia (2021, July). $9.3 Million for Wildlife, Fish and Habitat Including Steelhead in Southern B.C. https://www.fesbc.ca/9-3-million-for-wildlife-fish-and-habitat-including-steelhead-in-southern-b-c/.

- ↑ BC Wildlife Foundation (2021, May). BCWF Investigation Reveals Flawed Process for Steelhead. Retrieved from https://bcwf.bc.ca/bcwf-investigation-reveals-flawed -process-for-steelhead/.

- ↑ BC Wildlife Foundation (2021, May). BCWF Investigation Reveals Flawed Process for Steelhead. Retrieved from https://bcwf.bc.ca/bcwf-investigation-reveals-flawed -process-for-steelhead/.

- ↑ BC Wildlife Foundation (2021, May). BCWF Investigation Reveals Flawed Process for Steelhead. Retrieved from https://bcwf.bc.ca/bcwf-investigation-reveals-flawed -process-for-steelhead/.

- ↑ BC Wildlife Foundation (2021, May). BCWF Investigation Reveals Flawed Process for Steelhead. Retrieved from https://bcwf.bc.ca/bcwf-investigation-reveals-flawed -process-for-steelhead/.

- ↑ BC Wildlife Foundation (2021, May). BCWF Investigation Reveals Flawed Process for ↵↵Steelhead. Retrieved from https://bcwf.bc.ca/bcwf-investigation-reveals-flawed↵↵-process-for-steelhead/

- ↑ BCWF. (2019, September 30). BCWF FOI reveals a flawed decision-making process for Endangered Steelhead. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from https://bcwf.bc.ca/bcwf-foi-reveals-flawed-decision-making-process-for-endangered-steelhead/.

- ↑ BCWF. (2019, September 30). BCWF FOI reveals a flawed decision-making process for Endangered Steelhead. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from https://bcwf.bc.ca/bcwf-foi-reveals-flawed-decision-making-process-for-endangered-steelhead/.

- ↑ BCWF. (2019, September 30). BCWF FOI reveals a flawed decision-making process for Endangered Steelhead. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from https://bcwf.bc.ca/bcwf-foi-reveals-flawed-decision-making-process-for-endangered-steelhead/.

- ↑ BCWF. (2019, September 30). BCWF FOI reveals a flawed decision-making process for ↵↵Endangered Steelhead. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from https://bcwf.bc.ca/bcwf-foi-reveals-flawed-decision-making-process-for-endangered-steelhead/.

- ↑ BCWF. (2019, September 30). BCWF FOI reveals a flawed decision-making process for Endangered Steelhead. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from https://bcwf.bc.ca/bcwf-foi-reveals-flawed-decision-making-process-for-endangered-steelhead/.

- ↑ BCWF. (2019, September 30). BCWF FOI reveals a flawed decision-making process for Endangered Steelhead. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from https://bcwf.bc.ca/bcwf-foi-reveals-flawed-decision-making-process-for-endangered-steelhead/.

- ↑ BCWF. (2019, September 30). BCWF FOI reveals a flawed decision-making process for Endangered Steelhead. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from https://bcwf.bc.ca/bcwf-foi-reveals-flawed-decision-making-process-for-endangered-steelhead/.

- ↑ Government of Canada. (2018, August 23). Technical Summaries and Supporting Information for Emergency Assessments - Steelhead Trout. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/species-risk-public-registry/cosewic-assessments-status-reports/steelhead-trout-2018.html

- ↑ NCRCD. (2014, October 26). Steelhead Trout. Retrieved from https://naparcd.org/steelhead-trout/#:~:text=Importance,and require cool, clean water.

- ↑ BC Ministry of Fisheries. "BC Fish Facts". BC Gov.

- ↑ Johnson Gottesfeld, Leslie (December 1994). "Conservation, Territory, and Traditional Beliefs: An Analysis of Gitksan and Wet'suwet'en Subsistence, Northwest British Columbia, Canada". Human Ecology. 22: 443–465 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Effects of Fish Extinction on Ecosystems (PDF) Science for Environment Policy: 12. July 2007 - via European Commission.

| This conservation resource was created by Course:CONS200. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |