Course:CONS200/2019/Impacts of Recreation on Conservation Efforts for Grizzly Bear Populations in BC

Introduction:

British Columbia is home to one quarter of the population of Grizzly bears in North America.[1] They not only play an important role in maintaining balance in the ecosystem, but are also vital socially and culturally to residents in British Columbia. However, it shows that the grizzly population is in a rapid decline due to activities related to recreation, including hunting and urbanization in the form of roads, rails, and constructions.[2] Conservation actions for the grizzly bears have been implemented by related departments in BC with reinforced hunting bans and improvements in protection areas in national parks.[3]

Grizzly Bears (Ursus arctos)

Characteristics

The grizzly bear is the second largest land carnivore in North America[4]. It is a solitary animal, which means that individual bears like to have a private range of residence. But these often overlap and they does not violently defend. They only have humans as predators. It should be noted that grizzly bears are not hibernators. They can stay active and strong during winter, even though their body temperature decreases a few degrees and the respiration speed becomes slower.

Habitats

in British Columbia, bears live in a variety of habitats including old-growth forests, coastal sedge meadows and south facing avalanche slopes.[5] In the early summer months, most bears use alpine and subalpine meadows.[5] In midsummer through early fall, they move to coastal habitats and concentrate along streams. [5]They don't have specific preference in lattitude.[6] According to their recorded habitats, brown bears generally seems to prefer semi-open country[6], with rich distribution of vegetation that can allow them rest in the daytime. They previously living in plain areas, but now their habitats can range from dense forestland to alpine meadow or arctic tundra[4]. Not all bears follow this typical pattern of change in habitats, as some do not migrate to streams and instead remain in high-elevation habitats throughout the year.[5]

They are actually omnivorous, eats both meat and vegetation[4]. Plants make up 80 to 90 percent of the grizzly's diet. They concentrate along streams to feed on spawning salmon around early autumn[5]. In the late fall, grizzly bears migrate to bear-producing habitats as a source of food. [5]Additionally, they will also take advantage of food remains and garbage left by people[4].

Reproduction

Breeding of the grizzly bear occurs in the late spring. [5]On average, females reach sexual maturity between four to seven years of age. [5]They have a gestational period of six to eight weeks before giving birth. [5]Every female bear approximately gives birth to one to three cubs around every three years. [5]The offspring then remain with the mother for two to four years before weaning.[5]

Location

Distribution and Fragmentation

Globally, grizzly bears (brown bears) can be found in Canada, the United States, Russia,China and at least 40 other Eurasian countries[3]. Despite the trend of extinction, the Russia and 22 European countries still harbour some 50,000 brown bears, which is divided into 10 different populations. The United States, whichis very similar to Canada in terms of geography, ecology and culture, grizzly bears only remain in the about 48 states today[3].

In Canada, the grizzly bear population is scattered over approximately 1,000,000 km2 of western Canada, including the furthest west province of British Columbia.[7] There are about 15,000 Grizzly bears in B.C., which is about a quarter of its North American population. Of the 56 extant Grizzly bear population units in B.C., 9 are classified as threatened species,which is due to the serious fragmentation of bear groups.

In the northern areas of British Columbia and extending to the Yukon, there was evidence of natural fragmentation of the population from the glaciated mountains, which is in contrast to the spatial pattern of fragmentation in the more southern parts of their distribution.There was also extensive fragmentation of grizzly bear population that correlated to settled mountain valleys and major highways. In disturbed areas of British Columbia, most inter-area movements that were detected were made mostly by male bears, with few female bears identified. North-south movements of populations within mountain ranges and across ВС Highway 3 were more common than east-west movements across settled mountain valleys.

Current Status and Major Conflicts

The current status of Grizzly bears are becoming increasingly serious. They considered "Vulnerable" by the B.C.Conservation Data Centre in 2012, and are classified as a species of Special Concern by the federal Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC)[1]. To be more specific, Grizzly bears are extinct several areas in British Columbia:

- The Peace Lowlands around Ft. St. John and Dawson Creek[1];

- The dry southern interior areas from the US border to north of Quesnel[1];

- The lower Fraser Valley and the Sunshine Coast[1].

The major cause of this is the conflicts between development of human society and Grizzly bears survival and reproduction:

- Conflicts between original habitats of bears and land use of humans. For example, human settlements, agriculture use. These often results in bears being killed or manual relocated to other places.

- Bears' populations are being further alienated or fragmented by human activities, for example, by high density road networks with high traffic volumes.

Importance

Natural Importance

- Grizzly bears are a symbolic species of ecological integrity, which represents much of what residents and visitors appreciate about B.C.’s natural beauty[1];

- Grizzly bears play the vital role of the systems where large predators and their prey play out their millennia-old roles[1]. These systems are extincting in the entire North American continent.

- They are considered as “umbrella”[8] species for the sustainability of those landscapes that support bear populations. The fragmentation of grizzly bear's population caused by the recreation infrasture dispersal leads to the reduction other species' viability. Because those landcpes will also support many other species in the local ecosystem. The absence of its roles will ultimately decrease global biodiversity.

- A healthy and balance ecosytem in BC is maintained by grizzly bears population [9]. For example, they indirectly allocate nutrients from salmon remains into forests ecosystems, and transports seeds through feces.

Cultural and Social Importance

- Grizzly bear hunting and exhibition activities are significant economic income and social components of B.C.’s tourism and recreation industries.[1] By the interactions between humans and grizzly bears, the distance between culture and nature is narrowed, which contributes to people's admiration and respect to environment.

- The unstable situation of grizzly bears will raise the tendency of its harming activity towards human, which will threaten the safety of the neighborhood close to their habitat region and cause finacial loss of individuals and community.[10]

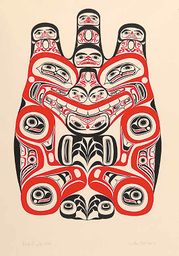

- The grizzly bear is considered a popular, revered animal especially in western and aboriginal cultures. Specificly, they are an important part of the culture of First Nations People living in British Columbia[11]. The decreasing population will cause people's sorrow and panic in some cultures.

Conservation Efforts

Laws/ Policies

The Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection (MWLAP) controls grizzly bear management policy in B.C. under the British Columbia Grizzly Bear Conservation Strategy (B.C. Government 1995b).[12]

The Conservation Strategy identifies four management goals:

1.To maintain in perpetuity the diversity and abundance of grizzly bears and the ecosystems on which they depend throughout British Columbia.[12]

2. To improve the management of grizzly bears and their interactions with humans.[12]

3. To increase public knowledge and involvement in grizzly bear management.[12]

4.To increase international cooperation in management and research of grizzly bears.[12]

The British Columbia Grizzly Bear Conservation Strategy has established large and secure ecosystems for the management of Grizzly Bears to ensure for long-term survival, to protect their population and the habitat that they live in, free from harvesting. [12]As of 2003, numerous grizzly bear management areas have been identified but are not protected and 6% of the province is protected by provincial parks that are permanently closed to grizzly bear harvest. [12] The Strategy calls for increased enforcement and penalties to handle violations of the British Columbia Wildlife Act, to advise the provincial government on the conservation of grizzly bears, to increase research on grizzly bear ecosystems, to change all hunting to Limited Entry Hunting (LEH), and to establish a Habitat Conservation Fund to help fun for grizzly bear research. [12]The Strategy requires a comprehensive environmental education program to increase public awareness between human and bear interactions.[12]To increase international cooperation, the Strategy calls for cooperation of all jurisdictions in which grizzly bears reside.[12]

Regulations

The Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection (MWLAP) administers the British Columbia Wildlife Act in seven regions and in Victoria through the use of wildlife and biodiveristy programs.[12]

The Wildlife Harvest Strategy (B.C. Government 1996) and the Grizzly Bear Harvest Procedure (B.C. Government 1999) in addition to the Conservation Strategy, manage the grizzly bear harvest. [12]

Population Management

Limited Entry Hunting (LEH)

Limited Entry Hunting (LEH) along with area closures and agency control of problem bears aids in population management of grizzly bears. [12]For each LEH zone, and allowable harvest is approximated and set and hunting authorizations are issued as guide-outfitter quotes and to the First Nations.[12] The amount of authorizations for each location available is determined by the Director of the Fish and Wildlife Recreation and Allocation Branch. Mandatory inspections of all legally harvested bears helps determine the annual harvest.[12]

Guide-outfitter quotas and allocations to the First Nations are determined by regional managers of environmental stewardship.[12] A licensed guide-outfitter must be present if a non-resident chooses to hunt grizzly bears. [12]As of 2003, the annual bag limit for grizzly bears is limited to one.[12] Guide-outfitter reports and a LEH questionnaire help track hunter success and efforts.[12]

Grizzly bear hunting is prohibited in all national and some provincial parks. In the southern interior of British Columbia, grizzly bear hunting is restricted to the spring seasons meanwhile in the northern and coastal regions of British Columbia, hunting can occur during both spring and autumn seasons. [12]However, hunting is off limits indefinitely in 24%, and temporarily in 13% of the species’ historic range as of 2003.[12]

Education

To raise awareness of grizzly bear conservation among the junior and senior high school students, the BC grizzly bear conservation decision has designed an integrated education program.The project includes efforts on grizzly bear safety, waste management, and knowledge of grizzly bear habitat and wildlife management policies.Education programs, field projects and environmental teams are key elements of the strategy.

The education program, Grizz Ed, was established in 1997 through two existing programs ( Project Wild and The Green Team) and included a touring education team in grades 4-7.The grizzly bear biology program, which began in 1998, is one of the wildlife programs. [3]

Bear Smart, a community based program, was developed in June 2002 with the intention to reduce the bear and human conflict. This program certifies communities as Bear Smart when they have met specific standards and regulations and was designed for municipalities and communities in grizzly bear environments. [12]

In response to the deaths of grizzly bears caused by foraging for food near human settlements, managers of the office of grizzly bear conservation have reduced the death rate by teaching grizzly bears to avoid human locations naturally. Local residents can call the office of grizzly bear conservation hotline for help.[3]

The evidence for the problem

Impacts of recreation:

1. Hunting impact:

British Columbia has a long history of grizzly bear hunting. Residents hunted grizzly bears long before Europeans settled.In the mid-20th century, when the grizzly bear was officially considered a hunting animal, there were management programs to ensure sustainable hunting, and in the spring of 2001, there was a brief ban on hunting grizzly bears.[13] The rate of hunting deaths was rising from 50 to 320 across BC province from 2001 to 2011. The mortality rate of the female is higher than that of the male.[14]Since 1976, an average of 297 grizzly bears have been legally killed by hunters each year.[15]In 2010,Grizzly bear hunting was allowed in about 65 % of BC province.[13]Increased awareness of grizzly bear conservation and improved hunting laws in recent decades have led to an increase in grizzly bear population.[7] For example,since 2008,laws governing grizzly bear hunting have set limits on maximum female catch because female mortality is directly related to grizzly population.The department of the environment stipulated that grizzly bear mortality in high-quality habitats cannot exceed 6 percent.[13]

2. Conflict impact:

The conflict between grizzlies and humans occurs mainly in the spring and summer.[16]A lack of food supplies is a major cause of conflict between humans and grizzly bears. In some areas of BC province, human-grizzly conflict peaks when salmon spawning is low. For every 50 percent reduction in salmon populations, conflict with humans increases by 20 percent. A solution to the problem of spawning salmon for bears has been studied in a fisheries plan. [17]Since 1976, 31 bears have been killed by animal control officers for conflicts between animals or humans and bears.[15]Between 1979 and 2006, at least 83 grizzlies were removed from Rocky South BC due to management conflicts between humans and bears.[7] In 2017,Chris Doyle who is the deputy director of the department of conservation services in British Columbia said grizzlies were involved in 430 complaints of human-wildlife conflict.Twenty-seven grizzly bears were killed because of the conflict. [16]

3. Road and railway impact:

Roads cause loss of functional habitat and change motion paths, and become a threat to the wildlife. For grizzly bear, roads with different traffic capacities can affect the location and size of their habitats and their behavior patterns.[18]Many grizzly bears died from traffic accidents and habitat loss. When road density is less than 0.6 km per square kilometer, roads have no negative impact on the use of grizzly bear habitat.When the road density is above 1 km per square kilometer, the negative effect will be significantly enhanced. [1]Since 1976, on average, 8 bears have been killed illegally, and 4 are known to have been killed on roads and railways, but some deaths by illegal highways and railways are undetected. [15]Large numbers of grizzly bears have been killed on roads, rail tracks, and in clashes with humans in the elk valley in southeastern British Columbia. 68% of grizzly bear deaths in the valley come from non-hunting causes. 54% of these non-hunting deaths are caused by collisions with vehicles and trains, and 33 % by human-bear conflict, which are shot in ranches and urban areas . Poaching accounts for 13% of bear deaths.[19]

4. Human settlements impact:

Grizzly bear communities are isolated by human settlements, agriculture, and utility corridors at the bottom of major valleys.[15]From the mid-19th century to the 1970s, human settlements were dispersing grizzly populations, and larger settlements were associated with higher genetic distances, indicating that the expansion of human communities led to the fragmentation of grizzly communities. The settlement has reduced the activity of both male and female bears.While each gender appears to be affected by the same stress, they have different thresholds.In unstable regions, there is no difference between male and female mobility rates, suggesting that although female moved over shorter distances, they moved over geographic areas with minimal disruption.[7]In BC province, human settlement and development pose a severe threat to grizzly bears. In 2017, the auditor-general of BC province, Carol Bellringer said in a report critical of the government's management that the most significant risk to British Columbia's 15,000 grizzly bears is habitat degradation caused by increased infrastructure, expansion of gas and oil development and human settlement.[20]

Related stakeholder

First nation: They can harvest grizzly bears for food, social or ceremonial purposes because they have the indigenous right or treaty rights.[21]They also propose to protect grizzly bear habitats, such as the Haida Nation in BC province who claimed their land to protect grizzly bears.[22]

Resident and non-resident hunters: In August 2017, the BC provincial government decided to ban their hunting of grizzly bears, including grizzly bears in the Great Bear Rain forest. In addition to the purpose of protecting grizzly bears, the purpose of promoting grizzly bear viewing economy is to preserve a certain number of grizzly bears and provide opportunities for local people and foreign tourists to see grizzly bears in their habitats.[21]

Conservationist: Their solution emphasizes protecting grizzlies. These conservation groups support limiting human use around grizzly bear habitats and designing human development programs based on ecological constraints. They also propose reducing the number of bear projects for recreational purposes and creating areas that can meet the needs of grizzly bears. They oppose the idea that management should prioritize human use, and support prioritizing grizzly bear conditions and ecological integrity. They think it is necessary to improve cooperation between management agencies and other groups to achieve bear protection. They also strongly oppose research techniques that change the behavior of bears, such as radio collars.[23]

Landscape manager:In terms of habitat protection, they believe that human development should be reduced near bear habitats and the area of bear habitats in the wild should be increased, but they do not support further restrictions on human land use. They say the entertainment programs in conservation areas of grizzly bears should be moved to other areas.[23]

Options for remedial action(s)

Human activities have dramatic effects on the distribution and abundance of wildlife. Increased road densities and human presence in wilderness areas have elevated human-caused mortality of grizzly bears and reduced bears’ use.

- Road density is a useful substitute for the negative effects of human land use on grizzly bear populations, but spatial configuration of roads must still be considered. Reducing roads will increase grizzly bear density, but restricting vehicle access can also achieve this goal. It is demonstrated that a policy target of reducing human access by managing road density below 0.6 km/km2, while ensuring areas of high habitat quality have no roads, is a reasonable compromise between the need for road access and population recovery goals. Targeting closures to areas of highest habitat quality would benefit grizzly bear population recovery the most.[24]

Similar to vehicles on roadways, trains frequently kill wildlife via collisions along railways. Results support local management knowledge that some bears in the region use the railway to forage and supplement their diets with spilled grain.

- It is suggested that managers continue to reduce the risk of bears being killed by trains by reactively removing grain and ungulate carcasses from the railway, reducing the amount of grain spilled by trains, and target mitigation to the specific individuals and locations that attract recurrent rail-based foraging.[25]

Traffic patterns caused a clear behavioural shift in grizzly bears, with increased use of areas near roads and movement across roads during the night when traffic was low. In addition, bears selected private agricultural land, which had lower traffic levels, but higher road density, over multi-use public land.

- Future management plans should employ a multi-pronged approach aimed at limiting both road density and traffic in core habitats. Access management will be critical in such plans and is an important tool for conserving threatened wildlife populations.[26]

Fragmentation in the interior mountains is affecting grizzly bears. Management strategies at local and regional scales designed to reconnect fragmented units may reduce the possibility of further range contraction in the region.

- It is recommended to secure habitat for bears to safely disperse between adjacent areas, and enhance inter-area movements. Maintenance or enhancement of habitat to ensure female dispersal. Linkage areas need to be identified and established wide enough to allow females to live and reproduce within them during their slow dispersal. Managers also need to maintain areas with low human densities to reduce human-bear conflicts and thus bear mortalities during movements through fracture zones. [7]

Conclusion

Illustrated through the research, human recreation and urbanization activities have significantly impacted grizzly bear population. Examples would be increase in road density which results in habitat loss and shifts in grizzly movement/behavioural patterns, railways that results in collision deaths of grizzly bears, and conflict impacts due to human settlement near grizzly habitats. Crucial recommendations is for authorities to manage and reduce road density near grizzly habitat, and to secure and acknowledge habitats in order to avoid conflict

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 "Grizzly Bear Population Status in B.C." Ministry of Environment BC. November 2012.

- ↑ Fortin, Jennifer K. "Impacts of Human Recreation on Brown Bears (Ursus arctos): A Review and New Management Tool". PLoS One. 11.1.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Gailus, Jeff (April 2010). "Ensuring a future for Canada's grizzly bears A report on the sustainability of the trophy hunt in B.C." (PDF). Natural Resources Defense Council. line feed character in

|title=at position 45 (help) Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name ":10" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Animal Facts: Grizzly bear". Canadian Geographic. June 15, 2006.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 Schwartz, C., Miller, S., and Haroldson, M. (2003). "Grizzly bear". Wild Mammals of North America: Biology, Management and Conservation. Second edition: 556–586.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hunter., Luke (2011). Carnivores of the World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691152288.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Proctor, M. F., Paetkau, D., Mclellan, B. N., Stenhouse, G. B., Kendall, K. C., Mace, R. D., ... & Wakkinen, W. L. "Population Fragmentation and Inter-Ecosystem Movements of Grizzly Bears in Western Canada and the Northern United States" (PDF). Wildlife Monographs. 180: 1–46 – via JSTOR. line feed character in

|title=at position 83 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Grizzly Bear Population Status in B.C. State of Environment Reporting". Ministry of Environment, BC. November 2012.

- ↑ PROCTOR, MICHAEL (2012). "Population Fragmentation and Inter-Ecosystem Movements of Grizzly Bears in Western Canada and the Northern United States". Wildlife Monographs. 180: 1–46.

- ↑ Can, Özgün Emre (2014). "Resolving Human‐Bear Conflict: A Global Survey of Countries, Experts, and Key Factors". Conservation Letters. 7: 501–514.

- ↑ Clark, Douglas, A. (2009). "Respect for Grizzly Bears: an Aboriginal Approach for Co-existence and Resilience". Ecology and Society. 42. line feed character in

|title=at position 71 (help) - ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 12.14 12.15 12.16 12.17 12.18 12.19 12.20 12.21 Peek, J., Beecham, J., Garshelis, D., Messier, F. Miller, S., and Strikeland, D. (March 6, 2003). "Management of Grizzly Bears in British Columbia: A Review by An Independent Scientific Panel" (PDF): 1–90. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 BC minstry of environment (7 October 2010). "Grizzly Bear Hunting: Frequently Asked Questions" (PDF).

- ↑ Artelle, K. A., Anderson, S. C., Cooper, A. B., Paquet, P. C., Reynolds, J. D., & Darimont, C. T. (2013). "Confronting uncertainty in wildlife management: Performance of grizzly bear management". PLoS One. 8.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 environmental reporting BC. "Grizzly Bear Population Status in B.C."

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Gemma Karstens-Smith (Oct 07, 2017). "A very large-scale problem': B.C. sees more than 20,000 human-wildlife conflicts in 2017". The Canadian Press. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ RANDY SHORE (2016). "Killing grizzly bears to reduce human-bear conflict is ineffective and may even have the opposite effect, according to a new study by B.C. scientists". vancouver sun.

- ↑ Northrup, J., Pitt, J., Muhly, T., Stenhouse, G., Musiani, M., & Boyce, M. (2012). "Vehicle traffic shapes grizzly bear behaviour on a multiple-use landscape". Journal of Applied Ecology. 49: 1159–1167.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ Hamilton, A. N., Heard, D. C., & Austin, M. (2004). "Human activities causing increase in B.C. grizzly bear deaths: study".CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ Kendra Mangione (October 24, 2017). "Habitat, not hunting, the greatest threat to B.C. grizzlies: report". news vancouver.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Victoria (December 18, 2017). "B.C. government ends grizzly bear hunt". BC government news.

- ↑ THE OUTPOST (DECEMBER 31, 2013). "Bear Witness: First Nations Protect Grizzlies in British Columbia". WILDLIFE. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 23.0 23.1 CHAMBERLAIN, E. C., RUTHERFORD, M. B., & GIBEAU, M. L. (2012). [10.1111/j.1523-1739.2012.01856.x "Human perspectives and conservation of grizzly bears in banff national park, canada"] Check

|url=value (help). Conservation Biology. 26: 420–431.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Lamb, C. T., Mowat, G., Reid, A., Smit, L., Proctor, M., McLellan, B. N., Marnewick, K. (2018). "Effects of habitat quality and access management on the density of a recovering grizzly bear population". Journal of Applied Ecology.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ Murray, M. H., Fassina, S., Hopkins,John B., I.,II, Whittington, J., & St Clair, C.,C. (2017). "Seasonal and individual variation in the use of rail-associated food attractants by grizzly bears (Ursus arctos) in a national park". PLoS One.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ Northrup, J., Pitt, J., Muhly, T., Stenhouse, G., Musiani, M., & Boyce, M. (2012). "Vehicle traffic shapes grizzly bear behaviour on a multiple-use landscape". Journal of Applied Ecology.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

| This conservation resource was created by Will. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |