Course:ARST573/Faith Based Archives

Faith-based archives contain the records of religious groups, communities and organizations. Religious record-keeping has a long and diverse history with some archives tracing their history back hundreds of years.[1] It is hard to generalize faith-based archives given that they exist in many forms and in many different contexts. This wiki focuses on modern faith-based archives in North America and the UK. Faith-based archives can range in size and scope. Some religious institutions have highly centralized archival networks such as Anglican diocesan archives or Baptist convention archives. Faith-based archives may be regional as well, such as the Jewish Historical Society of Edmonton and Northern Alberta or the Hindu Archive Project of Britain. Communities may also keep a small in-house archives like those of the East London Mosque.[2] Archives may transfer records to another institution if they do not have their own archival program.[3] The archival program of a religious institution can depend on the specific mandate. Some faith-based archives are aimed at providing better access for historical and cultural research. Others may focus on preserving and maintaining the records of the community for their own use.[4]

History

Modern faith-based archives come from a long history of religious record keeping. Traditions vary between countries, communities and individual places of worship but religious record keeping is an ancient practice, dating to the 4th century BCE in places such as Britain.[5] In the middle ages, places such as Christian churches and monasteries became storehouses for administrative records, illuminated manuscripts and relics.[6] Other religious archives such as Jewish archives existed in the early modern period but these records were usually for use by their own community. It was not until the later 20th century that many fully formed archival programs began to develop throughout North America and Europe. In North America and Britain faith-based archives are predominantly Christian and Jewish.[7] Much of the focus of the archival community has been on these Christian and Jewish Archives, in terms of studying them and providing resources.[8] However faith-based archives from other communities have existed along side the more mainstream faith-based archives.[9] In the past 30 years, there has been an effort to interact with these archives by groups such as The National Archives of the UK's Religious Archives Group.[10] The goal of such outreach is both to inventory what records exist but also to make communities aware of the resources available to them through professional archival associations.[11] Today, many faith-based archives work to better preserve their own records and improve access for their own community and the wider public.

Types of Material

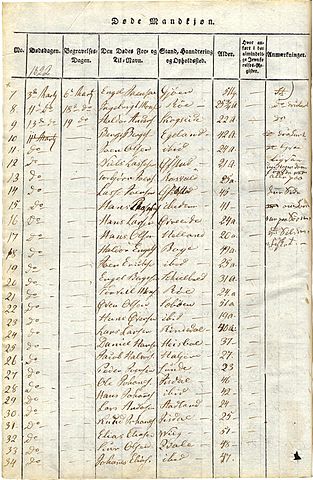

Faith-based archives can have a range of material in their holdings. Typical archival material such as textual records can include administrative records, birth, marriage, and death records, personal records of the clergy or community, and associated religious groups. Archival material may also come from various religious communities depending on the archives. The Southern Baptist Historical Archives has collection material from Baptist communities all over the United States and the world.[12] Faith-based archives also hold photographic material and audio/visual material related to the community or specific institution. Unique holdings of faith-based archives can include non-typical archival material such as religious artifacts or community memorabilia. Communities may have different criteria and standards for caring and interacting with such objects as they can have great significance to the community or religious institution. The Shambhala Archives, for instance, has the clothing and relics from the Tibetan Buddhist teacher Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche as part of their collection.[13]

Uses

Historical Research

Religious records are often used for historical research. Religious records can provide an invaluable look into religious communities activities, social context and their role within society at large.[14] However, there can be contention over access to these records depending on the religious group.[15] Religious communities may seek to open their own archives to promote their records for use in historical texts. The Jewish Theological Seminary of America undertook a large effort to collect, arrange, and make available the records of the Conservative Jewish movement in America. Their stated purpose was to promote historical discourse on Conservative Judaism. Another example is the Hindu Archive Project at the Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies (OCHS). The OCHS wanted to create a sense of history among the diverse Hindu community in Britain.[16] The Hindu Archive Project was part of a larger effort to preserve modern Hindu culture. Another project by the OCHS was to collect oral histories, "focusing on the first generation of British Hindus mainly arriving from East Africa in the 1970's."[17] Yet, many faith-based archives do not allow their holdings to be used for historical research. Some groups keep records largely for administrative purposes and do not provide access for researchers. Others cite a distrust of outsiders seeking to represent their faith and may only provide access to approved researchers.[18]

Cultural Memory

Faith-based archives are also used to create and preserve a sense of collective history for the religious communities that they serve. Going further, the Religious Archives Group 2010 Survey argues, "[Religious records] constitute a crucial element of our national heritage. Not all such collections are equally accessible but it is important that they are preserved, in all their diversity, by their owners or creators, as part of this patrimony."[19] The ability to provide a sense of history and cultural context is one of the reasons often cited by faith-based archives such as the East London Mosque Archives and the Hindu Archive Project as to why their programs exist. On the subject of cultural memory, Tim Macquiban, an archivist at the Methodist archives at Welsey College argued that the sense of history within the Methodist archives made his faith stronger.[20] However not all religious communities keep records, D’arcy Hande and Erich Schultz explore this, using the evangelical Lutheran Church in British Columbia as a case study.[21] Compared to other Protestant denominations in British Colombia, the Lutheran Church struggled to establish a foothold. The authors think, in part, it was because of a lack of established local identity. Without a strong collective memory, the Lutheran Church failed to stand apart in British Columbia and could not attract followers.[22] Hande and Schultz’s case study is limited in scope and does not represent the experience of every religious community. It however provides one example of the role archives, or lack thereof, play in creating cultural memory among religious communities.

Evangelicalism

Related to the cultural memory aspect of faith-based archives is the use of religious records in evangelical efforts. While not all faith-based archives are used in this way, some religious groups may use records of past activities or material produced by the community to showcase their cause and mission.[23] There is often a correlation between religious communities with larger archival programs and the use of records in evangelicalism.[24] A notable example is the Catholic Church, where the Papal committee on archives lists evangelical uses of records as one of the major reasons the Church has supported and maintained archives for so long.[25] This type of outreach can take several forms. Archives can use archival material in their own publications, promote the use of archival material among community members or offer access to records for researchers to use in publications.

Genealogy

Faith-based archives are often used in genealogical research. Religious institutions often keep detailed information about their communities. Examples include baptismal, marriage and death records, registers, financial records and local maps of towns or grave sites.[26] In some cases, especially for the 18th-19th centuries, religious records may be the only record of activity in a region.[27] This is not just limited to official institutional records. The donated papers and other material given to faith-based archives often contain valuable information about early community members. Jewish Archives in the UK are working with historical societies to digitize their records partly because of the interests of genealogists.[28] It is also becoming common for faith-based archives to provide access to their records in partnership with other genealogical research websites such as Ancestry.com[29] Some faith-based archives use their genealogical records as a form of outreach, prioritizing the digitization of these records and encouraging their use. The effort to digitize and make available religious records related to genealogy is an on-going effort. As the Religious Archives Group 2010 Survey noted “Genealogical research is impossible without recourse to religious records particularly before the introduction of civil registration in the 19th century.”[30] While the survey covered only Britain, it illustrates the important information held within faith-based archives for both religious communities and the wider public.

Administrative and Legal

Faith-based archives also maintain archives for their own administrative use. The amount and type of material kept depends on the parent body. For example, a Catholic archdiocese may provide both archival and records management services to its users. Established retention and disposition schedules are more common at this level as well.[31] Established institutions also keep good records for legal protection as well.[32] Faith communities that do not keep archives may retain records for legal or administrative reasons.[33] In these situations, archival transfer to a repository may or may not happen depending on the priorities and desires of the community.[34] There is discussion among religious archivists on whether to leave records with their creators or transfer them to a repository given their importance in research and legal matters.[35] Most of the time, it is the religious group themselves that must show interest in transfer in order for the records to be moved.

Practical Challenges

Lack of Resources

Faith-based archives often lack archival professionals. Many of those who work in faith-based archives are from the affiliated religious community. From the few surveys conducted about religious archives, about 75% of those working in them are volunteers or staff without archival training.[36] Often, religious officials serve as archivists in their respective institutions. Margaret Williams, the Honorary Secretary, of the Catholic Archives Society wrote, "Most diocesan archivists are priests. They have to combine this role with other duties, usually the care of a parish and the time they can allow for the archives varies. Some work as archivists several days each week, others rely greatly on the help of lay people, who may be employees or volunteers."[37] Since many faith-based archives lack resources to begin with, the lack of sufficiently trained staff can result in the loss of records or damage to existing holdings.[38] Furthermore, the priorities and history of the religious group often determine what resources are allotted to an archival program.[39] Successful faith-based archival programs are those that are made a priority within their parent organization and are seen as serving an important role in the community.[40]

Faith-based archives have addressed these challenges in a number of ways. On an national level, archival associations may provide resources such as grants, training or guidance.[41] Special interest groups within archival associations may also act as a centralized resource where religious archivists can interact and discuss issues with each other.[42] Faith-based archives that are not within a larger network also partner with other archives to share resources and make their material available online.[43]

Custody of Records

Faith-based archives may face challenges related to questions of custody and record deposit. For the most part, religious records are permanently retained by their parent organization.[44] Centralized and hierarchical institutions usually have their own archives and clear procedures on what records to deposit and transfer. The organizational structure of these institutions also makes records management easier. Individual communities also create and maintain their own archives as was done with the records of the East London Mosque.[45] Few of these archives are housed in purpose built repositories but most, around 90%, have some space for archival records.[46] For faith-based archives that lack such resources questions remain about how to keep records or if to transfer custody to an archival institution. Some communities are members of larger organizations like the many independent churches that make up the Southern Baptist Convention. [47] These communities can send their records to a central repository although archival transfer in such cases is not always mandated. Another option is to transfer the records to a third-party repository such as a public or university archives. Transfer to an established archives allows for the professional preservation of the records. It may also provide better access and relieve pressure on the religious community if they are running out of space for their records.[48]

Contemporary Issues

Non-traditional Communities

One issue discussed by some religious archivists is if the archival community should seek to document faith communities that are outside of the mainstream. James Lambert discusses this from a historical perspective in an article on faith-based archives in Canada. Lambert argues that both the importance of faith in people's lives and its impact on society should motivate archivists to seek out more faith communities, citing Wiccans as an example of an underrepresented community.[49] In contrast, it has been argued that because many religious communities are small and their records are used for mostly administrative purposes, any attempts to solicit records from these groups may harm the records more than just leaving them in place.[50] Communities may also not want to deposit records if they contain important or sensitive information. Among archivists, there does not seem to be a consensus as to how or even if archives should collect the records of these communities.

Another topic of discussion is what constitutes a faith-based archives. While the majority of faith-based archives are sponsored by a religious community or institution, there are faith communities that run parallel to these institutions such as faith-based LGTBQ groups. Examples include Dignity and New Wave Ministry, both Catholic groups that serve gays and lesbians who have been ostracized from the mainstream Catholic Church.[51] Churches that have better relations with the LGTBQ community such as the United Methodist Church also have chapters that specifically serve the LGTBQ community. Archivist Harold Averill argues these groups represent an important part of the modern expression of faith but that too often these records are kept separate from any faith-based archives.[52] Most of the records from these kinds of groups are housed in LGTBQ archives if they are in archives at all.[53] While Averill believes LGTBQ archives play an important role in the community, he argues faith-based archives are not just those of established institutions. Faith-based archives should include records of related non-traditional communities.[54] There is no clear solution to what Averill proposes but it is important for archivists to consider what appraisal methods are used in their collections and how might to better include more records from varied groups within their archives, if able.

One trend is for communities to share resources and create their own archives. Often these regional religious archives are members of regional or national archival associations. The Religious Archives Group 2010 Survey suggested that, at minimum, archival associations and larger institutions should make resources available for faith-based archives to use.[55] The Religious Archives Group itself provides an "Archives for Beginners" booklet online aimed to serve small faith-based archives without professional staff.[56] While not a possible solution for all communities it does show that many communities have a desire to retain their own records and make an effort to do so.

Social Justice and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Another issue confronting religious archivists is their role in social justice involving religious records. Social justice within archives is a heavily debated subject, presently there is no consensus among the archival community to to what extent archivists should practice social justice in their profession.[57] However, religious archivists face a unique challenge in this regard. Religious institutions play a significant role in society and their records attest to all of their activities, both good and bad. Reflecting on the nature of archives, power, and social justice, Randall Jimerson of Western Washington University writes, “Through most of human history, archives have served the needs and interests of the rich and powerful. What the call of justice asks archivists to accept is a responsibility to level the playing field. The archival profession as a whole—but not necessarily each individual archivist or repository—should assume a responsibility to document and serve all groups within society."[58]

One of the most prominent examples of how faith-based archives become involved both in controversy and social justice is the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) in 2008.[59] The TRC was the result of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, in which the church organizations responsible for running some of the Indian Residential Schools agreed to provide all records relating to them.[60] Additionally, one of the TRC’s responsibilities is to, “establish a research centre and ensure the preservation of its archives.”[61] Since the creation of the TRC, obtaining all relevant records has proved to be difficult.[62] There was no clear agreement of what constituted a relevant record. Even then, there was the problem of how to provide access to millions of records.[63] While many records have been transferred, many more were unusable due to poor condition or having been lost.[64] There has also been reluctance to hand over records. In 2014 the Canadian Federal Government refused to give the TRC full access to relevant records within its custody until ordered to do so by a judge.[65] Despite these challenges, the work of all those involved has been extremely important. Bruce Montgomery argues that archival evidence, “preserves the memory of the perpetrators and their crimes for the sake of historical accountability. It may hold the only memory of individual victims and how and why they vanished.”[66] For example, Melanie Delva, an Anglican archivist, used Church records to create a missing persons database to help First Nations families who did not know what had happened to their children.[67] The TRC provides an example of how religious archivists may be called to undertake social justice. While it is not the experience of every religious archivist, some may need to provide access to their records for such purposes if the need ever arises.

Canon Law and Privacy Concerns

Faith-based archives can have a variety of records within their holdings, some of which contain private or sensitive information. Rules governing access are often dictated by canon law depending on the religious institution. Like freedom of information legislation, canon law dictates when records are opened to the public and aims to protect personal information. For instance, the Church of England does not release the personal papers of any bishop until 30 years after their death, except with permission from the sitting bishop.[68] However canon law can be far more restrictive regarding sensitive internal records. An example is the Catholic Church and its laws about clerical secrecy. Clerical secrecy is supposed to protect all parties in the internal investigations of the Church but does not prevent church officials from withholding records from appropriate authorities in legal cases.[69] However as John Allen Jr., a reporter for the National Catholic Reporter writes, the Catholic Church has been accused of covering up reports of sexual abuse and in some cases withholding records.[70] Religious archivists must be aware of all legislation and theological laws governing access to their archives as there can be legal ramifications from not disclosing records at times.

Case Studies

Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto

History

The Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto (ARCAT) has existed in several forms since the Archdiocese of Toronto was created in 1841.[71] A diocesan archives falls under the authority of the Chancellor and before the 1970’s the records of the Archdiocese of Toronto were maintained by Chancery staff. Archival administration and access was limited. As more material was requested from the archives, ARCAT finally appointed Rev. Gordon Bean as the first archivist for the archdiocese in 1969.[72] An update to Catholic canon law in 1983 laid out the priorities for diocesan archives which included creating an inventory of all records within the archives. Since then, ARCAT has made significant strides in gaining intellectual control over their collection.[73] Today, ARCAT continues to maintain, preserve, and make available the records of the Archdiocese of Toronto and aims to have all aspects of their archival program up to Canadian archival standards.[74]

Unique Holdings

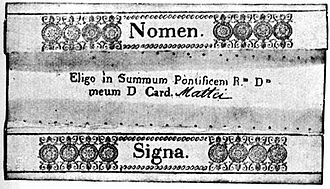

Like some other faith-based archives, ARCAT has unique holdings. Their special collections has a variety of materials including religious artwork, historical books, alter stones and relics.[75] They claim one of their most unique holdings is a blank ballot for voting in the Papal Conclave.[76] ARCAT also runs the Sacred Objects Exchange for parishes within the archdiocese. Through the program, ARCAT serves as a central repository for objects of spiritual significance. Parishes are encouraged to borrow and donate objects such as chalices, tabernacles, vestments, relics, statues and art that are used in Church services and programs.[77] ARCAT also restores items if they are physically deteriorating or if requested by the borrower.[78]

Services

ARCAT provides a number of services for Church institutions within the Archdiocese of Toronto such as parishes, church offices, and agencies.[79] As ARCAT is responsible for the records of the archdiocese, they provide records management to help ensure vital records are kept for legal and administrative reasons. To this end, ARCAT created the Sacramental Records Policy and Procedures Manual in 2011 with retention schedules and explanations on restrictions for certain records types.[80] An example of this is Ontario’s Adoption Disclosure Law passed in 2008. Parishes and ARCAT have records relating to adoptions but disclosing such information could only be done by the Provincial government. [81] Therefore, ARCAT could not legally release records. Certain records may also fall under similar privacy laws and ARCAT’s records management helps Church officials comply with all applicable legislation. Additionally certain Church records are needed for confirming certain rites.[82] Thus, it is vital parishes maintain such records for these religious and legal reasons.

ARCAT also provides a number of services for genealogists. ARCAT is unique in that diocesan archives often contain records with vital statistics such as baptismal, marriage, and death records.[83] ARCAT provides a list of what records pertain to genealogical research and how those records can be accessed and used.[84] ARCAT also provides a list of parishes, town names, and map locations to aid with genealogical research.

Hindu Archives Project

History and Mandate

The Hindu Archive Project is one of several projects overseen by the Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies (OCHS). The project aims to preserve the history and traditions of Hinduism in Britain.[85] The OCHS also hoped to create a sense of community among the diverse British Hindu population.[86] Therefore, the Hindu Archive Project was established to provide a place where members of different Hindu communities could deposit their records. Most of the records of the Hindu Archive Project can be requested for reference purposes, barring select cases.[87] The Hindu Archive Project collects a variety of material including textual records, photographs, audio/visual material, newspapers and memorabilia.[88]

Outreach

The Hindu Archive Project’s outreach is aimed mostly toward the British Hindu community.[89] It encourages the wider community to maintain and preserve records in several ways. The archive itself accepts any records related to Hindus or Hinduism.[90] The Hindu Archive Project promotes the donation of records as a way to preserve and create a sense of history among the community.[91] It also encourages donation to meet practical concerns such as a lack of space or resources to properly care for records.

Another way they encourage the preservation of records is by helping communities create their own archives. For communities who want to maintain their own records the Hindu Archive Project provides access to resources, technology and training to help run the archives.[92] It also helps to locate where records related to Hinduism in Britain are kept.

Challenges

The Hindu Archives Project faces several challenges. There are questions among the Hindu community and the project itself about how a central archive will affect individual Hindu communities. Some fear that a central archive could adversely affect local community history and remove records from their original context. There is also the need for a qualified archivist who is linguistically suitable for the position.[93] The material within the archive is not yet online, although this is a goal for the project. If they do publish the holdings online, care must be taken to consult the community on what material is appropriate for publication and to review any translations provided on the website.[94]

Jewish Archives and Historical Society Of Edmonton and Northern Alberta (JAHSENA)

History

The Jewish Archives and Historical Society of Edmonton and Northern Alberta (JAHSENA) was founded in 1996 by Uri Rosenzweig to house material collected for the centennial celebration of Edmonton’s Jewish community.[95] Since that time JAHSENA’s mission has been to preserve and protect the Jewish heritage of the region.[96] JAHSENA's collection is diverse; highlights of their collection include 150 meters of textual records, 15,000 photographs and 180 videotapes. They also collect non-archival items as part of their mandate such as memorabilia or artifacts that have significance to the community.[97] JAHSENA’s primary goal is to preserve such material for future generations and make their holdings available for outreach and educational programming. Their archival descriptions and some digital objects are available here

Partnerships and Funding

JAHSENA has fostered relationships within the Canadian archival community since its conception and doing so has become one of their stated goals.[98] In this regard, JAHSENA works with the Provincial Archives of Alberta and the Archives Society of Alberta to receive support with projects and developing RAD compliant descriptions. They also work with other Jewish societies on projects, their most recent is the Edmonton Jewish Cemetery website created in partnership with Edmonton Chevra Kadisha. The project cataloged obituaries, personal stories, photographs, and grave sites of those in the Edmonton Jewish Cemetery.[99] JAHSENA continues to work on community projects to make access easier and promote awareness of their holdings.[100]

JAHSENA provides an example of how independent faith-based archives generate the funds needed to operate and work on special interest projects. Through their partnerships with various archival associations they receive some funding and grants. They have been able to procure long-term sources of funding and hire a professional director.[101] As a non-profit organization, JAHSENA is also supported through various charitable donations. On their website, supporters of JAHSENA can buy different levels of membership ranging from $25-$100[102] It also puts on a variety of fundraisers, such as the biannual Casino Night.[103]

Outreach and Access

One of JAHSENA’s stated goals is to produce, “educational and publication projects encouraging interest in the history of these communities and their archives.”[104] To this end, JAHSENA publishes a tri-annual newsletter Yerusha (Heritage) which covers recent news as well as features articles based on their holdings. They host local exhibits in their institution, such as “The History of Jews in Western Canada”, and “TT100: Edmonton Talmud Torah @100."[105] Their special projects like the aforementioned Edmonton Jewish Cemetery also illustrate their work and value in the community.

While it is a private archives, JAHSENA makes their collection available to members of the community for reference purposes.[106] Material obtained by the archives will not be kept from researchers except in certain cases related to specific donor restrictions or physical deterioration of the original. Archival descriptions are available through an online catalog. JAHSENA has upload a limited number of photographs from their collections to the catalog. Examples of articles, photographs, and audio/visual material are also available on their website.

Shambhala Archives

History

Founded in 1987, the mandate of the Shambhala Archives is to ,"locate, acquire, arrange, describe, preserve, and make available all original records pertaining to the life and teaching of the founder of Shambhala, the Vidyadhara the Venerable Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, and of [his son] the Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche (Ösel Rangdrol Mukpo) and of [his] the Mukpo family.”[107] Located in Halifax, Nova Scotia the Shambhala Archives has grown to house one of the largest audio/visual collections of Tibetan Buddhism in the West. Chögyam Trungpa was the founder of several schools of Tibetan Buddhism.[108] In the 1970’s he asked that his teachings be recorded. Vajradhatu Recordings was established to record and make available all of his teachings for his students.[109] In the mid 1980's, Trungpa asked that his records be permanently preserved as well. Following his death in 1987, some volunteers worked to establish a permanent location for the large collection of audio/visual material and physical relics and make them widely available to followers.[110] The Shambhala archives also houses material from other Tibetan Buddhist teachers. A complete list of their holdings can be found here

Digitization Projects

One of the reasons the Shambhala Archives was founded was to make available the numerous audio and visual recordings of Trungpa and other Tibetan Buddhist teachers.[111] The Shambhala Archives have worked since its creation to restore and publish their material to a wider audience. This has been a challenge as much of their holdings date from the 1970’s and 1980’s.[112] As of 2015, the Shambhala Archives hopes to finish digitizing the 235 video tapes from the original Vidyadhara collection. Also, the Audio Recovery Project (ARP) was started in 1996 to reformat the over 10,000 audio holdings at the Shambhala Archives. The ARP was a major undertaking for the archives and has been mostly done in-house.[113] While not all the material is online, much of what has been digitized can be accessed at Shambhala International in their teaching library.

Funding

The Shambhala Archives is part of Shambhala International. As such, the archives was able to have a purpose built space allotted to them by Shambhala International but most of their operating budget is funded by donations.[114] Grants also make up a small part of the budget and are usually used for special projects. Supporters of the archives can make a direct donation to the Shambhala Archives or give a portion of their income through Shambhala International.[115] A charitable bequest can also be given to the archives. As of 2006, the Shambhala Archives have an operating budget of around $120,000 a year.[116] Funding for long-term projects like the ARP change over the years. For example, lacking sufficient funds to digitize as much as they wanted with individual donations, the Shambhala Archives began a new funding model for the ARP in 2006, "Individual practice centers, world-wide, were invited to sponsor the project by contributing $3,000 (U.S.) each year for three years, in return for receiving a complete set of CDs (estimated at 1500) including all the recovered, re-mastered audio recordings of these teachings of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche."[117] Like many small independent archives, the Shambhala Archives relies on individual donors to continue to operate. In this regard they have been relatively successful, as continued support has allowed for multiple digitization projects on top of operating costs.

See Also

- Archives - History (Medieval)

- Archives - History (Early Modern)

- LGBTQ Archives

- First Nations Archives

- Archives and Privacy

- Ethics in Archives

References

- ↑ "Religious Archives Survey 2010." The National Archives, UK and Ireland Archives and Record Association and Religious Archives Group, November 1, 2010.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Delva, Melanie. "Faith Archives and Social Justice." Lecture, Archival Systems and the Profession, Vancouver, March 18, 2015.

- ↑ Lambert, James. "Public Archives and Religious Records: Marriage Proposals." Archivaria 1, (1975).

- ↑ "Religious Archives Survey 2010."

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ "Southern Baptist Historical Library & Archives - Baptist Archives, Records and Collections." Southern Baptist Convention. Accessed March 30, 2015. http://www.sbhla.org/coll.htm.

- ↑ The Shambhala Archives. Accessed April 5, 2015. http://www.archives.shambhala.org/index.php.

- ↑ Lambert."Public Archives and Religious Records: Marriage Proposals."

- ↑ Lambert, James. "Toward a Religious Archives Programme for the Public Archives of Canada." Archivaria 3 (1976).

- ↑ "The State of Religious Archives in the UK Today." Religious Archives Group in Association with the National Archives Conference Report, 2007.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Sweeney, Shelley. "Sheep That Have Gone Astray?: Church Record Keeping and the Canadian Archival System." Archivaria 23 (1986).

- ↑ "Religious Archives 2010 Survey."

- ↑ Macquiban, Tim. "Historical Texts or Religious Relics: Towards a Theology of Religious Archives." Journal for the Society of Archivists 16, no. 2 (1995).

- ↑ Hande, D'arcy, and Erich Schultz. "Struggling to Establish a National Identity: The Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada and Its Archives." Archivaria 30 (1990).

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Gard, Robin. "Pastoral Function of Church Archives." Journal of the Society of Archivists 19, no. 1 (1998).

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Archdiocese of Toronto Archives. Accessed January 20, 2015. https://www.archtoronto.org/archives

- ↑ Delva, "Faith-Based Archives and Social Justice."

- ↑ "Religious Archives Survey 2010."

- ↑ Jeff, Gerhardt. “Access to Religious Archives in Public and Private Hands.” Paper presented at the Religious Archives Group Conferene, Manchester, June 2013. http://religiousarchivesgroup.org.uk/conferences/conferences/conference-2012/papers/.

- ↑ "Religious Archives Survey 2010."

- ↑ Archdiocese of Toronto Archives. Accessed January 20, 2015. https://www.archtoronto.org/archives

- ↑ "Religious Archives Survey 2010."

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Sweeney, "Sheep That Have Gone Astray?: Church Record Keeping and the Canadian Archival System."

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ "Religious Archives Survey 2010."

- ↑ Williams, Margaret. “Catholic Archives.” Paper presented at the Religious Archives Group Conferene, London, March 2007. https://religiousarchivesgroup.files.wordpress.com/2012/03/catholic-archives-2007.pdf.

- ↑ Wertheimer, Jack, Debra Bernhardt, and Julie Miller. "Toward the Documentation of Conservative Judaism." American Archivist 57 (1994): 374-79

- ↑ Sweeney, "Sheep That Have Gone Astray?: Church Record Keeping and the Canadian Archival System."

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ "Religious Archives Survey 2010."

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ JAHSENA. Accessed February 20, 2015. http://jahsena.ca.

- ↑ "Religious Archives Survey 2010."

- ↑ "East London Mosque & London Muslim Centre Archive Collections." East London Mosque & London Muslim Centre. Accessed April 7, 2015. http://www.eastlondonmosque.org.uk/content/east-london-mosque-london-muslim-centre-archive-collections.

- ↑ "Religious Archives Survey 2010."

- ↑ Sweeney, "Sheep That Have Gone Astray?: Church Record Keeping and the Canadian Archival System."

- ↑ "Religious Archives Survey 2010."

- ↑ Lambert, "Public Archives and Religious Records: Marriage Proposals."

- ↑ Sweeney, "Sheep That Have Gone Astray?: Church Record Keeping and the Canadian Archival System."

- ↑ Averill, Harold. "The Church, Gays, and Archives." Archivaria 30 (1990): 85-90

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ "Religious Archives Survey 2010."

- ↑ "RAG Guidance." Religious Archives Group. June 23, 2013. Accessed April 5, 2015. http://religiousarchivesgroup.org.uk/advice/rag/.

- ↑ "Archivists and Social Responsibility: A Response to Mark Greene." American Archivist 76, no. 2 (2013): 335-45

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ "The Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission." Parliament of Canada. Accessed April 7, 2015. http://www.parl.gc.ca/content/lop/researchpublications/prb0848-e.htm#A-Creation.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ "Our Mandate." Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC). Accessed April 7, 2015. http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/index.php?p=7.

- ↑ "Canada's Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) Archives | Open Shelf." Open Shelf. Accessed April 7, 2015. http://www.open-shelf.ca/hi5-trc/.

- ↑ Delva, "Faith Archives and Social Justice"

- ↑ News, CBC. "TRC Explores Canada's Archives for First Time." CBCnews. August 6, 2013. Accessed April 7, 2015. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/trc-explores-canada-s-archives-for-first-time-1.1318147.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Montgomery, Bruce. "Fact-Finding by Human Rights Non- Governmental Organizations: Challenges, Strategies, and the Shaping of Archival Evidence." Archivaria 58 (2004): 21-50.

- ↑ Delva, "Faith Archives and Social Justice"

- ↑ Gerhardt. “Access to Religious Archives in Public and Private Hands.”

- ↑ Allen, John. "1962 Document Orders Secrecy in Sex Cases." National Catholic Reporter, August 15, 2003.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Wicks, Linda, and Marc Lerman. "The Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto." Archivaria 30 (1990): 180-84.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ "Archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto." Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto. Accessed March 15, 2015. https://www.archtoronto.org/archives.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ "Hindu Archive Project." The Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies. Accessed March 30, 2015. http://www.ochs.org.uk/research/hindu-archive-project.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ "The State of Religious Archives in the UK Today."

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ JAHSENA. http://jahsena.ca.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ "Edmonton Jewish Cemetery." Accessed March 30, 2015. http://www.edmontonjewishcemetery.ca.

- ↑ JAHSENA. http://jahsena.ca.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ The Shambhala Archives. http://www.archives.shambhala.org/index.php.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid