Course:ARST573/LGBTQ Archives

The mission of LGBTQ archives is to acquire, preserve and provide access to records that document lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and/or queer histories and experiences. An LGBTQ archive can be an independent community or private institution or it can be administered by a larger parent institution, such as a library or university, or by a government agency. Some LGBTQ archives, such as the Transgender Archives at the University of Victoria Libraries Special Collections, form sub-collections within other archives.

Beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, as a response to the broader human rights and gay and lesbian movements that were occurring at the time, as well as to the lack of records that documented the histories and experiences of LGBTQ individuals in mainstream archives, LGBTQ advocates and community members throughout North America began to recognize the value of establishing their own archives. Several LGBTQ archives were established in the 1980s and 1990s in the United Kingdom, Europe, Australia, and Africa.[1] Today, numerous LGBTQ archives exist throughout the world, actively acquiring and preserving the documentary heritage of the LGBTQ community, and providing outreach and advocacy services and resources.

Terminology

While LGBTQ is currently the most commonly used Western initialism to refer to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer community, it is an umbrella term, and cannot fully represent all of the various non-heteronormative sexual orientations and gender identities that exist.[2] LGBTQ, as well as other similar terms and initialisms, has its opponents, for no single term can encompass the richness and complexity that is human sexuality and gender identity. Therefore, there is no single standard or definitive term. Individuals, communities and organizations, including archives, choose to align or label themselves with whichever term they feel they identify. Thus there are a number of LGBTQ terms, a partial list of which is included below.

LGBTQ terms (partial list)

The term a LGBTQ archive identifies itself with can be a reflection of several factors including its mission statement, mandate, acquisition policy, holdings, and patrons, as well as when it was established, the sexual orientation(s) and/or gender identity (identities) of its founder(s) and the broader socio-cultural context of the archive, including any government ministry or larger institution with which it is associated or under which it is administered.

While the name of an archive provides a general sense of what materials the repository acquires and preserves, it is not uncommon for an LGBTQ archive to house materials more wide-ranging and inclusive than their name might suggest. For example, despite its name, the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives (CLGA) acquires, preserves and provides access to materials documenting the experiences and histories of the broader LGBTQ+ community.

History and Development

LGBTQ materials have been collected by individuals for centuries; however, the establishment of formal LGBTQ archival repositories is a relatively recent development worldwide. In North America LGBTQ archives began to be founded in the 1960s and 1970s. Their appearance is often credited to the broader political and cultural changes resulting from the human rights and gay and lesbian movements that were occurring at the time.[3] The impetus behind the establishment of community-based archives is often one of activism, to document and preserve the history of an under-represented community “on their own terms."[4] The lack of representation of LGBTQ individuals in mainstream public or government-funded archives, and the often indirect, biased “official version” of LGBTQ history in public records, spurred LGBTQ-rights advocates and researchers to establish their own specialized repositories dedicated to acquiring and preserving the records of LGBTQ individuals and organizations.[5] The Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives (CLGA) for example was established in 1973 as a direct response to the exclusion of LGBTQ history in university and academic journals, and the suppression, both conscious and unconscious, of LGBTQ materials in mainstream archives.[6] The majority of LGBTQ archives in Canada and the United States, as well as worldwide, were founded in the 1980s and 1990s.[7] As the LGBTQ movement gained greater momentum and visibility in broader society a more favourable environment for the establishment of LGBTQ archives was created.[8]

Many of the LGBTQ archives that exist today started as the personal collections of individuals. As mainstream archives tended not to preserve LGBTQ records, these personal collections were “vital to the saving of queer community history.”[9] Through the interest and efforts of LGBTQ community members and volunteers, several personal collections have been built upon and made publically available as community archives in centralized locations throughout the world.[10]

Today LGBTQ archives are predominantly maintained by volunteers, as well as archivists.[11] Many of the archives retain independence and autonomy from mainstream archives due to distrust based on past injustices to the LGBTQ documentary record, or lack thereof.[12] In the last few decades, due to an explosion of both popular and academic interest in LGBTQ histories, issues and experiences, LGBTQ community archives have expanded in number and extent of holdings, and mainstream archives have begun to acquire more LGBTQ materials.[13]

Materials

LGBTQ archives acquire and preserve records documenting the histories and experiences of the LGBTQ community and its members. Records may include the personal papers of individuals as well as organizational records.

LGBTQ archival materials are of interest to LGBTQ individuals, as well as researchers of human sexuality, gender studies, minority studies, sociology, psychology, medicine, and anthropology. LGBTQ records have also been increasingly used as sources of information for teachers involved in anti-homophobia and LGBTQ awareness educational programs.[14]

Non-Traditional Materials

The archival holdings of LGBTQ archives are often wide-ranging in medium and format.[15] Materials generally include textual records, photographs, publications, audio-visual materials, oral histories, posters, pin-back buttons, clothing, and other objects and ephemera. The absence of LGBTQ records in mainstream archives due to unintentional heterosexism (suppression of LGBTQ records) in the archives and/or records destruction due to society's criminalization and stigmatization of non-heterosexual and non-cisgender individuals made it necessary for those establishing LGBTQ archives to consider ephemera, objects and other materials traditionally not considered archival in nature as records worthy of preservation.[16] In some cases the inclusion of the ephemeral is seen as a form of challenging the historical exclusion of LGBTQ records in mainstream archives.[17] In its early years Les Archives gaies du Québec (AGQ) (The Quebec Gay Archives), for example, placed a priority on acquiring the oldest materials the archivists could find, regardless of format, that documented the LGBTQ experience or had a LGBTQ theme in order to fill some of the gaps in the documentary record.[18] Despite their non-traditional nature, many archivists argue that these records have both evidential and informational value. In fact, it has been posited that due to the lack of preservation of LGBTQ records historically, these non-traditional records have added evidential value and have become like "surrogate records" of past LGBTQ experiences.[19] The Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives (CLGA), for example, considers the objects and ephemera in their holdings, including matchbooks, t-shirts, banners and buttons, as records in their own right and actively collects these materials as they were not and are still currently not likely to be preserved in other repositories for posterity.[20] Furthermore, as LGBTQ life was for so long and still is in some places “transmitted covertly”, ephemera often forms the primary documentation of "queer acts." [21] Some scholars, such as Ann Cvetkovich, argue that ephemera is a necessary component in LGBTQ archives due to the part these materials play in LGBTQ activism. Banners, t-shirts and buttons created for LGBTQ activism events are often evidence of the experiences of these events, as well as of the emotions (pride, anger, grief, shame and fear) that are central to the parades, festivals, protests and movements.[22]

LGBTQ archives acquire non-traditional archival materials that were historically unwanted by mainstream public and university archives also simply in order to meet the needs of their researchers. Community-based archives often acquire objects, books, ephemera, and clothing, as well as the more traditional archival materials of photographs, textual records and audio-visual materials.[23] As the majority of LGBTQ archives are community-based archives, materials are often collected if they are “deemed important to community members, regardless of format."[24] Furthermore, for many LGBTQ archives acquisitions are largely fuelled by donations so what is deemed relevant and worthy of preservation by the community they serve is usually accepted into the archive.[25]

In some cases, the materials a LGBTQ archive acquires is due to the influence and precedent set by the archives' founders. As it was not uncommon in the past for an LGBTQ archive to be formed through the personal collection of one or two individuals, ephemera and objects found their way early into the foundation of many of these archives.[26]

Records of Human Sexuality

Records documenting human sexuality have been acquired and preserved in archives, libraries and museums for centuries; however, those documenting non-heteronormative sexualities are often missing.[27] Due to this lack of representation, many LGBTQ archives acquire materials dealing directly with sexuality, such as works of erotica and pornography, in order to preserve affirming, empowering and positive images of LGBTQ sexualities, challenge negative stereotypes and make it possible to trace societal attitudes towards non-heteronormative sexuality.[28] The Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives (CLGA), for example, actively acquires gay male pornography and erotica.[29]

Oral History

Oral histories are increasingly being created and collected by LGBTQ archives worldwide. Oral history as a medium has become central to the reclaiming of LGBTQ individuals' histories and experiences due to the past suppression and silencing of their records and voices, as well as the historical stigmatization and criminalization of LGBTQ sexualities.[30] Due to the loss of a significant portion of older materials, oral history has become a method used by several LGBTQ archives for writing LGBTQ "experiences into existence", as well as a method of challenging the heterosexism of traditional history that is predominant in mainstream archives.[31]

Other Records

While LGBTQ archives focus on collecting the records of LGBTQ individuals and organizations, due to the historical criminalization and stigmatization of non-heteronormative sexuality the following more traditional archival records often document LGBTQ histories and experiences and therefore may also be actively acquired by LGBTQ archives: court records, newspapers, sexual literature, and the records of hospitals, asylums, reformatories, boarding-houses, and women’s colleges.[32]

Access

An archives’ accessibility will depend on a variety of factors, including whether or not it is a private or public institution, as well as the availability of the archivist(s). While the majority of LGBTQ archives are open to the public, some archives are focused on specifically providing access to LGBTQ community members. The Lesbian Herstory Archives in Brooklyn, New York for example is primarily aimed at serving lesbians.[33]

Outreach and Activism

The majority of LGBTQ archives throughout the world attach great importance to outreach activities and activism. Due to the persistence of both homophobia and transphobia in broader society, these outreach and activist activities aim at challenging discrimination and bringing awareness to LGBTQ issues, experiences, and history.[34] Much of the public programming sponsored by LGBTQ archives is related to the issues of identity and pride, issues which are often central to the mandate of these archives.[35] The outreach activities of LGBTQ archives also provide an outlet for the historically silenced voices of LGBTQ individuals and help raise awareness of difficult subject matters, such as the AIDS epidemic.[36] Les Archives gaies du Québec (AGQ) (The Quebec Gay Archives), for example, contributes to LGBTQ events, such as festivals, conferences and parades, publishes books and a regular newsletter (L'Archigai), organizes exhibitions of archival materials, and works with other organizations in raising awareness of LGBTQ experiences and history.[37] The outreach activities of Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action (Gay and Lesbian Archives (GALA) of South Africa) serve as an activist response to the endurance, and in some countries, criminalization of homophobia in Africa.[38] GALA not only preserves LGBTQ records but also encourages "ongoing knowledge production and dissemination" by commissioning research projects and publications to "enhance understanding of LGBTIQ issues." [39] All research projects and publications are selected to compliment and expand upon the materials in the archives' collection. Past research projects have explored the experiences of LGBTQ individuals in the South African military, gender identity for traditional African healers who are in same-sex relationships, and homosexuality and homophobia in South African secondary schools. [40] The Gay and Lesbian Archives of the Pacific Northwest (GLAPN) partners with Portland's Q Center, a LGBTQ community centre, to produce the "Our Stories Series," a variety of LGBTQ events, often centered around oral history and storytelling. These events aim to create new records (many of the events are recorded) of the stories of LGBTQ activists and elders on significant anniversaries and issues, and to further disseminate this information to the public.[41] The June Mazer Lesbian Archives holds a number of events each year, including tours of the archives and an annual open house, designed to engage the lesbian community and the broader public.[42]

Challenges

Lack of Funding

Like most community-based archives, LGBTQ archives often rely solely on the financial support of the community they serve. Funding is raised through fundraising efforts; collaboration with other archives, LGBTQ organizations and associations; outreach services; and donations from the public.[43] Due to a lack of funds many archives must also rely heavily on the work of volunteers. Collections are predominantly built with donations of materials from the community, as acquisition budgets are often limited.[44] The majority of LGBTQ archives choose to remain completely autonomous, not applying for or accepting financial support from government agencies and mainstream financial institutions, due in part to the importance of activism in most of the archives, as well as past and present societal and institutional discrimination. The Lesbian Herstory Archives, for example, aspires to a high level of independence, accepting financial support solely from the lesbian community and LGBTQ supporters.[45]

Barriers to Access

As is the case with many archives, LGBTQ archives face increasing backlogs of unprocessed archival materials due to a lack of funding and staffing. As backlogs grow, access to archival materials is reduced.[46]

For LGBTQ archives housed and administered within non-LGBTQ parent institutions, providing access to LGBTQ researchers and materials can be especially challenging. While efforts have been made in the archival profession by LGBTQ roundtables and working groups to improve accessibility through the development of workshops and information resources, problems with environmental accessibility and descriptive terminology still exist.[47]

A welcoming, physical environment greatly affects the level of access a LGBTQ researcher feels they have in an archive. Environmental cues in an archive’s reading room and building can indicate that LGBTQ researchers are welcome, from exhibits and images of LGBTQ people in the reading room to single-user and/or gender-neutral bathrooms. Multi-person, female/male sex-segregated bathrooms in buildings that house an LGBTQ archive can indicate to transgender researchers that the archives are not committed to providing access and can make long research sessions with the archival materials either impossible, or at the very least, a stressful experience.[48] The handbook Opening the Door to the Inclusion of Transgender People published by the National LGBTQ Task Force and the National Center for Transgender Equality provides ways organizations can consciously change their spaces to be transgender inclusive.[49]

The verbal environment of an archive can also have a great effect on its provision of access to LGBTQ researchers. Considering the pervasive discrimination experienced by LGBTQ people in broader society today, tension and fear exists for many LGBTQ researchers when requesting materials and photocopying services from archives’ staff, as it may reveal one’s sexuality or status as a non-cisgender person.[50] The use of pronouns and any assumptions made by the archive’s staff can also make accessing the materials a distressing and unwelcoming experience for transgender researchers.[51] The language used in archival descriptions and finding aids can also marginalize, exclude and misrepresent both LGBTQ researchers and the creator(s) of the records if inaccurate, out-dated, and inappropriate terminology is used. The relative youth of several LGBTQ terms, as well as the evolving nature of language, can make it difficult for archives to adapt to linguistic changes.[52] The Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) have been slow to adapt to some of the most current and accepted terminology, including “bisexuals” (adopted in 1993), “transgender people” and “transgenderism” (both adopted in 2007).[53] In order to provide accurate and sensitive descriptions, and provide the best access to LGBTQ materials and researchers, as an act of activism, some archives have collaborated with their communities and developed their own descriptive standards and subject headings.[54]

LGBTQ Archives and the Profession

Archivists

Small community-based LGBTQ archives tend to be managed by non-professional archivists. The majority of LGBTQ archives that are housed within other institutions, such as a university archive, or those whose focus is on the national level, such as the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives (CLGA), however, tend to employ archivists with archival training. Resources such as the support of the The Lesbian and Gay Archives Roundtable (LAGAR) have been developed to help community-based LGBTQ archives with information about archival best practices and methods.[55]

Professional Interest and Support

Since the late 1980s there has been a growing interest in the preservation of LGBTQ history and records in the archival profession. In 1989, The Lesbian and Gay Archives Roundtable (LAGAR) was founded by members of the Society of American Archivists (SAA) in order to promote the preservation of and access to records documenting LGBTQ history. The roundtable also serves as a liaison between American LGBTQ archives and the SAA.[56] In 2009, the journal of the Association of Canadian Archivists (ACA) Archivaria published a special section on "Queer Archives" (Archivaria #68). A session entitled "Perfect Pairings? LGBT Archives and the Academy" was held at the 39th ACA Annual Conference in Victoria, British Columbia. The organization New England Archivists (NEA) established the LGBTQ Issues Roundtable, which runs a blog "Queer!NEA" that regularly posts on LGBTQ issues and history.

Case Studies

The Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives (CLGA)

The Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives (CLGA) is both the largest independent LGBTQ archive, and the second largest LGBTQ archive, in the world.[57] The archive acquires, preserves, and provides public access to LGBTQ archival materials in order to fulfill their mission of being “a significant resource and catalyst for those who strive for a future world where lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgendered people are accepted, valued, and celebrated.”[58] The archive’s collection, which primarily focuses on Canada, consists of personal and organizational records, over 2,000 hours and 1,300 items of audio recordings; over 600 moving images; artifacts, including pin-back buttons, t-shirts, and banners; artwork; more than 7,000 photographs; over 1,500 posters; over 5,300 vertical files compiled by CLGA on LGBTQ individuals, groups and events; several thousand newspapers; and the world’s largest LGBTQ library and collection of lesbian and gay periodicals.[59] Prompted by the lack of representation of LGBTQ individuals in mainstream museums, libraries and archives, from its establishment CLGA has followed a total archives approach to acquisition, collecting a range of materials in a variety of formats.[60]

CLGA was established in 1973 in Toronto, Ontario, Canada by the editorial collective of the LGBTQ magazine The Body Politic (TBP), the “most important gay liberation magazine in the English-speaking world.”[61] In the first few years of its existence the archive's collection primarily consisted of the records of TBP. However, with the support of the magazine, which advertised the archive and solicited donations, the archive was able to expand their collection, acquiring the records of numerous LGBTQ individuals and organizations.[62] Originally named the Canadian Gay Liberation Movement Archives, the archive changed its name to the Canadian Gay Archives in 1975. In 1993, in an effort to be more inclusive, the archive adopted its current name.[63] In 2005 the archive moved from its original location on Temperance Street in downtown Toronto to a temporary location in the city on Wellesley Street in the Church and Wellesley gay village. In 2009 CLGA moved into its current location, a house built in 1858, at 34 Isabella Street in the same neighbourhood.[64]

CLGA is dedicated to providing outreach and access to its materials, as well as disseminating information about the LGBTQ community. The archive takes part in the Government of Ontario’s anti-homophobia educational programs, presenting and exhibiting on Canadian LGBTQ history, as well as providing teachers with information relevant to the programs.[65] In 1998, the archive established its National Portrait Collection, a permanent display located throughout the archive’s space of over forty portraits honouring individuals who have made significant contributions to LGBTQ life in Canada.[66] The archive produces a monthly newsletter, a blog, and a series of posts on their website entitled “What’s in the Archives?” all of which serve to highlight LGBTQ history, the collection, and the work of the archives. CLGA is also currently working on producing a three-volume publication that will feature the stories of LGBTQ individuals “who challenged fear and discrimination to establish Canada’s thriving and diverse LGBTTIQQ2SA culture.”[67]

CLGA is an independent archive, and receives financial support through public donations and fundraising.[68] Due to its non-profit status and lack of government financial support, CLGA charges researchers fees to use the archive.[69] The archive has a small staff and large volunteer base, headed by an archivist. CLGA is open to the public Tuesday through Thursday from 7:30 pm to 10 pm, and Friday from 1 pm to 5 pm.[70]

IHLIA LGBT Heritage Archive

IHLIA LGBT Heritage is Europe’s largest archive and information centre of homosexual, lesbian, bisexual and transgender archival materials and publications. Located in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, their mission is to acquire and make accessible materials relevant to the LGBTQ community, in order to “keep LGBT history alive,” to “promote the social acceptance of LGBTs” and to “contribute to a balanced image of the entire society and to social well-being.” [71] IHLIA is comprised of an archive of 314 feet, which includes personal and organizational records, photographs, audio-visual materials, ephemera and objects (such as posters, t-shirts, buttons and condom packages), and a collection of over 22,000 books, 4,800 magazines and journals, 11,000 items of grey literature, and 2,000 videos and DVDs.[72]

IHLIA was founded as the International Homo/Lesbian Information Center and Archive (IHLIA) in 1999 with the merging of the Homodok (Documentation Centre of Gay Studies, established in 1978), the Lesbian Archives of Amsterdam (established in 1983) and the Anna Blaman House (formerly the Lesbian Archives in Leeuwarden, established in 1982). In 2007 IHLIA moved to its current location on the sixth floor of Amsterdam Public Library (OBA).[73] Since the move, the less requested and more fragile books and the archival records are stored at the International Institute of Social History (IISH) in Amsterdam.[74] To use IHLIA’s archival materials researchers must request materials well ahead of their visit, as IISH requires permission for access.[75] Fonds level descriptions of the archival materials can be searched online through IHLIA’s database. A digital collection of their materials is available for use in the reading room.[76]

IHLIA is dedicated to providing outreach, taking part in LGBTQ activist events and disseminating information about the community. They hold regular exhibitions of their materials and take part in LGBTQ symposiums and conferences. IHLIA created and hosts The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans & Intersex – Archive, Library, Museum and Special Collections (LGBTI-ALMS) conference. The conference aims to bring together European, North American and international society and heritage institutions to make the history of LGBTI people more accessible and visible.[77] IHLIA also runs the project “Open Up!” which focuses on the history of LGBTQ emancipation and development, specifically in those European countries in which LGBTQ rights are still significantly suppressed. The purpose of the project is to make a large number of archival documents, predominantly textual records, including meeting minutes, memos, policy papers, newsletters, and lecture notes, as well as journals, newspapers, and magazines, digitally available online.[78]

IHLIA is an independent archive, and receives financial support through public donations and government grants. The institution has a large staff and volunteer base, headed by an archivist/librarian. The central location is open Monday through Thursday from 12 to 5 pm.[79]

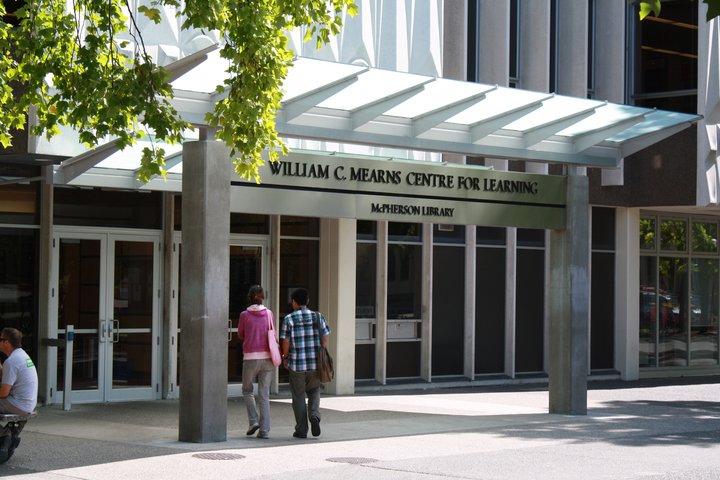

The Transgender Archives

The Transgender Archives at the University of Victoria Libraries Special Collections in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada is the largest transgender archive in the world.[80] The archives forms a sub-collection of the archival collection of Special Collections. Their mission is to preserve the history of trans* (Special Collections' preferred term) people and “pioneering activists, community leaders, and researchers who have contributed to the betterment of transgender people” and to promote “understanding of trans* people and their rights."[81] The archives’ fonds and collections represent seventeen countries and over a century of trans* activism and research. The archives consists of over 320 linear feet (98 metres) of archival materials and includes personal papers and organizational records, books and periodicals, audio-visual materials, photographs, and a range of ephemeral materials, such as posters, newspaper clippings, postcards, greeting cards, drawings, paintings, t-shirts and objects.[82]

UVic Special Collections has been actively acquiring publications, ephemera and textual documents of individuals and organizations involved with transgender activism since 2007. The Transgender Archives was formally established in 2005 with the donation of the Rikki Swin Institute collection. The archives has been further expanded and enhanced by several other significant donations, including the personal papers of Reed Erickson, deceased founder and president of the Erickson Educational Foundation, and the records of the University of Ulster Trans-Gender Archive, among others.[83] Donations are co-ordinated by the archives Founder and Academic Director, Dr. Aaron Devor, and are managed by the Director of Special Collections and University Archivist.[84]

The Transgender Archives is devoted to providing access to its materials and to the widespread dissemination of trans* history and information. The archives is currently fundraising to digitize the archives’ holdings for online access. The archives aims to share their materials, adding to the growing collection of trans* resources online, in order to promote trans* awareness and understanding. As funding permits, digital copies of key documents are currently being uploaded and made available on the archives’ website.[85] In March 2014, the archives organized and hosted an international symposium on transgender archives, research and activism entitled “Moving Trans* History Forward." The three-day symposium, that brought together scholars, researchers, activists, educators, community members and allies, was one of the archives' steps towards its goal of creating “a safer and more just world."[86]

Special Collections is a public university repository and shares facilities and responsibilities with the University Archives. The Transgender Archives is accessible to the public, as well as the university’s faculty, students, and scholars, for research and exploration.[87] Special Collections has a small permanent staff of archivists and librarians. They also regularly employ graduate student archival assistants from university archival programs to aid in the processing of their backlogged materials. Special Collections is open Monday through Friday, from 8:30 am to 4:30 pm (September-April), 10:30 am to 4:30 pm (May-August).[88]

Partial List of LGBTQ Archives

The following list is by no means complete. A more comprehensive list of repositories that hold significant archival collections of LGBTQ materials in North America, including significant collections found within non-LGBTQ archives, libraries and special collections, can be found in the guide Lavender Legacies published by the Lesbian and Gay Archives Roundtable (LAGAR) of the Society of American Archivists (SAA).

Canada

Les Archives gaies du Québec (AGQ) (The Quebec Gay Archives)

Archives of Lesbian Oral Testimony

The Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives (CLGA)

Manitoba Gay and Lesbian Archives

Transgender Archives, University of Victoria

United States

Gay and Lesbian Archive of Mid-America (GLAMA)

Gay and Lesbian Archives of the Pacific Northwest

Gerber/Hart Library and Archives

Gulf Coast Archive and Museum of GLBT, Inc.

The John J. Wilcox, Jr. LGBT Archives

Lambda Archives of San Diego (LASD)

The Latino GLBT History Project’s Archival Collection

The LGBT Community Centre National History Archive

ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives

Stonewall National Museum and Archives

Transgender Archive, Transgender Foundation of America

United Kingdom

The Hall-Carpenter Archives (HCA)

Lesbian and Gay Newsmedia Archive (LAGNA)

Europe

Archives Recherches Cultures Lesbiennes (ARCL)

Centrum Schwule Geschichte Köln Archive

Fonds Suzan Daniel Gay/Lesbian Archives and Documentation Centre

Gay and Lesbian Academy Archives

Africa

Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action (Gay and Lesbian Archives (GALA) of South Africa)

Australia

The Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives (ALGA)

New Zealand

Lesbian and Gay Archives of New Zealand (LAGANZ) (Te Pūranga Takatāpui o Aotearoa)

Further Reading

- Barriault, Marcel. "Archiving the Queer and Queering the Archives: A Case Study of the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives (CLGA)." In Community Archives: The Shaping of Memory, edited by Jeannette A. Bastian, and Ben Alexander, 97-108. London: Facet Publishing, 2009.

- Fullwood, Steven G. "Always Queer, Always Here: Creating the Black Gay and Lesbian Archive in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture." In Community Archives: The Shaping of Memory, edited by Jeannette A. Bastian, and Ben Alexander, 235-250. London: Facet Publishing, 2009.

- Greenblatt, Ellen, ed. Serving LGBTIQ Library and Archives Users: Essays on Outreach, Service, Collections and Access. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2011.

- Johnson, Matt. “Transgender Subject Access: History and Current Practice.” Cataloging & Classification Quarterly 48 (2010): 661‐683.

- Larade, Sharon P., and Johanne Pelletier. “Mediating in a Neutral Environment: Gender-Inclusive or Neutral Language in Archival Description.” Archivaria 35 (1993): 99-109.

- The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) Religious Archives Network. Accessed March 30, 2015. http://www.lgbtran.org/.

- Wexelbaum, Rachel, ed. Queers Online: LGBT Digital Practices in Libraries, Archives, and Museums. Sacramento: Litwin Books, 2015.

- X, Ajamu, Topher Campbell, and Mary Stevens. “Love and Lubrication in the Archives or rukus!: A Black Queer Archive for the United Kingdom.” Archivaria 68 (2009): 271-294.

See Also

References

- ↑ Barriault, Marcel. "Hard to Dismiss: The Archival Value of Gay Male Erotica and Pornography." Archivaria 68 (2009): 224.

- ↑ Wakimoto, Diana K., Christine Bruce, and Helen Partridge. "Archivist as Activist: Lessons from Three Queer Community Archives in California." Archival Science 13 (2013): 294, accessed February 20, 2015, doi: 10.1007/s10502-013-9201-1.

- ↑ Barriault. "Hard to Dismiss," 224.

- ↑ Flinn, Andrew, Mary Stevens, and Elizabeth Shepherd. “Whose Memories, Whose Archives? Independent Community Archives, Autonomy and the Mainstream.” Archival Science 9 (2009): 73, accessed February 18, 2015, doi: 10.1007/s10502-009-9105-2.

- ↑ Barriault. "Hard to Dismiss," 225.

- ↑ Maynard, Steven. “‘The Burning, Wilful Evidence’: Lesbian/Gay History and Archival Research.” Archivaria 33 (1991-92): 196.

- ↑ Lukenbill, Bill. “Modern Gay and Lesbian Libraries and Archives in North America: A Study in Community Identity and Affirmation.” Library Management 23 (2002): 97.

- ↑ Wakimoto, Bruce, and Partridge, "Archivist as Activist," 307.

- ↑ Wakimoto, Bruce, and Partridge, "Archivist as Activist," 307.

- ↑ Wakimoto, Bruce, and Partridge, "Archivist as Activist," 299.

- ↑ Wakimoto, Bruce, and Partridge, "Archivist as Activist," 294.

- ↑ Flinn, Stevens, and Shepherd, "Whose Memories," 71.

- ↑ Zieman, Kate. “Youth Outreach Initiatives at the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives.” Archivaria 68 (2009): 313.

- ↑ Zieman, "Youth Outreach Initiatives," 311.

- ↑ Lukenbill, “Modern Gay and Lesbian Libraries and Archives," 98.

- ↑ Barriault, "Hard to Dismiss," 220.

- ↑ Chenier, Elise. “Hidden from Histories: Preserving Lesbian Oral History in Canada.” Archivaria 68 (2009): 258.

- ↑ Prince, Jacques. “Du placard à l’institution: l’histoire des Archives gaies du Québec (AGQ).” Archivaria 68 (2009): 296.

- ↑ Barriault, "Hard to Dismiss," 220.

- ↑ Zieman, "Youth Outreach Initiatives," 313.

- ↑ Danbolt, Mathias. "We're Here! We're Queer?: Activist Archives and Archival Activism" Lambda Nordica 3-4 (2010): 94-95.

- ↑ Danbolt, "We're Here!" 96.

- ↑ Flinn, Stevens, and Shepherd, "Whose Memories," 74.

- ↑ Wakimoto, Bruce, and Partridge, "Archivist as Activist," 305.

- ↑ Wakimoto, Bruce, and Partridge, "Archivist as Activist," 306.

- ↑ Flinn, Stevens, and Shepherd, "Whose Memories," 80.

- ↑ Barriault, "Hard to Dismiss," 227.

- ↑ Barriault, "Hard to Dismiss," 246.

- ↑ Barriault, "Hard to Dismiss," 222.

- ↑ Maynard, "Burning, Wilful Evidence," 197.

- ↑ Chenier, "Hidden from Histories," 252.

- ↑ Maynard, "Burning, Wilful Evidence," 199.

- ↑ Lesbian Herstory Archives. "Using the Archives." Accessed March 10, 2015. http://www.lesbianherstoryarchives.org/using.html.

- ↑ Wakimoto, Bruce, and Partridge, "Archivist as Activist," 295.

- ↑ Wakimoto, Bruce, and Partridge, "Archivist as Activist," 305.

- ↑ Prince, "Du placard à l’institution," 306.

- ↑ Prince, "Du placard à l’institution," 304.

- ↑ Manion, Anthony, and Ruth Morgan. “The Gay and Lesbian Archives: Documenting Same-Sexuality in an African Context.” Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity 67 (2006): 35.

- ↑ Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action (GALA). "Research." Accessed March 30, 2015. http://www.gala.co.za/archives_research/research.htm.

- ↑ GALA. "Research." Accessed March 30, 2015. http://www.gala.co.za/archives_research/research.htm.

- ↑ Gay and Lesbian Archives of the Pacific Northwest (GLAPN). "The Our Stories Series." Accessed March 28, 2015. http://www.glapn.org/1003ourstories.html.

- ↑ June Mazer Lesbian Archives. "Events." Accessed March 30, 2015. http://www.mazerlesbianarchives.org/category/events/.

- ↑ Prince, "Du placard à l’institution," 308.

- ↑ Flinn, Stevens, and Shepherd, "Whose Memories," 80.

- ↑ Flinn, Stevens, and Shepherd, "Whose Memories," 82.

- ↑ Lukenbill, “Modern Gay and Lesbian Libraries and Archives," 98.

- ↑ Rawson, K.J. “Accessing Transgender // Desiring Queer(er?) Archival Logics.” Archivaria 68 (2009): 124.

- ↑ Rawson. “Accessing Transgender," 127.

- ↑ Mottet, Lisa, and Justin Tanis. Opening the Door to the Inclusion of Transgender People. New York: National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute and National Center for Transgender Equality, 2008.

- ↑ Maynard, "Burning, Wilful Evidence," 197.

- ↑ Rawson. “Accessing Transgender," 133.

- ↑ Rawson. “Accessing Transgender," 125.

- ↑ Wakimoto, Bruce, and Partridge, "Archivist as Activist," 310.

- ↑ Wakimoto, Bruce, and Partridge, "Archivist as Activist," 310.

- ↑ Society of American Archivists. "The Lesbian and Gay Archives Roundtable (LAGAR)." Accessed March 13, 2015. http://www2.archivists.org/groups/lesbian-and-gay-archives-roundtable-lagar.

- ↑ "LAGAR."

- ↑ Zieman, "Youth Outreach Initiatives," 313.

- ↑ Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives. "About Us." Accessed April 5, 2015. http://www.clga.ca/about-us.

- ↑ CLGA. "Collections." Accessed April 5, 2015. http://www.clga.ca/collections-main.

- ↑ Barriault, "Hard to Dismiss," 226.

- ↑ Chenier, "Hidden from Histories," 255.

- ↑ Zieman, "Youth Outreach Initiatives," 312.

- ↑ Chenier, "Hidden from Histories," 255.

- ↑ CLGA. "About Us." Accessed April 5, 2015. http://www.clga.ca/about-us.

- ↑ Zieman, "Youth Outreach Initiatives," 311.

- ↑ CLGA. "Exhibitions." Accessed April 5, 2015. http://www.clga.ca/exhibitions/current.

- ↑ CLGA. "Stories Project Blog Launched."Accessed April 5, 2015. http://www.clga.ca/stories-project-blog-launched.

- ↑ CLGA. "Donate." Accessed April 5, 2015. http://www.clga.ca/donate.

- ↑ CLGA. "Research." Accessed April 5, 2015. http://www.clga.ca/fee-schedule.

- ↑ CLGA. "Contact Us." Accessed April 5, 2015. http://www.clga.ca/contact-us.

- ↑ IHLIA. "About Us." Accessed March 24, 2015. http://www.ihlia.nl/informatiebalie/over-ons/.

- ↑ IHLIA. "FAQ." Accessed March 24, 2015. http://www.ihlia.nl/information-desk/faq/?lang=en.

- ↑ IHLIA. "Timeline." Accessed March 24, 2015. http://www.ihlia.nl/information-desk/timeline/?lang=en.

- ↑ IHLIA. "IISH." Accessed March 24, 2015. http://www.ihlia.nl/collectie/iisg/.

- ↑ IHLIA. "FAQ." Accessed March 24, 2015. http://www.ihlia.nl/information-desk/faq/?lang=en.

- ↑ IHLIA. "FAQ." Accessed March 24, 2015. http://www.ihlia.nl/information-desk/faq/?lang=en.

- ↑ IHLIA. "Timeline." Accessed March 24, 2015. http://www.ihlia.nl/information-desk/timeline/?lang=en.

- ↑ IHLIA. "Open Up!" Accessed March 24, 2015. http://www.ihlia.nl/collectie/open-up/.

- ↑ IHLIA. "About Us." Accessed March 24, 2015. http://www.ihlia.nl/informatiebalie/over-ons/.

- ↑ Wilson, Lara. Introduction to The Transgender Archives: Foundations for the Future, by Aaron H. Devor. Victoria: University of Victoria Libraries, 2014, ix.

- ↑ Wilson, introduction, x.

- ↑ Devor, Aaron H. The Transgender Archives: Foundations for the Future. Victoria: University of Victoria Libraries, 2014, 25-37.

- ↑ Devor, Aaron H. "Preserving the Footprints of Transgender Activism: The Transgender Archives at the University of Victoria." QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking 1 (2014): 202.

- ↑ University of Victoria Libraries Transgender Archives. "Transgender Archives." Accessed March 25, 2015. http://transgenderarchives.uvic.ca/.

- ↑ Devor, "Preserving the Footprints," 202.

- ↑ University of Victoria Libraries Transgender Archives. "Symposium." Accessed March 25, 2015. http://transgenderarchives.uvic.ca/symposium.

- ↑ Devor, "Preserving the Footprints," 202.

- ↑ University of Victoria Libraries. "About Special Collections." Accessed March 25, 2015. http://www.uvic.ca/library/locations/home/spcoll/about/index.php.