Course:ARST573/Ethics in Archives

Archival ethics is an area of thought in archives regarding the moral responsibilities of archivists. The topic of ethics in archives seeks to explain the obligations of archivists not only in the records or their institutions, but in society at large. Discussions on archival ethics have been prompted by the establishment of professional organizations and codes that govern archival practive and in an attempt to provide direction for archivists and define the moral obligations of archivists. Additionally, ethical discussions on the nature of archives have resulted in discussions on the role of archives in social justice.

Aspects of Archival Ethics

Archival ethics is not a single topic so much as many topics that combine to form a broad area of study. In general, there is no clear consensus on what specifically comprises archival ethics. [1] In the words of Glenn Dingwall “ethics is a branch of philosophy that attempts to evaluate the morality of behaviors and actions.” [2] Merriam Webster defines ethics (or ethic) broadly as "a set of moral principles"[3] and this broadness allows for the inclusion of many topics. These topics can be broken down into three primary aspects. These aspects are Professionalism, which deals with the establishment of professional organizations and attempts to establish archivists as professions that are governed by rules, Ethical Codes, which attempt to provide guidance to archivists on how to make decisions while practicing, Social Justice, which discusses the moral obligations of archivists to members of society (often those who are disenfranchised). These aspects have been discussed in length by a number of notable scholars.

Professionalism

Ethics is a concept that is strongly rooted in professionalism.[4] Some even believe that professions are inherently ethical practices because of the service orientation which is inherent to them.[5] In essence, professions pledge to carry out its services for the benefit of its clients and not for itself, and the clients trust that the profession will do this because of the inherently ethical nature of a profession that exists for service.[6] According to Dingwall who is explaining Daryl Koehn’s model of evaluating professionalism “the public's acceptance of this pledge is contingent on the knowledge that the professional can be trusted to perform his or her duties in a manner that furthers the client's best interest.”[7] Dingwall classifies archivists as being in the middle of the spectrum of professionalism and he cites Richard Cox as pointing out three areas in which archivists have a weak professional claim.[8] Dingwall says “These areas are the level of development of archival theory, the degree of public sanction given to archivists, and the commitment of the archival community to institutionalized altruism.” [9] Dingwall focuses particularly on the amount of public trust archivists receive and cites this as to why a strongly developed code of ethics is important to archivists.[10] He indicates that “while archivists may believe that the tasks we perform are motivated out of concern for a greater public good, the public may or may not share that belief.”[11] Dingwall believes that a strong code of ethics will increase this trust.[12]

Ethical Codes

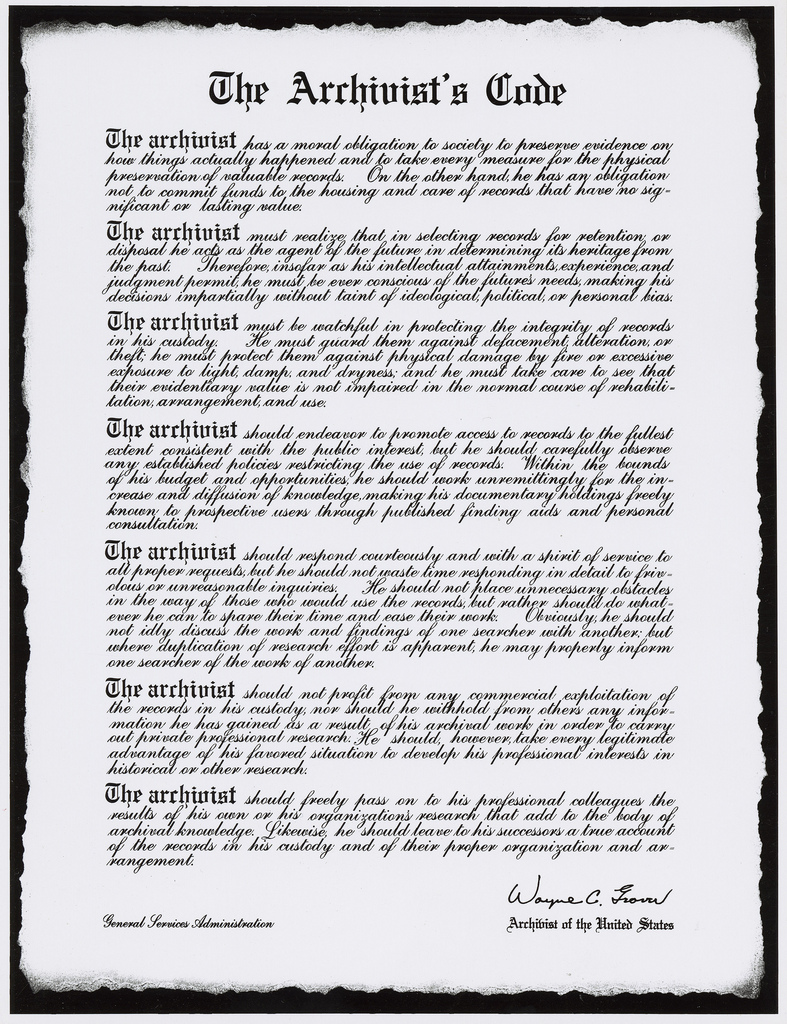

Ethical codes are codes established by professional organizations to provide governance and guidance for the professionals in the field.[13] These codes were developed to define for archivists the responsibilities they have to the public and to the records they preserve and are constructed from multiple moral philosophical perspectives as well as input from the professional community.[14] According to Glenn Dingwall "The ultimate goal of such a code is to provide a framework that allows the individual practitioner to devise an ethical course of action in the face of what often prove to be novel situations." [15] Despite this, ethical codes are not meant to be followed without question[16], in fact as Dingwall says “The issuance of a code from a position of authority is reason to be all the more critical of it.” [17] They were also established in part to add legitimacy to the profession and allow it to be seen as trust worthy.[18] Archivists’ ethical codes date prior to the establishment of professional associations.[19] The United States, for example, had its first code written by what was then the National Archives.[20] This code was called the Archivist's Codes and it was meant to be displayed in archivists' offices to provide moral and legal guidance.[21] The Archivist's Code was originally printed in the American Archivist in 1955 to be used in training programs for national archivists of the United States of America.[22] The code was criticized for being too moralistic but it was considered a good start in guiding the professional judgements of archivists.[23]

By the 1970s in the United States, the need for a new ethical code was recognized.[24] In 1976 the SAA Council appointed a committee to write a new code of ethics.[25] The committee was given two tasks: 1) to prepare a draft code of ethics for the profession,and 2) to make recommendations to the Council on the appropriateness and feasibility of the Society adopting sanctions against unethical actions."[26] This process was completed in three years, with the final product being presented in 1980.[27] The product that was produced was intended to be a series of judgments to guide professional decisions that could be changed as needed.[28] This professional code has since seen several iterations, with the last being a 2012 update.[29] The Society of American Archivists was not the only professional organization to develop a code of ethics, numerous other organizations including the Association of Canadian Archivists[30] and the International Council of Archives[31] have also developed their own codes.

A number of experts have accused these codes of being too weak to provide significant guidance to archivists and other records professionals. Archival codes of ethics, Richard Cox points out, provide almost no guidance to archivists on what their obligations to a corporate employer actually are. [32] He questions where the line between being an employee of a company, tasked with helping that company achieve its bottom line, and being a professional with ethical responsibilities is drawn. [33] Nowhere in the codes of ethics provided to archivists do they help archivists to determine when they, with their increased access to the records of an organization, should be whistle blowers. [34] Mary Neazor points out some of the weaker aspects of archival codes of ethics and summarizes them as being open ended and ineffective. Neazor states that “some appear to be so near to simple codes of archival practice that they could even fit comfortably into an overtly oppressive political and social context, while others include statements of which one element could cancel another out, or which could, in practice, give rise to near-insoluble dilemmas.” [35] Because of this, codes of ethics have been called upon to be revised and improved. This is important because, as Glenn Dingwall points out, public trust in archives does not come from the simple fact that codes of ethics exist, but from an ethically guided profession.[36]

Common Themes

Many archival codes of ethics share common themes. One of the most dominant themes in the codes of ethics is the duty of archivists to protect the integrity of the records that are in their possession.[37][38][39] Another common theme in codes of ethics is a commitment to the professional community. The Association of Canadian Archivists emphasizes the importance of contributing to the profession and not competing with colleagues in a way that would endanger records.[40] The Society of American Archivists Code of Ethics stats that archivists should collaborate with colleagues.[41] Other common themes include a sense of service, with archivists personal endeavors, such as personal acquisition of records and personal research, not coming above their duty as archivists and being transparent.[42][43][44]

Examples of Codes of Ethics

Association of Canadian Archivists Code of Ethics

Society of American Archivists Code of Ethics

International Council on Archives

Australian Society of Archivists

Social Justice

Archival ethics are often associated with social justice because of the ability of archives to serve as a source of accountability from the powerful for the social injustices of the past.[45] [46] [47] The traditional opinion on the conduct of archivists was that archivists as professionals could and should be wholly neutral in the work that they do, merely acquiring and preserving records of importance an exercising no influence on the way the future remembers the past. [48] This idea has been called into question by both members and non-members of the profession who believe that archivists have inherent power in their work. [49] [50] [51] These commentators have called on archivists to acknowledge the inherent power of archives and the power they wield as a result. [52] [53] Verne Harris in particular encourages archivists to acknowledge this, to fear and respect the concept of otherness in archives.[54]

Major Contributors

There have been many proponents of ethics in archives that have helped to establish dominant lines of thought in the area. Three major contributors to the discussion have been Howard Zinn, Randall Jimerson, and Verne Harris. These scholars have written extensively on the obligations of archivists to acknowledge the inherent social power in what they do and to move away from the traditional notion of the impartial custodian of records.

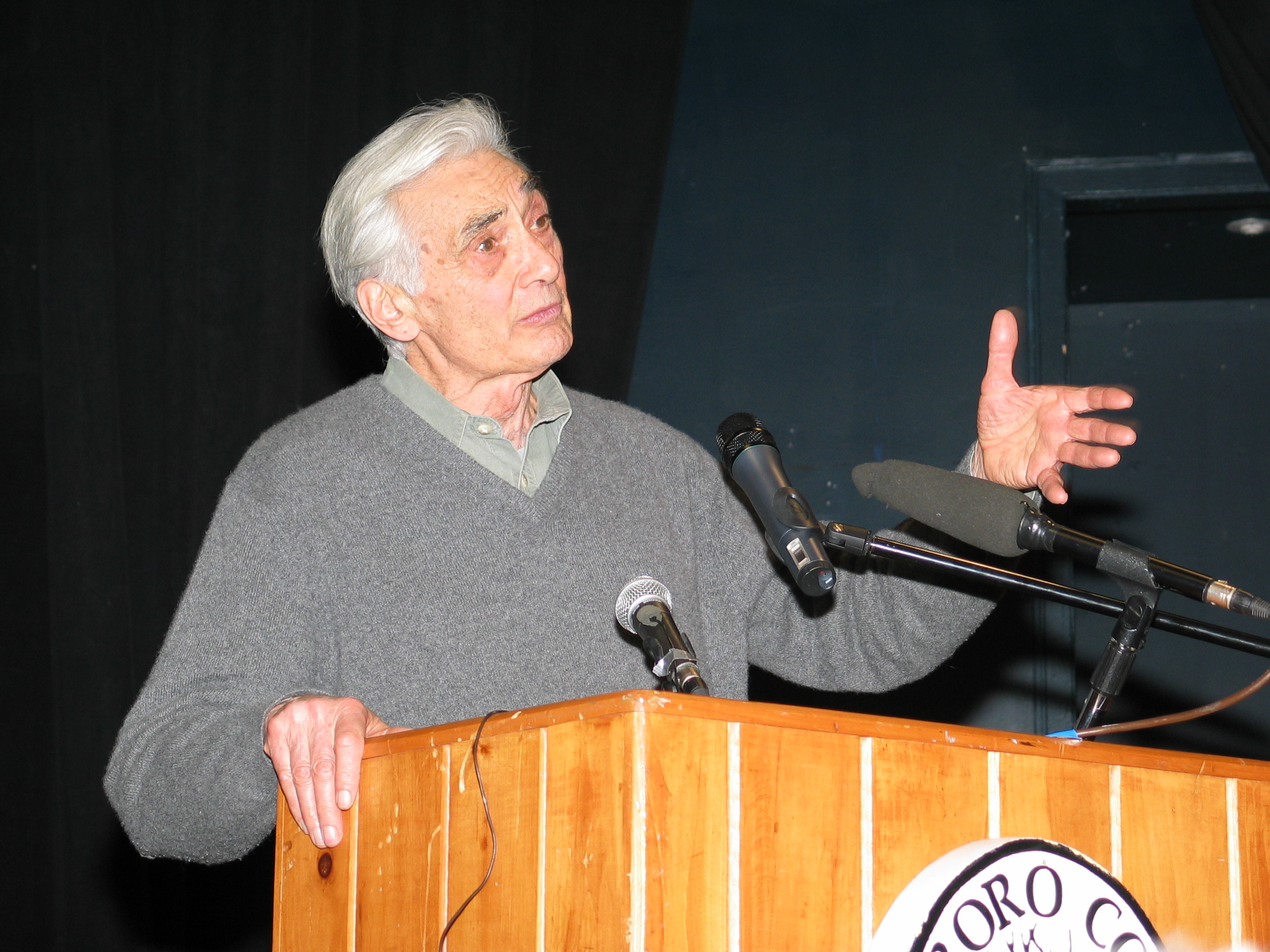

Howard Zinn

Howard Zinn was a progressive historian who called on archivists to take an active role in providing voices to the disenfranchised and to advocate for open records keeping policies.[55]

Contributions to Ethical Thought

Howard Zinn addressed archivists in the 1970s, stating that he believed that it was time for archivists to stop hiding behind the professional neutrality. Zinn believed that there was a tendency for professionals to attempt to separate their professional duties, responsibilities, and activities from social issues.[56] Zinn referred to it as a powerful form of "social control" intended to keep professionals supporting the status quo whether or not the professionals intended to. Zinn stated that "by social control I mean maintaining things as they are, preserving traditional arrangements, preventing any sharp change in how the society distributes wealth and power." [57] This social control is necessary, according to Zinn, because the skills and knowledge of professionals would present a serious challenge to the status quo were it not contained by professionalism. The role of archivists in this is even greater because of the special role that archivists play in the maintenance of power structures of society at the same level as military scientists: conducting work that gives tools to the powerful. [58] According to Zinn, this is based on the assumption that professions are not inherently political and neutral. [59] Despite the insistence of archivists that they neutrally work at preserving records, Zinn states that they inherently “maintain the existing social order by perpetuating its values, by legitimizing its priorities, by justifying its wars, perpetuating its prejudices, contributing to its xenophobia, and apologizing for its class order.” [60] He goes on to say that this is an acknowledged phenomenon in other places, but that archivists seem to believe that they are immune to it. Despite their insistence on the inherently neutral nature of their jobs, Zinn argues that is in fact the opposite: the ordinary course of the archivist’s job is in fact inherently promoting the status quo. He states that to recognize and confront this is not to politicize an inherently neutral profession but to humanize “an inevitably political” profession.[61] Because of the inherent political nature of the archivist’s profession, Howard Zinn calls on archivists to do two things: advocate for the opening of all government documents and to work to compile the documentary heritage of ordinary people, rather than the most powerful and wealthy. [62] These proposals would later be seen in the ethical codes of archival associations.

Randall Jimerson

Randall Jimerson is a professor of history at Western Washington University and has written extensively on the role of archivists in obtaining social justice and the ethical responsibilities of the archival profession. [63] He is a former president of the Society of American Archivists and currently chairs the Committee on Ethics and Professional Conduct. [64]

Contributions to Ethical Thought

Randall Jimerson echoes many of the Howard Zinn’s beliefs about the inherent politicization of archives. Writing in 2007, Randall Jimerson believes that the lack of neutrality inherent in the archival profession had only recently begun to be addressed. [65] Archives, in Jimerson’s opinion, can be used by the powerful and wealthy to control society and maintain the status quo. From this, Jimerson argues that archivists have a moral obligation to balance the support that is given to the power elites in archives by providing equal voice to groups that have often been silenced. [66] Jimerson asserts that archives are a tool to redress the wrongs of the past and that archivists have a crucial role in achieving that. Jimerson asserts that that archives play a crucial role in promoting accountability, open government, social, justice, and diversity. [67]Jimerson believes that archivists have an obligation to commit themselves to promoting these principles to ensure that archives are benefiting everyone, not just the power elites. [68]

Verne Harris

Verne Harris is a South African archivist who has written extensively on the use of archives are places of power. Writing from the perspective of a man who witnessed the down fall of apartheid in South Africa, Verne Harris emphasizes the ways in which archives have been used by power elites to maintain power and the moral and ethical requirements of archivists in the face of the inherent power of the act of preserving or destroying records. [69]

Contributions to Ethical Thought

Verene Harris identifies the archives of the South African apartheid state as a tool that was used deliberately. [70] Records acquisition and preservation were targeted at the records which promoted the narratives of the state and a systematic destruction of records which demonstrated the crimes of said state was undertaken. [71] This, combined with the systematic control of memory that was conducted throughout various cultural institutions in the apartheid regime allowed the South African government to attempt to legitimize its power and policies. [72] According to Harris, the national archives of South Africa were ill equipped to resist such a use of the historical record as weak powers and ineffective legislation provided them little opportunity to ensure that a full documentary picture was preserved. [73] Although the mandate of the State Archives Service of South Africa mandated that access to records was free of charge, systemic discrimination and poorly coordinated and executed outreach efforts ensured that majority of archives patrons were white. [74] Despite the lack of capacity to resist apartheid narratives, Harris also points out that it is important to acknowledge that in large part the archivists of South Africa were also unwilling to resist as the structure of the State Archives Service ensured that the leadership of the national archives were in line with the apartheid goal. [75] This complacency with the apartheid state was both systemic and purposeful, with collection policies being directed at white perspectives and white movements, and almost no records of a resistance to apartheid being acquired. [76] Harris uses this experience to argue that archives, as a glimpse into human experiences, can never be impartial and so neither can archivists. [77] Harris calls on archivists to accept this, and to use it to engage continually the idea of otherness “honestly, and openly, without blueprint, without solution, without answers.”

See Also

Archives and Power

Archives and Copyright

Archives and Repressive Regimes

References

- ↑ Cox, Richard J. "Archival Ethics: The Truth of the Matter." Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. no. 7 (2008): 1128-1133 pp. 1128

- ↑ Dingwall, Glenn. "Trusting Archivists: The Role of Archival Ethics Codes in Establishing Public Faith." The American Archivist. 67. no. 1 (2004): 11-30 pp. 12

- ↑ Merriam Webster, "ethic." Last modified 2013. Accessed April 12, 2013. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ethic.

- ↑ Dingwall, Glenn. "Trusting Archivists: The Role of Archival Ethics Codes in Establishing Public Faith." The American Archivist. 67. no. 1 (2004): 11-30 pp. 17

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid pp. 18

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid. 20

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Horn, pp.65

- ↑ Dingwall pp. 13

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid pp. 21

- ↑ Horn, pp.65

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid pp. 69

- ↑ Society of American Archivists, "SAA Core Values Statement and Code of Ethics." Last modified Janurary 2012. Accessed April 12, 2013. http://www2.archivists.org/statements/saa-core-values-statement-and-code-of-ethics.

- ↑ Association of Canadian Archivists, "Code of Ethics." Last modified 2013. Accessed April 12, 2013. http://archivists.ca/content/code-ethics.

- ↑ International Council on Archives, "Code of Ethics." Last modified September 6, 1996. Accessed April 12, 2013.

- ↑ Cox pp. 1130

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid pp. 1132

- ↑ NEAZOR, MARY. "Recordkeeping Professional Ethics and their Application." Archivaria. 64. (2007): 47–87 pp. 83

- ↑ Dingwall pp. 29

- ↑ Society of American Archivists

- ↑ Association of Canadian Archivists

- ↑ International Council on Archives

- ↑ Association of Canadian Archivists

- ↑ Society of American Archivists

- ↑ Association of Canadian Archivists

- ↑ International Council on Archives

- ↑ Society of American Archivists

- ↑ Jimerson , Randall C. "Archives for All: Professional Responsibility and Social Justice.” The American Archivist. 70. (2010): 252–281.

- ↑ Zinn , Howard. "SECRECY, ARCHIVES, AND THE PUBLIC INTEREST." THE MIDWESTERN ARCHIVIST. 2. no. 2 (1977): 14-26.

- ↑ Harris , Verne. "The Archival Sliver: Power, Memory, and Archives in South Africa." Archival Science. (2002): 63-83. pp. 63

- ↑ Jimerson pp. 254

- ↑ Jimerson

- ↑ Zinn

- ↑ Harris

- ↑ Jimerson pp. 281

- ↑ Zinn pp. 25

- ↑ Harris pp. 86

- ↑ Zinn, Howard. "SECRECY, ARCHIVES, AND THE PUBLIC INTEREST." THE MIDWESTERN ARCHIVIST. 2. no. 2 (1977): 14-26.

- ↑ Ibid. pp 15

- ↑ Ibid. pp. 16

- ↑ Ibid. pp 17

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid pp. 18

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid pp. 25

- ↑ Society of American Archivists, "Randall C. Jimerson." Last modified 2013. Accessed April 12, 2013. http://www2.archivists.org/history/leaders/randall-c-jimerson.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Jimerson, Randall C. "Archives for All: Professional Responsibility and Social Justice.” The American Archivist. 70. (2010): 252–281.

- ↑ Ibid pp. 254

- ↑ Ibid pp. 256-269

- ↑ Ibid pp. 281

- ↑ Harris, Verne. "The Archival Sliver: Power, Memory, and Archives in South Africa." Archival Science. (2002): 63-83. pp. 63

- ↑ Ibid pp. 71

- ↑ Ibid pp. 69

- ↑ Ibid pp. 70

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid pp. 71

- ↑ Ibid pp. 72

- ↑ Ibid pp. 74

- ↑ Ibid pp. 85