Course:ANTH213/2024/topic/Representation2

Introduction

Representation is "the act of presenting somebody/something in a particular way; something that shows or describes something"[1]. Representation has the ability to influence the way people perceive and think about other people and cultures, especially depending on how they are represented and how often they are represented in such a manner. When certain groups are presented consistently in negative ways for an extended period of time, this can lead to othering, which is when individuals and groups are treated differently and seen as inferior and dangerous to the dominant social group[2]. The representation of marginalized communities occurs when their narratives are taken out of context to serve the political and psychological needs of the authoritative group. Strategies in culture, media and public discourse are tools of representation used in the process of othering. Examples of representation as othering can be seen in disempowered groups such as those who are neurodiverse, mentally ill, sex workers, are transgender and are subjected to colourism. It is important to acknowledge that representation as othering does not exclusively apply to these groups, but affects many different marginalized groups. Groups that don't subscribe to hegemonic masculine ideals of gender are often targets of misrepresentation and subjected to the consequences of othering.

Representation of Neurodiversity

Neurodiversity as argued by S. L Amrutha and Luke Gerald Christie is a concept and method of self-representation that frames cognitive differences present in diagnoses such as autism, ADHD, dyslexia and others as "...naturally occurring cognitive variations with distinctive strengths that have contributed to the evolution of technology and culture rather than mere checklists of deficits and dysfunctions."[3] This model rose in response to the neurotypical (meaning non-neurodivergent) majority's medicalization [or deficiency] model of the neurodivergent community that led to stigmatization of these diagnoses.[4] Under the neurotypical model, physicians equate what is normative with what is natural and good, which academics such as Suzanne J Kessler oppose arguing that "...the culture/nature distinction is itself a construction..." meaning that the framework of understanding the world that society has normalized is not the only valid and healthy way to experience the world.[2]

Neurotypical representations of neurodivergence often lead to neurodivergents being perceived as unrelatable to the neurotypical majority and not entirely cognizant.[5] For example, in the film Rain Man, Erin Heath argues that the autistic character, Raymond, is portrayed as deficient and unable to make moral choices, being reliant on his brother and possessing illogical quirks that appear strange and disruptive to the neurotypical audience such as how Raymond demands his bed must always be next to the window.[6] Heath argues that what the audience does not see is the explanation as to how this might sooth the Raymond as many autistics have logical reasons for the rituals which they perform.[6] While neurodiverse individuals do have unique struggles, the treatment of these issues is argued by Heath to be more suggesting that Raymond is deficient then legitimately attempting to understand the complexities of neurodiverse life.[5] This deficient representation is a form of medicalization, “...the process through which social phenomena come to be regulated by medical authorities”.[7] Many who are medicalized including neurodivergents feel harmed by this form of representation seeing their cognition as a valid way to experience the world.[2]

In some cases, medicalizing representations of the neurodiverse becomes more extreme and progress into criminalization or even the suggestion of eliminating said neurodivergence.[8][9] For example, despite neurodivergents being "...more likely to be the victims of crime than the perpetrators...", ADHD is often demonized and tied with criminality especially for men.[8] This imagined risk leads to the neurotypical majority fearing ADHD and can be used as justification to pressure mothers into the "...monitor[ing] and control[ing] [of their pregnant]... bodies [by the medical establishment]..." to prevent actions which are theorized to lead to a child with ADHD.[10] In Rayna Rapp's similarly themed ethnography looking at Down's Syndrome and reproduction, Rapp argues that society holds a similar perspective towards this neurodivergence that while not associated with criminality, is depicted as something to be possibly eliminated via early detection with prenatal screenings.[9] This again serves as justification for the monitoring and control of pregnant bodies to detect what the medical establishment sees as "...wrong babies...".[11] Both of these examples could be considered forms of stratified reproduction where some births are valued more highly than others with neurodivergent births being actively discouraged.[12]

Another form of neurodivergent misrepresentation is to reduce neurodiversity into a personality trait. Angela J. Kim argues that this is seen on websites such as Buzzfeed that will write articles with titles such as "...'These Pictures will Trigger the Hell out of Your OCD'... [thereby giving] the impression that the disability is up for grabs while undermining its severity and pushing a metanarrative of frivolity."[13] Kim further argues that OCD can be depicted as a good disability as it carries the narrative that it "...forces one to be organized, clean, and productive...".[13] Representations such as these are argued by Kim to be easily comprehendible to the neurotypical majority, but harmful and undermining of the serious difficulties that those with OCD face.[13]

The last common form of misrepresentation in the neurodivergent community is tokenism, or the insertion of marginalized character for the appearance of representation without developing said token character into a full individual beyond their source of marginalization.[14] An example of this is found during interviews undertaken by Gareth M. Thomas, where many parents of children with Down's Syndrome were dissatisfied with the portrayal of characters with this neurodivergence in the British soap opera Coronation Street, finding that the character's personalities were limited to their disability and that they did not appear as "...multidimensional, active citizens with their own experiences and life stories...".[15] Interviewees stated that they wished depictions of Down's Syndrome were more "...mundane..." in that they could lead to a "...normalizing rather than sensationalizing [effect]...".[15] A good example of this preferred form of representation is seen in Kai-Ti Tao and Denise Wood's research into Activision-Blizzard's video game Overwatch where the autistic character Symmetra's neurodivergence is "... not [presented as] something that either lends her a special advantage or... [as a] limitation she has to compensate for.".[16] Autistic gamers observing Symmetra were happy that the character's presence prompted "...conversation about difference, diversity, and inclusion..." and were particularly pleased by Activision-Blizzard's choice to make Symmetra a woman and person of color, understanding that these groups are less seen in the mainstream autistic community as a result of being "...underrepresented in research studies...".[17]

Despite the difficulties society has had in the past representing uniquely neurodivergent struggles in a respectful manner that is not pathologizing or sensationalizing, there are various examples of positive representation that go beyond being inclusive. Among others, Heath argues that Mary and Max excels in depicting its autistic protagonist Max where the film Rain Man fails, by giving Max agency and voice that is denied to Raymond and makes Max cognizant and capable of moral choices thereby making him a much stronger character.[18] For example, Max's quirk of being triggered by the visual stimuli of cigarette butts and litter is not immediately understandable to a neurotypical viewer, but rather than be depicted as illogical or sick, the audience is given an explanation using Max's own voice.[19] Furthermore, despite being a non-verbal protagonist, Max is humanized and depicted as strongly cognizant by having his rich inner world showcased to the viewer via his read aloud written letters that are sent to Mary thus allowing the audience to hear his voice.[20] Unlike Raymond who is depicted as incapable of personal growth, Max grows throughout the movie and learns from his conflict with Mary after she commits an act all too familiar to autistic individuals, treating Max as if his condition is something to be cured rather than a mode of cognition that he identifies with feeling pride and belonging in an autistic community.[21] Respectful representations such as that in Mary and Max validate neurodivergent individuals and better educate the neurotypical majority.[21]

As argued by Amrutha and Christie, authentic neurodivergent representation threatens the powerful majority as neurodivergents often "...act, think, write, and speak in a way that subverts and questions social norms...".[22] For example, the tendency of neurodivergents to question gender as a social construct threatens colonial ideas of patriarchy and society's conceptions of masculinity and femininity.[4] Using Barbara Harlow's ideas from the introduction of The Colonial Harem, it becomes visible how the neurodivergent experience is ripped away from its "...indigenous context only to [be reinscribed]... within a framework that answers to the political and psychological needs of [the neurotypical majority]...".[23]

Regardless of how neurodivergent individuals are represented or misrepresented, another common theme is that cisgender men are widely overrepresented in neurodivergent communities despite there not being evidence that the majority of neurodiverse minds are male. According to the Australian Psychological Society, women and nonbinary neurodivergents receive less diagnoses and therefore receive less relevant support to their needs.[24] The Australian Psychological Society further argues that the main cause for this is that groups that develop diagnoses guidelines developed them using a sample consisting of mostly cisgender men, therefore missing how neurodivergence can manifest differently across gender and leading to a lack of neurodiverse representation that is not straight white cisgender males.[24]

Representation of Mental Illness

The representation of mental illness in society, media, and social and legal institutions has a profound effect on those suffering from mental illness. Mental illnesses are clinically significant disturbances in thinking, behavior, and regulations of emotion[25], while othering is “a process whereby individuals and groups are treated and marked as different and inferior from the dominant social group”[2]. The dominant social group in this case are people who do not live with mental illness and mental health issues. Three ways in which this plays out are in medical, criminal and gendered discourses and spaces. Positive representations of mental illness can have a positive impact, helping to de-stigmatize mental illness and humanizing its subjects.

Gendered representations of mental illness have the effect of othering or marginalizing those who do not conform to it. Gender is a socially constructed phenomenon about the differences between men and women. The powerful legacy of sexist patriarchy has represented mental illness as more common and dangerous in the weaker, irrational, more emotional sex[26]Representations of mental illness as particularly feminine serve to Other and marginalize women, and indeed these discourses served to institutionalize, control and disempower women. All throughout history, women who didn’t follow societal expectations were labelled with the disorder of ‘hysteria’[26]. This has the ongoing impact that mental illness is represented as a feminine issue. This leads to men to be less likely to seek mental health support[27] and women to be further othered. Representation of women with mental illness in the media pushes this narrative that mental illness is often coded as feminine. Women suffering from mental illness are portrayed as insane[28] or as sad[29]. Research has also shown being gender nonconforming and not heterosexual, therefore not fitting into the expectation of heteronormativity have a significant negative impact on psychological well-being[30]. An example of this is seen in work by anthropologist Dai Kojima, who interviewed queer Asian migrants about their experience in Vancouver. One example was the narrative of a man with 'manic depression' which leads to him leaving school and relying on social support[31]. He does not identify as gay, but participates in knitting, which he feels makes him gay and makes him feel shame. Not conforming to society’s gender roles cause him to suffer more with his mental illness. The inherited sexism of a patriarchal society, means that the representations of gender and mental illness harm and other people.

Mental illness is also often represented as criminal, especially in the media. Rather than representing mental illness as holistically emerging from personal, societal, economic, political, and genetic factors, many representations produce mental illness as a disease or malignant deviancy and this further stigmatizes and marginalizes people in a community. Criminalization is the process in which a “phenomena historically controlled by medical authorities comes to be governed by the criminal law” [7]. This can be done in many ways such as during criminal trials, using sensationalized headlines which represent individuals as dangerous, jailing them for a longer than a typical offender, and framing mental illness as a moral, rather than medical problem. Mentally ill people are often criminalized and misrepresented. Often this misrepresentation stems from the media as scholar Norman Ghiasi notes: “The public perception of psychiatric patients as dangerous individuals is often rooted in the portrayal of criminals in the media as “crazy” individuals."[32] and “violent and criminal” [33]. This representation of mentally ill individuals is actively harmful to the community, because instead of being treated for mental illness, many mentally ill individuals are locked up, and incarceration becomes the government’s way of managing them. Studies have shown these representations of them as “violent and criminal” have long term effects and produce more stigma about them leading to real world consequences as ““People with mental illness are more likely to be a victim of violent crime than the perpetrator. This bias extends all the way to the criminal justice system, where persons with mental illness get treated as criminals, arrested, charged, and jailed for a longer time in jail compared to the general population”[32]. These representations of mentally ill people as violent and a public threat can also lead to their deaths, especially at the hands of police, where “1 in 4” fatal encounters with the police involve someone experiencing serious mental health issues[34]. The way the media portrays mental illness also has personal consequences, leading to people less likely to adhere to their medication schedules and to seek help when experiencing a crisis[35]. By criminalizing people with mental health issues, they are placed in harm's way at both an individual and structural level.

There is also an issue of people with mental illness being medicalized, “the process through which social phenomena come to be regulated by medical authorities”[7]. When characteristics of people that are part of the human condition are represented as ‘unnatural’ and pathologized, this can lead to change in the way they are treated and further stigmatize an already othered group. Homosexuality is an example of a natural human behaviour that was further stigmatized after it was added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), the diagnostic manual of mental illnesses primarily used in North America[36]. Mental illness is also viewed differently than physical illnesses, represented as being ‘all in one’s head’ which leads to mental illnesses not being taken as seriously as physical illness[37]. Many people suffering from mental illness “commonly report feeling devalued, dismissed, and dehumanized by many of the health professionals with whom they come into contact”[38]. This dehumanization and devaluation, especially from people that are supposed to help them further others mentally ill individuals. While mental illness is both a psychological and physical issue, over-medicalization of mental illness can lead to over-treatment, with many individuals prescribed medication they do not need, something that massive pharmaceutical companies want as it drives up their profits[39]. Over-treatment harms occur when “normal life experiences (such as menopause, shyness, grief, etc.) are deemed illnesses or when diseases are “created” from mild problems and symptoms”[39]. Over-treatment has many downsides, such as unnecessary treatment, increased stigma, and extra costs of tests and treatment. Mental illness needs to be recognized and treated, not over-medicalized and treated as a social problem which is a part of medicalization.

Although mental illness is represented poorly in many aspects of society, there is power that comes from positive portrayals - as research has shown. The use of media “may also be an important ally in challenging public prejudices, initiating public debate, and projecting positive, human interest stories about people who live with mental illness”[35].When othered groups of people are able to represent themselves and protest on their own terms, this allows them to reclaim some of their power and to take back the stigma associated with their otherness. This type of fighting back against a system that misrepresents them is an act of resistance[40]. This resistance can then lead to reduction of social stigma and even policy changes[40]. When people who are othered are able to represent themselves in their own way, they feel more empowered. By sharing stories, othered people hope that they can make a connection with others and this will lead to them getting the resources they need[41]. This type of knowledge creation, which includes community members, is incredibly important in letting people represent themselves on their own terms, especially in groups that have been harmed by past research practices by systems meant to exploit them[42]. By coming together and sharing the reality of their lives in their own authentic voices, othered people are taking their power back[40][42] [41].

Representation of Sex Work

Sex workers have long been placed in a controversial othered group fraught with assumptions of what working in the sex industry industry entails. By definition, sex work can be understood as the a commercial sexual service provided in exchange for material compensation typically as money[43]. How the public has come to understand sex work is though representation in the media, statistics/news on crime and violence, and public discourse. Defined by layers of stigma and stereotypes, the individual perspective of sex workers are not often considered thus their representation is at the hands of policymakers, academics, doctors, and those with greater social capital. Sex workers are a group to be talked about rather than talked with; they are objectified not just in terms of body and sex but also moral objects that need to be regulated, saved, and protected. Like many othered groups, sex workers are “publicly visible but unseen” and are seldom heard on their own terms [44]. This section will examine how representation is used as a tool in the marginalization of sex workers and the sites of knowledge production involved in the creation of their narrative.

In terms of this section, those who are considered as “non- sex workers” are individuals or groups who have neither worked in the sex industry nor interacted with those who have/do in a way that has truly taken their story into account. This consists of many policy makers, social organizations, the medical field, academics, and the general public who have determined the needs of sex workers to serve political and social agendas.

The othering of sex workers begins with public discourse; whatever term is used– prostitute, sex worker, victim of sex trafficking– comes with a certain connotation. To focus on the word as an identification of an act serves as a way to identify and categorize certain individuals in a specific way that can play a role in reproducing stigma. [45] Whatever term is used and the choice of words surrounding sex work can be understood as a reflection of the speakers view point. Often referred to as prostitutes, Carol Leigh coined the term “sex work” to create a more tolerant atmosphere within the “women’s movement for working in the sex industry” and the broader public[43]. This term shifts emphasis from a moral understanding to a more economic description of the engagement of exchanging sex for material compensation [45]. However others, like radical feminist Sheila Jefferys, prefer the term “prostituted woman” or “survivor” to symbolize the lack of choice women have in their role in sex industry.[43]

Historical representations have contributed to the stereotyping and stigmatization of sex workers. These early views have influenced societal attitudes of sex work which has shaped political and social responses towards sex workers and their needs. In the early 1800s “prostitution” was seen as a moral, social, sanitary, and threat to the public and symbolized disorder and immoral pleasure.” [45]The church deemed sex workers “Fallen women” who needed to be saved by religion. This led to the development of the social reform narrative that places blame on the individual and suggests that some form of rehabilitation is in order. Social work reformers tended to employ an individualized treatment approach labelling women involved in the sex industry as “Wayward girls”, a cultural symbol of female deviance, who needed to repair themselves[45].This ties in with more medical narratives that ties sex work with social problems like sexually transmitted diseases. Criminalization of sickness is used a method of social control of disease that employ layers of stigma, fear, and labels to place blame on "the other"[7]. Similarly to criminalization of AIDS/HIV that targeted gay men, sex workers are of used as a scapegoat for spread of infections which allows for the moral agenda of reform to imposed upon them. [45]

These representations of the needs of sex workers often have underlying aims: of protecting women’s sexuality, control illegal immigration, and mitigate criminal activities. When regulating sex work, policy makers often equate it to human trafficking or sexual slavery[45]. This narrative is a product from the early twentieth century when sex work was perceived as “white slavery” [45]. With increases in immigration, women were seen as naive victims being trafficked against their will at the hand of newcomers and thus they needed to be protected [45]. This can be seen as being related to early twentieth century efforts to make Canada a white settler nation in the racial anxiety that dedicated their decisions on immigration policies [46]. In an effort to maintain “white purity”, restrictions were placed on white womens’ sexuality as they could not be “trusted to regulate themselves” from engaging in sexual activity with immigrant men[46]. Furthermore, the inclusion of immigrant women was seen as a solution to mixed race reproduction and as a way to protect white women against the immigrant man. The anti-trafficking approach towards sex work is a continuation of this governance of the female body and sexuality.

These public discussion on the ethics of sex work significantly lacked input and first hand accounts of the “everyday practice” and “ labour and workplace relation” of sex workers themselves .[47] However sex workers have found ways to have their voice heard.

In the 1970s, sex workers began coming together in social movements and organizations in effort to speak for themselves and to claim their rights [45]. This gave rise to several narratives from within the community of sex work. Some organizations believed that sex work should be recognized and respected as form of work and denying one to choose to work in the sex industry is a violation of women’s civil rights [45] COYOTE (Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics) was the first American sex workers rights organization and fought for the rights of sex workers and for sex work to be recognized as an “occupational choice” not a form of trafficking [45]. While other organizations like WHISPER (Women Hurt in Systems of Prostitution Engaged in Revolt) work in the sex work-as -violence framework and provide a space for women to share their stories working in the sex industry and receive support the harm they have experienced [45].While there are different perspectives of sex work, the foundational goal is to provide spaces for sex workers to share their stories and to take political action; rights based organizations continue to emerge fighting to improve the working conditions and safety for sex workers all while trying to eliminate discrimination. [45]

Given the lack of voice and control sex works have over their representation and the repercussions that follow, “Objects of desire collective” was established with the aim of sharing their narratives of sex workers. Concerned with the form, content, and lack of understanding in public discourses surrounding sex work, the group of artists anthropologists, and sex workers compiled a collection of objects that had been given to or used by sex workers[47]. By creating these object biographies, they were able to represent the narratives and labour relations of sex work. Thus the curation and presentation of these objects develops openness, promotes questions and examines sites of knowledge production in the discourse surrounding sex work. [47]The collective is focus on the discussion of labour rights and conditions that ensures the understanding of sex work as work. By challenging the objectification of sex workers as a group that needs to be managed, this exhibition channeled a discussion of labour rights and conditions that ensures the understanding of sex work as work.

A valuable tool in creating representation is through creative expression. Sex workers can not only tell their story but are able to shift the narrative of being “passive victims and social deviants” to “empowered artists, activists, and scholars” [45]. Through modes of art, they are able to express their unique experiences and identities emphasizing the variety of voices of pain, power, and hard work . This form of expression can provide sex workers with the opportunity to shape their representation by reaching broader audiences like academics, social organizations, and the general public.

Arts based research provides a space for sex workers to be involved in the creation of their own representation [45] This creative expression and representation of research data can provide a more in depth understanding of the needs and aspirations of sex workers. One project that exhibits this is the photovoice methods implemented in study by Capous Desyllas in which eleven female sex workers of diverse backgrounds working in a variety of aspects of sex work were provided cameras to document their lives to better. The photographs provided “symbolic, emotional, and aesthetic responses” to Desyllas' questions about their needs and aspirations in addition to demonstrating how participants’ “multiple identities and social locations “shaped their unique experiences. Much like conducting interviews in In plain sight, the aims of this study were to give space for women who are not often “heard on their own terms”. However these more traditional methods of qualitative research have limitations in the ways participants are able to shape the stories themselves [45]. Arts based research has the power to give a voice to those who are often silenced by connecting research with lived experience and “making meaning through multiple senses and media”.

Trans Representation

Trans is an umbrella term used to describe both transgender and transsexual people as well as other gender identities including gender-fluid, agender, etc,[48]. Often, transgender people are someone who does not identify the same as their assigned gender at birth. Meaning if someone who was assigned female at birth has a masculine self identification, they could identify themselves as transgender. On the other hand, transsexual are used for people who had medical treatment to be closer to their gender identity, often through hormones or surgeries. However, this division of pre-surgery and post-surgery are not a universal experience to all transgender/transsexual people, and the use of transsexual could be assaulting for trans people[49]. Therefore, the umbrella term “Trans” is used not to be offensive or stigmatize anyone. Something to be careful here is that transgender/ transsexual is a gender identity, and it is a different thing from their sexuality.

Trans representation is most remarkable in film and media. The beginning of representation here refers to when trans people began to be recognized as “trans”. In other words, before the word "trans" or other discriminatory terminology were used, trans people were not recognized as "trans" but as someone who does not fit in the gender binary and is weird.

In the Netflix documentary Disclosure it was mentioned that Judith of Bethulia, the 1914 film by D.W. Griffith can be one of the earliest films where a gender non-conforming appeared[50]. Because the gender norm is shaped by pink or blue, polarized male or female tropes everywhere and it is worn, visualized and chosen before even you are born, trans representation was erased and forced to put into either one gender binary[51].

However, even trans representation started to be seen in mainstream media, it was often seen as a Transjoke[52]. Trans actors were on stage often cross-dressed or mimicking the female body as a form of comedy. Trans representation has been used not for trans people to find themselves in it but for cisgender people to make fun of. In other words, trans people were introduced in the mainstream media as “others” that do not fit into the cisgender society, including them in the media representation but excluding them from the cisheteronormative society at the same time.

Although trans representation has increased, the more they are exposed, the more they are violated[53]. Visibility of trans people did not necessarily lead to empowering the community but instead, it puts them in more danger. This is widespread quickly since as the GLAAD research shows, 80% of Americans do not actually know any trans person personally[54]. However this representation of trans people as a “joke” also affected trans people themselves. Most trans people themselves also do not grow up in an environment where trans people are around, so the only reference both cisgender and trans people have is what they see on medial[55]. It was quite clear that trans people were alienated and seen as extreme “others” of the society.

Trans masculinity is a term used for those assigned female at birth and whose gender identity or expression (or both) is masculine but not necessarily male[56]. Although trans male and female ratio are almost the same just like cisgendered people, there are more trans women and women in general because they are seen as commodifiable assets[57]. Trans masculine representation was not well shown in the media at this time and even today. One example of trans masculine representation is the Original Plumbing magazines where lifestyles of trans men were shared but often in a hyper-sexualized way[58].

Although trans men identify themselves as men, it still does not fully fit the societal acceptance of masculinity which leads to the idea of trans masculinity as a form of othering from cisgender male society.

In addition, trans black men face more of this “othering” from their racial identity. Unlike white trans men being shown as elegant and polite in films, black trans men were portrayed as hyper-masculine, violent, and aggressive characters also seen as a predator to white womanhood. Often, these black trans characters were performed by white actors doing blackface. This same “protecting our women” rhetoric is used throughout history[59].

In 1887, the Canadian federal government implemented the Act to Restrict Chinese Immigration. They saw the increase of Asian immigrants in Canada as a threat to Whiteness. At first they banned Asian women from entering the country to prevent them having “uncontrollable reproduction”. However, soon later they lifted the ban and accepted Asian women entering the country as a method for Asian men to stick with Asian women, and protecting white women from the threat of violence by Asian men. Although their race is different, the rhetoric of protecting white women from people of color can be seen here. Race works as othering trans black men from whiteness[60].

Trans femininity is a term used for those assigned male at birth and whose gender identity or expression (or both) is feminine but not necessarily female[56]. Once a trans person identifies as a woman, they face societal expectations of beauty and assumption of work.

Recently, trans celebrities like Laverne Cox and Caitlyn Jenner have been famous, popular, and become an icon of what it is to be trans[61]. In other words, the aesthetic of trans femininity is shaped by these well-known trans people, where a curved body feature with big breasts, blond long hair, and beautiful dress and makeup are what it is to be a trans woman. These beauty standards create an idea of “passing” where people start to see if trans individuals look trans enough or not. People who do not fit in these trans feminine looks are seen as excluded and not seen “real enough” to be a trans woman[62]. Here, cisgender audiences are holding the power to decide who is trans women and who are not, and othering occurs.

In addition, trans feminine people faces stereotype of their work as sex workers. Since trans woman faces occupational discrimination, many of trans women are forced to be in sex work industry. After media brought up the topic of trans femininity leading to sex work, trans women faced oppression from feminists. They argue that trans women are appropriating the female body and sex worker’s hyper-feminize their body as reinforcing patriarchy, harmful for womanhood, and degrading women[63]. Although they identify themselves as trans women, feminists exclude trans women from their womanhood seeing them as “other” aliens that threaten their rights and body.

Representations of trans people were not clearly visible or misinformed and disinformed throughout history, but trans people are not well represented in the LGBTQ+ community too. Trans people are othered from cisgender people and even within the queer community where they are supposed to belong to.

For instance, STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries) which was started by trans activists Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, the beginning of what we call "Pride" even today, were excluded by the gay rights movements. The National Women’s History Museum explains that the first pride parades started in 1970, but Rivera and other trans people were discriminated against, discouraged to participate, and not allowed to speak[64][65].

In addition, even when studies and research are done on queer communities, trans people are not represented at all. Kojima[66] conducted research on queer Asians in Vancouver as immigrants but all of the research subjects were cisgender gay men and no trans person. “Queer” seems to be an inclusive term and it is, but when it comes to how it is represented in academic fields, trans people are invisible.

Trans people are underrepresented in the LGBTQ+ community and often seen as “others” of the “majority gay and lesbian population”.

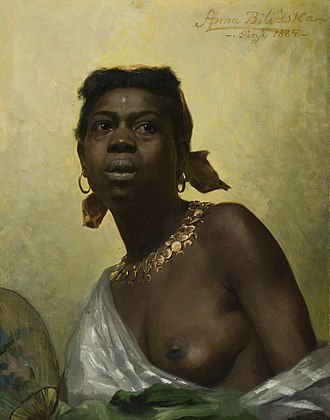

Colourism of Black Women in Representation

Colourism is a byproduct and sub-group of racism that utilizes social hierarchy as a result of colonialism to ascribe importance to a person depending on the lightness or darkness of their skin tone. The structure of colourism acts as “an extension of cultural stratification and is based on a system that consists of a dominant light-skinned Western and dominated dark-skinned non-Western populous”[67]. In order to uphold a sense of power over newly freed Black American people in the 19th century a new level of significance and authority was given to those with a lighter skin tone and the physical characteristics that were frequently associated with Eurocentric beauty standards. The Attractiveness and desirability of features such as straighter hair, narrower noses, and slender body types were given greater value and considered to be superior to darker skin tones, broader noses, and thicker body types, efficiently and effectively creating another way in which black people, black women especially, were purposefully discriminated against[68]. This in turn placed a great level of importance on those who possessed a proximity to whiteness, particularly because “according to the vestiges of colourism, [dark-skinned] people of colour were obviously not fit for civilization because they lacked the innate capacities of culture inherent in the capacities of colonial operatives”[69].

Due to this belief and their proximity to whiteness biracial and light-skinned Black Americans were considered to have certain advantages and attributes over their dark-skinned counterparts. Characteristics like intelligence, attractiveness, and overall appeal were ascribed to their skin tone which then provided them with more occupational advantages[70]. These advantages had great effects on how black women in particular were treated and contributed to the production of what is now a long history of biracial and light-skinned Black women being given jobs and opportunities that could have and should have been given to dark-skinned Black women, particularly in the film industry.

Western ideals of femininity along with the production of exclusionary Eurocentric beauty standards played very large roles in the ostracization of dark-skin women from portraying their own stories and histories. Completely rooted in European standards and notions of gender roles, “emphasized femininity is ‘the pattern of femininity which is given most cultural and ideological support… patterns such as sociability… compliance… and sexual receptivity to men”[71]. All of these are traits that are to this day never linked with Black women who are at large considered to be loud, over-opinionated, and hyper-masculine. Emphasized femininity is very often considered to be a reaction to hegemonic masculinity which “is the form of masculinity that is most highly valued in society and is rooted in the social dominance of men over women and non-hegemonic men (particularly homosexual [and black] men)”.[71]

In the film industry and especially in Hollywood, femininity is a vital product on account of the fact that it sells well and because of this fact the people who will be chosen to take part are those who can subscribe to the expected portrayals of how gender is supposed to look. These Eurocentric concepts of how gender is supposed to be performed are based on the perceptions of what is it to be human, a category that is almost exclusively ascribed to the hegemonic male, the “Eurocentric, Judeo-Christian, bourgeois male”[72], a category that distinctly excludes Black women in every facet of its meaning. Rooted in whiteness, accepted displays of femininity fall in line with proximity to whiteness, which is mixed and light-skin Black women, as they are considered to possess at least some traits of a ‘civilized person’ by default due to the tone of their skin.

Going hand in hand with lacking the title of ‘human,’ for much of North American history Black women were not considered to be women at all. What is considered to be markers of gender, psychological and behavioural traits that are designated as ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine[73],’ often do not coincide with stereotypical behaviours that are often associated with Black women, therefore putting their position as women into question. When such fields of thought about gender as psychological and behavioural are applied by experts in multiple fields, including medicine, psychology, the social sciences, and the humanities[73], a list of certain criteria is formed. In film, when looking for people to fill roles representing feminine characters the people that suit the supposed criteria of performing the gender of a woman are the natural choice. “Gender is used to point to social factors (social roles, position, behaviour)”[74] and this adherence to a biased standard works to automatically eliminate dark-skinned Black women, those who do not fit the made-up criteria of a feminine woman, from even being in the running for consideration, firmly placing them in a disadvantaged position in the industry.

There are many Black women that have features that do not suit the Eurocentric ideal of feminine beauty, and there are also a lot of Black women who do. Regardless of this fact, all dark-skinned Black women are placed in the same category of an ‘other’ type of woman rooted in racism as these beauty standards and gender ideals are designed to purposefully leave them out. This leaves very limited spaces for Black women in film, having the majority of available roles showcase unfounded and sometimes harmful stereotypical characters such as the ‘loud best friend’ or the ‘angry Black woman.’ Many other depictions focus on the promiscuity of the character and there are many films throughout Hollywood history that limit characters of women of colour to their desirability and ability to attract men[75]. This shows that for such characters to have strength or power, they must be attractive enough to hold power over a man’s desire, but to do so they must fit the criteria of the beauty standards.

Films telling stories that are based on real-life dark-skinned historical figures like The Harder They Fall[76] or films that are based on books featuring a dark-skinned main character like The Hate U Give[77] are just a couple of examples of roles in films that should exclusively be given to dark-skinned Black women but are often not. Hollywood has a long history of using white models to portray roles that are meant for people of colour as white women with a hint of exoticism were what was appealing to audiences. In hiring biracial and light-skinned actresses in place of dark-skinned actresses, like Zazie Beets (The Harder They Fall) or Amandla Stenberg (The Hate U Give), films are able to skirt the line of ‘representation’ while still being able to uphold it’s Eurocentric beauty standards.

Film is an effective tool that can used to influence the general population into believing and subscribing to a certain way of thinking and viewing other peoples and cultures and “by lumping various cultures together, American cinema fabricate[s] a collective portrayal… undifferentiated by cultural plurality”[75]. In using one type of person to portray an entire people, a “single story”[78] (cite) is formed, a linear narrative that does not properly represent the experiences of the people being depicted. This completely overtakes true stories and experiences of the people being portrayed and this new image becomes the narrative that is repeated and believed to be true by the audience. In using mostly lightskin actors to portray dark-skinned characters, the risk of telling a single story presents itself as the histories and stories become altered and taken over by inaccurate representations that do not embody the experiences and images of many black women.

References

List of the references here.

- ↑ "Representation". Oxford Learner's Dictionary.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Kessler, Suzanne J (Autumn 1990). "The Medical Construction of Gender: Case Management of Intersexed Infants". Signs. 16: 24–25 – via JSTOR. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name ":23" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Amrutha, S. L.; Christie, Luke Gerald (28 November 2023). "Neuroqueering Sexuality: Learning From The Life-Writings of Queer Neurodivergent Women". Sociology Compass. 18: 1 – via Wiley.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Amrutha, S. L.; Christie, Luke Gerald (28 November 2023). "Neuroqueering Sexuality: Learning From The Life-Writings of Queer Neurodivergent Women". Sociology Compass. 18: 2 – via Wiley.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Heath, Erin (2019). Mental Disorders in Popular Film : How Hollywood Uses, Shames, and Obscures Mental Diversity. Lanham Maryland: Lexington Books. p. 42. ISBN 9781498521710.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Heath, Erin (2019). Mental Disorders in Popular Film: How Hollywood Uses, Shames, and Obscures Mental Diversity. Lanham Maryland: Lexington Books. p. 42, 51. ISBN 9781498521710.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Hoppe, Trevor (January 2014). "From sickness to badness: The criminalization of HIV in Michigan". Social Science and Medicine. 101: 139–147 – via Science Direct.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Horton-Salway, Mary; Davies, Alison (2018). Media Representations of ADHD. London UK: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 89. ISBN 978-3-319-76026-1.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Rapp, Rayna (23 December, 2009). "Extra chromosomes and blue tulips: medico-familial interpretations". In Margaret Lock, Allan Young and Alberto Cambrosio (eds.). Living and Working with the New Medical Technologies: Intersections of Inquiry. Cambridge University Press. pp. 185. ISBN 9780511621765.

- ↑ Horton-Salway, Mary; Davies, Alison (2018). Media Representations of ADHD. London UK: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 86, 88. ISBN 978-3-319-76026-1.

- ↑ Rapp, Rayna (23 December, 2009). "Extra chromosomes and blue tulips: medico-familial interpretations". In Margaret Lock, Allan Young and Alberto Cambrosio (eds.). Living and Working with the New Medical Technologies: Intersections of Inquiry. Cambridge University Press. pp. 185-186. ISBN 9780511621765.

- ↑ Andaya, Elise; Cromer, Risa; Paxson, Heather; Sufrin, Carolyn (03 October 2022). "After Roe: Introduction". Society For Cultural Anthropology. Archived from the original on 05 October 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2024. Check date values in:

|date=, |archive-date=(help) - ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Kim, Angela J (26 May, 2021). "The metanarrative of OCD Deconstructing positive stereotypes in media and popular nomenclature". In David Bolt (eds.). Metanarratives of Disability Culture, Assumed Authority, and the Normative Social Order. Routledge. pp. 62. ISBN 9781003057437.

- ↑ Thomas, Gareth M (28 December 2020). ""The Media Love the Artificial Versions of What's Going On": Media (Mis)representations of Down's Syndrome". The British Journal of Sociology. 72: 699 – via Wiley.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Thomas, Gareth M (28 December 2020). ""The Media Love the Artificial Versions of What's Going On": Media (Mis)representations of Down's Syndrome". The British Journal of Sociology. 72: 699-700 – via Wiley.

- ↑ Kao, Kai-Ti and Denise Woods (29 December, 2022). "Outliers as Heroes: Disability, Representation, and Inclusion in Blizzard's Overwatch". In Katie Ellis, Tama Leaver and Mike Kent (eds.). Gaming Disability: Disability Perspectives on Contemporary Video Games. Routledge. pp. 44. ISBN 9780367357153.

- ↑ Kao, Kai-Ti and Denise Woods (29 December, 2022). "Outliers as Heroes: Disability, Representation, and Inclusion in Blizzard's Overwatch". In Katie Ellis, Tama Leaver and Mike Kent (eds.). Gaming Disability: Disability Perspectives on Contemporary Video Games. Routledge. pp. 49. ISBN 9780367357153.

- ↑ Heath, Erin (2019). Mental Disorders in Popular Film: How Hollywood Uses, Shames, and Obscures Mental Diversity. Lanham Maryland: Lexington Books. p. 50. ISBN 9781498521710.

- ↑ Heath, Erin (2019). Mental Disorders in Popular Film: How Hollywood Uses, Shames, and Obscures Mental Diversity. Lanham Maryland: Lexington Books. p. 51. ISBN 9781498521710.

- ↑ Heath, Erin (2019). Mental Disorders in Popular Film: How Hollywood Uses, Shames, and Obscures Mental Diversity. Lanham Maryland: Lexington Books. p. 50-51. ISBN 9781498521710.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Heath, Erin (2019). Mental Disorders in Popular Film: How Hollywood Uses, Shames, and Obscures Mental Diversity. Lanham Maryland: Lexington Books. p. 52-53. ISBN 9781498521710.

- ↑ Amrutha, S. L.; Christie, Luke Gerald (28 November 2023). "Neuroqueering Sexuality: Learning From The Life-Writings of Queer Neurodivergent Women". Sociology Compass. 18: 1 – via Wiley.

- ↑ Harlow, Barbara (1986). "Introduction". In Alloula, Malek. The Colonial Harem. (Translated by Mryna Godzich and Wlad Godzich), University of Minnesota Press. pp. xx. ISBN 9780816682188.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Riches, Caroline; North, Angela (14 March 2024). "Why Are So Many Neurodivergent Women Misdiagnosed?". Australian Psychological Society. Archived from the original on 30 March 2024. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ↑ "Mental Disorders". World Health Organization. 8 June 2022.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Tasca, Cecilia; Rapetti, Mariangela; Carta, Mauro Giovanni; Fadda, Bianca (19 October 2012). "Women And Hysteria In The History Of Mental Health". Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health : CP & EMH. 8: 110–119 – via PubMed Central.

- ↑ Lee, Jaewoo; Trudel, Remi (8 January 2024). "Man up! The mental health-feminine stereotype and its effect on the adoption of mental health apps". Journal of Consumer Psychology – via UBC Library.

- ↑ Kretschmar, Kelly, Framing Femininity as Insanity: Representations of Mental Illness in Women in Post-Classical Hollywood. May 2007, 94 pp., references, 69 titles. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc3654/m2/1/high_res_d/thesis.pdf

- ↑ Thelandersson, Frederika (2023). "1". [21st Century Media and Female Mental Health]. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-3-031-16755-3. Check

|title-link=value (help) - ↑ Rieger, Gerulf; Savin-Williams, Ritch C. (25 February 2011). "Gender Nonconformity, Sexual Orientation, and Psychological Well-Being". Archives of Sexual Behaviour. 41: 611–621 – via Springer Link.

- ↑ Kojima, Dai (2014). "Migrant Intimacies- Mobilities-in-Difference and Basue Tactics in Queer Asian Diasporas". Anthropologica. 56: 33–44 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Ghiasi, Norman; Azhar, Yusra; Singh, Jasbir (2023). Psychiatric Illness and Criminality. StatPearls Publishing.

- ↑ Wahl, Otto F. (1995). "Chapter 4: Murder and Mayhem". Media Madness: Public Images of Mental Illness. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 0813522129.

- ↑ Fuller, Doris A. (2015). "Overlooked in the Undercounted: The Role of Mental Illness in Fatal Law Enforcement Encounters".

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Stuart, Heather (29 August 2012). "Media Portrayal of Mental Illness and its Treatments". CNS Drugs. 20: 99–106 – via Springer Link.

- ↑ Drescher, Jack (4 December 2015). "Out of DSM: Depathologizing Homosexuality". Behav Sci (Basel). 5(4): 565–575 – via PubMed Central.

- ↑ Miller, John J. (7 April 2023). "Yes, Its All in Your Head". Psychiatric Times. 40(4) – via Psychiatric Times.

- ↑ Knaak, Stephanie; Mantler, Ed; Szeto, Andrew (16 February 2017). "Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare". Healthc Manage Forum. 30(2): 111–116 – via PubMed Central.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "The Paradox of Mental Health: Over-Treatment and Under-Recognition". PLoS Med. 10(5). 28 May 2013 – via PubMed Central.

|first=missing|last=(help) - ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Hubbard, J. (Director). (2012). United in Anger : A History of ACT UP [Film]. Ford Foundation

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Robertson, Leslie; Culhane, Dana (2005). In Plain Sight: Reflections on Life in Downtown Eastside Vancouver. Vancouver: Talonbooks. pp. 78–101. ISBN 0-88922-513-3.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Laing, M. Conversations with Young Two-Spirit, Trans and Queer Indigenous People in Toronto [zine]. Toronto, Canada

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 McCracken, Jill (2007). "Listening to the language of sexworkers: An analysis of street sexworker representations and their effects on sexworkers and society". Proquest. Retrieved March 2024. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Robertson, Leslie; Culhane, Dara (2005). In Plain Sight: Reflections on Life in Downtown Eastside Vancouver. Vancouver: Talonbooks. pp. 7–19. ISBN 0-88922-513-3.

- ↑ 45.00 45.01 45.02 45.03 45.04 45.05 45.06 45.07 45.08 45.09 45.10 45.11 45.12 45.13 45.14 45.15 Coupas Desyalles, Moushoula (December 5, 2013). "Representations of sex workers' needs and aspirations: A case for arts-based research". Sexualities. 16: 772–787 – via sage.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Dua, Enakshi (July 24 2007). "Exclusion through Inclusion: Female Asian migration in the making of Canada as a white settler nation". Gender, Place, & Culture: 445–466. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Jeevendrampillai, David; Burton, Julia; Sanglante, Eva (2021). "Objects of desire: Sexwork and its objects". In Carroll, Timothy; Wolford, Antonio; walton, shireen (eds.). Lineages and Advancements in Material Culture Studies. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-003-08586-7.

- ↑ Steinmetz, K. (2018, April 3). The OED added the word “trans*.” here’s what it means. Time. https://time.com/5211799/what-does-trans-asterisk-star-mean-dictionary/

- ↑ Abrams, M. (2023, May 22). Is there a difference between being transgender and transsexual? Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/transgender/difference-between-transgender-and-transsexual#transsexual-defined

- ↑ Haynes, S. (2020, June 19). Disclosure director on Trans Representation Onscreen. Time. https://time.com/5855071/disclosure-netflix-transgender-representation/

- ↑ Fausto-Sterling, A. (2012). Pink and blue forever. sex/gender. Routledge, pp. 123-125. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203127971-14

- ↑ Feder, S. & Scholder, A. (Producers). (2020, June 19). Disclosure [Documentary]. (6:34) https://www.netflix.com/ca-ja/title/81284247

- ↑ Feder, S. & Scholder, A. (Producers). (2020, June 19). Disclosure [Documentary]. (1:37) https://www.netflix.com/ca-ja/title/81284247

- ↑ Transgender media. GLAAD. (2024, January 26). https://glaad.org/transgender/

- ↑ Feder, S. & Scholder, A. (Producers). (2020, June 19). Disclosure [Documentary]. (21:23) https://www.netflix.com/ca-ja/title/81284247

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Gillespie, C. (2023, October 17). Transmasculine: What does having this identity mean?. Health. https://www.health.com/mind-body/transmasculine

- ↑ Feder, S. & Scholder, A. (Producers). (2020, June 19). Disclosure [Documentary]. (33:14). https://www.netflix.com/ca-ja/title/81284247

- ↑ Original Plumbing. Internet Archive . (n.d.). https://archive.org/search?query=creator%3A%22Original+Plumbing%22

- ↑ Feder, S. & Scholder, A. (Producers). (2020, June 19). Disclosure [Documentary]. (13:14). https://www.netflix.com/ca-ja/title/81284247

- ↑ Dua, E. (2007). Exclusion through Inclusion: Female Asian migration in the making of Canada as a white settler nation. Gender, Place & Culture, 14(4), 445–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/09663690701439751

- ↑ Staff, T. (2014, May 29). 25 transgender people who influenced American culture. Time. https://time.com/130734/transgender-celebrities-actors-athletes-in-america/

- ↑ Faye, S. (2015, October 20). To be real: On Trans Aesthetics and Authenticity. Verso. https://www.versobooks.com/en-ca/blogs/news/2293-to-be-real-on-trans-aesthetics-and-authenticity

- ↑ Feder, S. & Scholder, A. (Producers). (2020, June 19). Disclosure [Documentary]. https://www.netflix.com/ca-ja/title/81284247

- ↑ Rothberg, E. (2022). Sylvia Rivera. National Women’s History Museum. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/sylvia-rivera

- ↑ YouTube. (2019, August 8). Sylvia Rivera, “Y’all better quiet down” original authorized video, 1973 Gay Pride Rally NYC. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mprUOGBWCvY

- ↑ Kojima, D. (2014). Migrant intimacies: Mobilities-in-difference and basue tactics in queer asian adiasporas : Queer anthropology. Anthropologica (Ottawa), 56(1), pp. 33-44.

- ↑ Hall, Ronald E. (2022). Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Colorism: Beyond Black and White (1st ed.). New York: Routledge. p. 20. ISBN 9781000622256.

- ↑ Rosario, R. Josiah; Minor, Imani; Rogers, Leoandra Onnie (14 July 2021). ""Oh, You're Pretty for a Dark-Skinned Girl": Black Adolescent Girls' Identities and Resistance to Colorism". Journal of Adolescent Research. 36 (5): 502 – via Sage Journals.

- ↑ Hall, Ronald, E. (2022). Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Colorism: Beyond Black and White (1st ed.). New York: Routledge. p. 19. ISBN 9781000622256.

- ↑ Hall, Ronald, E. (2022). Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Colorism: Beyond Black and White (1st ed.). New York: Routledge. p. 75. ISBN 9781000622256.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Currier, Danielle M. (16 July 2013). "Strategic Ambiguity: Protecting Emphasized Femininity and Hegemonic Masculinity in the Hookup Culture". Gender & Society. 27 (5): 706 – via Sage Journals.

- ↑ Wade, Ashleigh Greene (1 August 2017). ""New Genres of Being Human": World Making through Viral Blackness". The Black Scholar. 47 (3: Black Code): 34 – via Taylor & Francis Online. line feed character in

|title=at position 42 (help) - ↑ 73.0 73.1 Karkazis, Katrina; Jordan-Young, Rebecca; Davis, Georgiann; Camporesi, Silvia (13 June 2012). "Out of Bounds? A Critique of the New Policies on Hyperandrogenism in Elite Female Athletes". The American Journal of Bioethics. 12 (7): 5 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ↑ Karkazis, Katrina; Jordan-Young, Rebecca; Davis, Georgiann; Camporesi, Silvia (13 June 2012). "Out of Bounds? A Critique of the New Policies on Hyperandrogenism in Elite Female Athletes". The American Journal of Bioethics. 12 (7): 6 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Kamal-Eldin, Tania (Director). (1999). Hollywood Harems [Film]. Women Make Movies.

- ↑ Samuel, Jeymes (Director). (2021). The Harder They Fall [Film]. Overbrook Entertainment.

- ↑ Tillman, George Jr. (2018). The Hate U Give [Film]. 20th Century Fox.

- ↑ Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi. (2009, July). The Danger of a Single Story [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story