Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/Legally illegal in BC-Granted tenures on Customary lands without consent

'Legally illegal in BC: A Case study with the Maiyoo Keyoh Society'

Video Clip from APTN's "Closer to Home" episode with Maiyoo Keyoh Society

Closer to Home: Keyoh Families

Background

This page represents a personal lived experience as an Indigenous person. My name is Seraphine, and I am a student here at UBC. Some of this information provided here will be both from academic papers and personal experiences with our customary lands. This is a case study of our traditional lands within central BC in an area known locally as the Dakelh territory. The Maiyoo Keyoh is an exclusive family owned ancestral territory that has existed since time immemorial. The political journey of our family began in response to rapid deforestation of our traditional lands. As a result, our family have enacted considerable efforts through land use & occupancy studies, PhD partnership studies, Forest Management plans, and countless hours of engagement protocols with MOF and local Indian Act Band representatives. As a disclaimer, please do not take this information as a case that encapsulates the political consultation landscape of all BC or surrounding Dakelh groups. This is one setting that was determined by the Indian Act policy and historical events specific to this region.

Brief Summary

As history has shown, it is evident that Canada has been exclusionary to Indigenous engagement and decision making over natural resources [1][2];. Logging under the practice of clearcutting has long been contested by Indigenous and contributes to the ongoing erasure of Aboriginal heritage, then further disconnecting continuing use that encompasses the values associated with governance, management, oral histories, and solidarity to say the least. The Duty to consult, in theory, was designed to address these issues; however, as demonstrated through various scholars and case law, namely, Haida v. British Columbia [Minister of Forests] (2004) consultation lacks meaningful accommodation and engagement. Resulting in the infringement upon the rights of Indigenous people under Section 35(1) of the Constitution Act (1867). Specifically, this damages the connections and bonds between groups and has influenced the dismantling of customary lands and its pre-existing governance structures, such as the case of my family lands and cultural landscape.

Historically, the tenure forest system granted exclusive rights and access to third parties over the ancestral lands of Indigenous . In particular, they have posed as a “structural and systemic impediment to the recognition and protection of Aboriginal and treaty rights in forest management in Canada”[1]. Moreover, there needs to be recognition of traditional customary lands as a legitimate authority according to case law under Haida v British Columbia (2004) [3]

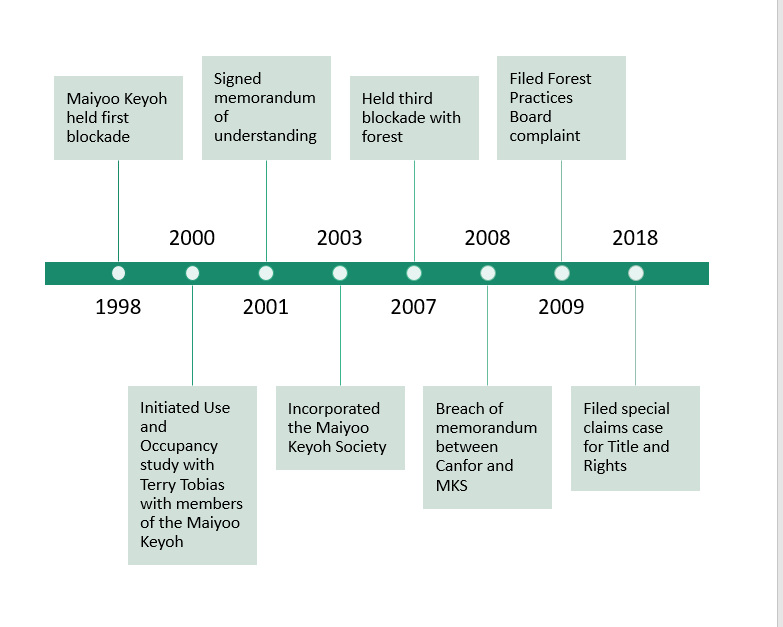

Timeline

Highlights concerning the Maiyoo Keyoh Society

Historical Context

To understand the historical implications of the Maiyoo Keyoh and other Keyohs family groups, we need to understand the cultural contexts of territorial rights of the Stuart Lake Dakelh peoples, prior to the imposition of Indian Act laws and development of a treaty influence.

Stuart Lake Dakelh Culture

The Stuart Lake Dakelh Peoples (sometimes referred to as the 'Carrier') are part of a larger Athapaskan speaking group [4]. They are part of the larger Dakelh culture made of three regional groups:

- The Central Dakelh:

Traditionally spanning from the upper Fraser Valley (Lhtako, Lheidli Tenneh) to Cheslatta Lake (Cheslatta Nation) in the west.

- Southern Dakelh:

The associated territory typically stretches from Bowron Lakes in the east to the Western Chilcotin Valley (Ulkatcho).

- Northern Dakelh:

They are thought to occupy an area from Burns Lake (Ts'il Kaz Koh) extending to Moricetown and North to Takla Lake. (Carrier Sekani Tribal Council, [5]

Today the Stuart Lake Dakelh refer to themselves as the “Dakelh-ne”, which means, people who travel by water [6]. The Dakelh people are a strong group of hunters, where primary subsistence occurred through the hunting of large game, and the seasonal collection of salmon with trade networks to the coastal groups. The Dakelh people are also people of the forests, whereby cultural identity is rooted in the connections we find from the land. While the landscape tells the stories of our ancestors, it represents important indicators of good behaviour. As land serves to remind us of who are, where we came from, and why it must continue to be protected [7]. The protection that is very often carried forward through ancestral family lands passed down generationally through customary family lands known as Keyohs.

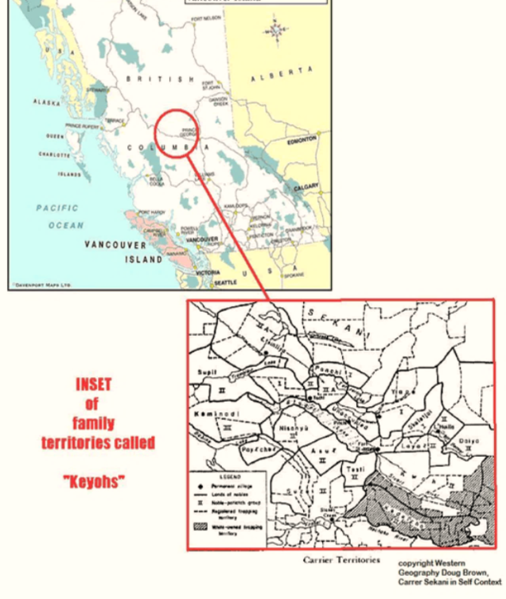

Customary Law: Keyoh Property Rights

Keyoh systems of the Stuart Lake region are a traditional Dakelh custom to manage lands and resources that is sustainable and equitable amongst family groups. Specifically, it is a land tenure system that pre-dates European settlement in what is now known as Canada. According to Mitchell (2002)[8], the "Carrier traditional territory is divided into smaller family-owned territories they called their Keyoh" (p.15). Moreover, the "Keyohs are the traditional land holdings of Dakelh (Carrier) people, and the land in all directions from Stuart Lake is divided into keyohs, some larger and some smaller than others. These keyohs predate the arrival of Europeans. Under the Dakelh law, the heads of our extended families have title to the keyohs. This title is not granted, delegated or derived from an Indian Band or some other authority. It has been passed down from one family head to his or her successor, generation after generation, for many hundreds of years." [9] This statement designed by Keyoh holders of the Stuart lake region, was made as an affirmation of continued occupation and cultural identity derived from their Keyohs.

What a Keyoh means to the Author

On a personal note about keyohs, I the author (Seraphine), have built a strong sense of connectedness to my family, through bonds shaped by activities on our keyoh. Hunting, berry picking, medicinal collection and general gatherings have given us a space to recognize that our land is the only variable in our lives that remains constant in a society where uncertainty and individualism are rampant. For many other cultures, land does not hold a sense of place and belonging in the same ways it does for Dakelh peoples. For many other cultures, the ways they have passed on memories is through photos, heirlooms, and property. However, for us, our land is our memories, it is a living memory that encapsulates our sense of where we came from through the stories of our ancestors etched onto the landscape. These etchings are then instilled through our customs and practices that we continue to act in our everyday lives on our land. Thus, instilling and reinstating our sense of security and belonging. This is not just about a general claim to the land; this is about the protection and preservation of our way of knowing and being within this world. Since many of our people suffer at the hands of colonial practice, the land remains to be the only true constant and a place to turn in peril. As my grandmother has repeatedly stated over the years, as her grandparents have stated to her, "you must look after the land so that it can look after you!". Any act that reflects selfishness where extraction of resources beyond our means is a direct violation of this law will inevitably lead us towards a cultureless hollow that has created directionless actions and identity crisis. This, in my opinion, is perhaps one of the more damaging colonial acts of violence directed upon Indigenous peoples. Displacement from land through assimilative practice perpetuates dependency and social sickness in our people. It is critical to understand that the land has survived our ancestors, and as a result, they remain apart of the landscape with an omniscient presence that continues to watch over our family here. For thousands of years it has survived our family, and with our unyielding efforts to protect and preserve our heritage and use sites, it will remain a constant to rely on, depend and seek solace in a world that seeks to dismantle Indigenous claims to sovereignty.

Infringements on Aboriginal rights

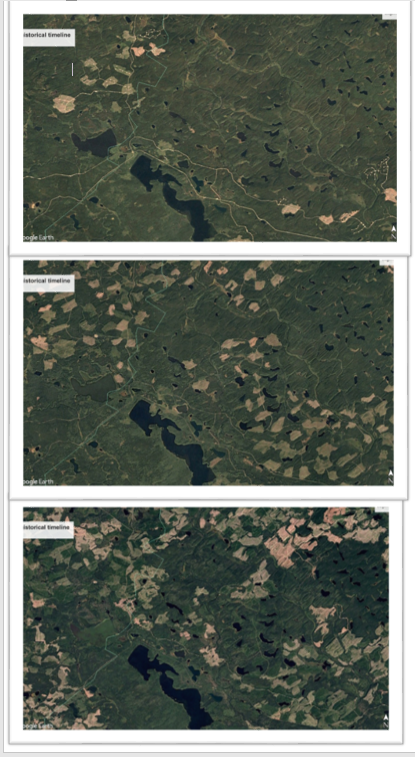

Unfortunately, with the exclusionary development of forest policy, the territory now has overlapping stakeholder interests with forest development. Since the early 1990s, the Keyoh was subject to rapid deforestation (See Figure on the right representing logging impacts from year 1984, 1996 and 2016) Whereby Cheif/Keyohwhadachun requested Jim Munroe to become the spokesperson and now CEO of the Maiyoo Keyoh Society, to support the advocation of accommodation for Aboriginal rights that are constitutionally protected as entrenched in the 1982 Constitution (rights to fish, hunt and trap) as clarified through R v. Sparrow R. v. [10] . However, with various blockades, there was little recognition of our rights to the land. Layers of bureaucracy create systemic impediment to gain meaningful consultation, especially when we consider the amounts of overlapping claims to the territory from neighbouring bands that resulted in the post-contact period that amalgamated groups and disrupted existing boundaries and neighbouring treaty alliances. As stated previously, the continued rate of logging on the Maiyoo Keyoh has negatively affected the families ability to continue using the land in the same patterns as done previously. More importantly, the creation of access has given access to the large game by both predators and hunters while large cut blocks on the keyoh have created habitat loss that eventually becomes replaced with tree farms. Roads are often not deactivated and smaller "spur" roads nearly 150 years to regrow, [11]. Furthermore, a case study analysis that measured the damages created by resource roads from logging was conducted with the Maiyoo Keyoh Society as a validation exercise found evidence of indirect and direct losses from the creation of resource roads. The study, named "Forestry and Road Development: Direct and Indirect Impacts from an Aboriginal Perspective." by Christine, M., Kneeshaw, D., & Beckley, Tom. Determined five main results from their research that explored how "an Aboriginal community interprets and responds to the increasing developments of roads in its territory" [12]. Their results found four major changes and challenges surrounding the creation and maintenance of roads created within the space of Indigenous customary lands:

- . Aboriginal: These can be divided into intra-, inter-Aboriginal community dynamics and general Aboriginal values (those which are not specific to the case study but which are Aboriginal issues in nature) effects.

- . Hunters in general (sports, poaching, and aboriginal hunters): Road development has facilitated hunting activities by rendering the territory more accessible. This is true for community members, other Aboriginal communities, as well as non-Aboriginal hunters.

- . Foreign: The forest industry and non-Aboriginal hunters were specifically identified as new groups with stakes in the development of roads on the territory. They are viewed as foreign by the forestry committee because they have not historically occupied or used their territory nor collaborated with the community for territorial use.

- . Territorial: Road development has affected local territorial dynamics by opening the region to use by everyone and changing the way it is viewed and perceived by users in general (Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples).

- Environment: The ecological impacts of roads were noted by the members interviewed including effects on: edges (forest composition, structure and health in edges), forest tree composition (more young trees, more

deciduous trees), dust, lakes (water composition), fish, and fauna (“the animals look for shelter”). Changes in Aboriginal community relationship to the environment were also noted by respondents.[12]

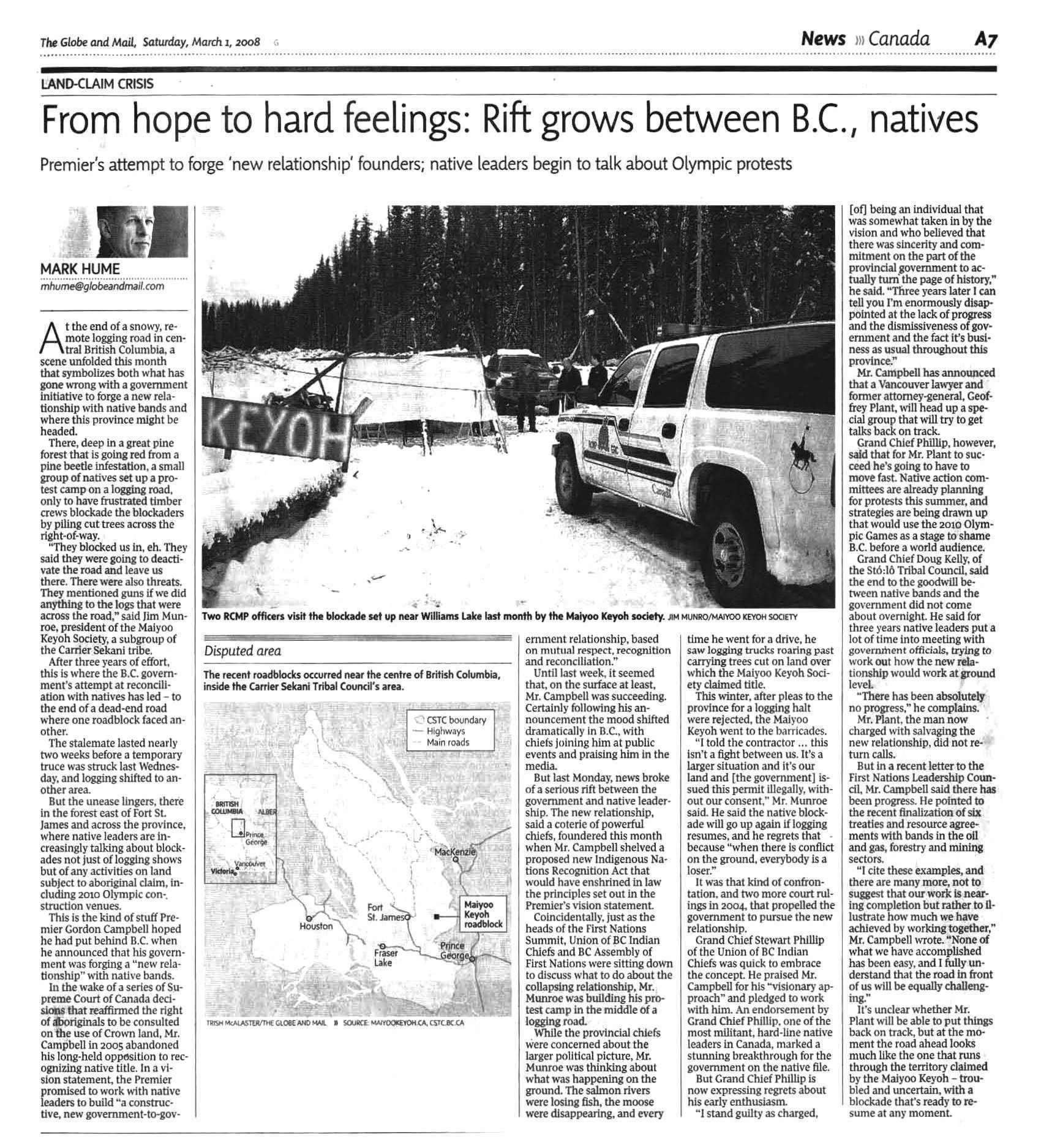

At one point the Maiyoo Keyoh Family Camped outside in a "lean-to" in -40-degree celsius weather, on the road flagged for development towards a proposed cut-block in 2008. This blockade set up by the Maiyoo Keyoh society was established to block proposed developments that would destroy our traditional use areas without accommodation or consent. Tensions escalated as the contractors were losing thousands by the day with our relentless efforts to protect the land. As a result, the contractor blockaded the road that gave us access to contact our families and run for supplies. This precipitated violence whereby a member "hitchhiked" down the Forest Service road to neighbouring families, and the community gathered to support our blockade with guns and other material to stand up for the family’s rights. To de-escalate this situation, the contractor and licensee quickly made a deal with the family to 'stop logging in that area and a moratorium that was later breached. Unfortunately, due to the careful wording of the contractor agreement, they continued unauthorized logging of the remaining cut block the family worked hard to protect. It was a tremendous loss for the family. See Maiyoo Keyoh news article: (note mistakes in article that state "near Williams Lake" this was closer to "Fort St. James."

Consultation: Whom do we consult?

You might be asking, what happened? Our current consultation practices, reinforced after the "new relationship" created to address the "war in the woods" that was common during the 1980s and 1990s. This era was known for political unrest that was marked with various forms of subversive actions such as direct actions stands; a more notable event that can signify changes during this period is known as the Oka Crisis in 1990. During the Oka crisis, developments of a golf course ensued violence and brought the Canadian militaries involvement [13]/. This event along with many others (eg. Gustafasen Lake [14], Unist'ot'en Camp [15] etc), decidedly marked the 2000s with a pressure to change developmental strategy. More importantly major case law such as Delgamuukw v British Columbia (1997) [16] and Haida v British Columbia (2004) [17] shifted the dynamics of the duty to consult towards greater accommodation of Indigenous peoples in BC. However, with overlapping territory boundaries, there remains confusion over whom to consult.

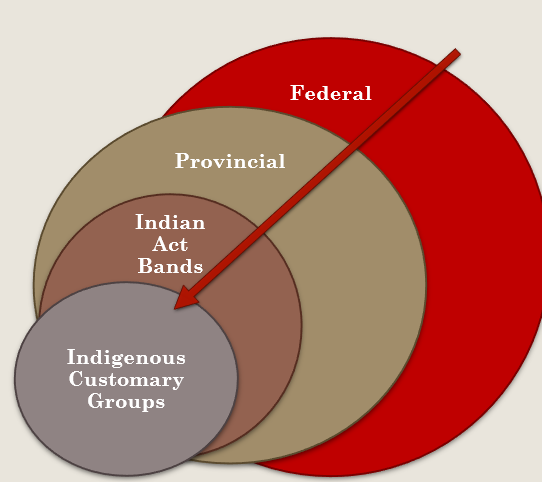

The current application for the duty consult recognizes the state-imposed governance systems, known as the "Indian Act Band'. However, due to limited capacities and response measures to deal with large densities of notifications and referrals, they are not always equipped to deal with the response time[1]. Further to this, the notification and referral process of consultation often occurs within very short time frames of 30 days for affected stakeholders. Further to this, it can also be argued that stakeholder interests over customary lands such as the MKS, is often overlooked. Within this case study, the band may even be seen as the "interested" stakeholder, where employees with decision-making power are employed under a system that benefits in monetary value. Additionally, employees continue to hold job security and stability through the band after the completion of developmental activities. While the dynamics and relationship to the land from Keyoh members are changed and disrupted.

One notable author, Som Pun (2016), studied the Tlazt'en people's limitations and opportunities with forest agreements at great lengths, highlighted some important points in relation to the Keyoh systems and the recognition of customary groups:

- The state-imposed a system of governance has not only created a continual system of state dependency, but also a deep division between certain community groups, particularly the elected Band Councils and the Keyoh holders, weakening the traditional systems of governance. (p.550) [18]

- The conflict that exists between bands and Keyoh systems is the root cause of mistrust, divisiveness, and conflict that continues to break apart social cohesiveness and self-sufficiency of the Tl’azt’en Nation that existed for thousands of year[18]

- The current approach in the consultation process seriously undermines the traditional roles and responsibilities of the Keyoh holders through the elected C&C. The Keyoh holders do not recognize C&C as their legitimate government representatives as they are elected and mandated under the Indian to represent only the small reserve lands which contradict the traditional system of governance. The government, on the other hand, does not recognize Keyoh holders as a legal government entity so it directly contacts the C&C rather than the Keyoh holders during the consultation process. [18]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Passelac-Ross, Monique; Smith, M. A. (2014): Accommodation of Aboriginal Rights. The need for an Aboriginal Forest Tenure. In D. B. Tindall, Ronald L. Trosper, Pamela Perreault (Eds.): Aboriginal peoples and forest lands in Canada. Vancouver: UBC Press, pp. 129–148.

- ↑ Wyatt, Stephen (2008): Indigenous , forest lands, and “aboriginal forestry” in Canada. From exclusion to comanagement and beyond. In Can. J. For. Res. 38 (2), pp. 171–180. DOI: 10.1139/X07-214.

- ↑ Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), [2004] 3 S.C.R. 511, 2004 SCC 73 from https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/2189/index.do

- ↑ Tobey, M.L. (1981) Carrier. Pages 413-432 in June Helm (volume editor) Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 6, Subarctic. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

- ↑ Carrier Sekani Tribal Council. (2007) A CSTC Background

- ↑ Carrier Linguistic Society. (2014). Nak'azdli Bughuni: Carrier Dictionary

- ↑ Sam, S. (2017), personal communication with Seraphine Munroe

- ↑ Mitchell, Rennel (2002). Treasures of the Carrier people: an introduction to Carrier material culture and research findings on the Parks Canada Athapaskan collection. Prince George, B.C.: Fraser-Fort George Regional Museum. 107 pp.

- ↑ keyoh Huwunline (2015) whom we are from http://keyoh.net/

- ↑ Sparrow, [1990] 1 S.C.R. 1075https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/609/index.do

- ↑ Morben, M. and M. Kirk, N. Farrer, D. Dolejsi, A. Sawden. 2009. Scenario Analysis for the Maiyoo Keyoh. Maiyoo Keyoh Society & the University of British Columbia. FRST 424, April.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Adam, M.-C., Kneeshaw, D., & Beckley, T. M. (2012). Forestry and Road Development: Direct and Indirect Impacts from an Aboriginal Perspective. Ecology and Society, 17(4). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04976-170401

- ↑ Oka Crisis (2013) from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/oka-crisis

- ↑ Gustafsen Lake, (2009) UBC, from http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/gustafsen_lake/

- ↑ Unist'ot'en Camp (2017) from https://unistoten.camp/

- ↑ Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, [1997] 3 S.C.R. 1010

- ↑ Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), [2004] 3 S.C.R. 511, 2004 SCC 73

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Pun, S. B. (2016). The implications and challenges of Indigenous forestry negotiations in British Columbia, Canada: The Tl’azt’en Nation experience. Journal of Sustainable Forestry, 35(8), 543–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/10549811.2016.1228071

dienous