Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/Illegal Logging in the Case of Behn v Moulton Canada

Brief Summary

On June 27, 2006 the Crown, as represented by the Ministry of Forestry of the Province of British Columbia, granted timber licenses and a road permit to Moulton Contracting Ltd. for harvesting timber in two areas of the territory of the Fort Nelson First Nation (FNFN). Members of FNFN set up a blockade to the area, stating that the Crown did not fulfill its duty to consult and therefore the licenses should be void. Both of the granted licenses were within the Behn family trapline area of the FNFN. [1]

The BC Supreme Court (2010), BC Court of Appeal (2011), and the Supreme Court of Canada (2013) held that individual members of the Aboriginal community did not have legal standing to assert collective rights in their defence; only 'the community' as a whole could invoke such rights. The courts also concluded that the community should have challenged the validity of the licenses at the time when they were issued, and that the community had failed to do that. [1][2]

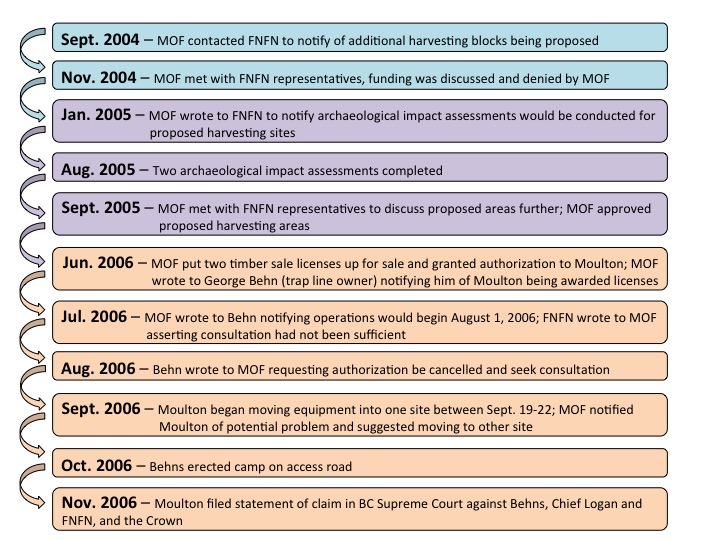

Timeline

Activities leading up to the filed Statement of Claim in BC Supreme Court by Moulton Contracting Ltd.

Historical Context

Fort Nelson First Nation

Dene and Cree descendants of the Liard River watershed located in northeastern British Columbia, the forks of the Muskwa and Nelson rivers situate the FNFN. REWRITE THIS SENTENCE IN STANDARD ENGLISH. FNFN is comprised of the historic location of 10 major village sites where 14 major families lived; these families both traded amongst each other and with other neighbouring Nations. [3]

FNFN is a party to Treaty No. 8 of 1899, which covers an area comprising parts of Alberta, British Columbia, Saskatchewan and the Northwest Territories. The majority of the FNFN traditionally organized themselves so that the rights to hunt and trap set out in Treaty 8 were exercised in tracts of land associated with different extended families. [1]

Treaty No.8

Treaty No. 8, is one of the eleven treaties that were negotiated between 1871 and 1921 and known as the numbered treaties. These treaties were highly influenced by the motivation from the MacDonald government to secure jurisdiction under the Crown in areas that were heavily inhabited by Aboriginal peoples, thus preventing the expansion and takeover by the United States. [4]

Signed June 21, 1899 between First Nations in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Northwest Territories and the Queen of England. British Columbia was later added to the treaty, signing in 1910 in exchange for freedom to live life undisturbed by settlers with the promise to share the land and live in peace with the neighbours. [1][3]

The signed Treaty No. 8 document led to formation of the Treaty 8 Tribal Association (T8TA) that is comprised of six First Nations communities, including that of FNFN. Originally drafted in September 2003, this was re-affirmed in June 2006 with stated commitment adhering to areas of culture, economic development, co-operation, self-governance, and land use planning and monitoring. [5]

Relationship with the Province of BC, Specific to Forestry

Speaking to the relationship with the Province of BC, specifically with respect to its Ministry of Forestry (MOF), prior to 2002 the duty to consult with FNFN and other First Nations was limited to the dated wording in the “Indian Act, 1985” and the “Constitution Act, 1982” [6]. The court case of Haida Nation v BC and Weyerhaeuser is marked as a turning point to the duty to consult between MOF and First Nations. [7] In large response to the court cases faced surrounding Aboriginal title and rights, the Province brought forward a new policy in 2003 with the creation of Forest and Range Agreements.

Although the Forest and Range Agreements (FRAs) are seen as a highlight of the positive movements by the Province to create better relationships with BC First Nations, Parfitt highlights that many of the first agreements, in essence created a binding agreement that prevented the FN from protecting their lands through processes such as blockades (INSERT A REFERENCE). Also noted regarding the first FRAs are the one-size fits all approach that was taken did not make sense since First Nations are diverse. Changes in 2006 to the FRAs came about due to the number of concerns raised by First Nations communities; however, the FNFN were still not satisfied with the changes and have yet to sign an FRA.

The FNFN as a community has been strongly opposed to outside industry harvesting timber on their traditional territory, despite agreements having been signed in other regions of Treaty No. 8. FNFN has put forward a written policy covering aspects of proper consultation and Aboriginal rights to the Province, and although it was reviewed the Province did not subsequently adopt it. [8]

Framing the Issue

Forestry Perspective

Looking at this case from a forestry perspective, the problems seem to lie within the areas of:

- The right of an individual or family to protect treaty rights within their territory

- The failure of duty to consult with the FNFN

- The irony in that although the Province was found to have failed to consult in its case against Moulton, the Court did not find that duty to consult was breached in the Behn v. Moulton case

1. Individual Rights

Currently, Sec. 35 of the “Constitution Act, 1980” upholds Aboriginal rights and a duty to consult with Aboriginal groups and individuals who have been given authorization by the collective [BAND? SPECIFY WHO 'THE COLLECTIVE' REFERS TO]. [9] The duty to consult is said to exist to protect the collective rights of Aboriginal peoples, and while a group can authorize an individual or an organization to represent it for the purpose of asserting its Aboriginal or treaty rights, as seen in this case, it does not provide ultimate decision-making power or an opportunity for those families with treaty specific rights.[1] Therefore, even when a family or individual may collectively hold specific rights to an area, without collective action from their community, their rights in that forested area are not recognized by representatives of the Crown.

2. Duty to Consult

The Province was found by the Crown to not meet standards in their duty to consult with FNFN. There is no upheld legal definition with respect to what it means to meet the ‘duty to consult’ obligation placed upon the Crown and this leads to unpredictable results. Without taking action through peaceful protests or litigation, grievances over the consultation processes may fall on deaf ears. Unfortunately, litigation requires understanding, time, and finances to pursue this route. It is not always accessible to a specific Aboriginal group.

3. Context of Court Cases

Perhaps the most interesting issue related to the act of illegal logging in this case are the differences in the context of the court. [10] While the Behns and FNFN both argued that there was an initial failure to consult by the Province previous to authorization to Moulton, the Crown disagreed. The Crown stated that this was held because neither FNFN nor Behn followed legal procedures, in that the proper documentation was not submitted by the date set. It seems ironic that the Crown then found the Province guilty of failing to properly consult with FNFN and Behn in the case: Moulton Contracting Ltd. v. British Columbia (2013).

Layering Perspective

This issue is framed from a forestry student perspective; however, this case also has issues in the areas of social justice, law, environment, and governance. Contributions in framing the issues related to these areas are encouraged and would be beneficial to a more encompassing case study review. Other areas outside the ones mentioned are also welcome to be explored within this case study. Consider perhaps the questions:

- What law defines Aboriginal rights and differences between those in treaty and those not in treaty?

- What are the impacts to the environment due to the silo format of governmental processes?

Implications

Environmental

The Province was found to not have consulted with FNFN, “in a manner sufficient to maintain the honour of the Crown”.[8] This finding is significant for future environmental impacts, as it requires a greater consultation process be provided not only with First Nations, but also within the Province in its Lands Department. Wildlife habitat concerns were raised by the Lands Department, and subsequently ignored – as was the request by Behn for an Environmental Impact Assessment.[8] By finding the Province at fault for failure to consult, this provides incentive and precedent for greater collaboration and integration when considering land use planning.

Economic

In addition to finding the Province failing to uphold its duty to consult, it found that FNFN had made it clear that they had insufficient technical capabilities to address the proposed amendments initially made by the Province and that this should have been addressed.[8] While the Crown insures that the Province is not required to financially assist the FNFN in increasing its technical capacity, the Crown made note that more should have been done to accommodate the issue at hand. This finding helps to ensure that in future discussions between the Province and FNFN regarding land processes, a more just and transparent discussion would proceed. Specifically, this is ideal for discussions that relate to economic and equitable profit for land proposals and amendments.

On the basis of future business ventures and relationships between FNFN and industry partners, finding the Province not liable to Moulton under its TSL agreement (section 14.01) gives rise to new relationships outside the Province.[8] Businesses, especially within the forestry sector, may be more active in pursuing their own relationships with FNFN without the government, as the liability of a blockade lies with the company purchasing a TSL. It can be assumed that this liability on the company could extend to other areas of industry following suit to also pursue relationships solely with FNFN to ensure their own liability is protected.

Social

Moulton claimed against the Behns, that an intentional interference with economic relations and unlawful conspiracy were founded on two types of unlawful acts:

- Criminal mischief under s.430 of the Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46; or

- An unlawful act in creating and maintaining a blockade across a forestry road[8]

The Behns were not found to have committed criminal mischief. That would have required the Behns to pay damages. The verdict upholds the practices of peaceful blockades which are a means of protesting used by Aboriginal communities and members. Peaceful blockades are a key tactic and holding within Indigenous movements worldwide, and the outcome of this case gives further support to both current and future movement to be seen not as a criminal act, but of one that warrants readdressing the issue at hand.

Cultural

In regards to treaty rights, although it is predominately seen as a collective right, an example through the Grand Council of the Crees and Cree Regional Authority have made distinction between authority rights, including that of the individual.[1] The Supreme Court of Canada have left open the possibility that individual members may have the authority to assert specific Aboriginal or treaty rights, such as in the case of a greater interest in the protection of rights on their traditional family territory.[2][1]

Recommendations

Forestry Perspective

In “New Partners: Charting a New Deal for BC, First Nations and the Forests We Share”, the recommendations for true partnership regarding forestry between the Province and First Nations still stand relevant today: [7]

- Half of every dollar collected by BC in timber-cutting or stumpage fees be shared with First Nations

- That the Province turn over defined areas of forestland to First Nations under renewable forest tenures

- The Province reduces stumpage fees to First Nations receiving new forest tenures

- The Province aims for a co-management system of forests

- Equitable share of forest revenues and resources is provided to First Nations from the Province

The legal system enforced upon the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island, has failed to realize the implications of colonization on the pre-existing systems.[11] Where previously extended families may have been responsible for portions of land, the assimilation and aggregation by governmental systems has led to uncertainty of land title within legal proceedings. The inability to address disagreements over Aboriginal and treaty rights through efficient means and just consultation processes creates risks beyond the litigation.[10] One of those risks is the collective opinion that instead of embracing Crown statements of reconciliation and the honouring of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) Calls to Action, the Crown is instead hiding behind these statements.[12] Part of the TRC calls to action include implementing the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), such that Article 11 would be applicable in this case: the right to maintain and protect their culture. [13] Although the Crown’s position on both TRC and UNDRIP have come after this initial case study began, both are relevant in how we move forward in addressing similar case studies.

Layering Perspective

The recommendations provided based on this case study are from those of a forestry background. What recommendations may be provided in other areas that may be applicable, such as:

- Law

- Environment

- Social Justice

- Economics

- Sociology

- History

- Anthropology

- Philosophy

Other Cases of Interest

The following case studies listed are those that have set a precedent or created changes to Aboriginal title, rights, and consultation processes. While this is not an exhaustive list, this list is meant to encourage further readings in the area and help provide further information for potential layering perspectives.

- Garland v. Consumers’ Gas Co 2004

- Haida Nation v. British Columbia 2004

- Mikisew Cree First Nation v. Canada 2005

- Beckman v. Little Salmon/Carmacks First Nation 2010

- Delgamuukw v. British Columbia 1997

- R. v. Van der Peet 1996

- Taku River Tlingit First Nation v. British Columbia 2004

- Komoyue Heritage Society v. British Columbia 2006

- R. v. Sparrow 1990

- R. v. Sundown 1999

- R. v. Marshall 1999

- R. v. Sappier 2006

- R. v. Power 1994

- R. v. Conway 1989

- R. v. Scott 1990

- Canam Enterpries Inc. v. Coles 2000

- Blencoe v. British Columbia (Human Rights Commission) 2000

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Behn v. Moulton Contracting Ltd., 2013 SCC 26, [2013] 2 S.C.R. 227

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Slade, T. (2015). Moulton Contracting Round 2: Crown Liability & Duty to Consult. Message posted to http://canliiconnects.org/en/summaries/36151

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 Chief Dickie. (n.d). Fort nelson first nation., 2017, from http://www.fortnelsonfirstnation.org/

- ↑ Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. (2013). The numbered treaties (1871-1921)., 2017, from https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1360948213124/1360948312708

- ↑ Treaty 8 Tribal Association. (n.d.). Treaty 8 agreement., 2017, from http://treaty8.bc.ca/treaty-8-accord/

- ↑ Hanson, E. (2009). Constitution act, 1982 section 35., 2017, from http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/constitution_act_1982_section_35/

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 Parfitt, B. (2007). In Rehnby N. (Ed.), True partners: Charting a new deal for BC, first nations and the forests we share. Vancouver, BC: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Tyler, K., & Jones, S. (2013). Moulton contracting ltd. v. british columbia 2013 BCSC 2348, BC supreme court, (saunders J)., 2017, from http://blg.com/en/News-And-Publications/Publication_3628

- ↑ Gilbride, B., & Willms, C. (2013). Supreme court of canada rules self-help remedies an abuse of process in behn v. moulton contracting., 2017, from http://canliiconnects.org/en/summaries/36151

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 Land, L. (2014). Creating the perfect storm for conflicts over aboriginal rights: Critical new development in the law of aboriginal consultation. The Commons Institute

- ↑ Ragsdale, J. (2004). Individual aboriginal rights. Michigan Journal of Race & Law, 9(Spring), 323.

- ↑ Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to action. Winnipeg, Manitoba: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2012.

- ↑ UN General Assembly. (2007). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples UN General Assembly.

| This conservation resource was created by Braydi Rice. |