Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/2023/Degradation of Marine Resources Off the Coast of British Columbia, Canada: An Assessment of the Co-Management of the Gwaii Haanas National Marine Conservation Area Reserve

Summary of Case Study

Significance

The coastal ecosystem in British Columbia is out of balance[1]. Fisheries are edging closer and closer to collapse, wildlife are going extinct, and vital ecosystems are disappearing[2]. With $60 million being granted for collaborative marine conservation and economic development on the North Coast of British Columbia on December 5, 2023, there is immense opportunity for Indigenous communities to play a meaningful role in the protection of marine areas[3]. The Gwaii Haanas National Marine Conservation Area Reserve is the first of its kind, a marine protected area (MPA) that is co-managed by both the Council of the Haida Nation and the federal Government of Canada[4]. Through this case study, I hope to provide support for the success of the co-management of the Gwaii Haanas National Marine Conservation Area Reserve, with management shared between the Council of the Haida Nation and the federal Government of Canada, and highlight the importance of local peoples playing a role in decision-making when it comes to the resources they know the best.

Keywords

Council of the Haida Nation; coastal resources; marine resource management; Indigenous planning; co-management; Marine Protected Areas (MPAs); community-based natural resource management (CBNRM); coastal ecosystems; marine degradation

Introduction

Land Acknowledgement

I would like to firstly acknowledge that this case study was researched, formulated, and assessed on the traditional, ancestral, unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) First Nation, Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), Stó:lō and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil- Waututh) Nations. I would also like to acknowledge that my case study examines the traditional, ancestral, unceded lands and waters of the Haida Nation, though I myself, am not of Haida descent.

Positionality

I was born in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, which is the traditional territory of the Anishnaabeg, specifically the Garden River and Batchewana First Nations and the Metis Nation of Ontario, within lands protected by the Robinson Huron Treaty of 1850[5]. My father is also from Sault Ste. Marie, while my mother is from Taiwan. I would like to acknowledge that I am an uninvited settler on Turtle Island, and I am not necessarily Indigenous to any place, as my parents both come from different backgrounds. I also acknowledge that I am incredibly privileged in that I am immune to the racial discrimination which Indigenous peoples experience to this day. Through my actions, my work, and my life, I aim to be more respectful, educated, and humble about my place in this world. Though I was born in Anishnaabeg territory, my family moved to Saturna Island, British Columbia when I was 4 months old. Saturna Island is an island of only 300 permanent residents, the traditional territory of the Tsawout and Tseycum, of the WSÁNEĆ Nation[6]. It was there that my interest in the ocean first began, as my father worked as a coast guard and later a whale watching captain. I care deeply about the well-being of the ocean, which has led me to my case study topic.

Background

Location

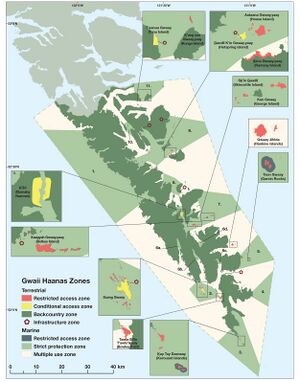

The scope of this case study lies within the West Coast of what is now British Columbia, Canada, with a focus on the Coastal First Nations, which formally includes the member nations Wuikinuxv, Heiltsuk, Kitasoo Xai’xais, Nuxalk, Gitga’at, Gitxaala, Metlakatla, and the Haida Nation. Some of the communities on Haida Gwaii are Old Massett, Skidegate, and Council of the Haida Nation[7], as pictured in the map below.

This case study focuses on the Council of the Haida Nation, the elected government of the Haida Nation in the archipelago of Haida Gwaii. Canada has the longest coastline of any country on the planet, of which British Columbia's coast makes up 10%[8]. There are numerous components of British Columbia's coastline, including but not limited to the Pacific Rim on Vancouver Island, inlets, mountainous regions, intertidal zones, and deep sea areas. For the purpose of this case study, I will be focusing on the 5 Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in British Columbia, which are the 1) SGaan Kinghlas-Bowie Seamount, 2) Gwaii Haanas National Marine Conservation Area Reserve and Haida Heritage Site (Haida Nation), 3) Hecate Strait/Queen Charlotte Sound Glass Sponge Reefs, 4) Scott Islands marine National Wildlife Area, and 5) Endeavour Hydrothermal Vents MPA[2].

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are designated areas that are meant to protect marine ecosystems[2]. As previously mentioned, there are 5 MPAs in British Columbia, each with unique rules for allowed human activity such as fishing and harvesting. MPAs are recognized as "one of the most effective tools to protect ocean ecosystems, rebuild biodiversity, and help species adapt to climate change — but only when they are strongly protected"[2]. The legal component of MPAs is what provides them with strength, in the injunction to exclude others from using the marine resources in the protected areas. That being said, as the existing MPAs in British Columbia protect the coastline (Gwaii Haanas National Marine Conservation Area Reserve) or deep sea marine areas, it can be more difficult to manage and regulate than a traditional forest. The Gwaii Haanas National Marine Conservation Area Reserve is the only MPA in British Columbia co-managed with a First Nation.

To provide clarification, marine resources include biological diversity (marine biodiversity), ecosystem services from marine ecosystems, such as marine coastal ecosystems and coral reefs, fish and seafood, minerals (for example deep sea mining), oil and gas, renewable energy resources, such as marine energy, sand and gravel and tourism potential. Though marine resources encapsulate a plethora of different issues, the marine resources that this case study focuses on are fish and seafood and ecosystem services.

History

Colonization

Though this case study does not offer the space required to dive deeply into the history of settler colonialism and all of the impacts of the ongoing process of colonization, it is important and necessary to address the lack of treaties signed in British Columbia compared to the rest of Canada. Very few treaties were signed in British Columbia, meaning that most British Columbians are all on unceded, stolen lands[9]. However, all oceans, lakes, rivers and streams are under federal jurisdiction[10]. With federal jurisdiction over marine resources, concerns about how these resources are being managed are numerous, as oftentimes, local peoples are the ones who know and understand the resource the best[1]. These concerns have been validated by the state of various marine resources off British Columbia's coast, with not only environmental impacts being observed within these ecosystems, but also socio-economic and socio-cultural impacts being caused by marine pollution[11], marine traffic[11], overfishing[12], and more.

Indigenous Peoples' Connection to the Sea

Many Indigenous peoples have historically felt, and continue to feel a strong relationship to the natural environment[13]. Understanding land as a teacher, rather than a resource is often at the root of Indigenous worldviews[14]. With British Columbia's long coastline, many Indigenous nations and communities in British Columbia have a deep connection to the ocean. Additionally, coastal Indigenous peoples eat nearly four times more seafood per capita than the global average, and about 15 times more per capita than non-Indigenous peoples in their countries[15]. However, consumption of seafood is not the only way that coastal First Nations feel connected to the sea. The marine planning document created by the Haida Nation in 2007 sums up the relationship between the Haida and the sea beautifully with their Marine Vision in Towards a Marine Use Plan for Haida Gwaii:

Haida culture is intertwined with all of creation in the land, sea, air and spirit worlds. Life in the sea around us is the essence of our well-being, and so our communities and culture.

Yet here, as around the world, an insatiable human appetite is depleting the oceans. Some species are diminished or gone, and many habitats are impoverished. We know that our culture depends on the sea around us, and that the well-being of every community and Nation is at risk. It is imperative that we bring industrial marine resource use into balance with, and respect for, the well-being of life in the sea around us.

We must take steps today to achieve a future with healthy intact ecosystems that continue to sustain Haida culture, communities, and an abundant diversity of life, for generations to come.

This vision demonstrates how deeply connected and intertwined the Haida people are to the ocean. Not only does the well-being of the sea matter to them greatly, but life in the sea directly impacts the well-being of the Haida Nation. Life begins and ends with the ocean for the Haida people[16]. Even the Haida's creation story tells that the Haida people came from the sea[17].

Tenure arrangements

The tenure arrangements of the Gwaii Haanas are increasingly complex. As the waters of Gwaii Haanas are officially and legally MPAs, there are restricted access zones, strict protection zones, and multiple-use zones, as depicted in Figure 1[18]. Figure 2 demonstrates how these areas can have differing bundles of rights, depending on the use of the area. Even though some of these areas are restricted, Indigenous peoples have the right to access the waters and harvest fish anywhere, as long as it is for traditional use. Another example demonstrated in Figure 2 is that commercial floating accommodations are not permitted in any area of the Gwaii Haanas, unless operated by and for Gwaii Haanas itself. Contrastingly, Indigenous peoples do not simply have the right to fish anywhere and sell their harvest without a license - if they hold a Status Indian identification card, they may harvest without a license, but only for food, social, or ceremonial purposes; and only within areas they can prove their First Nation traditionally used[19]. In Canada, aboriginal title and rights are recognized and affirmed under Section 35 of Canada’s 1982 Constitution Act. Additionally, in 2004, the Supreme Court of Canada found that the Haida have a strong prima facie case for aboriginal title to all of Haida Gwaii[20], meaning that it should be accepted as true until proven otherwise.

As previously mentioned in the Background section, in 1993, the Haida Nation and the federal Government of Canada entered into an agreement that indicated two distinct authorities for the management of Gwaii Haanas[21]. The Haida Nation currently collaborates with the federal government to manage 3,500km² through the Archipelago Management Board, which is made up of four members. Two members of the Board represent the Council of the Haida Nation, while two represent the Canadian government. All board decisions are made by consensus[21]. In 2010, the Haida reached an agreement with the federal government to also protect the marine areas off of the coast of Haida Gwaii, now known as the Gwaii Haanas National Marine Conservation Area Reserve and Haida Heritage Site. Two more Board members were appointed, one from the Department of Oceans and Fisheries to represent the federal government, and one from the Council of the Haida Nation to equitably manage the marine resources[22]. However, a crucial component of tenure is that even though the Archipelago Management Board exists to deliberate and make decisions about the management of the waters and the land in Gwaii Haanas National Park, Marine Conservation Area Reserve, and Haida Heritage Site, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans still has ultimate decision-making power[23].

An additional case study that represents the struggle over marine resources between the Haida Nation and the federal government is the case of the herring in Haida Gwaii waters. Jones et al.[22] discuss the decades-long effort of the Haida Nation to protect herring stocks off of the coast of Haida Gwaii, where herring stocks were continuing to decrease in Haida Gwaii waters year after year. The Minister of Fisheries and Oceans decided to move forward and re-open the Gwaii Haanas for commercial herring fishing in 2014, despite staff from Fisheries and Oceans Canada recommending against it due to insufficient evidence for the recovery of the herring in those waters[22][23]. The case becomes increasingly complex because the year prior to this decision, commercial fishermen had reached an agreement with the Haida not to fish in the area. The Council of the Haida Nation eventually used litigation to stop the commercial fishing of roe herring in Haida Gwaii waters, and was successful in 2016[23][24]. This has been a major point of disagreement for the Archipelago Management Board[22], and though the issue has since been resolved, remains a bad reminder of the negative aspects of the relationship between Haida and the federal government.

The below table outlines the bundle of rights that members of the Council of the Haida Nation hold within the Gwaii Haanas. Though the bundle of rights for the Council of the Haida Nation is relatively complex, the table has been simplified to provide the most accurate representation of my findings.

| Rights | Haida Nation |

|---|---|

| Access | Yes - Traditional use is allowed in all zones, consistent with the Haida Constitution and section 35 of the Constitution Act[4] |

| Withdrawal | Partially - allowed for Indigenous harvesting, but not for sale. See Figure 2 for more detail. |

| Exclusion | Yes - the members of the Archipelago Management Board vote on who may be legally excluded from the area, and two members of the Board represent the Council of the Haida Nation. May be more difficult to enforce because of the marine area. |

| Management | Yes - co-management is practiced between the Council of the Haida Nation and the federal Government of Canada |

| Alienation | No - the Haida Nation does not have the right to transfer co-management privileges to another entity |

| Duration | No - the co-management of the Gwaii Haanas is not time-limited |

| Bequeathe | Yes - members of the Haida Nation can pass down their rights to their family members, but the appointed Board members cannot pass down their positions on the Board to their families. |

| Extinguishability | N/A - this does not apply because the ocean is not technically owned by one entity, and therefore does not provide the possibility of any entity receiving compensation. This is the main way that this case differs from other case studies discussed in FRST522. |

Institutional Arrangements

As the oceans, lakes, rivers and streams are all under federal jurisdiction in Canada, the main management authority in this case is the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO). With the addition of co-management of the Council of the Haida Nation in 1993, the Haida Nation also has the power to observe and report activities within the Gwaaii Haanas. The Parks Canada website states that "Parks Canada and its partners are committed to maintaining the ecological integrity of Gwaii Haanas"[25], though it does not explicitly state the co-management practices that are implemented in Gwaii Haanas in conjunction with the Haida Nation. In addition to the institutional arrangement of the Gwaii Haanas agreement[26], there are also other Indigenous-led initiatives (such as the Coastal First Nations Great Bear Initiative and the First Nations Fisheries Council) fighting for the protection of their traditional lands and waters. These institutions attempt to join ancient Indigenous wisdom with modern science to ensure a healthy ocean future[27], through the braiding of traditional ecological knowledge and Western worldviews[13]. For Indigenous peoples and communities, partnering with the federal government is a way in which they can exercise their rights and move towards a more decolonial future.

Stakeholders

Affected Stakeholders

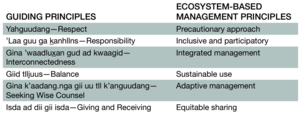

The most directly affected stakeholders in this case study are the Haida People, represented by the Council of the Haida Nation. As their community lives along the coast of Moresby Island, the Southern island of the Archipelago of Haida Gwaii, they live on the resources that the ocean provides - whether it be herring from the fisheries, shellfish from the intertidal zones, or various species of fish off the coast, as has been mentioned before, life begins and ends with the ocean[16]. The main objectives of the Haida in relation to this case study are to preserve the biodiversity of marine resources in the Gwaii Haanas and ensure that their cultural rights to harvest for traditional use are being protected[28]. Figure 3 outlines the guiding principles and ecosystem-based management principles of the Council of the Haida Nation and the federal Government of Canada respectively in the Gwaii Haanas Gina 'Waadluxan Kilguhlga Land-Sea-People Management Plan. The power that the Council of the Haida Nation holds in the case of the Gwaii Haanas National Marine Conservation Area Reserve and Haida Heritage Site is quite great, especially in comparison to other MPAs which have no Indigenous involvement at all, as well as other Indigenous nations who do not have legal rights to the land/waters that they live close to. They have legal power to co-manage the Gwaii Haanas because of the Gwaii Haanas agreement[26], but as was described in the case of the roe herring, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans still has ultimate power in decision-making. The Council of the Haida Nation has the most to lose, as the Haida are dependent on the well-being of the marine resources in the Gwaii Haanas, therefore they may be categorized as the primary affected stakeholder.

Interested Stakeholders

There are multiple interested stakeholders in this case study, including but not limited to commercial fishermen, environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs), the federal government, and the provincial government. The main relevant objective of the commercial fishermen is that they wish to make a profit. Jim Pattison, for example, is a billionaire who practically owns a monopoly on fishing licenses in British Columbia[29]. Commercial fishermen and company owners like Pattison can exercise their power easily when they practically control British Columbia's fisheries. Though there are other stakeholders who fall under the commercial fishermen label, it's important to acknowledge the inequities of such an actor in these situations. With that being said, the Haida Nation can combat commercial fishermen and restrict them from legally being able to fish in their protected areas. Unfortunately, much of the time, commercial fishermen do not completely understand Indigenous rights, as we saw in 2020 on the opposite coast of Canada in Nova Scotia. The argument that they often provide is that if Indigenous people can fish in these areas, they should be able to as well. As for ENGOs such as Laskeek Bay Conservation Society, they are interested in the preservation of marine wildlife and supporting Indigenous peoples in their decolonial efforts. However, ENGOs don't have as much power in this case study as they did in other cases, such as the Timber Wars[30], because the Indigenous peoples themselves in the case of the Gwaii Haanas have quite a bit of power already. Additionally, it's unclear based on the existing literature if the Council of the Haida hires outside help (such as ENGOs) to write grants and other administrative tasks. The federal government and the provincial government both have similar objectives, which are to stay in office - in simpler terms, they want to make as many of their citizens as happy as they can. Another goal of the government is to do what's best for the country and/or the province. This can prove to be complicated, especially in cases such as the Gwaii Haanas roe herring case, where the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans wanted to make money and be re-elected in office[22]. The choice that the Minister made was to support the commercial fishermen instead of the Haida -- leading to a court action which ended up in favour of the Haida[24]. The federal government holds enormous power, as the government has legal jurisdiction over all lakes, oceans, rivers, and streams in Canada[10] - and the Minister has ultimate decision-making power. There are many interested stakeholders in this case that stand to benefit/lose from the management of Gwaii Haanas, but it's important to remember that the Haida Nation is the most heavily impacted stakeholder of all.

Discussion & Assessment

Gwaii Haanas

The case study of the Gwaii Haanas is an exemplary case of co-management between the federal government and a local First Nation. As the Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve is the first of its kind[4], with protection from the mountaintops to the sea floor, it provides an example for future protection in British Columbia, Canada, and beyond. As was previously discussed, one critical issue is the continued power of the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, a federal representative, in making decisions about this space[22]. This case from 2015 can be categorized as the largest failure of the co-management of the Gwaii Haanas Marine Conservation Area Reserve[22], but the Haida are moving forward from this incident and working hard to conserve, preserve, and protect the biodiversity in their traditional waters. Despite some discrepancies, the co-management of the Gwaii Haanas has been relatively successful. Coupled with being the first protected area of its kind in Canada, it's important to acknowledge that there have likely been growing pains since its adoption 30 years ago. Additionally, the inclusion of Indigenous peoples and perspectives is not the end goal, but instead a starting point of reconciliation. Through management practices such as the Gwaii Haanas, where local people are being devolved power from the federal government, this can also be a way of slowly unwinding colonialism and the atrocities that happened, and continue to happen in what is now Canada. This case does not only address the management of natural resources, but also the healing of Indigenous ways of being, knowing, and learning.

The legal framework of MPAs means that some of our most vulnerable and necessary marine ecosystems receive legal protection. However, it's also important to acknowledge that the reason why legal protection is needed is because of the way that we have mistreated and addressed the ocean and the gifts it provides with a Eurocentric mindset[1]. Additionally, most of the MPAs in British Columbia do not include Indigenous inclusion in their management, as the Gwaii Haanas is the only MPA out of five which includes Indigenous management.

Existing Literature

Much of the existing literature surrounding MPAs and Indigenous communities comes from Ban et al.[28], discussing the contrast between "no-take MPAs" and the "exclusion of commercial and recreational fisheries while allowing for Indigenous fishing"[28]. The Eurocentric literature surrounding MPAs has historically been that nobody should be allowed to fish anywhere in MPAs, however, this has strong cultural implications and is yet another example of the ongoing process of colonialism impacting communities today. Two Indigenous communities, the Gitga'at and the Huu-ay-aht, were interviewed in 2008, members were asked about their perspectives on marine management practices. These two communities both supported the "exclusion of commercial and recreational fisheries while allowing for Indigenous fishing" as a way of protecting the fish stocks. To support this point of view, Indigenous peoples have lived within a sustainable, resilient system with the ocean since time immemorial, with a strong understanding of the Honourable Harvest[13], and taking only what they need. When European settlers came to Turtle Island, they began viewing the natural resources as something to be exploited, rather than something to be cherished[13]. Commercial fishermen, and billionaires like Jim Pattison, are not fishing and harvesting other marine resources with respect or gratitude, but instead are depleting the marine resources off of British Columbia's coast at an unsustainably fast pace. One way that Indigenous peoples are trying to combat this in non-protected areas is by purchasing the licenses themselves so that non-Indigenous people cannot obtain them[28]. Though this is not an ideal scenario at all, the Indigenous peoples local to coastal British Columbia are sacrificing their own funds to ensure that marine resources will be sustainably harvested.

Cultural Revitalization

Though it has previously been mentioned, the impact of co-management practices such as the case of Gwaii Haanas is not only beneficial for the preservation and protection of marine resources in the area but the impact on cultural revitalization can not be overstated. Many Indigenous nations, including the Council of the Haida Nation, are using marine conservation as a tool to fight oppression and heal from legacies of colonialism[31]. Balancing Western knowledge and traditional ecological knowledge has been a way that Indigenous knowledge is being incorporated as a necessary role in decision-making, and though it's not quite where it needs to be, Indigenous inclusion in areas such as the Gwaii Haanas is a good place to start. Being able to sustainably manage the resources that they are so deeply connected to is a method of healing and reconnecting with the land and the sea. Having Indigenous nations and communities have autonomy over their traditional territories is crucial for meaningful reconciliation.

Opportunities

With $60 million being set aside by the provincial government towards collaborative marine conservation and economic development on the North Coast of BC at the end of 2023[3], there is an immense opportunity for Indigenous inclusion to be further involved in the management of natural resources. Additionally, the decision to fund further protection with MPAs may help the Archipelago Management Board to realize its vision of having all positions in the Gwaii Haanas field unit be filled by members of the Haida Nation. The current manager of the Park Reserve is Haida, however, having Haida people employed in all positions would not only help with job security and food security, but also with moving forward with reconciliation, in supporting Indigenous peoples to reclaim taking care of the resources they feel so connected to[21]. Another, more general opportunity of the case study of the Gwaii Haanas is that it may help provide the structure and framework for future spaces to be similar to the Gwaii Haanas with respect to the co-management and Indigenous participation. With more money being allocated to MPAs, hopefully, the future of MPAs will continue to incorporate Indigenous teachings and knowledge, as local people often are the ones who know the resource the best - so they should also be the ones with the rights to sustainably manage it.

Recommendations

Before I share my recommendations, I'd like to acknowledge that my understanding of this case study is not comprehensive. I have not spent any time in Haida Gwaii myself, nor have I worked for the federal government, so I do not fully know and understand the complexity of this case study. With that being said, from an outsider's perspective, I offer my recommendations surrounding this case study.

In short, my recommendations are as follows:

- Meaningfully incorporate more Indigenous perspectives into decision-making

- Include Indigenous peoples and perspectives at the beginning of decision-making processes rather than at the end

- Increase legally protected areas (MPAs) with Indigenous co-management and/or management

- Strengthen legal protection for environmental resources

- Increase funding for Indigenous management of natural resources

My biggest recommendation surrounding the Gwaii Haanas case study is that Indigenous perspectives need to be more strongly incorporated into decision-making, especially when it comes to local resources[1][32]. Though we see the beginning of this movement with the Gwaii Haanas being a starting point for the co-management of an MPA, there is immense opportunity for power being devolved to Indigenous communities, especially with additional funding coming in to support marine conservation[3]. Additionally, we need more meaningful inclusion of Indigenous perspectives and knowledge, which we can ensure by consulting Indigenous peoples and including Indigenous peoples in the continued management of resources, rather than simply asking them to sign off on projects that have been completely created using Western knowledge.

Although this case study has demonstrated the complexity of legal protection and co-management methods, I do believe that we need to designate more MPAs with legal protection. With the $60 million awarded towards this goal[3], it's likely that this will be taking place sometime in the near future in British Columbia. However, increasing legally protected areas is not the only important component of this recommendation. I believe that Indigenous co-management and/or management of these areas is crucial, if not completely necessary. Indigenous peoples have sustainably managed these resources since time immemorial, and the balance of the planet has only become skewed because of the greed of capitalism that comes with Western ways of living. As a Eurocentric society, we have a lot to learn from Indigenous peoples in the ways that they view the world.

Finally, more funding needs to be allocated towards the Indigenous management of resources. We cannot continue to expect Indigenous peoples to volunteer their time for the greater good when we are not willing to provide compensation. With more funding comes more opportunities for successful co-management stories, such as the Gwaii Haanas and the Indigenous Guardians program, which is funding that "provides Indigenous Peoples with a greater opportunity to exercise responsibility in stewardship of their traditional lands, waters, and ice"[33]. Though throwing money onto a problem is not necessarily the "quick fix" that it may seem to be, I believe that funding, paired with meaningful Indigenous engagement and management, and more legally protected areas would help lead us to a better, more sustainable future.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Ban, N. C., Picard, C., & Vincent, A. C. J. (2008). Moving toward spatial solutions in marine conservation with Indigenous communities. Ecology and Society, 13(1). https://www.jstor.org/stable/26267930

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Acuña, C. (2022). Marine protected area 101: An introduction to MPAs. Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society British Columbia. https://cpawsbc.org/mpa-101-an-introduction-to-mpas/

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Smith, Jimmy (December 5, 2023). "B.C. supports collaborative marine conservation, economic development on North Coast". Government of British Columbia.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Parks Canada (November 1, 2018). "Gwaii Haanas Gina 'Waadluxan KilGuhlGa Land-Sea-People Management Plan 2018". Parks Canada.

- ↑ Tourism Sault Ste. Marie (2021). "Indigenous Tourism". Tourism Sault Ste. Marie.

- ↑ SIMRES (2020). "Saturna Island". SIMRES.

- ↑ Coastal First Nations (2022). "Our People". Coastal First Nations.

- ↑ Statistics Canada (2016). "International Perspectives". Statistics Canada.

- ↑ Government of British Columbia (2023). "History of Treaties in B.C." Government of British Columbia.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Government of Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada. (2010, September 22). Long-term fisheries arrangements in British Columbia and Yukon | Pacific Region | Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Government of Canada. https://www.pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/reconciliation/arrangements-ententes-eng.html

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Government of British Columbia. (2020). What we heard on marine debris in B.C. Government of British Columbia. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/waste-management/zero-waste/marine-debris-protection/marine_debris_what_we_heard_report_final_web.pdf

- ↑ Faggetter, B. A. (2008). Review of the environmental and socio-economic impacts of marine pollution in the north and central coast regions of British Columbia. Ocean Ecology. https://data.skeenasalmon.info/dataset/8a76d76b-6da9-4982-9ffb-607b6bfd8bc0/resource/2ec22aeb-1e8e-4983-8307-9ef9c9ba23bf/download/faggetter-2008-review-of-impacts-marine-pollution-north-and-central-coast.pdf

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Kimmerer, R. W. (2013). Braiding sweetgrass. Milkweed Editions.

- ↑ Simpson, L. B. (2014). Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3(3), Article 3. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/22170

- ↑ Cisneros-Montemayor, Andrés M.; Pauly, Daniel; Weatherdon, Lauren V.; Ota, Yoshitaka (December 5, 2016). "A Global Estimate of Seafood Consumption by Coastal Indigenous Peoples". PLoS ONE. 11(12).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Haida Nation (2023). "Life begins and ends with the ocean". Haida Nation.

- ↑ GwaaGanad (Diane Brown), Haida HlGaagilda Llnagaay (Skidegate Village) (2023). "Traditional Stories and Creation Stories". Canadian Museum of History.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Government of Canada (2019). "Restricted fishing areas". Government of Canada - Recreational Fishing.

- ↑ Aboriginal Legal Aid in B.C. (August 24, 2023). "Aboriginal harvesting rights". Aboriginal Legal Aid in B.C.

- ↑ Nation, H. v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), 3 SCR 511,(2004 SCC 73).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Davis, John (2010). "MPAs and Indigenous Peoples: Co-Management as a Means of Respecting Traditional Culture and Strengthening Conservation". OCTO: Open Communications for the Ocean.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 22.6 Jones, Russ & Rigg, Catherine & Pinkerton, Evelyn. (2016). Strategies for assertion of conservation and local management rights: A Haida Gwaii herring story. Marine Policy. 80. DOI:10.1016/j.marpol.2016.09.031

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Haida Nation v Canada (March 6, 2015). "Haida Nation v Canada". Indigenous Law Centre.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Council of the Haida Nation (2016). "Press Release: 2016 Commercial Herring Fishery Closed in Haida Waters". Council of the Haida Nation.

- ↑ Parks Canada. "Conservation: Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, National Marine Conservation Area Reserve, and Haida Heritage Site". Parks Canada.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Gwaii Haanas Agreement (1993). "Gwaii Haanas Agreement" (PDF).

- ↑ Coastal First Nations. (2022). Traditional Knowledge. Coastal First Nations. https://coastalfirstnations.ca/our-sea/marine-planning-a-first-nations-approach/traditional-knowledge/

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Natalie C. Ban, Alejandro Frid. (2018). Indigenous peoples' rights and marine protected areas. Marine Policy. Volume 87. Pages 180-185, ISSN 0308-597X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.10.020.

- ↑ Pinkerton, Evelyn; Olsen, Kim; Thorkelson, Joy; Clifton, Henry; Davidson, Art (January 11, 2016). "You Thought We Canadians Controlled Our Fisheries? Think Again". The Tyee.

- ↑ Oregon Public Broadcasting (2021). "Timber Wars". NPR.

- ↑ Eckert, L. E., Ban, N. C., Tallio, S.-C., & Turner, N. (2018). Linking marine conservation and Indigenous cultural revitalization: First Nations free themselves from externally imposed social-ecological traps. Ecology and Society, 23(4). https://www.jstor.org/stable/26796892

- ↑ Simms, R., Harris, L., Joe, N., & Bakker, K. (2016). Navigating the tensions in collaborative watershed governance: Water governance and Indigenous communities in British Columbia, Canada. Geoforum, 73, 6–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.04.005

- ↑ Government of Canada (2023). "Indigenous Guardians". Government of Canada.

This conservation resource was created by Course:FRST522. | |