Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/2023/Carbon credits or carbon piracy? A Case Study of the Kichwa Indigenous People of Ecuador and the Carbon Credits Market

Summary of Case Study

Peru’s Cordillera Azul Park was established in 2001 and is located in the regions of San Martin, Loreto, Huánuco and Ucayali, extending into the Peruvian Amazon[1]. Since 2006, CIMA [decode acronym] has been working to develop a REDD project to ensure long-term funding of critical Park management activities. Between 2008 and 2022, this project traded a total of 30,778,542 carbon credits. The Kichwa Indigenous People of Ecuador, who depend on this forest, have raised protests, asserting that the park is located on their traditional territory and the construction did not go through prior consultation with them[2]. This study analyzes the conflict between Peru’s Cordillera Azul Park and the Kichwa people, including the differences in tenure arrangement, transparency, and indigenous engagement among different stakeholders. The study investigates the negative impact of the REDD+ project on indigenous peoples, thereby striving to identify and propose potential remedial measures.

Keywords

Carbon credits; Credits market; the Kichwa Indigenous People; REDD+ projects

Introduction

[[

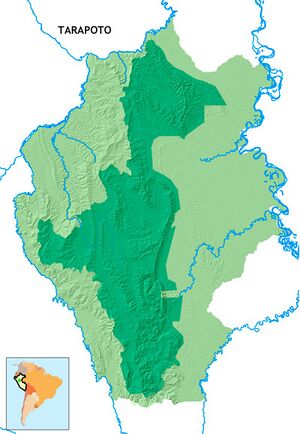

|thumb|Map of the Peru's Cordillera Azul Park]]

Geographic condition, population and history of Peru’s Cordillera Azul National Park

Peru’s Cordillera Azul Park is in the regions of San Martin, Loreto, Huanuco and Ucayali, extending into the Peruvian Amazon, with an ecosystem of tropical forest.[1].It supports rich biodiversity, including over 1000 different vertebrate species and around 6,000 plant species [1] This includes 39 threatened species, including the spectacled bear, jaguar and harpy eagle [3]. Over 250,000 people in 400 communities reside in the buffer zone surrounding the park, and more than 40% live in poverty [4]. The project [which project?] provides technical support for the cultivation of cocoa, coffee and olive oil, which have become the predominant economic activities within this geographical region [5], with 75% of the population declaring this as their main income [6].

In 2001, the establishment of the park ensued after the Field Museum's biological inventory and record of diverse habitat types within the region [7]. This recognition prompted the Peruvian Ministry of Agriculture to advocate for protecting the area as a national park [1]. However, the government was not willing to take the sole responsibility of managing the park. Consequently, a public-private partnership for co-management was instituted, featuring a newly established non-governmental organization (NGO), Centro de Conservación, Investigación y Manejo de Áreas Naturales (CIMA). The collaborative arrangement was formalized through the execution of a 20-year management contract [7].

Since 2006, CIMA has been dedicated to formulating a REDD project aimed at securing sustained funding for essential management activities within the park. This initiative involves collaborative efforts with partners in both Peru and the United States. CIMA focuses on park protection activities and buffer zone activities, strategically aligned to attain the primary goal of forestalling deforestation within the park, generating 25 million carbon credits to date [8].

The culture of the Kichwa Indigenous People of Ecuador

The Kichwa Indigenous People of Ecuador constitute an ethnic group in Peru residing in the vicinity of the town of Lamas, situated in the department of San Martin. These communities form an integral part of the broader Quechua culture and boast distinctive attributes, including their own culture, language, and traditional practices related to forests and agriculture [9].

Kichwa people consider themselves as having a system of preferential relationships that are linked to specific locations, which is named ayllu in the Kichwa language. The ayllu includes both human relatives and the local ecosystem [10]. Now, it has become the highest level of territorial settlement, combining communities, associations, centers and cooperatives [11].

In the context of socio-political organization, the societal framework is delineated by the llackta, serving as the convergence point for individuals, families, and governing authorities [10]. The authorities comprise kuragakuna and yachakkuna. The former is responsible for administering order and justice based on the customary and formal laws of the people, with the primary role falling on the Yachak[10].

In addition, the Kichwa people established an economic system by utilizing natural resources. Agriculture is an important part of the Kichwa people’s economy, with approximately 80% of households involved in the sale of agricultural products in 2000 [12]. Trees and palm trees also provide the Kichwa people with various resources, including timber, medicinal plants, and food [13]. Rather than viewing the forest as a non-human resource, they consider it as a part of their family [14]. For example, the traditional chacra system is a way for the Kichwa people to utilize forest resources sustainably. A chacra is a small planting area, with an area of approximately 0.2 to 4 hectares. By cutting down some of the vegetation in the forest and letting it dry out for several weeks before a contained low-intensity burn, a new chacra can be formed. During the process of clearing the land, some tree and palm tree species are preserved and incorporated into subsequent chacra [13]. More importantly, in the Kichwa people’s economic system, no individual or organization controls the production tools, and the labour is carried out as an informal group[11].

Tenure arrangements

Land ownership

The land ownership status within the Cordillera Azul National Park remains uncertain. According to the validation report for the Cordillera Azul National Park (2013), the park encompasses 1,351,964 hectares owned by the Peruvian national government, with an additional 1,227 hectares located in the northeast section of the park, having been under private ownership prior to the park's establishment. The southeast region of the park is a ‘strict protection zone’ and non-contacted indigenous people from the Cacataibo group live here [8]. In addition, the Peruvian government claims that there are no human activities within the project region [15]. Since Peru signed an International Labour Organization (ILO) convention 169 in 1994, the Peruvian government has been obligated to take necessary measures to identify traditionally occupied land and ensure the effective protection of Indigenous Peoples' ownership [16]. Despite this obligation, the Peruvian government contends that the Cordillera Azul National Park was never traditionally Kichwa land [17]. However, the Kichwa people argued that at least 29 Kichwa communities' lands overlap with the project area [2]. According to an Associated Press investigation, evidence was discovered indicating the prior existence of Kichwa villages within the park, such as a sign displaying the date of construction for a village [17]. Additionally, satellite images show that rainforest clearings for all the villages have the same shapes as today [17]. Therefore, there is a disagreement between the Indigenous Peoples and the national government regarding the ownership of this land.

Management rights

CIMA has a 20-year full management contract with the National Authority for Protected Areas (SERNANP) [3], which is a governing body responsible for the conservation of natural protected areas [18]. CIMA possesses carbon rights throughout the contractual period, with SERNANP retaining overarching authority over the sales of carbon credits [3]. In addition, CIMA claims that Indigenous engagement is an integral part of park management, as demonstrated by the development of Quality of Life Plans involving 35 communities to enhance basic livelihood [3]. However, the dispute over the management rights over the park territory by the Kichwa people remains unresolved. Up to the present, only one Kichwa community (Puerto Franco) has been invited to participate in the park management [2]. Furthermore, the Kichwa people face restrictions on the utilization of forest resources. People who rely on hunting for their livelihoods are now allowed an average of only 300 hunting or fishing activities per year [17]. [Clarify: each hunter or fisher? or the collective community?]

Institutional/Administrative arrangements

Government agencies

The National Forest Park is governed by the Peruvian Forest and Wildlife Protection Law. This legislation categorizes forest resources into two types: national forests and forests of free access [19]. The former can only be utilized by the state for industrial or commercial purposes, while the latter can be freely used by any authorized individual [19]. Authorization is determined by the Ministry of the Environment (MINAM), and to acquire land ownership, the specific purpose of each piece of land (e.g., protected area, agriculture) must be established and authorized [20]. However, the law allows the formal establishment of new land ownership on all lands without formal titles, and some indigenous lands are in the process of formalization without titles, which may result in the dispossession of indigenous lands [20].

In addition, the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation (MIDAGRI) will be responsible for verifying the intended use of forest zones [20]. However, this department is primarily tasked with the development and promotion of agricultural and livestock activities, potentially overlooking biodiversity conservation efforts. The law also categorizes forest protection areas into four types, with the purpose of national parks being the conservation of natural communities of plants and wildlife, as well as attractive landscapes [19].

The Forest Agrarian Promotion and Native Communities Law, enacted in 1974, is a crucial legislation safeguarding the rights of indigenous peoples [19]. According to this law, the state guarantees property ownership for indigenous communities, compiles land ownership registers, issues property deeds, and grants indigenous people the right to develop the forest production potential of their territories as long as they adhere to land use regulations [19]. However, indigenous communities located within national parks can only retain their presence as long as they do not violate the purpose of the national park and do not possess land ownership.

CIMA as the manager of the park

CIMA is the manager of the park, and its establishment is geared towards conservation, research, and livelihood improvement [1]. Since 2006, CIMA has implemented the REDD+ project in Peru's Cordillera Azul Park [1]. This initiative is certified by the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS)[15], and upon certification, these projects are eligible to receive Verified Carbon Units (VCUs), with each VCU representing the reduction or removal of one metric ton of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere [21]. Community meetings and quarterly project reports are the primary means of gathering stakeholder feedback and documenting the plan development process [8]. However, as of now, CIMA does not have a formal written complaints procedure [8].

Affected Stakeholders

The stakeholders affected include the Kichwa Indigenous People of Ecuador, CIMA, and the Peruvian national government, all of whom are entangled in conflicts between land rights and carbon rights.

| Affected stakeholders | Main relevant objectives | Relative power and governance capacity |

|---|---|---|

| The Kichwa Indigenous People of Ecuador | First, the Kichwa people aspire to have their territorial ownership recognized and actively participate in the management of the forest area. Simultaneously, they seek transparency in information regarding CIMA's carbon transactions to ensure the clarity of carbon trading. Additionally, they wish for the exclusion of the Cordillera Azul National Park (PNCAZ) from the Green List as this project infringes upon their rights and does not serve as an exemplary model for environmental protection [2]. | Low. The territorial rights of the Kichwa people have not been recognized, preventing their involvement in park management, and their use of forest resources is restricted. Therefore, they face challenges in exerting influence over this area. |

| CIMA | The purpose of CIMA's establishment is to protect and research the forests and wildlife in this region, assist local communities in improving their standard of living, and ensure a long-term source of funding for the management of the park [1]. | High. CIMA has entered into a 20-year contract (2008-2028) with the Peruvian national government, granting CIMA management rights and carbon rights over this area during this period. Since 2008, CIMA has implemented the REDD+ project, promoting conservation through the sale of carbon credits. Consequently, CIMA wields significant influence over this region [1]. |

| SERNANP | SERNANP has a 20-year agreement with the CIMA, authorizing it as the manager of the park. Additionally, SERNANP and CIMA jointly manage the Cordillera Azul National Park, retaining overarching authority over the sales of carbon credits [3]. | High. SERNANP possesses the authority to determine the management rights of the park [3]. |

Interested Stakeholders

| Interested stakeholders | Main relevant objectives | Relative power and governance capacity |

|---|---|---|

| The Peruvian national government | To protect biodiversity and forest resources and promote the sustainable use of natural resources for economic development, the Cordillera Azul National Park was approved for establishment by the Peruvian national government. Additionally, the ownership of this land is under the authority of the Peruvian national government. | High. The Peruvian government possesses the authority to determine both the ownership and the management of the park. |

| Other institutions and supporting partners such as the United States Agency for International Development, Institute for General Welfare and so on [1]. | Forming a partnership with CIMA, supporting the conservation efforts of the park, and providing financial assistance to the park [1]. | Relative |

| Carbon credits buyers | Purchase carbon credits from CIMA to achieve the company's environmental goals. | Relative |

Discussion

The main conflicts between the Kichwa Indigenous People of Ecuador and the Cordillera Azul National Park project revolve around tenure arrangement, transparency, and Indigenous engagement.

First, regarding the tenure arrangement, the park covers an area of 1,351,964 hectares that the Peruvian national government owns. After deciding to establish a national forest park to protect this area, the Peruvian government, as the owner, signed a contract with CIMA and granted it management rights [21]. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO) convention 169 signed by the Peruvian government in 1994, they are obligated to identify traditionally occupied lands and ensure effective protection of the ownership rights of indigenous peoples [16]. Prior consultation should also take place when establishing the park. However, the Peruvian government and CIMA argue that there has never been community activity in the park area, so the park management does not require the consent of the Kichwa people [17]. Nevertheless, the Kichwa people consider the area where the park was established as their ancestral land [2]. According to an investigation by the Associated Press, much evidence suggests that this is indeed the ancestral land of the Kichwa people. For example, satellite images from before the park was built show that the shapes of open tropical rainforest spaces in all villages are almost the same as today [17].

Furthermore, there is a conflict concerning the level of disclosure of carbon trading information. In 2021, CIMA sold $84.7 million worth of carbon credits to the French company Total Nature Based Solutions (Total NBS) [2]. However, when the Kichwa people requested the responsible agency to provide complete information on the carbon agreement, the institution refused to disclose it [2]. Additionally, the PNCAZ REDD+ Project [decode reference] currently lacks an official carbon counting system and an official buyer list, placing carbon trading in an unregulated gray area [2]. Furthermore, as of now, the most recent project report provided by CIMA dates back to the year 2013, underscoring a notable delay in the disclosure of project management information.

Finally, there is a conflict related to Indigenous engagement. CIMA claims to support 35 local communities through the Quality of Life project, enhancing their access to basic services and promoting sustainable economic development [3]. However, the Kichwa people experience a decline in their quality of life due to CIMA's management. They are restricted in the use of forest resources, such as limitations imposed on hunting or fishing by forest management, thereby depriving the Kichwa people of vital sources of sustenance [17]. Furthermore, the Kichwa people are excluded from the management structure of the park. As of 2021, only one Kichwa community (Puerto Franco) has been invited to participate. Importantly, the establishment of the park did not involve prior consultation with the Kichwa people, and they have not benefited from the carbon credit sales of the park [2].

Critical Issues

This case illustrates the potential adverse impacts of REDD+ projects on Indigenous Peoples, including land appropriation and unequal distribution of authorities and resources.

First, in areas where land rights are not clearly defined, REDD+ projects are more likely to result in the expropriation of indigenous lands. Rights and Resources Initiative & McGill University (2021) found that out of the 31 countries examined, only three explicitly acknowledge the rights of communities to carbon on lands owned by them or designated for community use [22]. In the process of implementing REDD+ projects, changes in the leadership responsible for managing forest areas alter policies and allocations related to land ownership [23]. This creates misunderstandings, making it challenging for community members to ascertain land ownership and confusing the roles and responsibilities of different government agencies in the enforcement process. Additionally, the implementation of REDD+ projects imposes restrictions on the utilization of forest resources in the designated areas, increasing the likelihood of indigenous peoples being deprived of their rights to access their traditional lands and losing vital resources for their survival. Moreover, the financial incentives provided by REDD+ projects may attract investors seeking potential benefits from carbon credits or other advantages, potentially leading to large-scale land grabs and the dispossession of Indigenous Peoples' lands.

The REDD+ project may exacerbate the inequality in authorities and resource allocation, thereby harming the livelihood of Indigenous People. A significant proportion of the lands designated for greenhouse gas (GHG) mitigation actions coincides with areas traditionally under the custodianship of Indigenous Peoples, local communities, and Afro-descendant groups [22]. However, nearly fifty percent of community-held territories lack legal recognition, and even in instances where land rights have been acknowledged, the rights to carbon and tradable emission reductions are rarely clearly defined [22]. The lack of a legal framework makes carbon trading a gray area, and Indigenous People are likely to be unable to benefit from the REDD+ project and suffer losses. Meanwhile, investors face uncertainties regarding the veracity of carbon credits' efficacy in offsetting emissions and achieving stipulated environmental conservation objectives.

Furthermore, the REDD+ project may exacerbate elite capture within communities, leading to an intensification of wealth and resource inequality. Elite capture refers to the control and dominance exercised by a small group of elites in decision-making realms or the monopolization of public benefits and resources by elites [24]. In certain rural areas, the village authority may serve as the sole conduit for communication between the village and the external world, wielding decision-making power and complete control over the utilization of village resources [25]. Research findings indicate that wealthier individuals disproportionately enjoy a larger portion of the overall forest benefits allocated to each village [25]. While REDD+ projects often bring economic incentives to communities, aiming to foster local sustainable development, individuals with greater wealth or power may capture all financial benefits due to their enhanced capacity for utilizing forest resources. Consequently, less affluent individuals may be unable to reap the advantages of these incentive measures.

Recommendations

The REDD+ project aims to reduce carbon emissions, promote forest restoration, protect carbon stocks, improve Indigenous engagement, and preserve biodiversity [26]. However, it may bring negative impacts to Indigenous Peoples, including land grabs and uneven authorities and resource distribution, undermining its intended role in fostering sustainable development. To mitigate these adverse effects, it is essential to clarify land ownership and establish a formal legal framework to regulate carbon trading.

First, the clarity of land tenure is crucial for the success of the REDD+ project. Clearly defining land ownership ensures that communities become equal stakeholders, avoiding conflicts over land tenure between new governance entities and existing communities. This clarification also prioritizes the livelihoods and interests of local communities, emphasizing that the REDD+ project should not forcefully deprive existing communities of their rights under the guise of emission reduction, restricting their access to local forests [23].

Secondly, a comprehensive legal framework is crucial for planning REDD+ projects. Without a well-defined legal framework, the ambiguity surrounding carbon trading rights and land ownership may result in unregulated carbon trading. This makes it difficult to determine whether carbon trading genuinely achieves sustainable development goals or if it merely serves as a means for investors to enhance their reputation. Additionally, existing measures such as Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) have limited effectiveness [23], as the pre-consultation and subsequent information disclosure by REDD+ projects lack proper regulation, exacerbating their negative impacts. Therefore, establishing a legal framework to govern carbon trading is imperative.

This conservation resource was created by Course:FRST522. | |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Centro De Conservation, Investigation Y Manejo De Areas Naturales. (n.d.). Cordillera azul national park. CIMA. https://www.cima.org.pe/en/cordillera-azul-national-park

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 The Ethnic Council of the Kichwa Peoples of the Amazon (CEPKA), the Federation of Indigenous Kichwa Peoples of Chazuta (FEPIKECHA), the Federation of Indigenous Kichwa Peoples of the Lower Huallaga of the San Martin Region (FEPIKBHSAM), & organizations of the Kichwa people in the San Martin region of Peru. (2022). The Kichwa people reject the Cordillera Azul National Park’s exclusionary conservation and opaque carbon trading. Forest Peoples Programme. https://www.forestpeoples.org/en/news-article/2022/Kichwa-peoples-statement-stop-carbon-dealing-our-territories

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Ecosphere. (n.d.). Cordillera Azul National Park Project: Transforming communities, forest and land-use in Peru. Ecosphere. https://ecosphere.plus

- ↑ Initiative 20X20. (n.d.). Building agroforestry systems around Cordillera Azul National Park. Initiative 20X20. https://initiative20x20.org/restoration-projects/building-agroforestry-systems-around-cordillera-azul-national-park.

- ↑ Stand for trees. (n.d.). Cordillera Azul. Stand for Trees. https://standfortrees.org/protect-a-forest/cordillera-azul/

- ↑ Maldonado-Erazo, C.(2022, January 10). Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage: The Amazonian Kichwa People. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18005

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Wali, A. (2016). Chapter 3: Contextualizing the collection: Environmental conservation and quality of life in the buffer zone of the Cordillera Azul National Park. Fieldiana. Anthropology, 45, 21–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44744608.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Scheyvens, H., Gilby, S., Yamanoshita, M., Fujisaki, T., & Kawasaki, J. (2014). Cordillera Azul National Park REDD Project. In snapshots of selected REDD+ project designs – 2013 (pp. 69-80). Institute for Global Environmental Strategies. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep00819.19

- ↑ Caradonna, J. L., & Apffel-Marglin, F. (n.d.). The regenerated chacra of the Kichwa-Lamistas: An alternative to permaculture? AlterNative: An international journal of Indigenous Peoples, 14(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180117740708

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Swanson, T. D., & Reddekop, J. (2022). Feeling with the Land: Llakichina and the Emotional Life of Relatedness in Amazonian Kichwa Thinking. Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 90(4), 954–972. https://doi.org/10.1093/jaarel/lfad032

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Maldonado-Erazo, C. P., Tierra-Tierra, N. P., De La Cruz Del Río‐Rama, M., & Álvarez‐García, J. (2021). Safeguarding intangible cultural heritage: the Amazonian Kichwa People. Land, 10(12), 1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10121395

- ↑ Holt, F. L., Bilsborrow, R. E., & Oña, A. I. (2004). Demography, household economics, and land and resource use of five indigenous populations in the Northern Ecuadorian Amazon: A summary of ethnographic research. Occasional Paper, Carolina Population Center. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina, 87.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Lage, R. D. B. Z., Peña‐Claros, M., & Ríos, M. (2022). Management of trees and palms in Swidden Fallows by the Kichwa people in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4220635

- ↑ Wood, S. (2013). Fair trade and Indigenous Peoples: A case study of the Kichwa in Ecuador. Retrieved from http://purl.flvc.org/fsu/fd/FSU_migr_uhm-0202

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Verified carbon standard. (2013). Validation report for the Cordillera Azul National Park REDD project. https://www.teamclimate.com/assets/pdfs/Peru_3_Validation_Report.pdf

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Swepston, L. (2015). Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 (No. 169). In Brill | Nijhoff eBooks (pp. 343–358). https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004289062_010

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 Davey, E. (2022). In Peru, Kichwa tribe wants compensation for carbon credits. Apnews. https://apnews.com/article/business-peru-forests-climate-and-environment-2c6cddb1707a12c31c14d9a226699068

- ↑ Información institucional. (n.d.). Servicio Nacional De Áreas Naturales Protegidas Por El Estado - Plataforma Del Estado Peruano. https://www.gob.pe/institucion/sernanp/institucional

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 Organization of American States. (1985). Minimum Conflict: Guidelines for Planning the Use of American Humid Tropic Environments. https://www.oas.org/dsd/publications/Unit/oea37e/begin.htm#Contents

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 EnvolVert. (2021). Peru’s Battle for Amazonian Forests: Controversial Law Amendment Threatens Environmental Protection. https://envol-vert.org/en/news/2023/06/perus-battle-for-amazonian-forests-controversial-law-amendment-threatens-environmental-protection/#

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Verra. (n.d.). Verified carbon standard. https://verra.org/programs/verified-carbon-standard/

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Rights and Resources Initiative & McGill University. (2021). Status of legal recognition of Indigenous Peoples’, local communities’ and afro-descendant peoples’ rights to carbon stored in tropical lands and forests. Rights and Resources. https://rightsandresources.org/publication/carbon-rights-technical-report/

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Alusiola, R. A., Schilling, J., & Klär, P. (2021). REDD+ conflict: Understanding the pathways between forest projects and social conflict. Forests, 12(6), 748. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12060748

- ↑ Lund, J. F., & Saito-Jensen, M. (2013). Revisiting the issue of elite capture of participatory initiatives. World Development, 46, 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.01.028

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Andersson, K., Smith, S. M., Alston, L. J., Duchelle, A., Mwangi, E., Larson, A. M., De Sassi, C., Sills, E. O., Sunderlin, W., & Wong, G. (2018). Wealth and the distribution of benefits from tropical forests: Implications for REDD+. Land Use Policy, 72, 510–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.01.012

- ↑ United Nations. (n.d.). What is REDD+? United Nations Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/topics/land-use/workstreams/redd/what-is-redd?gclid=