Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/2023/Agroforestry and Land Sovereignty in Nisg̱a’a Communities of the Nass River Valley in British Columbia, Canada

Summary

The Nass River Valley is situated in the northwestern corner of British Columbia (BC) near the Alaska Panhandle and is home to Nisg̱a’a First Nation.[1] Naturally rich in fish, timber, and minerals, this Valley marks the site of BC's first modern-day land treaty which afforded the Nisg̱a’a people self-governance and land sovereignty over 1990 square kilometers of land and staple food crops. Oolichan and Salmon are fish species that are important in food and ceremonial contexts. Cedar trees are also culturally important.. Today, Nisg̱a’a Nation is headed by the Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government (NLG) which is attempting to return current natural resource management practices back to their traditional Indigenous ways. However, economic pressures combined with non-diversified income streams have made this system vulnerable to the very management styles which had historically suppressed Indigenous resource management in the region. [2] It is imperative that opportunities for joint natural resource management ventures between the Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government (NLG) and Provincial as well as Federal Government are increasingly explored to help expand and secure Nisg̱a’a self-governance throughout the Nass River Valley.[3]

Search terms:

- Nisg̱a’a /ˈnɪsɡɑː/ (Niska)

- Nisga'a

- Nishga

- Nisgat

- Niska

Keywords

Nisg̱a’a First Nation, Agroforestry, Land Sovereignty, BC’s First Modern-Day Treaty, Natural Resource Co-management

Positionality Statement

Before delving further into this case study, I would like to first begin with a reflection on my positionality. Although I am currently enrolled in the Transatlantic Forestry Masters Program (transfor-m) at the University of British Columbia, my presence on these unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) peoples in BC has been one of a traveller who too originates from lands seeped in the bloodshed of broken promises and systemic oppression.

I come from a family of travelers: my father is Indigenous Amazigh (تَمَزِيغت ) from Tunisia, North Africa and my mother was born near Charlemagne's Cathedral in Aachen, Germany. As a first-generation US citizen, my transient roots pushed me to think more deeply about place. I owe much of my interests in stewardship to early education at the Waldorf School where I first learned to acknowledge the traditional keepers of the land with grace and humility. There I also learned about the traditional stewards of Pennsylvania, US, my home state where Lenape, Susquehannock, Shawnee, and Iroquois people first lived.

These reflections do not afford me the right to talk with authority on these topics, nor do they allow me the responsibility to make any assumptions on behalf of Nisg̱a’a First Nation. However, Indigenous and marginalized communities across the globe often carry the weight of systemic oppression, carry similar stories of being silenced, and struggle to reassert their cultural identity within modern-day land stewardship and management practices. It is thus imperative that we leverage the voices of these communities and support them as they fight to regain agency of their land under protection of codified law.

Background and History of Nisg̱a’a First Nation

Historical Land Sovereignty

The Nass River Valley provided the fur, food, tools, plants, medicine, timber, and fuel that formed the initial bedrock upon which Nisg̱a’a First Nation's civilization was founded. [4] This homeland stretches 26,838 square kilometers and allowed Nisg̱a’a People to settle and trade with other communities along all 380 kilometers of river corridors and tributaries within their territory stretching from the glacier-fed lakes of the Skeena Mountains in the northeast all the way to the BC coast. [5]

Social Dynamics of the Nisg̱a’a People

Nisg̱a’a First Nation are comprised of 4 clans: Gisk’aast (Raven/Frog), Laxgibuu (Wolf/Bear), Ganada (Killer Whale/Owl), and Laxsgiik (Eagle/Beaver).[4] Each individual in this community knows their exact duties, obligations, and history within the Nation. [6] Lineages are traced matrilineally and when a child is born their family ties lie with their mother. For example, if the child's mother is an Eagle, her child is also an Eagle. Furthermore, identity questions are not a part of Nisg̱a’a society. All members of this community undergo identity ritualization through "ceremonies at birth, initiation, naming, matrimony, feasting, dancing, funerals, and all other social occasions, all have their object, in some way, the identification of the individual with 'wilp' house and “pdeeḵ” (tribe)". [6]

“1: The Nisg̱a’a Individual is a member of 2. his/her immediate family (ie. mother, father, sisters, brothers). The mother and children belong to one “wilp” (house) while the father is a member of another 'wilp'. 3. The 'wilp' is all blood relatives on the mother’s side. Each 'wilp' shares some common heritage with the other “huwilp” and these “huwilp” compose the “pdeeḵ”. 4. The “pdeeḵ”. -In the Nass Valley, at the present time, there are four “pdeeḵ”. These collectively, make the: 5. Nisgha Nation (The “pdeeḵ” extends to the other nations)". [6]

Nisg̱a’a First Nation Tenure Arrangements

BC's First Modern-Land Treaty

The historical frameworks behind BC’s modern-day land treaty process inform current relationships between the BC government and First Nation communities regarding land self-governance and land-sharing practices across the province. Concepts behind “aboriginal rights and title [are derived] from the common law system [and] the very terms 'aboriginal rights’ and aboriginal title’ have meaning in Canadian legal jurisprudence, [however] these definitions continue to be refined through case law”. [7]Since large parts of BC were not covered by these historic treaties, the province remains primarily unceded territory. [8] Importantly, First Nations in BC “have always maintained that they retained aboriginal rights and title to their land. [7] [9] Treaty-making was then outlawed by the federal Indian Act between 1927 and 1951, with the Canadian government virtually “abandoning” treaty-making in the early twentieth century. Additionally, under “Canada’s constitution, ‘Indians and Lands reserved for the Indians’ are a matter of exclusive federal legislative jurisdiction”. [9] Thus, when BC joined the confederation in 1871, it had to accede to this federally mandated jurisdiction.

In the landmark decision of Calder v. Attorney-General of British Columbia, [1973] S.C.R. 313, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that Nisg̱a’a First Nation had previously held ‘aboriginal’ title to its land pre-contact with the Crown. [10] [11] This landmark ruling was galvanized by Frank Calder who was the Chief of Nisg̱a’a First Nation at the time and “the first native to be elected to the BC Provincial Legislature” after BC’s government granted “Indian people a right to vote in provincial elections”. [12] However, the Court remained “inconclusive as to the continued existence of that title” and so Canada’s comprehensive claims policy was initiated as well as treaty negotiations with the Nisg̱a’a First Nation. [7] [13]

These negotiations, in which BC chose not to contribute, continued for over twenty years before the landmark Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, [1997] 3 S.C.R. 1010 ruling which established groundwork for a modern-land treaty process in BC.

In 2000, the ratification of BC’s first modern-land treaty marked the culmination of over one hundred years of Nisg̱a’a First Nation petitions, litigations, and negotiations at both the federal and provincial level regarding the recognition of their rights and title to the Nass River Valley. [13] [14] The Nisg̱a’a government was given title to over 1990 square kilometers of land and self-governance over laws associated with language revisions, taxation parameters, and traditional customary rights across the four villages that comprise Nisg̱a’a Nation: Gitlaxtʼaamiks, Gitwinksihlkw, Lax̱g̱altsʼap, and Ging̱olx. [15] This ownership of lands included both “surface and subsurface rights (e.g., forest and mineral resources). The Nisg̱a’a government [was given] fishing rights including over approximately 18% of the Nass River Salmon catch which will be managed jointly with the general and provincial Fisheries Authorities as well as self-governance over forest resources and forest management. [12]

Nisg̱a’a First Nation Land Sovereignty

Traditional Agroforestry Practices

Agroforestry is defined as a combination of agriculture and forestry practices to promote food security and land sovereignty. [16] This intentional integration of trees into animal and agricultural systems has significant environmental, cultural, and economic implications for increasing market diversification and future system resilience.

Over 200 years ago a devastating volcano erupted in the Nass River Valley and killed thousands of Nisg̱a’a People.[1] These ancient lava beds are sacred burial grounds for the Nisg̱a’a People and inform agroforestry practices throughout this region.[1] Volcanic deposits, rich in magnesium and potassium, have provided nutrients to all natural resource sectors in the Nass River Valley: from critical watersheds to forest ecosystems.

While a myriad of benefits and Non-timber Forest Products (NTFPs) have been derived from this region for thousands of years—current research suggests that Salmon, Oolichan, and Western Red Cedar (Thuja plicata) represent the three predominant agroforestry hallmarks of the Nisg̱a’a People.

Salmon

According to the tradition of Wiihoon (Large-Salmon), a Chief among the Nisgha in 1929 proclaimed that the Ḵ’amligihahlihaahl (Supreme Being) sent the lava flows to punish the people for making fun of the salmon”. [17] Each season 5 major salmon species return to the Nass River Valley: Pink (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha), Sockeye (Oncorhynchus nerka), Chum (Oncorhynchus keta), Chinook (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), and Coho (Oncorhynchus kisutch). [18] Mid to late spring brings snow melt and salmon runs. Salmon were "netted, harpooned, or trapped [by the Nisg̱a’a People], but the majority spawned and died". [18][17] Salmon are carefully smoked and rationed to provide a critical food source throughout the winter months. [1]

Oolichan or "Saak"

Oolichan signal the arrival of Nisga’a new year (Hoobiyee) and celebrations take place across all 4 villages. Oolichan (Thaleichthys pacificus), traditionally called "Saak," represent the most important food staple for the Nisg̱a’a People. These fish were termed 'savior fish' as they arrived just as salmon winter reserves were beginning to run out. Oolichan are caught using 'neck-poles' [1] and cured outside for grease making or hung up in smokehouses for food. After Oolichan harvests are sufficiently cured outside they are rendered into grease and tipped into boil room tanks where the mixtures are stirred to separate oils from the fish. [1]

The frozen Nass River was historically used as an important trade route and 'highway'. [3] Climate change has made fishing Saak much more harrowing as the rivers no longer freeze and one has to fish from boats rather than dig holes through the ice. Likewise, spawning areas are moving downriver closer to the coast. [3]

Western Red Cedar

Western Red Cedar (Thuja plicata) was most often used for carving totem poles, canoes, masks, longhouses, bark for weaving, and smokehouses.[19] Due to this pervasive use throughout Nisga’a society, Cedar was often traditionally referred to as simgan which translates to the sacred tree and "they said when the creator was designing the valley for us, the first tree he planted was cedar, because he knew that we will depend on it so much. [19] Culturally modified cedars were also an integral part of Nisga’a First Nation's treaty negotiations as they were used to "prove that they had been living [on] the land they were claiming far before European colonization. [19]

Medicinal Forage

There are 7 plant species which hold traditional importance in Nisga’a culture: “Shepherdia canadensis (soapberry), Vaccinium membranaceum (black huckleberry), Oplopanax horridus (devil’s club), Corylus cornuta (beaked hazelnut), Malus fusca (Pacific crabapple), Veratrum viride (false hellebore), and Taxus brevifolia (western yew)”. [15] For example, Devil's club stems were "measured in clearcuts of different ages to examine how quickly this important spiritual and medicinal species recovers after logging". [15] Excerpts like these are numerous throughout the Nisga’a literature and describe relations between the clear-cut logging practices which dominating the Valley for decades and Indigenous forest management of the land.

Affected Stakeholders and Trade Routes

The Nisga’a People had highly complex trade routes throughout their vast territory and their modern-land afforded them "wide control over resources in an extensive area of the upper Nass River drainage [which overlaps the claim areas of the Gitanyow and the Gitksan and has been contested by both groups and ownership of the core of their homeland in the lower Nass valley”. [15] The Gitskan People, a critical trade partner with the Nisga’a People, [18] is currently bidding to control their lands and waters (with extensive forestry, fisheries, and mineral resources) through a cooperative management context with the British Columbia provincial government and the government of Canada. Gitskan's landmark land claims court case (Degamuukw v. the Queen) was decided in their favor on appeal to the Canadian Supreme Court in December 1997”. [15] The Nisga’a People also supplied fish, particularly Oolichan and fish oil, across the region and these routes were termed “grease trails”. [20]

Continued degradation of social capital due to resource conflicts between these neighboring groups, combined with climate impacts on natural resource management, has placed increasing strains on land sovereignty and the future resilience of these communities.

Parallel Case Study Analysis: Critical Issues in Current Indigenous BC Legislature

A Brief Overview of Specific Claims in Canada

Similarly to BC's modern-land treaties, specific claims were designed to resolve unkept promises within historic treaties, the federal Indian Act, other negotiations between the Federal government, province, and First Nations. [21] In 1927, the Canadian parliament passed a series of amendments to the 1876 Indian Act with the intention of repressing Indigenous activism across the Nation. These amendments, which persisted in law until 1951, “effectively barred Indigenous people from using the courts to vindicate their rights and force the government to deal with claims”. [22] In response to Calder v. Attorney-General of British Columbia [1973] S.C.R. 313 hearing, the federal government began to negotiate “comprehensive claims” with Indigenous nations and this approach ultimately facilitated the signing of BC’s first modern-day treaty with Nisg̱a’a First Nation.

Barriers to specific claim implementation are also numerous. The process of submitting and drafting specific claims is convoluted, expensive, and resource intensive for Indigenous communities. First, all documents and supporting legal drafts must be submitted to the Specific Claims Branch (SCB). The Department of Justice then decides whether or not to pursue this claim and, importantly, if the specific claim is declared unfounded the SCB rejects the claim and this decision cannot be appealed. In order to continue pursuing this claim, Indigenous communities must resort to judicial review through the courts. [23]

Notably, 90% of the total claims from the backlog generated between 2008 and 2011 were marked as ‘resolved’ by SCB rejection or file closure “which occurs when a First Nation declines the Crown’s offer to settle”. [21] The remaining 10% were ‘resolved’ through ‘administrative remedy’ or ‘through actual settlement’. In tandem, these syntax details paint the illusion that both the SCB and “Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development are making ‘substantive progress in resolving claims and clearing up its claims backlog,’ when in fact, it is merely shifting responsibility for the logjam onto the tribunal”. [21]

It is only in the past forty-five years that Indigenous peoples have been afforded greater representation and self-governance in the forestry and natural resource sector through landmark cases and revisions in governmental policy.

While this study focuses on Nisg̱a’a First Nation which received BC's first modern-land treaty and was asserted governance rights over their land under constitutional protection—few Indigenous communities have been afforded this removal of Federal Indian Act jurisdiction. One such example is Nlaka’pamux First Nation. This community is situated in the Fraser River Valley of BC and is currently embroiled in numerous lawsuits around the devastating Lytton fire of 2021 which may have been catalyzed by historic fire suppression of cultural burning practices in the area and the Canadian National Railway (CN). [24]

The town of Lytton lies at the confluence of the Fraser and Thompson rivers.

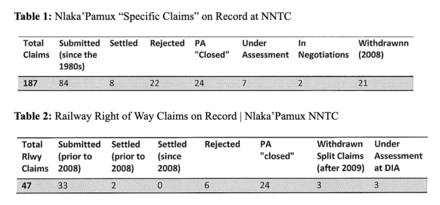

Archeological evidence of fire use in the region by Nlaka’pamux First Nation dates all the way back to the early Holocene or 8000-7500 BCE Fire became a tool to increase foodstuffs or edible plant availability for these people, maximized agricultural yield, and ultimately ensured greater food security for generations to come. [25] Spring burns aimed at increasing wild celery, pine mushroom, oval-leaf blueberry, red huckleberry, garden asparagus, indian potato, and grayleaf red raspberry while frequent fires helped support bunchgrass ecosystems and controlled ponderosa pine growth. [25] While cultural burning in and around Lytton has been implemented as a land management tool for over 7000 years, European settlement in the Fraser valley effectively erased Indigenous fire use from the landscape. Additionally, large-scale variable intensity burns that had become common practice for thousands of years were no longer permitted by the mid-century. Historic fire suppression in and around Lytton meant a fundamental shift in vegetation. Former bunchgrass grasslands, which were critical sources of edible plants and food gardens for the Nlaka’pamux, have largely been replaced by ponderosa pine and sagebrush encroachment. Additionally, lack of ponderosa pine stand management has made them more susceptible to forest pathogens, particularly mountain pine beetle, and catastrophic fire. Today, Nlaka’pamux–unlike Nisg̱a’a First Nation–have not been granted self-governance over their traditional land and forest resources. Not only has historic suppression of cultural burning practices made the land increasingly more susceptible to catastrophic fires, but specific claims particularly with the CN railway have compounded these impacts (see Table 1, 2).

In 2017 Nlaka’Pamux Nation Tribal Council (NNTC) submitted a report on the Standing Committee 2017 Study on Comprehensive and Specific Claims. The opening lines of this report state that, “for the NNTC, the BC Treaty process is untenable as it is inconsistent with our title and rights. We will not participate in that process and believe there must be respectful, viable alternatives. Our focus, however, in our presentation and submission to the Committee is on the Specific Claims Program, recognizing though, that there is an artificial distinction between comprehensive and specific claims”. [26]

The Nlaka’Pamux First Nation has been involved in specific land claims since 1985 and stopped the Canadian National railway (CN) from constructing a second track through their land which would have detrimentally impacted their title and rights (Nlaka’pamux Nation Tribal Council, 2017). The CN railway cuts across 79 Nlaka’pamux reserves (see Table 2).

While thirty-three claims were submitted prior to 2008, only two were negotiated and settled (one in 1997 and one in 2007). The NNTC report then continues by stating that no claims have been settled since Justice At Last: a specific claims action plan passed in 2007 to help return Justice to the claim application process. Further, twenty-four claims were left with take-it or leave-it offers and were subsequently closed. The report states, “These numbers hint at what Canada's relationship with the Nlaka’pamux has amounted to over the last 30 years. Our chiefs have requested negotiations and meetings; we have invited Government officials to visit the territory and see for themselves where we live and how the takings in the transportation corridor continue to impact our communities. And Chiefs have been met with silence on the one hand, and refusal on the other. Minister Crombie’s commitment to resolving Nlaka’pamux claims in an expedited manner has amounted to the resolution of two claims in thirty-three years”. [23]

Governmental negligence, combined with cultural fire suppression, and the degradation of Nlaka’pamux homeland may have helped catalyze the role of CN railway in initiating the catastrophic 2021 fire in Lytton, BC. To counter this, Indigenous communities must demand a reimagining of current modern-treaties to include greater self-governance with detailed, actionable rights. Specific claims can no longer be a viable option in isolation, but must only be used in tandem with revised and amended modern-day treaties in order to foster greater co-management and land-sharing between First Nations and the Government.

Results from this preliminary analysis demonstrate that in contrast to Nisg̱a’a First Nation, Nlaka’pamux First Nation’s sole focus on specific claims rather than BC's modern-land treaties has meant that their fight for self-governance has been disproportionately undermined by specific claim negligence throughout the claim process, especially pertaining to CN railway.This Government negligence, combined with cultural fire suppression, and the degradation of Nlaka’pamux homeland may have helped catalyze the role of CN railway in initiating the catastrophic 2021 fire in Lytton, BC. To counter this, Indigenous communities must demand a reimagining of current modern-treaties to include greater self-governance with detailed, actionable rights. Specific claims can no longer be a viable option in isolation, but must only be used in tandem with revised and amended modern-land treaties in order to foster greater co-management and land-sharing between First Nations and the Government.

The Impacts of the Nisg̱a’a First Nation’s Modern-Day Treaty on Land Sovereignty

The Delgamuukw v. British Columbia (1997) supreme court case demonstrated that First Nations have rights to the land itself and not just rights to hunt, fish, and gather, and that Aboriginal title has not been extinguished.

Commercial logging by non-Indigenous forest companies came to a halt when BC’s first modern-day land treaty was passed in 2000. Not only did this treaty afford the Nisg̱a’a decision-making authority and forest governance, but it also legally recognized over 1990 square kilometers as Nisg̱a’a land. [27]

Without this treaty, agreements like the co-managed Nisg̱a’a Memorial Lava Bed Park or Anhluut’ukwsim Laxmihl Angwinga’asanskwhl and first provincial park to be jointly managed by the Provincial Government and a First Nation would not be feasible. [28]

In BC, NTFPs from wild harvesting to agroforestry have become an increasingly marketable way for community forests and joint forestry ventures to diversify their income streams amidst fluctuating markets. [29] Nisg̱a’a First Nation who obtained clear title to this land as a result of their treaty settlement, manage a significant portion of private land throughout the Nass River Valley. The vast extent of public land ownership in BC means that issues relevant to NTFP management are significantly affected by provincial government decisions. [27]

Today, Nisg̱a’a Nation is headed by the Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government or NLG which is attempting to return current forestry practices back to their traditional Indigenous ways by using smaller cut-block sizes, however, economic pressures combined with non-diversified income streams have made this system revert to clear-cutting forestry as the dominant management style. [30]

A Reimagining of Nisg̱a’a First Nation’s Modern-Land Treaty

The Nass River Valley, home to Nisg̱a’a First Nation, is rich with natural resources and thus has faced numerous economic pressures to increase resource extraction and development. The widespread use of cut and run logging throughout the Nass in the early and mid-20th century had quickly transformed these rich forest systems into degraded fire and disease prone stands. [27] However, commercial logging by non-Indigenous forest companies came to a halt when BC’s first modern-day land treaty was passed in 2000. Not only did this treaty afford the Nisg̱a’a decision-making authority and forest governance, but it also legally recognized over 1990 square kilometers as Nisg̱a’a land. Today, Nisg̱a’a First Nation is headed by the Nisga’a Lisims Government or NLG which is attempting to return current forestry practices back to their traditional Indigenous ways by using smaller cut-block sizes, however, economic pressures combined with non-diversified income streams have made this system revert to clear-cutting forestry as the dominant management style. [27]

Thus, while Nisg̱a’a First Nation was afforded greater self-governance than Nlaka’pamux due in part to the BC’s first modern-land treaty, Nisg̱a’a First Nation still has numerous economic pressures threatening traditional and cultural practices on the land. However, these challenges also present great opportunities for co-management and land-sharing opportunities between the Government and Nisg̱a’a First Nation. Due to Nisg̱a’as’ modern-land treaty all federal and provincial laws (e.g., wildlife laws) now apply across Nisg̱a’a territory. [14] These opportunities for co-management combined with treaty-protected self-governance have allowed the Nisg̱a’a people to successfully petition for the transition of Oolichan, one of their staple food sources, from being listed as an endangered species to one of special concern by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). Furthermore, in 2016 the Coast Conservation Endowment Fund approved $91,000 toward the Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government for Oolichan spawning stock biomass research. Additionally, 18% of the Nass River Salmon catch was allocated for joint management between the general and provincial Fisheries Authorities and the successful reassessment. [31]

In summation, while Nisg̱a’a First Nation had numerous setbacks during their modern treaty negotiation process and ultimately had to settle for less land and governance capacity than was initially outlined—active negotiations and joint natural resource research opportunities through these treaty negotiations with Governmental organizations have helped support the Nisg̱a’a economy navigate a myriad of economic pressures that continue to dictate the industrial form of forest management and natural resource extraction. [32] [33]

The Implications of Current BC Legislature on the Future of Indigenous Self-governance and Land Sovereignty

The Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People Act (DRIPA) represented the BC legislature which aimed at integrating the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) into BC legislature.

Canada, which contains almost ten percent of the world’s forests, initially voted against the adoption of UNDRIP, with almost a decade passing before a national commitment was made to “full and effective implementation”. [34]

While the topic of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) is part of UNDRIP, it was not incorporated into BC policy as this would have granted veto power to First Nation communities. The future of land-sharing between Indigenous communities and the Government rests in legislation like Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) and these legislative frameworks represent an essential component of future resource co-management as they codify the right to self-governance of First Nations by protecting their negotiation and participation regarding actions that would directly impact their communities. [35]

Recommendations

| Theme: Indigenous Agroforestry and Land Sovereignty | |

| Country: Canada | |

| Province/Prefecture: British Columbia | |

This conservation resource was created by Sophia BenJeddi. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0. | |

According to [35]: a forest management system truly representative of "Aboriginal forestry' is one in which First Nations hold both permitting and veto authority, traditional knowledge keepers are included in decision-making during consultations, and trained forest practitioners are "equally required to train in aboriginal forest management systems as in non-aboriginal management systems". [34] While the future of land-sharing and joint resource management in Nisg̱a’a First Nation rely on secure BC and Federal legislature like UNDRIP and FPIC to solidify their Bundle of Rights, the current co-management landscape is undergoing rapid shifts, In 2013, over “13% of the provincial Annual Allowable Cut (AAC) [was] held by First Nations, a figure that has increased from under 8% in 2010. [36]

Thus, while numerous economic pressures continue to place limitations around natural resource management in the Nass River Valley, the Nisg̱a’a First Nation's impactful modern-day land treaty fundamentally paved the way for Indigenous self-governance and land sovereignty legislature in BC.

Indigenous communities must continue to demand a reimagining of current modern-treaties to include greater self-governance with detailed, actionable rights. These revised and amended modern-day land treaties have the opportunity to foster greater co-management and land-sharing ventures between First Nations and the Government.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Rosalind, F., & John, B. (2008). Nisga’a Nation Series: Nisga’a Beyond Survival. Common Bowl Productions. (DVD), 18:46/00. Retrieved from XWI7XWA Library: Call Number BDE N57 v.3 2007.

- ↑ Whitney, C., Frid, A., Edgar, B., Walkus, J., Siwallace, P., Siwallace, I. and Ban, IN. 2020. ‘Like the plains people losing the buffalo': perceptions of climate change impacts, fisheries management, and adaptation actions by Indigenous peoples in coastal British Columbia, Canada. Ecology and Society 25(4): 1–17.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Arias-Bustamante, J. (2013). Indigenous knowledge, climate change and forest management: The Nisga'a Nation approach (Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia), 56. doi: 10.14288/1.0166831.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government. (1995). Lock, Stock and Barrel: Nisg̱a’a Ownership Statement. Nisg̱a’a Tribal Council, 5. Retrieved fromhttps://www.nisgaanation.ca/sites/default/files/NLG-LockStockBarrelOnline.pdf.

- ↑ Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government. (1995). The Land and Resources: The Traditional Nisg̱a’a Systems of Land Use and Ownership | Ayuukhl Nisga’a Study. Wil Wilxo’oskwhl Nisg̱a’a Publications, IV. Retrieved from Xwi7xwa Non-circulating Collection: E99.N734 A98.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Nishga Tribal Council. (1994). Nisg̲a'a land question: A generation of Nisg̲a'a men and women has grown old at the negotiating table. Nisg̲a'a Tribal Council, 3.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Hydman, M. (2002). Negotiating space: geographies of the British Columbia treaty process. Bachelor dissertation, University of British Columbia, 21. doi: 10.14288/1.0090730.

- ↑ Nisgha Tribal Council. (1998). Understanding the nisga’a treaty. Retrieved from https://www.nisgaanation.ca/sites/default/files/Understanding%20the%20Nisga%27a%20Treaty%201998.pdf.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Dickson, J. (2018). By law or in justice. the Indian Specific Claims Commission and the struggle for Indigenous justice. Purich Books, 16. Retrieved from https://books-scholarsportal-info.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/uri/ebooks/ebooks3/upress/2018-04-08/1/9780774880077.

- ↑ Asch, M. (1999). “From Calder to Van der Peet: Aboriginal Rights and Canadian Law, 1973-96.

- ↑ Hamar, F.,Raven, H., & Webber, J. (2007). Let Right Be Done: Aboriginal Title, the Calder Case, and the Future of Indigenous Rights. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 “BC to sign historic treaty with nisga'a first nation” (1998). Toronto: CTV Television, Inc. Retrieved from: https://www.proquest.com/other-sources/bc-sign-historic-treaty-with-nisgaa-first-nation/docview/190417013/se-2.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Blackburn, C. R. (2003). Negotiating rights, reconciling history: The Nisga'a treaty and the terms of inclusion in the Canadian state. Stanford University. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/negotiating-rights-reconciling-history-nisgaa/docview/305300633/se-2?accountid=14656.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Blackburn, C. (2021). Beyond Rights: The Nisg̱a’a Final Agreement and the Challenges of Modern Treaty Relationships. UBC Press.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Burton, C.M.A. (2012). Wilaat Hooxhl Nisga’ahl [Galdoo’o] [Ýans]: Gik’uuhl-gi, Guuń-sa ganhl Angoo gam´ Using Plants the Nisga’a Way: Past, Present and Future Use. University of Victoria (Canada), 322. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/wilaat-hooxhl-nisgaahl-galdooo-ýans-gikuuhl-gi/docview/1524965880/se-2?accountid=14656.

- ↑ Sinclair, F. L. (1999). A general classification of agroforestry practice. Agroforestry systems, 46, 161-180.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Nisgha Cultural Infusion Resource School District 92. (1981). Bilingual-Bicultural Department. Lip hli g̲andax̲gathl Nisg̲aʻa: The people of Kʼamligihahlhaahl. School District 92 (Nishga), 13.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Johnson, L. M. (2000). “A place that's good,” Gitksan landscape perception and ethnoecology. Human Ecology, 28, 301-325. doi: 10.1023/A:1007076221799.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Arias-Bustamante, J. (2013). Indigenous knowledge, climate change and forest management: the Nisga'a Nation approach (Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia). doi: 10.14288/1.0166831.

- ↑ Patterson, E. P. (1982). Mission on the nass: The evangelization of the nishga (1860-1890). Eulachon Press, 19.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Dickson, J. (2018). By law or in justice. the Indian Specific Claims Commission and the struggle for Indigenous justice. Purich Books, 13. Retrieved from https://books-scholarsportal-info.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/uri/ebooks/ebooks3/upress/2018-04-08/1/9780774880077.

- ↑ Dickson, J. (2018). By law or in justice. the Indian Specific Claims Commission and the struggle for Indigenous justice. Purich Books, 21. Retrieved from https://books-scholarsportal-info.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/uri/ebooks/ebooks3/upress/2018-04-08/1/9780774880077.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Dickson, J. (2018). By law or in justice. the Indian Specific Claims Commission and the struggle for Indigenous justice. Purich Books, 41. Retrieved from https://books-scholarsportal-info.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/uri/ebooks/ebooks3/upress/2018-04-08/1/9780774880077.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Parsons, K. (2022). Post climate catastrophe and the pursuit of solace. UBC Press. Doi: 10.14288/1.0413685

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Lewis, M., Christianson, A., & Spinks, M. (2018). Return to flame: reasons for burning in Lytton First Nation, British Columbia. Journal of Forestry, 116(2), 143-150.

- ↑ “Nlaka’Pamux Nation Tribal Council Submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affair” (2017). Retrieved from https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/INAN/Brief/BR9193956/br-external/NlakapamuxNationTribalCouncil-e.pdf.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Arias-Bustamante J.R. and Innes J.L. 2021. Adapting forest management to climate change: experiences of the Nisga’a people. International Forestry Review 23(1): 1-15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1505/146554821832140402.

- ↑ Nisga'a Lisims Government. "Lava Bed Park". Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ↑ Hamilton, E. (2012). Non-timber forest products in BC: Policies, practices, opportun. Journal of Ecosystems and Management. 13 (2), 1–24. doi:10.22230/jem.2012v13n2a165.

- ↑ Arias-Bustamante, J. (2013). Indigenous knowledge, climate change and forest management: The Nisga'a Nation approach (Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia). doi: 10.14288/1.0166831.

- ↑ Connauton, J.K. (2023). Reimagining BC Modern Treaties: A Critical Discourse Analysis of the Tsawwassen, Maa-nulth, and Tla’amin Final Agreements. (Masters Dissertation, Royal Roads University). Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/reimagining-bc-modern-treaties-critical-discourse/docview/2820207708/se-2.

- ↑ Matakala, P. W. 1995. Decision-Making and Conflict Resolution in Co-management: Two Cases from Temagami, Northeastern Ontario. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia. doi: 10.14288/1.0088332.

- ↑ Marcella, L. (2008). Communication for Public Decision-Making in a Negative Historical Context: Building Intercultural Relationships in the British Columbia Treaty Process. doi: 10.1080/17513050801891978.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Doyle-Yamaguchi, E. (2021). A predictive modeling and ecocultural study of pine mushrooms (Tricholoma murrillianum) with the Líl̓wat Nation in British Columbia, Canada (Masters dissertation, University of British Columbia). doi: 10.14288/1.0401450.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Wyatt, S. (2008). First Nations, forest lands, and “aboriginal forestry” in Canada: from exclusion to comanagement and beyond. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 38, 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1139/X07-214

- ↑ Lenze, J. (2013). Aboriginal Forestry in British Columbia. doi:10.14288/1.0075563.