Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/2022/Wonolestari Community Forest in Central Java, Indonesia: challenges and opportunities with SVLK certification

Summary of Case Study

Wonolestari Community Forest Management Unit is located in Bantul, Central Java, Indonesia. This Unit was established on July 10, 2012, and registered with a notary in December 2012. It covers a management area of 959,305 hectares and has 3,570 members spread over three villages. To improve its members’ livelihood, Wonolestari continues to develop its business. One of them is participating in the SVLK certification program with financial and technical assistance from the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, ARuPa (NGO), LEI (Indonesian Ecolabelling Institute), and the EU (European Union). In March 2015, Wonolestari received an SVLK certificate with 3,566 families and an area of 957.57 hectares. This case study describes the challenges and potential improvements experienced by Wonolestari in the SVLK certification process. It also looks at the market side of the SVLK-certified product and its impact on business sustainability in the long run.

Keywords

community forestry, SVLK, FLEGT, wood certification, sustainable forest management, Indonesia

Introduction

Wonolestari Community Forest Management Unit (CFMU) is located in Bantul, Central Java, Indonesia. This unit was established on July 10, 2012, and registered with a notary in December 2012. The background to the establishment of the Wonolestari CFMU was the issuance of Minister of Forestry Regulation No. 38 of 2009 (P.38/Menhut-II/2009) concerning standards and guidelines for evaluating the performance of sustainable production forest management and verifying timber legality. This mandatory regulation encourages the owners of community forests to create a legal entity that serves as a forum for all community forest owners in Bantul Regency (Wonolestari Community Forest Management Unit, 2017).

Wonolestari CFMU initial management area is 1027.604 Ha which was located across thirty-four hamlets in Sendangsari Village and Triwidadi Village. Nowadays, it covers a management area of 959,305 hectares and has 3,570 members spread over three villages, with Guwosari Village as the latest additional member.[1] Its members are mostly smallholders that generally grow teak, mahogany, acacia, and fruit trees on their forest land. They usually mixed these trees with agricultural crops, a system that is communly called as "tumpang sari".

Community forestry in Java Island has distinct characteristics that are different from community forestry on other islands in Indonesia. They are generally developed and managed on private land property with less fertile soil, difficult topography, low accessibility, sober maintenance, and a small risk of failure. Thus, the weakness of community forests in Java is the limited and sober silvicultural technique (such as rejuvenation, use of superior seeds, maintenance, and harvesting methods). Community forestry in Java is managed in a traditional/family-based manner and is less intensive. The main utilization of community forests is wood production which serves as long-term savings, only harvested when there is a household financial need.[2]

Though there are several problems associated with smallholders in Java, they actually play a significant role in meeting the demand for timber needed to maintain national forestry industries. In 2019 alone, the total volume of smallholder FMU production was 3,360,565,549 m3. Over the last five years, this number has been steadily increasing at an average rate of 2.84%. Table 1 below shows that the total log produced by smallholders FMU that contributes around 6,012,594.82 m3 comes to second place after state plantations production forest.

Table 1. Five largest national log suppliers in 2018

| No | Source | Supply in 2018 (m3) |

| 1 | State Plantation Production Forest | 40,079,339.02 |

| 2 | Smallholders FMU plantation | 6,012,549.84 |

| 3 | State Natural Production Forest | 4,895,796.66 |

| 4 | Community Forest | 1,328,862.09 |

| 5 | Import | 808,173.62 |

Source: Statistik Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan 2018 (Ministry of Environment and Forestry, 2019)

Smallholder FMU in Java Island has historically been part of a community-based rehabilitation effort by the Government of Indonesia that has been carried out since the reform era in 1998.[3] It is estimated that there are approximately 6.8 to 10.8 million households planting trees in Java alone.[4] Nowadays, community forestry is one of five schemes under social forestry, namely village forests (hutan desa), community forests (hutan kemasyarakatan), community plantation forests (hutan tanaman rakyat), forestry partnerships (kemitraan kehutanan), and customary forests (hutan adat). The social forestry program is the flagship initiative of the Indonesian Government's agrarian reform enacted by President Joko Widodo. This is an effort to ensure the availability of land and forest areas to local and indigenous communities and to achieve social justice in the use of forest areas and resources.[5] The social forestry program has an ambitious target of providing communities with legal access to 12.7 million hectares of state forests, allowing them to manage these resources sustainably for their own livelihoods and for forest protection.[6]

Social Forestry places the community and local culture as an inherent part of forest management. The community is neither outside the arena nor viewed as a disturbance to forest management. Besides the State and the private sector, communities also play an essential role in forest management, including in decision-making. For some experts, Social Forestry is driving devolution in forest management. [7]

Tenure arrangements

In terms of tenure arrangement, approximately 95% land of Wonolestari community forestry is privately owned.[8] This is a very specific case of forest on Java and Madura Island.[2] Thus, the Wonolestari community holds the safest tenure ownership over their forest land because they do not need to face tenurial conflicts. However, the government still gives the “community forestry” status, because they intend to strengthen the legality of timber produced on the private land owned by the community through joint marketing and certification. “Community forestry” status is also expected to strengthen the communal approach which is considered to be able to reduce land sales that lead to land conversion and excessive logging by individual private forest owners.

Although communities have private ownership over the forest land, they cannot freely harvest the trees they planted, especially if they plant high-value species, such as teak. To be able to harvest trees on their land, farmers must apply for permits that require several documents and approval from several village institutions up to the district level which needs a significant amount of formal and informal costs.[9] This administrative burden, combined with the attempt to reduce technical logging risk, is the reason why the logging of trees in community forests in Java is generally not carried out by the owner but handed over to the buyer or logger who has the necessary skills, equipment, and channel to fulfill administrative requirements, even when the wood is used by the farmers family themselves.[2]

Therefore, in terms of the legal bundle of rights, the communities of Wonolestari enjoy access, exclusion, management, alienation, duration, bequeathe, and extinguishability rights. However, they do not have withdrawal/use rights for high-value species such as teak. They still have withdrawal/use rights for other species like agricultural crops.

SVLK Program in Wonolestari

International markets require producers, including smallholders, to verify the legality of their wood products to address the issues of illegal logging and illegal trade. Indonesia, as a timber exporting country with a significant export volume, decided to prepare Timber Legality Verification System (or Sistem Verifikasi Legalitas Kayu-SVLK in Bahasa Indonesia) that covers the upstream and downstream wood industries. The system was meant to ensure all parties in the timber supply chain obtained their wood and timber products from sustainably managed forests and conducted business according to both current laws and regulations. After a long process that involved various relevant stakeholders in the forestry sector since 2003, on June 12, 2009, the Ministry of Forestry issued Minister of Forestry Regulation No. 38 of 2009 (P.38/Menhut-II/2009) concerning standards and guidelines for evaluating the performance of sustainable production forest management and verifying timber legality, that applied to state and private forests. By the end of 2011, the regulation was revised and improved by the issuance of Minister of Forestry Regulation P.68/Menhut-II/2011. The effort was supported by the EU--one of the key markets, with the Netherlands, England, Germany, Belgium, and France as the top five destination countries that absorb Indonesian timber and finished wood products-- and the ITTO--an intergovernmental organization promoting the sustainable management and conservation of tropical forests.

In August 2011, ARuPa (Volunteer Alliance for Nature Conservation)--an NGO working in the field of natural resource and environmental preservation--collaborated with the Ministry of Forestry's Center for Standardization and Environment (PUSTANLING), as well as the Yogyakarta Provincial Forestry and Plantation Service, to facilitate community forestry groups in Triwidadi and Sendangsari village. This support was provided to help community forestry groups obtain certification for sustainable community forest management. As a result, in March 2013 Wonolestari CFMU was granted the SVLK certification with a managed area of 786.54 hectares spread across Sendangsari and Triwidadi Villages. Furthermore, in March 2015, there was a regular SVLK monitoring assessment and Wonolestari CFMU managed to get the SVLK certificate with a new management area of 957.57 hectares.[1]

It is interesting to analyze SVLK intervention which aims to improve the community's livelihood with Scoone's sustainable rural livelihood analysis framework. This framework divides people's assets into five types: human capital, natural capital, physical capital, financial capital, and social capital.[10] The objective is to explore whether the introduction of SVLK was considering each aspect, identifying the gap, and providing targeted interventions.

Human capital

The heart of the intervention is to increase the capacity of communities in managing their community forestry. It is obvious that there is a gap in the community’s capacity in managing their community forestry to meet the technical process required by certification standards.[2] [11] The government in collaboration with the NGO has provided some training to improve the community’s capacity, hence addressing the gap in human capital.

Natural capital

The community’s main asset is natural capital. It is the total forest area that is managed by Wonolestari CFMU. However, given the limited area of forestry land in Java,[2] the natural asset is not adequate to secure the continuous timber supply required by international buyers. Apart from that, there is also a threat of land conversion, because many developers are interested in this area to develop housing complexes.[12] To address these challenges, ARuPa collaborated with the Indonesian Ecolabelling Institute (LEI) with funding from the European Union (EU), to implement “Scaling Up Legality Verified Community Forest and Small and Medium Wood Industries to Increase Supply for FLEGT Licensed Timber and Timber Products” program, which started on April 2014. In this intervention, capacity-building activities were focused on Guwosari Village which is a neighboring village to Sendangsari and Triwidadi. Furthermore, on October 1, 2014, the community forestry group in Guwosari Village officially became members of the Wonolestari CFMU through a Members' Meeting. Besides Guwosari Village, there are additional new members, namely four hamlets in Triwidadi Village and two hamlets in Sendangsari Village.

Physical capital

It becomes less relevant in the context of SVLK introduction, because the focus of intervention is certification of timber production, or only focuses on the upstream part of the value chain. The community is relatively well-established in this part. However, Wonolestari CFMU also wants to develop a community-based wood processing industry that includes sawmills and wood drying for future development.[12] [13] This goal has the potential to present a gap in physical capital that requires further intervention.

Financial capital

Another important gap come from the financial capital. To obtain certification such as the SVLK, a large allocation of funds is required to meet certification costs.[11][14] So far, this need has been subsidized by the government or donors, but this approach is certainly not sustainable. The low market demand for SVLK-certified products[15] also makes this large spending less reasonable. SVLK certification based on smallholder FMU will increase production input costs by an average of 15%, assuming there are surveillance costs every two years.[11]

Social capital

One of the important assets in the SVLK intervention is the culture of "gotong royong" which is still strong among the people of Central Java. This also made it possible to encourage the establishment of forums for private owners of community forests. Gotong royong is loosely translated from Bahasa Indonesia as reciprocal cooperation or communal labor. The idea behind this philosophy is sharing of burdens among the member of the community. It can also be considered an obligation we hold as individuals in order to contribute to society. It is believed that when people work together, instead of separately, they will accomplish much more than if they were working by themselves-- not just economically but emotionally too.

The Stakeholders

The SVLK introduction to Wonolestari CFMU cannot be separated from the role of several key stakeholders. These stakeholders can be categorized as affected or interested.

Affected Stakeholders

Defined as any person, group of persons, or entity that is or is likely to be subject to the effects of the activities in a locally important or customarily claimed forest area.[16] Based on this definition, the affected stakeholder is the Wonolestari community which joined Wonolestari CFMU. They are the legal owner of the community forestry land. They earn a livelihood from the land and any activities that happened on the land will affect them.

Interested Stakeholders

Defined as any person, group of persons, or entity that is linked in a transaction or an activity relating to a forest area, but who does/do not have a long-term dependency on that forest area.[16] From this point of view, there are several interested stakeholders, namely:

- ARuPa NGO and LEI: they received funding from donors to assist the communities in improving their capacity in managing community forestry.

- Center for Standardization and Environment (PUSTANLING) Ministry of Forestry: they have an interest in piloting community-based sustainable forest management and awarding SVLK certificates as part of SVLK program to increase the legality of timber exports from Indonesia.

- Environmental and Forestry Agency at the provincial level: as an extension of the Ministry of Forestry at the sub-national level, they have an interest in supporting activities launched by the Ministry of Forestry regarding community-based sustainable forest management.

- Global/international organization as donors (EU, ITTO): In addition to aid disbursement, they also have an interest in improving the legality and governance of timber exports from Indonesia

- Third-party verfication body: a highlight of the SVLK system is the verification of timber provenance at every stage in the supply chain. Following this process, third-party verification agencies come into play for issuing Verified Legal Certificates (V-legal documents). Thus third-party verification agency fall into interested stakeholders category.

Much Needed Engagements

While it is understandable that the intervention coordinated by the Ministry of Forestry was focusing more on the upstream part of the value chain since this is in line with their mandate and scope of work, a better engagement with key stakeholders at the downstream part of the value chain was equally important. There are three reasons highlighted by business actors regarding their disinterest in a timber legality system such as the SVLK. The first is the lack of socialization from the government, the second is the lengthy process and costs involved, and the third is the lack of demand from end buyers for certified products.[15] Domestic timber buyers, customs, and the timber industry are some examples of downstream key stakeholders who need to be engaged because they could contribute to or jeopardize the implementation of SVLK. It is worth mentioning that the domestic market can be considered a “safety net” or alternative market that provides a more stable demand for timber producers.

Furthermore, due to the nature of the timber export value chain which is across sectors, coordination and collaboration between sectors and ministries are clearly room for improvement. It is crucial to create awareness among other sectors or ministries about the important role of SVLK in supporting Indonesian timber exports. By having a better understanding, it is expected that they will be more willing to support the system according to their duties and functions.

This last point is important, because in February 2020, the Government of Indonesia, through the Ministry of Trade, issued a regulation that revoke a requirement for wood exporters to obtain licenses verifying their wood comes from legal and sustainably managed sources. The decision was taken without sufficient communication and coordination with the Ministry of Environment and Forestry. The relaxation of the SVLK policy aimed to boost timber exports amid an economic slowdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. This decision has the potential to be detrimental in terms of state revenue. When the illegal timber trade becomes rampant, the potential for tax revenue from timber exports decreases.[17] Finally, after reaping a lot of criticism, the Minister of Trade revoked Regulation Number 15/2020 which abolished the SVLK provisions. Thus, provisions on the export of forest products refer to the previous regulation, i.e., Regulation of the Minister of Trade Number 84/2016.

Discussion

At The Field Level

The most important question with SVLK introduction is: does it really work to benefiting timber producers, including smallholders like communities in Wonolestari CFMU? With the agreement between the Indonesian government and the European Union to accept SVLK under the FLEGT (Forest Law Enforcement Governance and Trade) licensing scheme, exporters are exempted to test the legality of wood. Thus, SVLK significantly cuts costs for due diligence by around US$1,000-2,000 per 20-40 feet container. Smallholders of Wonolestari CFMU is now able to access European and American market. While the price that they received for SVLK certified product is 4-5% higher than the noncertified products.[12]

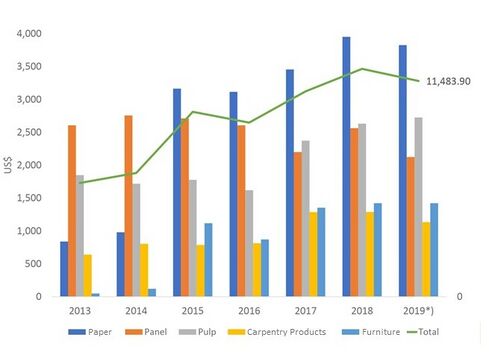

Furthermore, Government’s data for the value of timber exports also shows a significant increase since the implementation of the SVLK (see Figure 1). The highest export value occurred in 2018 of US$ 12.13 billion. This significant increase can be traced back to the application of V-Legal in the SVLK required by the European Union for limited types of exports.[18]

Source: Forest Digest, 2020

From the smallholders’ point of view, the application of international standards usually has implications for additional practices and administrative burdens. Research found that implementing SVLK standards amid multiple forest regimes causes redundancy of administrative procedures in forest management and timber trade in Indonesia. This redundancy, in turn, leads to a decrease in cost efficiency, weak legitimation, and low effectiveness of the system, especially in community forestry.[19]

Furthermore, complex regulatory frameworks applied to smallholder plantations, including Wonolestari—as explained in the tenure arrangement section—also leads to the high transaction cost. This, coupled with expensive certification costs, makes the total production costs that must be incurred by smallholders even greater. Regulatory frameworks are defined as not only regulations issued by public administrators at the domestic (local and national) level, but also cover emerging market-based regulatory frameworks, i.e. voluntary certification of sustainable forestry and mandatory timber legality verification.[9][20] This in turn leads to lower selling prices/profits for smallholders.

As a result, they become very dependent on middlemen or collectors to be able to sell the wood and earn money and avoid the administrative burden. They also face huge challenges when seeking commercial markets. The member of Wonolestari CFMU was unable to compete with cheap wood products from China.[12] Therefore, to survive, they have to focus on the niche market of high-end products with complex designs, which are lower in volume and higher in cost.

In recognition of these challenges, the Indonesian government has been making a series of changes to the SVLK legislation. For instance, V-legal certificates were initially valid for 5 years for all applicants regardless of the size of their business and the nature of forest ownership. This was later revised to grant small-scale industries and smallholders a longer certification period (10 years in comparison to 5 years for big industries. A more fundamental revision was then made by the government by the end of 2014. Through the issuance of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF) Decree No 95/2014, small-scale, legally recognized private forest plantation owners (mostly in Java), are excluded from the requirement to obtain legality certification and V-legal documents. Instead, they can issue a self-declaration document declaring that the timber is harvested from private forests.[21]

At The Governance Level

In a wider context, several studies found room for improvement for SVLK, especially from the governance side. While a focus on legality offers various strategic advantages to international and state actors, it faces its own challenges of authority and legitimacy. It is widely known that state capacity is limited in many developing country forests, and associated with problems of corruption, contradictory legal frameworks, etc.[22] Contradictory legal frameworks are common across sectors or between governance levels in Indonesia and this can be the main point that causes the full or partial failure of a system or policy. With the decentralization context in Indonesia, the unsynchronized regulations at different levels of governance can create distrust and lead to no support from higher or lower levels of government, which in turn will affect the policy process.

In addition to the contradictory legal framework, research found that the effectiveness of the SVLK implementation was low also due to relatively rapid policy changes.[11] This situation became disincentive for investments in the timber business because rapid policy changes equal to high business risks. Hence, the industry and market at the downstream of the value chain have not been fully supportive of this system.[15]

Another loophole within the SVLK is the third-party verification body. In addition to the limited number of verification body and lack of capacity, they aren't always trustworthy and can be bribed to approve timber from illegitimate sources and publish the V-Legal Certificates.[4] The decision to delegate the verification of legality to private, third-party auditors was supported by the EU and other stakeholders, based on the argument that it would reduce the risk of corruption in the auditing process.[23] Indonesia has suffered for decades from a rather negative reputation of widespread corruption and mismanagement of forest resources. Therefore, third-party verification was deemed necessary to restore the credibility of Indonesia’s forest industry to the rest of the world.[21] There should be a constant effort to improve the quality of third-party verification body.

Despite this widespread recognition of the role of corruption, this issue is not addressed by SVLK legality certification.[24] Instead, the focus of SVLK on the production of documents does not require or enable auditors to evaluate irregularities in how those documents are obtained. This leaves ample opportunity for bribery and has led one key informant to note that SVLK had been reduced to a system of administrative checklists, and to state that this hampers its potential to support broader efforts to improve forest governance.[21]

Strong coordination between institutions and ministries is key for anti-corruption measures since it involves multiple sectors and governance levels. Coordination can be strengthened by: (i) involving local governments in design, implementation and monitoring; (ii) spreading responsibility among all relevant institutions; (iii) establishing an institution with sufficient authority to serve as a facilitator; and (iv) providing sufficient resources for coordination.[25] The use of information and communication technology (ICT) and big data--as showcased from Brazil's efforts to combat ilegality in timber sector--can also strengthened accountability and transparency in anti-corruption measures.[25][26]

Conclusion and Recommendations

SVLK is a systematic effort by the Indonesian government to combat illegal logging, and at the same time to prove the legal status of timber from Indonesia. The implementation of the SVLK has brought a number of improvements to timber producers and the export value of Indonesia's timber and forest products. However, several challenges were also identified from the implementation of the SVLK, such as:

- Policy: rapid changes, contradictory legal frameworks, and redundant administration.

- Market: timber industry and buyers at the downstream of timber value chain are not supportive of the SVLK implementation. It is reflected in the low market absorption.

- Standard: complex requirements and cost expensive.

- Weak anti-corruption measures: several loopholes within the process and 3rd party verification body.

To achieve full SVLK compliance in the Indonesian forestry sector, particularly in the whole value chain, is not easy. However, with better governance, adequate information for all stakeholders, expanded capacity and trustworthiness for verification bodies, making the SVLK process simpler and more affordable, and opening up better access to the market-- there is hope for improvement. It is also important to acknowledge the important role of field facilitators such as NGO or field extensions to work with communities/small holders. In addition to that, when more robust anticorruption measures are put into place - this could be an instrumental factor that would lead to more sustainable forest management practices through sustainable certification.

This conservation resource was created by Course:FRST522. | |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Saturi, S (2016, January 01). "Wonolestari, hutan rakyat dari selatan Jogja". Mongabay Environmental News. Retrieved 2022, October 26. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Soraya, E (2018). "Model manajemen modern hutan rakyat: Perlukah?". In Maryudi, A. & Nawir, A.A. (ed.). Hutan Rakyat di Simpang Jalan. Yogyakarta, Indonesia: Gadjahmada University Press. p. 109. ISBN 9786023862580.CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)

- ↑ Nawir, A.A.; Murniati; Rumboko, L. (2008). Rehabilitasi Hutan di Indonesia: Akan Kemanakah Arahnya Setelah lebih Dari Tiga Dasawarsa?. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR - Center for International Forestry Research. ISBN 9789791412353.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Obidzinski, K., Dermawan, A., Andrianto, A., Komarudin, H., Hernawan, D., & Fripp, E. (2014). Timber legality verification system and the voluntary partnership agreement in Indonesia: The challenges of the small-scale forestry sector. CIFOR Working Paper 164. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR.

- ↑ Ministry of Environment and Forestry. (2019, October 11). Presiden Jokowi Tegaskan Komitmen Pemerintah Selesaikan Perhutanan Sosial Dan Reforma Agraria. [Press release] http://ppid.menlhk.go.id/berita/siaran-pers/5107/presiden-jokowi-tegaskan-komitmen-pemerintah-selesaikan-perhutanan-sosial-dan-reforma-agraria

- ↑ World Bank. (2021, October 25). Opening the door to community forest access and management in Indonesia. World Bank. Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2021/10/21/opening-the-door-to-community-forest-access-and-management-in-indonesia

- ↑ Safitri, M. A. (2022). Social forestry and forest tenure conflicts in Indonesia’, in Bulkan, J. et al. (Ed.) Routledge Handbook of Community Forestry. (pp. 15). Routledge.

- ↑ ARuPa. (2015, April 13). UMHR Wono Lestari Bantul lulus sertifikasi PHMBL. ARuPa - Aliansi Relawan Untuk Penyelamatan Alam. Retrieved December 5, 2022, from https://arupa.or.id/umhr-wono-lestari-bantul-lulus-sertifikasi-phbml/

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Maryudi, A., Nawir, A. A., Permadi, D. B., Purwanto, R. H., Pratiwi, D., Syofi'i, A., & Sumardamto, P. (2015). Complex Regulatory Frameworks Governing Private Smallholder Tree Plantations in Gunungkidul District, Indonesia. Forest Policy and Economics, 59, 1-6. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2015.05.010

- ↑ Scoones, I. (1998).Sustainable rural livelihood: a framework for analysis. IDS Working Paper No. 72. Institute of Development Studies. doi: 10.1080/03066150902820503

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Suryandari, E.Y., Djaenudin, D., Astana, S., & Alviya, I. (2017). Dampak implementasi sertifikasi verifikasi legalitas kayu terhadap keberlanjutan industri kayu dan hutan rakyat. Jurnal Penelitian Sosial Dan Ekonomi Kehutanan, 14(1), 19-37. doi:10.20886/jsek.2017.14.1.19-37

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Nuswantoro. (2016, September 28). Kala SVLK tak hanya komitmen kelola hutan rakyat lestari juga mudahkan ekspor perajin kayu. Mongabay Environmental News. Retrieved October 29, 2022, from https://www.mongabay.co.id/2016/09/28/kala-svlk-tak-hanya-komitmen-kelola-hutan-rakyat-lestari-juga-mudahkan-ekspor-perajin-kayu/

- ↑ Sumarno, S., Hesti Heriwati, S., & Dwi Hartomo, D. (2015). Efforts to keep forests sustainability and economic improvement for the community around Perum PERHUTANI through product design approach. Journal of Arts and Design Studies, Vol. 38. http://iiste. org/Journals/index. php/ADS/article/view/27409/28120, 38, pp. 41-50.

- ↑ Purbasari, D.D.T.P., Karuniasa, M., & Wardhana, Y.M.A.. (2020). Constrain of smallholder forest management on Timber Legality Assurance System (SVLK) certification: A case study in KTH enggal Mulyo Lestari, Ponorogo District, East Java Province. Journal from E3S Web of Conferences, 211. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202021105009

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Aditiasari, D. (2016, March 18). Sistem legalitas kayu tak diminati pengusaha, ini alasannya. Detik Finance. Retrieved October 29, 2022, from https://finance.detik.com/industri/d-3168075/sistem-legalitas-kayu-tak-diminati-pengusaha-ini-alasannya

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Bulkan, J. (2022, October, 24). Affected and interested stakeholders [PowerPoint slides]. Faculty of Forestry, University of British Columbia. https://canvas.ubc.ca/courses/102944/files/folder/Lecture%20slides?preview=23339348

- ↑ Nugraha, I. & Arumingtyas, L. (2020, March 26). Indonesia ends timber legality rule, stoking fears of illegal logging boom. Mongabay Environmental News. Retrieved December 17, 2022, from https://news.mongabay.com/2020/03/indonesia-timber-illegal-logging-legality-license-svlk/

- ↑ Forest Digest. (2020, May 16). Aturan penghapusan SVLK Dicabut. Forest Digest. Retrieved December 17, 2022, from https://www.forestdigest.com/detail/600/aturan-penghapusan-svlk-dicabut

- ↑ Nurrochmat, D. R., Dharmawan, A. H., Obidzinski, K., Dermawan, A., & Erbaugh, J. T. (2016). Contesting National and International Forest Regimes: Case of Timber Legality Certification for Community Forests in Central Java, Indonesia. Forest Policy and Economics, 68, 54-64. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2014.09.008

- ↑ Setyowati, A. & McDermott, C. L. (2016). Commodifying legality? who and what counts as legal in the Indonesian Wood Trade. Society & Natural Resources, 30(6), 750–764. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2016.1239295

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Setyowati, A. & McDermott, C. L. (2016). Commodifying legality? who and what counts as legal in the Indonesian Wood Trade. Society & Natural Resources, 30(6), 750–764. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2016.1239295

- ↑ McDermott, C. L., Hirons, M., & Setyowati, A. (2020). The interplay of global governance with domestic and local access: Insights from the FLEGT VPAs in Ghana and Indonesia. Society & Natural Resources, 33(2), 261-279. doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2018.1544679

- ↑ Cashore, B. and M. W. Stone. (2012). Can legality verification rescue global forest governance?: Analyzing the potential of public and private policy intersection to ameliorate forest challenges in Southeast Asia. Forest Policy and Economics.13-22.

- ↑ Obidzinski, K & Kusters, K. 2015. Formalizing the Logging Sector in Indonesia: Historical Dynamics and Lessons for Current Policy Initiatives. Society & Natural Resources 28: 530 -542.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Arwida, S.D., Mardiah, S., Luttrell, C. (2015). Lessons for REDD+ benefit-sharing mechanisms from anti-corruption measures in Indonesia: 12p. CIFOR Infobrief No. 120. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR. http://dx.doi.org/10.17528/cifor/005586

- ↑ Cox, L. (2022, August 24). Using big data to detect illegality in the tropical timber sector. BVRIO. Retrieved November 10, 2022, from https://www.bvrio.org/using-big-data-to-detect-illegality-int-the-tropical-timber-sector/