Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/2021/ The impact of community forests formalization on tenure security and forest management in Northern Thailand

Although the impact of formalizing community forestry through legal registration is unknown, it may improve the tenure security of local communities. Thailand's registration program was researched to see if it improved the tenure security of community forests and their management. Following registration, forest communities felt secure in the knowledge that their use and management rights would be protected. If forest officials and police gave assistance, the registration allowed communities to avoid additional forest encroachment and resolve issues. Limited financial resources, on the other hand, made it difficult for communities to maintain and monitor forests.

This conservation resource was created by Course:FRST522. | |

Introduction

Geography and Location

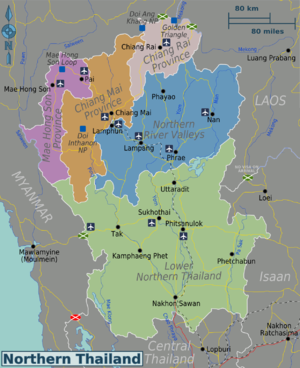

Thailand, located in the heart of mainland Southeast Asia, is a country of mountains, hills, plains, and a long coastline that stretches 1,875 kilometers along the Gulf of Thailand and 740 kilometres along the Andaman Sea, not including the coastlines of some 400 islands, the majority of which are in the Andaman Sea (Royal Thailand Embassy in Washington, DC). Thailand is split into 77 provinces (Changwat), which are separated into five geographical groupings. Bangkok (Krung Thep Maha Nakhon in Thai) and Pattaya are two special regulated districts that make up the country's capital.

Northern Thailand, or more precisely Lanna, is defined by multiple mountain ranges that stretch from Myanmar's Shan Hills to Laos, as well as the river basins that cut through them. Although it has a tropical savanna climate like the rest of Thailand, its higher height and latitude lead to more marked seasonal temperature change, with colder winters than the rest of the country. It has a historical connection to the Lanna Kingdom and its culture and it’s made of 17 provinces with sixty national parks.

According to official statistics, around 3 million people depend on Thailand's roughly 12,000 community forests, around 7,000 of which are registered with the Royal Forest Department (RFD)(Reuters, 2021). Community forestry is The management, conservation, and use of forest resources by local communities. In line with Thailand's 1997 Constitution, a community is defined as a social group living in the same region and sharing the same cultural heritage (RECOFTC, 2021, P.8). This version requires the community to apply for a community forest after five years of forest management expertise. In the RFD version, a community was defined as at least 50 people living near a forest, regardless of how long they had been there or how the forest was managed. This definition can be problematic as it can allow any group of 50 people to manage a community forest. Rather than maintaining the forest responsibly, they may utilize it to construct commercial crops, for example. (RECOFTC, 2021, P.8)

Brief History of Community Forestry in Thailand

Community forestry originated in Thailand in the 1980s, when local people formed groups to maintain and manage their surrounding forests in response to continued forest degradation (Pagdee et al. 2006). Traditional communal irrigation systems, particularly in northern Thailand, may have served as a springboard for Thailand's modern community forestry, in which irrigation groups were formed to protect local watershed trees (Jenke & Pretzsch, 2021, P.30). As a result of the state's absence, communities sought to safeguard nearby forests from illicit logging (Poffenberger and McGean 1993). In the early 1990s, communities in Thailand formed networks to push for the legal recognition of community forests, to strengthen communities' forest tenure rights through formal titles that followed customary laws (Colchester, 2002, p. 16). The government formed a committee of forest authorities and academics in 1990 to draft a Community Forest Act to formalize the expanding number of community forests (Weatherby and Soonthornwong 2007). The declared goal was to decrease tenure problems on state-owned forestland, which were caused by the high population density in these areas, as well as to restore degraded forests. Thailand's forest state officials began to recognize community forests in 2000. This formalization effort is based on a co-management strategy in which the community and the state share use, management, and exclusion rights through the Royal Forest Department, or RFD (Chankrajang, 2019, P. 263). However, following a series of arguments concerning the legalization of community forests within tightly protected regions, the Community Forest Act was only enacted in May 2019 (Jenke & Pretzsch, 2021, P.31).

As of 2019, there were over 11,327 recognized community forests covering over one million hectares. Now, the RFD plans to classify 1.6 million hectares of conserved forest as community forests by 2025. There will be 15,000 community forests that have been registered as part of this project (Jenke & Pretzsch, 2021, P.31).

Tenure and administrative arrangements

Tenure security is a critical component of community forestry's success (Baynes et al., 2015, P. 233). Arnot et al. (2011) defined tenure security as a tenure holder's anticipation of losing their tenure rights, or how confident they are that their rights would be protected by others around them. Van Gelder (2010) presented a broader definition of tenure security that takes into account both the perceived certainty of tenure rights and real (de facto) tenure security, i.e. enforcement independent of formal tenure status.

There are three levels of decision-making. National, provincial and community. The decision to allocate a community forest involves the local Forest Resource Management Office (FRMO), the PCF Committee and the RFD’s Director-General. The process can take as little as 130 days, as much as 220 days if many petitions are made at the same time, and as much as 355 days if there are objections and appeals. In addition, the legislation is unclear about the procedures that must be taken in each instance (RECOFTC, 2021). When two or more requests for the same region overlap, the parties will be urged to work out a deal to cancel one or combine the others. If no agreement can be reached, all requests are cancelled and deleted from the system (Interview response by one of RECOFTC project coordinator). Communities are left to make their own decisions, which might lead to conflict. Supporting rules should contain a legal mechanism that may be utilized to protect those who disagree with the request and avoid confrontations.

The Community Forest Act (2019) establishes the following method for community forest registration:

(1) On behalf of the community's people, the village head or a sub-district authority seeks to register the community forest.

(2) A signed permission from 50 community members, a map of the community forest area, and a formal management plan are all essential documentation.

(3) An RFD official and the provincial administrative organization must both authorize all papers.

(4) Communities acquire a certificate giving specific usage and management privileges upon registration.

(5) Every five years, the communal forest committee must modify its management plan. The registration is revoked if the community is unable to conserve its forest.

Affected and Interested Stakeholders

Affected Stakeholders

Affected stakeholders include minority groups such as the Karen, Hmong and Lawa and also the Thai. Each ethnic groups exhibit a significant desire to protect the environment. This is due to the growth of forest culture and customs, as well as the necessity to adapt to changing circumstances and environments, as well as external factors (Hares, 2006, P.99 ).

Non-timber forest products (NTFP) like mushrooms, bamboo shoots, and medicinal plants were an essential management priority for all communities, in addition to conserving the forest's protective ecological services (Jenke & Pretzsch, 2021).

Other affected stakeholders include smallholder farmers and local people including women that live in Northern Thailand. There is more cooperation between communities than conflict. However, villagers still face stringent control by the government over resources. Therefore, more collaboration between the government and the local people especially those living in or near protected areas is needed.

Interested Stakeholders

Interested stakeholders include academics that research the area, the private sector of farmers and government agencies such as the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation and the Royal Forest Department (RFD). Interested stakeholders also include ENGOs such as RECOFTC whose main objectives are (RECOFTC, 2021):

- Facilitate and influence policy discussions at the national and regional levels.

- Assist in the conception and development of a nationwide community forestry program.

- Assist in the creation of helpful institutions, systems, collaborations, and financing possibilities.

- Support the establishment of community forestry sites with technical assistance, including training.

- Support community forestry networks at the grassroots, national, and regional levels.

- Throughout the region, advocate for community forestry and build awareness about it.

- Provide community foresters with training and resources.

Another NGO that works in this region is the United Human Development Project (UHDP). The organization was founded by Baptist missionaries to assist resource-poor ethnic minority settlements near the Thai-Burma border. It provides community forestry and associated legislative training, as well as assisting communities in developing watershed networks (Roberts, 2016, P.56). These ethnic groups have faced a lot of racialization that has hindered their rights and control over their community forests (Roberts, 2016, P.56. Up to now, the government still dominates in decision making, there are 13 people from government agencies and only 7 civilians.

Discussion

As (Baynes et al., 2015 ) explained in their article, tenure security is one of the key factors that influence the success of community forestry in developing countries. According to Schlager and Ostrom's (1992) concept of a bundle of rights.' Local people can (1) access land and extract resources from it, (2) manage and enhance the property, (3) restrict others from it, and (4) sell or lease it. Holders of communal rights can choose how to invest in, use, and share forest resources thanks to management rights. Exclusion rights allow communities to safeguard forest resources from overexploitation by limiting other forest users' access or withdrawing their rights. Management rights include the capacity to make regulations, supervise compliance, and resolve problems (Agrawal and Ostrom., 2001, P.496). Management rights also allow holders of community rights to choose how to invest in, use and distribute forest resources (Agrawal and Ostrom 2001, Schlager and Ostrom 1992). When these rights are compromised, people’s excitement for community forestry diminishes (Baynes et al., 2015 P. 230).

Objective and rights under the Community Forest Act

According to an analyses done by RECOFTC, 2021:

- The Act lays forth the main goal of community forestry in Thailand: to ensure that people and communities benefit from forests while they are managed responsibly.

- Community forests are only allowed to exist legally outside of protected areas, which restricts communities' rights. For years, communities have practised community forestry outside of the prescribed forestlands and for non-conservation reasons that are not recognized under the Act.

- A minimum or maximum time for the allotment of a community forest is not required by the Act. It does not impose any restrictions on the size of a community forest. It states that the authorities will approve a five-year community forest management plan with the option of renewal.

What have been the successes?

Official acknowledgement and legal verification of a community's tenure claims have helped the community get access to the state's legal enforcement resources. Now communities more readily enforce their forest boundaries and eliminate rival tenure claims, increasing their tenure security. (Dahal et al., 2010). “We wanted to prevent from being further encroached,” said a resident of Rayong. Residents were worried that their urban forest will be cut down to make room for new housing developments..“Land here is very expensive, and we registered the forest before someone would clear it” (Jenke & Pretzsch, 2021, P.33). Pred Nai is seen as a triumph in the struggle for the right to maintain one of Thailand's last surviving mangrove ecosystems. The residents pushed their struggle to the next level, and the developers were forced to leave. Since then, the villagers have united to safeguard their mangroves, with everyone participating in making decisions that benefit their livelihoods.

Timber extraction is allowed in emergencies: "We enable villages to chop trees [for timber] if they have lost their home due to a fire and are unable to replace it." said RDF official, However, formalization can serve as a deterrent to unlawful deforestation (Jenke & Pretzsch, 2021, P.33). Forest cover is higher in forests with a larger area of community forests and these forests face lower fire frequency and intensity (Jenke & Pretzsch, 2021, P.33).

Income from NFTPs has also increased and is more stable now since the formalization of community forests. There is more market for products such as mushrooms, medicinal plants and bamboo shoots. The community forest program gives communities and the RFD a place to establish trust. As a result, Thai communities have probably gained greater control over forest management, a practice that has been promoted (Jenke & Pretzsch, 2021, P.33).

What have been the failures and conflicts

The Community Forestry Act is still new and might need some rectification. Some community tenure rights are not explicitly recognized under the Community Forest Act. For example, the Act is unclear on customary forestland rights and management rights, such as decision-making and power over forest use (Jenke & Pretzsch, 2021).

The Act does not explicitly address the rights of neighbouring communities. Collaboration among stakeholders, including residents of the community forest and neighbouring communities, is essential for successful community forest management. The community living near the community forest may be able to assist with forest management by patrolling or forming networks with neighbouring groups (RECOFTC, 2021).

In the community, internal governance, accountability, participation, and information sharing still need to be addressed. Women and racialized Indigenous people still need to be involved in the decision-making regarding their community forests given that they are the main users of the forests and therefore, the most knowledgeable of the forest.

Clear rules and conditions regarding conflict resolution and land claims still need to be developed. There is also a need for a map showing clear boundaries for all community forests. For example, two communities that were unable to address tenure issues after successful registration and delineation lost their de jure or de facto tenure rights over portions of their forest.

Finally and most importantly, the community forestry act excludes local and Indigenous people who live inside protected areas. Since they don’t have tenure security, they have to migrate several times. Hence affecting their food security and well-being.

Assessment of governance and the relative power of each group of social actors

Although community forests that have gained legal registration manage and control their forest, its registration is under co-management with the government, hence the government (usually RDF) has to approve before any project is implemented. During meetings, the government agencies are represented by 13 people compared to 7 civilians. Therefore, the government is still the most dominant actor.

Other important actors that haven’’t yet played an important role in the governance of these community forests are women. In an interview I had with the project coordinator of RECOFTC, she explained that women are the main users of forests as they collect most of the non-timber forest products. They are very knowledgeable about these forests yet don’t participate in decision-making. This is caused by the tradition and lack of gender balance priority. On the provincial level, formal meetings are made of 15% women and 5% at the community level. However, RECOFTC in Thailand is including more women in dialogues to increase their participation, and the goal is to increase their participation to 30% at the community level.

The next steps and Conclusion

Although tenure security is essential for the success of community forests, it’s difficult to isolate it from other direct and indirect drivers of forest degradation since it is so tightly linked to numerous socioeconomic and governance challenges. Although the legalization of community forests in Thailand has improved the management of forests and the autonomy of local people there are still some gaps to fill. First, the local people with the help of NGOs or government agencies need to understand the law. Some of the local people didn’t go to school. Second, there is a need for capacity building at the community level which RECOFTC has started working on. There is also a need to develop a proper conflict resolution protocol to avoid further land grabbing. Internal community governance and provincial governance should also work on improving participation and gender balance through inviting women and other minority groups to participate in different dialogues. Many community forests face financial restrictions. Therefore, those with ecotourism or Non timber forest products market opportunities should consider growing these business to gain more sustainable capital to better manage their forests.

All in all, the formalization of community forests in Northern Thailand has given local people management rights which allow them to choose how to invest in, use, and distribute forest resources. It has increased the enthusiasm of local people to care for their forests as they are now sure nobody will just come and take it away from them. It’s not all about tenure, but tenure security plays an important role in the success of community forestry especially in developing countries.

Acknowledgement

Many thanks to Kanokporn Deeburee a project coordinator at RECOFTC, for all the information provided during our semi-structured interview.

References

Agrawal, A., and Ostrom, E. (2001). Collective action, property rights, and decentralization in resource use in India and Nepal. Politics & Society 29(4): 485–514.

Arnot, C.D., Luckert, M.K., and Boxall, P.C. (2011). What is tenure security? Conceptual implications for empirical analysis. Land Economics 87(2): 297–311.

Baynes, J., Herbohn, J., Smith, C., Fisher, R., and Bray, D.( 2015). Key factors which influence the success of community forestry in developing

Community Forest Act B.E. 2562 (2019). https://www.informea.org/en/legislation/community-forest-act-be-2562-2019

Colchester, M. (2002). Learning lessons from the RECOFTC experience with community forestry networking. Ford Foundation and DFID (unpublished).

Cronkleton, P. and Larson, A, (2015). Formalization and Collective Appropriation of Space on Forest Frontiers: Comparing Communal and Individual Property Systems in the Peruvian and Ecuadoran Amazon. Society & Natural Resources 28(5): 496–512

DAHAL, G., LARSON, A., and PACHECO, P. (2010). Outcomes of reform for livelihoods, forest condition and equity. In: A. LARSON, D. BARRY, G. DAHAL and C.J.P. COLFER, eds. Forests for people: community rights and Forest Tenure

Hares, M. (2006). Community forestry and environmental literacy in northern Thailand: towards collaborative natural resource management and conservation.

Jenke, M., & Pretzsch, J. (2021). The impact of community forest formalization on tenure security and co-management in Thailand. International Forestry Review, 23(1), 29-40.

Johnson, C., and Forsyth, T. (2002). In the eyes of the state: negotiating a “rights-based approach” to forest conservation in Thailand. World Development 30(9): 1591–1605.

Pagdee, A., Kim, Y., and Daugherty, P.J. (2006). What makes community forest management successful: a meta-study from community forests throughout the world. Society & Natural Resources 19(1): 33–52. Google Scholar

Poffenberger, M. and Mcgean, B. (1993). Community allies. Center for Southeast Asia Studies, University of California, Berkeley.

RECOFTC. June (2021). Thailand’s Community Forest Act: Analysis of the legal framework and recommendations. Bangkok, RECOFTC.

Reuters (2021). Thailand's green goals threaten indigenous forest dwellers. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-thailand-landrights-forest-feature-idUSKBN29Q046

Schlager, E., & Ostrom, E. (1992). Property-rights regimes and natural resources: a conceptual analysis. Land economics, 249-262.

The Royal Embassy of Thailand in Washington DC (2021). Thailand in Brief. ttps://thaiembdc.org/about-thailand/thailand-in-brief/

Weatherby, M., and Soonthornwong, S. (2007). The Thailand Community Forest Bill. RECOFTC Community Forestry E-News.