Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/2021/Social Forestry and Ecosystem Restoration, Bukit Tigapuluh Landscape case study – Challenges and opportunities through the partnership of Social Forestry schemes

Social Forestry Discourse and Landscape in Central Sumatra

Social Forestry Discourse

The objective of social forestry in Indonesia is divided into three-dimension which are recognition, livelihood, and conservation. However, the implementation constraint faced various issues such as the land administration process (one map policy-related), political-economic interest, and institutional engagement (Fisher et al., 2018)[1]. The rising of social forestry also becomes an approach to promote the decentralization process, which means improving the role of local people in forest management and exercising their rights. With the multipurpose of the dimension offered by social forestry in Indonesia, social forestry is believed to be an attractive solution because the number of people who lack access to land into growing conflict become a common interest of community and state. Thus, community-based management promoting decentralization in its practices has become a preferred discourse and booming in Indonesia.

Historically, in Indonesia, the concept of social forestry is not a new idea. The inception arose when Law 41/1999[2] on forestry in general and its derivative government regulation related to community access to the forest (6/2007[3] revised into 3/2008[4]). Social forestry emerged after the designation of forest estate at the centralized regime (Suharto era) established through the top-bottom process has failed to manage the forest in the 1970s and village development program initiated. The development program was not entirely meant to decentralize rights (Moeliono et al., 2017)[5]. After the Suharto era fallen, the social movement driven by AMAN (Indigenous Peoples' Alliance of Nusantara - Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nasional [6]) in 1999 has promoted social forestry as an umbrella program, and long further in 2010-2014, the target of the Ministry of Forestry (MoF) was to devolve 7.9 million Ha of state forest to local communities. After that, in the Jokowi era, which response to the necessity of poverty alleviation and natural resource access in forest estate, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (change from MoF into MoEF) has its directorate general for PSKL (Social forestry and Environmental Partnership) with an ambitious target of 12.7 million Ha by 2020 [7] for social forestry as the way to devolve the rights to local community imposed through MoEF regulation 83/2016 [8].

Updated to the current condition, the aspirations of Omnibus Law 11/2020[9] through its derivative regulation Government Regulation no.23 / 2021 [10] and MoEF regulation No. 9/2021[11] revise the MoEF regulation 83/2016[8]. It is noted that the specific needs from farmers answered, particularly related to regulating the oil palm in the social forestry area. Previously, the oil palm dispute only allowed up to 12 years in a social forestry scheme and finally extended into 25 years with the obligation of mixing trees (agroforestry) in the SF area. Oil palm resolution and other points are also mentioned, including the extension period and other processes. Furthermore, the detailed schemes describe by (Pieter et al., 2021)[12] in table below.

| Scheme | Period | Right holder | Applicable in what forest category? | Confirmation process | Permit issued by |

| Community forest (izin usaha pemanfaatan hutan

kemasyarakatan (IUPHKM)) |

35 years and can be extended | Individual, farmer group, or cooperative | Protection and production forests | Bottom-up process. Follow the indicative map of social forestry (PIAPS). A proposal can be addressed to MoEF Minister or governor | Minister of MoEF or can be delegated to the governor |

| Customary forest (Hutan adat (HA)) | As long as CLC

exists |

Customary law community (CLC) (masyarakat hukum adat) | Bottom-up process. Customary community proposes customary forest stipulation to the minister of MoEF. | Legalized by local regulation (perda) or governor/regent/mayor's decree | |

| Village forest

(hak pengelolaan hutan desa (HPHD)) |

35 years and can be extended | Village institution | Protection and production forests | Bottom-up process. Follow the indicative map of social forestry (PIAPS). Proposals can be addressed to the MoEF Minister or governor. | Minister of MoEF or can be delegated to governor |

| Community

plantation forest (izin usaha pemanfaatan hasil hutan kayu pada hutan tanaman rakyat (IUPHHK- HTR)) |

35 year and can be extended | Farmer group, farmer groups, forest farmer cooperative, social forestry business group, joint business between professional/ individual who has experience supervising in forestry with local people | Production

forest |

Bottom-up process. Follow the indicative map of social forestry (PIAPS). Proposals can be addressed to the MoEF Minister or governor. Without the burden of business licensing of forestry state-owned enterprises, unproductive production forests are prioritized. It requires a guarantee of capital from financial institutions. | Minister of

MoEF and assessment and approval can be delegated to the governor or an official appointed by the governor |

| Forestry partnership (kemitraan kehutanan; NKK

(outside Java Island) and IPHPS (in Java Island)) |

35 years and can be extended | Group of local people | Conservation

forest (with scheme conservation partnership) and production forest |

Bottom-up process. In forestry state-owned enterprise For conservation, a partnership can be implemented in a nature conservation area (KPA) and nature

reserve area (KSA) |

Head of

Forestry State-owned enterprise MoEF through head of technical implementation unit |

On the terminology concept of regulation No. 9/2021[11], the formal “perhutanan social” (social forestry) permit becomes “persetujuan perhutanan sosial” (approval of social forestry). This has emphasized the mechanism of the government to regulate social forestry through legalization procedures. In addition, the term for a customary forest is instead considered as "penetapan" (determination), not approval. In addition, the BRWA (Customary Area Registration Agency) has identified 8.3 million Ha as a potential customary area. Nevertheless, MoEF identifies ± 1,090,755 Ha and has ratified 75 customary areas for a total of 56,900 Ha [13].

Unsurprisingly, several pieces of literature have informed the effectiveness and constraint of the implementation of Social Forestry. On the downside, one of the main articles (Moeliono et al., 2017)[5] mentioned that social forestry spirit such as devolution and democratization is often neglected due to the rigidness and lack of regulation clarity strictly imposed in formal-social forestry. Moreover, the governance of social forestry seems to be re-centralized, complex, and often contradictory or inconsistent. These issues lead to the impression that social forestry in Indonesia is driven by the state interest to dispose of the wicked problem, which does not strongly emphasize the empowerment aspect. Contrary, formal-social forestry that is assisted by external support (NGO, academic, and researcher) has developed the community institution in Gunung Kidul, Java (Kurniasih et al., 2021) [14]. Albeit initially assisted by an external factor in the top-down process to form forest user groups, the evolution of community forestry institutions has been shown by the changes of attitude, networking (both formal and informal), and capacity in a positive manner. Hence, the challenges of formal-social forestry that commonly are the uncertain inequity of social governance, including lack of devolution rights, might be an opportunity for the government and external actors to learn, support, and improve the contextual issues within the community institution.

In response to the wicked problem that driven the booming of Social Forestry (SF), another resolution tool was also offered by the central government of Indonesia. The Agrarian Reform ("Tanah Obyek Reforma Agraria," or TORA) is more exclusive than the SF. For TORA, the forest estate that disputes and overlaps with the claimant may be released into other land uses (APL) after reviewing and analyzing its historical clarity and boundaries that are reasonable to consider. However, implementing and achieving these policies and targets is relatively tricky and intricate. Tenure conflicts are frequently occurring on the land; to a certain extent, this intricacy has been identified as the primary reason for the failure in forest governance[15]. Furthermore, the issue of a land dispute in the forest estate is often confused by the advocacy that recommends TORA instead of SF that might not necessarily be the aspiration of the most local community regarding the bottom-up process, but only the interest of elites.

Landscape in Central Sumatera

In Sumatra, Indonesia, the current development-environment trade-off is the trend of oil palm plantation that started in the 1980s overlapped with the forest estate induced by companies through the conversion of forest estate into other land uses (APL). Moreover, the smallholders followed this pathway to convert forest for oil palm plantation independently but mostly informal and beyond government control since the 2000s - after the fallen order regime of Suharto[16]. Furthermore, the companies often have the mechanism of oil palm cultivation contracts with smallholders. However, the development process of conversion into oil palm invariably altogether with the informal land market establishment and the commodification of common village land (McCarthy, 2010)[17]. This process exacerbates the pressing issues faced in one landscape, such as Bukit Tigapuluh Landscape (Bukit Tigapuluh Landscape Historical Changes).

Bukit Tigapuluh Landscape is one of the remaining intact forests in Central Sumatra . Besides the landscape is the habitat of key species in Sumatra, e.g., Sumatran Tiger and Elephant Tiger[18]. The development acceleration exposed this landscape at in expense of sustainability (degradation and deforestation). The moving images - (Bukit Tigapuluh Landscape Historical Changes): visualizes the historical changes of the landscape from 1985 until recently (2021). Not until 2007, when the logging road construction was initiated (KKI Warsi et al., 2010)[19], the rapid development happening along with the forest loss after the accessibility was established that attracted exogenous processes to accelerate the deforestation.

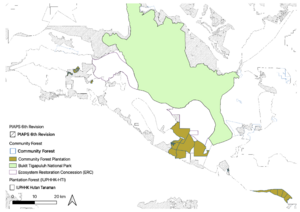

Based on the map from MoEF Webgis data[20], Landuse/Tenure Image illustrates detailed spatial land use/tenure in the landscape. Out of five schemes of Social Forestry in Bukit Tigapuluh Landscape, two schemes were established, namely Community Forestry (HKm) and Community Plantation Forest (HTR). Other schemes such as Customary Forest (Hutan Adat) and Village Forest (HD – Hutan Desa) are unavailable. Whereas the Forestry Partnership (Kemitraan Kehutanan) scheme, spatial data information remains close in internal of each company licenses, and not in the MoEF Webgis.

Juxtaposing the dynamic landscape historically (Bukit Tigapuluh Landscape Historical Changes) with the tenure established formally (Landuse/Tenure Image), the "informal" development process might occur mostly not overlap with the PIAPS (Map of Indicative Area for Social Forestry), HKm, or HTR. However, in the private companies (ERC and IUPHHK-HTI), the potential areas for Kemiteraan (Forestry Partnership) may be higher when the informal process is mostly undertaken beyond the control of the government and forest management unit (e.g., in (McCarthy, 2010)[17]).

Social Forestry (SF) and Land Object Agrarian Reform (TORA) for Justice

The initiatives of the SF and TORA[21] were driven by the issue of poverty and lack of natural resource accessibility of marginalized communities (Moeliono et al., 2017)[5]. While in the previous section, the dynamic discourse history has emerged since the 1970s for social forestry, the agrarian reform ideas were far before the colonial era (Saraya, 2019)[22]. In the colonial era, the central colonial government of the Dutch enforced the mechanism of land ownership through HGU (Hak Guna Usaha – Cultivation Rights) as a state asset that could use as collateral to apply for loans. Moreover, in the independence period, the transition of nationalization of the Dutch company, e.g., Perhutani, was undertaken. National policy related to private plantation has been imposed, and benefits conglomerate private estates. Not until recently, in the Jokowi Era, the Nawacita 5th Agrarian Reform is a follow-up process of the general view from National Long-term Development Plan (RPJPN - Law No. 17 of 2007[23] and - President Act No 86/2018[24]) into detailed prominent objective targeting 9 million Ha for agrarian reform for various type of purposes by 2019[22]. However, in the process of land dispute reconciliation in the forest estate (PPTKH) conducted by multi-sectors and ministries, the lack of dissemination information entails insufficient community capacity to formalize their legality may harm their tenure security (Nazir Salim et al., 2021)[25].

In addition, the imbalance of benefit distribution to land access, e.g., elite-privates versus the marginalized community, hinders the process of TORA objectives and obscures the actual needs for redistribution land for poverty alleviation with the rapacity of minor population. In (Saraya, 2019)[22] and (IPAC - Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict, 2014)[26] mentioned that, formally, based on National Land Agency (BPN) the land ownership over 56 % of the land and property is owned by minor population (0.2 %). Nevertheless, they argue that agrarian reform will not be the solution for redistributing the rights since the current formal private is still found unfair tax payment. Also, the notion of land reform driven exploitatively from the issue of indigenous rights (adat land) may trigger another horizontal conflict between indigenous and migrant[26]. The informal power over the land triggered by the informal land market (McCarthy, 2010)[17] distorts reality. It is often beyond the control of authority who exercise the governance effectiveness to achieve justice for one that is rightful.

Justice for the devolution of rights to the community can be viewed into two paradigms: distributive justice and procedural justice. While it is noted that the distribution equity of the rights and burden is exclusively tied to the distributive understanding of social justice, procedural justice focuses on the understanding of the process to achieve recognition, participation, and redistribution (de Royer et al., 2018)[27]. In the SF context, (de Royer et al., 2018) further concluded that the SF policy in Indonesia mainly restricts the equitable distribution of benefit, which often ignores the aspect of participation and recognition. It fails to achieve empowerment and social justice. On the other hand, TORA implementation is constrained by the lack of community capacity, which implies the minimum of participation and empowerment from PPTKH (Nazir Salim et al., 2021)[25]. Also, the policy of TORA is mainly driven by the redistribution of land that is often blurred by the contextual complexity in the ground and political interest by elites (e.g., political contestation of Anak Dalam Tribe ("SAD113") issue in (IPAC - Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict, 2014)[26]).

However, in the interview with the General Secretary of the Working Group for the Acceleration of Social Forestry in Jambi Province (POKJA PPS, Jambi, Arifadi)[28], he conveyed that "both SF and TORA are indeed mutually reinforcing programs in relation to agrarian reform in general. TORA may be more attractive for the community because it provides 'land ownership rights', but Social Forestry is only 'access to management', but the TORA can only be applied to certain cases". He further elaborates that the SF conceptually is still maintaining the objective of the ecological approach of forest area while in TORA, for transferring the land ownership, it will be uncertain to achieve its approach since it depends on the owner land use decision.

Arifadi[28] then mentioned that the objective of the SF in the landscape of Bukit Tigapuluh is generally aligned with the national policy vision. The goal is to improve welfare for farmers, sustainable forest management that achieves the aspect of ecological function, economic development and social inclusion, and being part of conflict resolution. The tenurial conflict is frequent in the Bukit Tigapuluh landscape. However, the SF offered to be part of its resolution experience constraints with the mutual understanding of the SF concept among multi-stakeholders (government, companies, and NGOs) that are often different and biased. Also, the insufficient capacity of the community encompasses the institution, business development, and forest management, which are essential points to address.

Social Forestry vs TORA (issue) in Ecosystem Restoration Concession

Specifically, Social Forestry becomes a part of the starting point to engage and negotiate with communities in the complex conflict case in the Alam Bukit Tigapuluh - Ecosystem Restoration Concession (ABT-ERC). Furthermore, an interview was conducted with the Community Development Assistant Manager of ABT-ERC (Habibi)[29]. He conveyed that the pressing problem that clashed with the ERC objectives in ecological restoration is the pre-existing communities (dominated by migrants) occupying the concession area that becomes the main driver for the forest loss (conversion into oil palm plantation). Generally, an updated MoEF regulation No.9/2021[11] is the feedback of the protest from informal oil palm plantation farmers. However, another actor’s interest in the area intentionally maneuvers the issue into another pathway, such as TORA, which confuses the communities. Moreover, the community's misinformed objective of ecosystem restoration is often perceived as the threat of insecurity if the ABT-ERC grabs their land. “The communities which not accommodated by social forestry (> 5 Ha claimed) was informed by this actor, will be excluded from and taken over by the ERC. Meanwhile the ABT-ERC committed not to take over the land, instead of following the regulation (No. 9/2021[11]) which also regulate this dispute and they (community’s land with >5 Ha) should propose their own permits” (Habibi).

The ABT-ERC approach strategy is to disseminate the social forestry policy to reduce the tension with the community. Furthermore, the community participation of social forestry started with the participatory mapping to recognize their claim, into the formulation of Cooperation Agreement (NKK) that agreed together between two parties. Habibi[29] mentioned that in his focus area, he managed to achieve two NKK. He believes it could change other communities’ perceptions and contestation interest actors in the area. “The community's perception is often more receptive if the program is mainly communicated as policy regulation implementation instead of the ecological restoration program. Therefore, the conversation with the community initiated as the restoration program can easily be misinformed by other actors. However, through formal social forestry regulation, we merely implement the government program as the alternative win-win solution which has more reasonable and acceptable for the community” (Habibi)[29].

On the other hand, the stages of policy implementation for social forestry comprise initial formulation, formal handover, and policy implementation (Sahide et al., 2020)[30]. In the case of the ABT-ERC, the formulation of NKK is part of the process for the initial formulation. The long iterative process still needs to consider the continuity and follow-up action. One of them is the role of central government MoEF to ratify the SF proposal that might be different in the new policy of the SF program. (Sahide et al., 2020)[30] argues that “in the past that the process of SF proposal may be extremely bureaucratic, but currently since the state interest is expediting formal handover to meet targets. As a result, at the time of approval, local actors may not have a proper understanding of policy and plans”. Therefore, the role of the ABT-ERC in facilitating social forestry will be crucial to ensure that the mutual understanding of planning and implementation, rights and burden, and hopefully develop the social capital such as in (Kurniasih et al., 2021)[14].

The process of determining justice driven by conservation-based projects often criticizes that overlook the social inclusion and recognition of indigenous communities. For instance, the policy of fortress conservation that established ‘national parks’ such as in the US that applied worldwide has violated the rights of indigenous people and impoverishment them (Colchester, 2004)[31]. However, in the ABT-ERC case, one prominent block area is very different from responding to the dynamic landscape from exogenous processes (migrant, elite actors, NGOs). In the western part (Block 2) has been mentioned by Habibi that the characteristic of societal constraints, and tension, reflect the various dynamic influence of economic consideration. In contrast, in the eastern part (Block 1), the indigenous people "Talang Mamak" live traditionally protecting and managing forest communally through local wisdom (informal social forestry?), leading to a better ecosystem restoration outcome. Although the Talang Mamak communities were hesitant to follow the formal social forestry process, they implemented traditional practices such as traditional agroforestry, controlled shifting cultivation, and NTFP (Titisari et al., 2019)[32]) has almost satisfied the objective of social forestry. Therefore, the Talang Mamak's engagement in the conservation areas is vital, instead of the fortress conservation that may need to exclude the traditional activity such as shifting cultivation.

Typology, challenges, opportunities, social-ecological restoration

In achieving the social forestry in ecosystem restoration program which part of being resolution conflict, the definition of different type so-called typology of the communities is defined. This typology comprises the indigenous and local community, smallholder migrants, and elites. On the other hand, the time history dimension, such as the historical forest cover, may indicate the physical changes, yet the dynamic social structures require further understanding.

Regarding indigenous people in Bukit Tigapuluh Landscape, Arifadi[28] mentioned that this landscape is the dwelling for Orang Rimba (often referred to as Anak Dalam Tribe - ADT) and Talang Mamak. While the Talang Mamak lives in the forest practicing farming, Orang Rimba lives in semi-sedentary to nomadic and depends on the forest for their livelihood. “I think both Orang Rimba and Talang Mamak have received social recognition as indigenous peoples. Not long ago, the Regent of Tebo (Regency in Bukit Tigapuluh Landscape) issued a decree on the recognition and protection of the Indigenous Law Community (MHA) ADT the Temenggung Apung Group in Muara Kilis Village and the Temenggung Ngadap Group in Tanah Garo Village” (Arifadi)[28].

The Talang Mamak

Talang Mamak community is one of the indigenous (Proto Malay) communities living inside the forest of Central Sumatera, Bukit Tigapuluh Landscape. It is in two Province: Riau and Jambi. They have a traditional norm in agriculture in their livelihood (AMAN, 2012)[36]. The activity in farming requires shifting cultivation, hunter and gather, and collection of the NTFP (Non-Timber Forest Product). In Riau Province, the origin story of Talang Mamak is the first tribe that came to the Indragiri River region that people call “Tuha Tribe.” At the same time, other people also mentioned that the Talang Mamak tribe came from the Pagaruyung area who moved due to conflict between adat (custom) and religion (Titisari et al., 2019)[32]. The tribe consist of 29 clan (suku/kebatinan) and spread in 3 main rivers; Ekok, Tenaku/Cenaku, and Gangsal (PPPM, 2017)[37]. The indicative territory location[38] is depicted in Location of Talang Mamak and overlapping tenure , overlapped with oil palm, acacia, rubber plantation, settlement, and national park (Bukit Tigapuluh National Park).

On the other hand, in Jambi, Talang Mamak Simerantihan came to the former concession, namely Dalek Hutani Esa, a logging concession since the 80s, and ended its license in 2003. Since 2003, the activity of Talang Mamak in Jambi has been collaborative with the existing NGO – FZS (Frankfurt Zoological Society), and with the pre-existing village (an old Malay village, namely Suo-suo). Talang Mamak has been recognized as an indigenous community, but it does not have a formal customary area (Hutan Adat). It overlaps existing tenure, national park, HGU, plantation forest, and ecosystem restoration concession. Therefore, the territory has been assigned to a particular zoning system and partnership with each license holder in a conducive area. In contrast, dispute areas (in Riau) occurred in HGU oil palm plantation related to the National Land Agency (BPN) decision for issuing a certificate that ignores the customary land (Charin & Hidayat, 2019)[39].

The Talang Mamak and Migrant on the Social Forestry

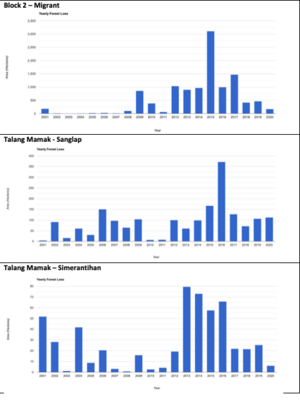

Talang Mamak protects the remaining forest in the landscape since their subsistence depends on the existing forest ecosystem. This has been emphasized by the dynamic presence of migrants that are attracted to clearing the areas' land. However, the Talang Mamak territory has established that they are protecting their forest territory from 'outsiders' to ensure the rotation of shifting cultivation is sustainably enough for the next generation. In Location of Talang Mamak and overlapping tenure , the two area of Talang Mamak are overlap in forested area (Sanglap; Bukit Tigapuluh National Park and Simerantihan; ABT-ERC, Rubber Concession, and National Park). In contrast, in the migrant-dominated areas such as in Block 2, forest cover loss was significantly higher with around 3,100 Ha loss in 2015, while in Sanglap, 373 Ha in 2016, and Simerantihan 79 Ha in 2013.

Furthermore, the challenges of social forestry in the migrant-dominated area are defined by who has proper benefit rights and burden and the accessibility to market for alternative income from the forest area, and the intervention actors contested in the landscape alter the perception of forest function. It is noted that in the MoEF No.9 2021[11], the oil palm plantation of the smallholders accommodated in the regulation schemes is less than 5 Hectares per person, and more than five years since the regulation was imposed. Therefore, the engagement for social forestry to the elites who claim the land more than 5 Ha requires further consideration. This consideration includes historical clarity and boundary (Harbi et al., 2021)[15]. Moreover, the relatively higher return of palm oil compared to rubber altered the deforestation process such as (L.R, Wibowo; D.H. Race;A.L, 2018)[41] that eventually led to establishing an informal land market (McCarthy, 2010)[17]. The elites are also altering the perception that land grabbing will be taking place because of the insecurity of their ineligibility and establishing support and power from others eligible for social forestry schemes.

Contrary, in the indigenous community (Simerantihan territory), the situation is more conducive. However, they hesitate to participate in the formal social forestry schemes since they think the area should be recognized as their territory, not the ecosystem restoration concession. The affirmative of the social forestry program that stated the partnership in the concession area will be perceived as the ‘hand over’ territory area to the ERC. While the local NGO advocates the territory into the customary forest land, the local old village Suo-suo that pre-existed objects to this plan. This is because the Suo-suo smallholders who usually work for Dalek (former logging concession) also have claimed in the ERC area, and the administration of Simerantihan are inside the Suo-suo village.

Other considerations that become obstacles are the accessibility to market, uncertain and vulnerable smallholder SF business, and the limitation of the capacity of smallholders (L.R, Wibowo; D.H. Race;A.L, 2018)[41]. In the business usual, oil palm plantation has its demand and value to support the business; however, there is uncertainty if the smallholders require to change the commodity into forestry or the NTFP. The limitation of community’s capacity become the reason of land market establish – smallholders decide to sell the land because it is easier, instead of managing their own land[41].

Implementing formal social forestry is part of the strategic conflict resolution engagement with pre-existing oil palm plantations. The concept of ‘jangka benah’[42] for mixing trees or agroforestry regulates by MoEF No 9/2021[11]. However, communities perceived that oil palm could not be mixed with other trees or plants. Oil palm farmers do not want to risk increasing the cost of planting mixed oil palm and trees because they doubt its feasibility. In response to this perception, research studies of agroforestry oil palm clarify this perception. Furthermore, the introduction of agroforestry in oil palm may improve soil quality, explained by (Gomes et al., 2021)[43], and increase biodiversity (Teuscher et al., 2016)[44], which also potentially increases yield production (Gérard et al., 2017)[45]. Therefore, one of the lessons learned from the studies to implement agroforestry may apply to conflict resolution, such as in the ERC (Subarudi et al., 2021)[46].

Moreover, the ABT-ERC managed to achieve the agreement with communities because the SF's legalization provides a sense of security. “The community that willing to participate in the social forestry simply because they feel secure to be legal and no longer needs to worry of their status” (Habibi)[29]. Contrary, it is noted that ownership rights are limited to rights of use (Moeliono et al., 2017)[5]. The stronger relationship with the land by the dimension of power and time may seem to alter the decision to collaborate in formal social forestry. The elites who informally planted the oil palm may feel insecure if they join social forestry that limits the area to 5 Ha[29]. Even after the study tour and socialization for agroforestry mixed-oil palm conducted research demo plot sample in Batanghari[47][48], smallholders has been influenced to not participate in the formal SF by elites. In contrast, the indigenous community the Talang Mamak is reluctant to join because they think they should get ownership instead of management use.

In addition, (Kurniasih et al., 2021)[14] explained that the community forestry institution evolves through an iterative process from the emergence, institution evolution, and transition implementation process. The current engagement in the formulation of NKK may be viewed as the process of emergence of community institutions that usually in a form Forest User Group (KTH). While it is facilitated by the external factor (ERC), the iterative process hopefully will achieve participation and the institution's development and implementation toward the Forestry Partnership objective.

The ecological restoration objective mainly aims to restore biodiversity side will never succeed if not aligned with the conflict resolution process that becomes a trade-off decision of socio-economic and environment. On the one hand, the formal social forestry partnership is not the only one for conflict resolution but seems very useful as an entry point to having the conversation and relieving the tension. Providing a shared understanding and win-win solution is necessary but also requires iterative and continued processes (Kurniasih et al., 2021)[14]. The way of social forestry in Indigenous activity should also respect, recognize, and learn their local wisdom for traditional agroforestry and finally restore the mindset like Habibi[29] mentions in the interview, “Restoration mindset for social engagement”. He referred to the other team, such as the rangers in ABT-ERC, who needs to incorporate the social development activity, not solely the assertive approach of patrolling and protecting the forest.

References

- ↑ Fisher, M. R., Moeliono, M., Mulyana, A., Yuliani, E. L., Adriadi, A., Kamaluddin, Judda, J., & Sahide, M. A. K. (2018). Assessing the New Social Forestry Project in Indonesia: Recognition, Livelihood and Conservation? International Forestry Review, 20(3), 346–361. https://doi.org/10.1505/146554818824063014

- ↑ "Undang-undang 41 Tahun 1999 Republik Indonesia (Law No 41/1999 dated 30/09/1999 on Forestry)" (PDF).

- ↑ "Government Regulation No. 6/2007 on Forest Systems and the Formulation of Forest Management and Use" (PDF).

- ↑ "Government Regulation No. 3/2008 on Amendments to Government Regulation No. 6/2007 on Forest Systems and the Formulation of Forest Management and Use" (PDF).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Moeliono, M., Thuy, P. T., Bong, I. W., Wong, G. Y., & Brockhaus, M. (2017). Social forestry-why and for whom? A comparison of policies in vietnam and Indonesia. Forest and Society, 1(2), 78–97. https://doi.org/10.24259/fs.v1i2.2484

- ↑ "AMAN".

- ↑ [Dirjen PSKL] DirektoratJenderal Perhutanan Sosial dan Kemitraan Lingkungan. (2015). Rencana Strategis 2015-2019. Jakarta, Indonesia: Kementrian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Ministerial Decree No. P.83/MENLHK/SETJEN/KUM.1/10/2016 on Social Forestry (Perhutanan Sosial)" (PDF).

- ↑ "Omnibus Law Indonesia 2020" (PDF).

- ↑ "Government Regulataion No 23/2021" (PDF).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 "MoEF Regulation No 9/2021" (PDF).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Pieter, L., Utomo, M. M. B., & Siagian, C. (2021). Implications of omnibus law for forestland conflict resolution systems (a case study in Sumbawa). IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 917(1), 012019. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/917/1/012019

- ↑ "Badan Registrasi Wilayah Adat".

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Kurniasih, H., Ford, R. M., Keenan, R. J., & King, B. (2021). The evolution of community forestry through the growth of interlinked community institutions in Java, Indonesia. World Development, 139, 105319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105319

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Harbi, J., Cao, Y., Milantara, N., Gamin, Brian Mustafa, A., & Roberts, N. J. (2021). Understanding people−forest relationships: A key requirement for appropriate forest governance in South Sumatra, Indonesia. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(13), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137029

- ↑ Euler, M., Schwarze, S., Siregar, H., & Qaim, M. (2016). Oil Palm Expansion among Smallholder Farmers in Sumatra, Indonesia. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 67(3), 658–676. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-9552.12163

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 McCarthy, J. F. (2010). Processes of inclusion and adverse incorporation: Oil palm and agrarian change in Sumatra, Indonesia. Journal of Peasant Studies, 37(4), 821–850. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2010.512460

- ↑ "Bukit Tigapuluh".

- ↑ KKI Warsi, Frankfurt Zoological Society, Eyes on the Forest, & WWF Indonesia. (2010). Last Chance to Save Bukit Tigapuluh. www.wwf.or.id

- ↑ "WebGIS SIGAP MOEF".

- ↑ "Sekilas Tora".

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Saraya, S. (2019). The Implementation of Agrarian Reform in the Settlement of Social Forest Management for Forest Village Communities (The Overview of Social Forestry Areas in Kendal Regency). https://www.atlantis-press.com/proceedings/icils-19/125922718

- ↑ "Undang Undang No 17 2007".

- ↑ "President Act No 18 2018" (PDF).

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Nazir Salim, M., Wulan, D. R., & Pinuji, S. (2021). Reconciling community land and state forest claims in indonesia: A case study of the land tenure settlement reconciliation program in south sumatra. Forest and Society, 5(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.24259/fs.v5i1.10552

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 IPAC - Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict. (2014). INDIGENOUS RIGHTS VS AGRARIAN REFORM IN INDONESIA: Report Subtitle: A CASE STUDY FROM JAMBI.

- ↑ de Royer, S., van Noordwijk, M., & Roshetko, J. M. (2018). Does community-based forest management in Indonesia devolve social justice or social costs? In International Forestry Review (Vol. 20, Issue 2).

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Semi-structure Interview. Arifadi Budiarjo December 11, 2021

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 Semi-structure Interview. Habibi. November 12, 2021

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Sahide, M. A. K., Fisher, M. R., Erbaugh, J. T., Intarini, D., Dharmiasih, W., Makmur, M., Faturachmat, F., Verheijen, B., & Maryudi, A. (2020). The boom of social forestry policy and the bust of social forests in Indonesia: Developing and applying an access-exclusion framework to assess policy outcomes. Forest Policy and Economics, 120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2020.102290

- ↑ Colchester, M. (2004). Conservation policy and indigenous peoples. In Environmental Science and Policy (Vol. 7, Issue 3, pp. 145–153). Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2004.02.004

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Titisari, P. W., Elfis, Zen, I. S., Khairani, Janna, N., Suharni, N., & Sari, T. P. (2019). Local wisdom of Talang Mamak Tribe, Riau, Indonesia in supporting sustainable bioresource utilization. Biodiversitas, 20(1), 190–197. https://doi.org/10.13057/biodiv/d200122

- ↑ "GIS BRWA".

- ↑ "GFW Oil Palm Plantation Concession".

- ↑ "MoEF WebGIS".

- ↑ Aliansi Masyarakan Adat Nusantara (AMAN). (2012). TALANG MAMAK: HIDUP TERJEPIT DI ATAS TANAH DAN HUTANNYA SENDIRI-POTRET KONFLIK KEHUTANAN ANTARA MASYARAKAT ADAT TALANG MAMAK DI KABUPATEN INDRAIRI HULU, PROVINSI RIAU DENGAN INDUSTRI KEHUTANAN OLEH: GILUNG, ANGGOTA MASYARAKAT ADAT TALANG MAMAK.

- ↑ Pusat Penelitian dan Pengabdian kepada Masyarakat (PPPM). (2017). PERSOALAN AGRARIA KONTEMPORER. www.pppm.stpn.ac.id

- ↑ "Peta WebGIS BRWA - Badan Registrasi Wilayah Adat".

- ↑ Charin, R. O. P., & Hidayat, A. (2019). The Efforts of Talang Mamak Indigenous People to Maintain Their Existence in Customary Forest Resources Battle. Society, 7(1), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.33019/society.v7i1.78

- ↑ Hansen, M. C., Potapov, P. v., Moore, R., Hancher, M., Turubanova, S. A., Tyukavina, A., Thau, D., Stehman, S. v., Goetz, S. J., Loveland, T. R., Kommareddy, A., Egorov, A., Chini, L., Justice, C. O., & Townshend, J. R. G. (2013). High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science, 342(6160), 850–853.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 L.R, Wibowo; D.H. Race;A.L, C. (2018). Policy under pressure : policy analysis of community-based forest management in Indonesia. The International Forestry Review, 15(3), 398–405.

- ↑ "Jangka Benah".

- ↑ Gomes, M. F., Vasconcelos, S. S., Viana-Junior, A. B., Costa, A. N. M., Barros, P. C., Ryohei Kato, O., & Castellani, D. C. (2021). Oil palm agroforestry shows higher soil permanganate oxidizable carbon than monoculture plantations in Eastern Amazonia. Land Degradation and Development, 32(15), 4313–4326. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.4038

- ↑ Teuscher, M., Gérard, A., Brose, U., Buchori, D., Clough, Y., Ehbrecht, M., Hölscher, D., Irawan, B., Sundawati, L., Wollni, M., & Kreft, H. (2016). Experimental biodiversity enrichment in oil-palm-dominated landscapes in Indonesia. Frontiers in Plant Science, 7(OCTOBER2016). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01538

- ↑ Gérard, A., Wollni, M., Hölscher, D., Irawan, B., Sundawati, L., Teuscher, M., & Kreft, H. (2017). Oil-palm yields in diversified plantations: Initial results from a biodiversity enrichment experiment in Sumatra, Indonesia. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 240, 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.02.026

- ↑ Subarudi, Gangga, A., & Sari, G. K. (2021). Unbalanced partnership scheme between community plantation forest and company: study case in West Kotawaringin, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 917(1), 012027. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/917/1/012027

- ↑ "CRC Oil Palm EFFORTS".

- ↑ "Efforts, CRC" (PDF).