Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/2021/Point Grondine Park, Ontario: An Example of Effective Indigenous-led Community Forest Use

Abstract

Point Grondine Park is the only Indigenous owned and operated park that has been built by the community from the ground up[1]. Point Grondine Park located along the shore of Georgian Bay was established on more than 7,000 hectares of Wiikwemkoong reserve land. As a community forest, Point Grondine Park serves both the Anishinabek of Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory and the visiting public, which it first began welcoming in 2016. The founding of the park was intended to protect Wiikwemkoong’s traditional territory from degradation, develop a sustainable source of income and employment for the community, and to educate the public about Anishinaabe culture, land, and history[2].

It has met with great success with an exponential increase in visitors and plans for further development of park amenities. A number of partnerships within the Wiikwemkoong community and with outside organizations, businesses, and agencies have helped to bolster the park’s ability to meet community goals[3]. All while maintaining community access and user rights. This case study examines the history, power structures, successes, and issues facing the future of Point Grondine Park. At the conclusion recommendations have been made for improving the current tenure system and cautioning against increasing tensions between non-Indigenous local communities and Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory as they move forward with the Islands Boundary Land Claim and what it could mean for the future of Indigenous community forests like Point Grondine Park.

Point Grondine Park is a precedent setting initiative in Indigenous-led community forestry which does not rely on resource extraction to support itself. This model has serious implications for Indigenous self-determination and land use rights. The Point Grondine Park model may be applied to other Indigenous communities to support employment, economic development, and environmental protection.

Description

Point Grondine Park (PGP) is a First Nations owned and operated park that is governed by the Anishinabek of Wiikwemkoong[i] Unceded Territory in the Georgian Bay region of Ontario, Canada[2]; a region listed as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve[5]. PGP covers an area of 7,284 hectares, and is set within the 34,000 hectare Point Grondine Reserve[1]. The Park is roughly 80km south of Sudbury and 400km north of Toronto. PGP is located in the Great Lakes – St. Lawrence Forest region, an ecological biome covering roughly 20% of Ontario’s landmass[6]. This ecological biome is comprised of mixed hardwood forests of species like Red Maple (Acer rubrum) and Yellow Birch (Betula alleghaniensis) and coniferous trees such as Red Pine (Pinus resinosa) and White Pine (Pinus strobe)[6]. It is also the habitat of many carnivorous predators, large ungulates, and smaller mammals including a variety of migratory bird species. Point Grondine Park encloses 8 interior lakes, wetlands, creeks, ponds, and rolling ground covered in a mixed hardwood-softwood forest which contains at least two stands of old growth[7]. PGP has a multitude of hiking trails, canoe and kayak routes, and campsites. It also hosts a variety of indigenous led programming featuring traditional skills, knowledge, and community history[2]. It began welcoming visitors in 2016, though the work to establish the park had been ongoing for more than a decade prior[1]. Situated close to Killarney Provincial Park, PGP is perfectly positioned to welcome day visitors from Killarney and to take advantage of overflow from the provincial parks.

It also serves the community of Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory (WUT), a First Nation whose territory is centred on Manitoulin Island and the surrounding smaller islands and mainland. A nation comprised of the Odawa, Ojibwa, and Pottawatomi who together form the Three Fires Confederacy[8]. The land of Point Grondine Park and the wider reserve were, and still are, used by WUT members for hunting, fishing, harvesting, and cultural and spiritual practices[1][8]. The rights to their land were never ceded or extinguished, instead the lands were taken by local colonial governments and settlers[9]. The Point Grondine Reserve on the north shore of Georgian Bay, which hosts the park, is the sparsely populated mainland portion of the Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory reserve system spanning from Collins Inlet to the mouth of the French River[1]. In 1996 this portion of their traditional territory was returned to them as part of a land settlement with the Ontario provincial government[10].

[i] A note on the Spelling of Wiikwemkoong: Wiikwemkoong is the traditional spelling used by the Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory to define their band. Though some affiliated organizations use the anglicized spelling of Wikwemikong. Examples include the Wikwemikong Trust and the Wikwemikong Department of Lands and Natural Resources. This case study uses the appropriate spelling of organization names, and uses Wiikwemkoong to refer to the community of Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory.

Tenure Arrangements

The Anishinaabe people of Wiikwemkoong have lived on Manitoulin Island and in the surrounding Killarney region since time immemorial[2], but today they still must work within the colonial tenure systems imposed upon them[11]. This is a common situation for First Nations, Inuit, and Metis groups across Canada[12]. The majority of reserve lands are managed under the land tenure regime established in the Indian Act (1985). Under the Indian Act bands have the right of exclusive use and occupation, while legal title rests with the Crown (or Government) holding the lands in trust for the band[13]. The Indian Act requires that reserve lands be used only in ways that benefit the whole community[14]. The land cannot be transferred to a different party; however bands have the ability to allot land as traditional holdings to band members or families to allow more exclusive use or to permit the building of dwellings[13]. Other communities have taken advantage of the First Nation Land Management Act (1999) to alter their specific reserve tenure system.

It is unclear what sort of land tenure system is in place for Point Grondine Park. PGP is located completely within the borders of the Point Grondine Reserve and is operated and governed by the WUT Chief and Council. PGP is intended to benefit the entire community by preserving traditional territory and providing employment and income. Given this, it is likely that PGP is currently being operated under the Indian Act tenure regime. This is further supported by the memorandums of understanding between them and provincial government bodies, such as Parks Ontario, for the independent operation of the park as well as the permanent and semi-permanent dwellings located on the north end of Mahzenazing Lake[5] which may be part of the “traditional holdings allotment”. It is also likely that the Wikwemikong Department of Land and Natural Resources (WDLNR) assists with the operation and maintenance of the park lands as it does for the surrounding reserve lands[15]. It is possible that PGP is also subject to provincial conservation and environmental protection standards and laws. The WDLNR website mentions and provides information on the First Nation Land Management Act, however when searching the FNLMA database Wiikwemkoong does not appear to be listed. The Chief and Council are working towards utilizing this Land Management Act to create the new A’ki Naaknigewin to benefit their community, but they are still is the consultation stage and have not yet submitted an application[15].

Institutional and Administrative Arrangements

Point Grondine Park is governed and operated by the community of Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory, primarily through the elected governing body of the Chief and Council[2]. As part of the Point Grondine Reserve 1996 land settlement, WUT was also awarded a $13,000,000 settlement for a boundary dispute over the reserve land[10]. The reserve land is governed by the Chief and Council, but the original compensation money, as well as any other land or assets, is held by the Wikwemikong Trust as trust property[10]. This trust property is jointly managed by Chief and Council and the Wikwemikong Trust. The current board of trustees is made up of WUT community members with backgrounds and qualifications ranging from Indigenous Studies to Law[10]. No other information was provided by Point Grondine on their park management and governance; however, in 2017 their park staff consisted of a Tourism Manager, an Interior Operations Leader, Product Development Officer, and a team of Trail Guardians and Guides[3]. It is also likely that the Wikwemikong Department of Lands and Natural Resources assists in the management and reporting processes as they are responsible for WUT’s various environmental operations including forest and shoreline management, land use planning, assessments, and environmental protection[16].

Affected Stakeholders

Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory

The primary affected stakeholders of this community forest are individual Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory members as well as the wider WUT community as a whole. WUT members are rights holders to the reserve land that the park sits on, and the wider community are stakeholders in the park[1][17][18]. WUT members use the park and other reserve lands for traditional land use activities such as food and medicine harvesting, hunting, and fishing. Some community members rely on the park for employment, while others may use it for recreation. The park and surrounding reserve lands are also used for community healing and welfare practices, such as the Outdoor Adventure Leadership Experience for WUT youth[19]. The entire WUT community is the largest stakeholder in Point Grondine Park as it operates on their reserve land and they benefit socially, culturally, and financially from its presence. Both the community as a whole and individual members have a high amount of relative power compared to other stakeholders, as they indirectly manage and shape the use of the park through band funds and governed by the elected Chief and Council.

Park Visitors

A secondary group of affected stakeholders is the user group of non-community visitors and tourists to the park. Though visitors to PGP are not an active stakeholder group, those that visit may have an emotional or lived connection to the space that they visit. This user group often uses PGP for similar recreational purposes and they do provide income and economic opportunities to the community, but they do not hold traditional user rights such as hunting on reserve land. They also possess the power to indirectly shape the built environment of the park as it strives to meet the demands of visitors[21]. This is apparent with the continuing goals of PGP’s development strategy[3]. Compared to the WUT community they have low relative power in this community forest landscape.

Interested Stakeholders

The Canadian Federal and Provincial Governments, and Associated Government Agencies

There are a number of interested stakeholders involved, or attempting to become involved, with Point Grondine Park. One of the most important interested stakeholders is the Canadian Federal Government. As WUT moves towards a shift in their tenure system through the First Nation Land Management Act the role of the government as a stakeholder in their reserve land enterprises will diminish[15]. But until such time the provisions under the Indian Act still remain in place, and as long as the Federal Government holds the legal title to the land in trust for the band, the Federal Government has the highest relative power among the other stakeholders. Point Grondine Park also currently relies on government funding and grants to support its development goals[1][21]. Another governmental stakeholder is the provincial government agency, Ontario Parks, specifically Killarney Provincial Park. Located in the same area, Ontario Parks and Point Grondine Park have had an ongoing, mutually beneficial, relationship since 2012. In 2016 a Memorandum of Understanding was signed to formalize this relationship[22]. In exchange for help with educational and Indigenous programming, Killarney Provincial Park provides training, certification, park management planning, and accommodation for Point Grondine Park staff[21]. This gives Ontario Parks a fair amount of relative power in terms of a relationship and key assistance that PGP relies upon, but they have no land use or decision making powers as control still rests with WUT.

The Canadian Biosphere Reserve Association - The Georgian Bay Biosphere Reserve Association

A stakeholder that is attempting to become involved in Point Grondine Park is the Canadian Biosphere Reserve Association, specifically the Georgian Bay Biosphere Reserve Association. It is a charitable organization working towards environmental protection and the preservation of ecologically important areas. Attempts have been made by this organization to incorporate Point Grondine Park into their conservation initiatives as an Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area (IPCA)[5]. Though, as of 2018, these attempts have been unsuccessful with little interest shown by WUT. This was possibly due to the poor timing of their communications, or because the organization lacked a strong relationship with the First Nation[5]. Other concerns about this organization’s involvement with local Indigenous groups have centred around issues such as: concerns about partnership given the federal government’s role on protecting biodiversity on Indigenous lands; requirements of the process at the community level; the balance between biodiversity investment and the development needs of the community; the timing of this activity as it relates to land management and self-governance processes; and the imbalance between required effort and the amount of quality land available[5][23]. Because of the lack of relationship and the issues mentioned, this interested stakeholder has very little power at present, though that may change in the future should it be decided that Point Grondine Park becomes an IPCA.

Other Interested Stakeholders

Other partnerships with interested parties include local hospitality businesses, such as Killarney Mountain Lodge, and tourism boards such as Northeastern Ontario Tourism and the Aboriginal Tourism Association of Canada[3].

Aims and Intentions

The park was originally established with the aim of protecting traditional land from degradation through future resource extraction[2]. It was important to protect this land due to its important cultural, historical, and spiritual significance to the WUT community[8]. It was also important that this land be held so that community members could still access it for traditional land uses[2][17][24]. Of increasing importance has been the aim of establishing a sustainable tourism industry for the WUT community, providing employment opportunities for community members and youth[2][22][21]. The intention to provide educational opportunities for visitors centred on Indigenous land use practices, culture, and history has been successful and has been met wide acclaim[1]. Generally Point Grondine Park, as a community forest endeavour, has been quite successful. Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory has successfully met their goals of protecting a large portion of their reserve territory, creating a viable tourism business for their community, and safeguarding the traditional user rights of their community members. The success of which is plainly illustrated in their future development goals and the exponential increase of visitors to the park, with a 200% increase from 2019 to 2020[1].

Issues

Due to an unfortunate lack of responses from interviewees and no evidence of issues facing Point Grondine Park specifically, to be found in the literature, it seems that the fact that this is an Indigenous owned-and-operated park established by the community on their own reserve land has mitigated many of the issues present in other community forest initiatives throughout Canada. However there are two important issues that may impact the wider WUT community, and the indirect effects on Point Grondine Park may be significant. The first of these possible issues is the ongoing process to change the land tenure system[11] that WUT operates under through the First Nation Land Management Act and their self-developed A’ki Naaknigewin system[15]. This is an ongoing process, and it is still unclear what the final results may be. But generally speaking this change would mean less government control of the reserve land, and a changing tenure system which could have adverse consequences on Wiikwemkoong’s land management practices[25][26].

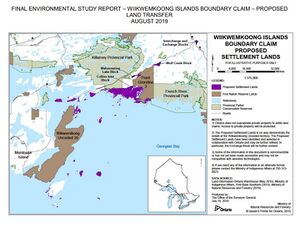

The second major issue which, although it is not directly related, may impact Point Grondine Park is the ongoing Wiikwemkoong Islands Boundary Claim. This land claim is centred on the islands off the eastern shore of Manitoulin Island to which WUT’s rights have never been extinguished through treaty or agreement[28]. The provincial government has proposed settlement lands which would transfer uninhabited crown land in place of currently settled and privatized land[9]. Some of the crown lands in question are adjacent to Point Grondine Park and have already been slated for Provincial Park development for several decades. This has caused concerns with many locals and non-Indigenous community organizations, such as the Georgian Bay Association, who cite a host of reasons including loss of recreation access rights, property value decreases, environmental degradation, and the loss of their power in crown land decision making processes[29]. Though Wiikwemkoong has stated that it wishes to preserve the natural environment of the transferred lands and plans to include the establishment of campsites or parks with Point Grondine Park cited as the preferred example[9] these associations are calling for the government to mandate that a park be created on the transferred lands[29]. If this issue is not handled effectively then it may result in tensions and community conflict between Wiikwemkoong and the surrounding non-Indigenous population. These conflicts could jeopardize the success of Point Grondine Park and the future of Indigenous owned parks as community forest spaces.

Governance and Power

At the community level the governance of Point Grondine Park is controlled through the Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory Chief and Council. The assets of the land and financial capital are held by the Wikwemikong Trust for the benefit of the community. Given that the Chief and Council are democratically elected by WUT members and the Trust assists in management it would appear that the governance of Point Grondine Park is in line with community goals and values[30]. In terms of power the actors with the most overarching power are the provincial and federal governments[25][13]. These are followed by the Wiikwemikong community and leaders, who hold a high amount of power but are at present still beholden to the decisions of government. Following the community the next more powerful social actors are the local businesses, non-WUT community, parks such as Killarney Provincial Park, environmental NGO’s, and tourism boards who typically work in partnership with PGP[3]. Partnerships with external organizations are of a mutually beneficial nature, whilst limiting the power of those external organizations to influence the operation of the park. However, given that true title and tenure still rests outside of the community (i.e. with the federal government) the power the community holds is still limited[31]. Some may argue that the involvement of the government in the decision making process prevents degradation and poor management. But the system currently in place also represents a lack of trust between stakeholders and a stifling of Indigenous sovereignty[17][18].

Recommendations for the Future

Point Grondine Park is an unprecedented example of an Indigenous owned and operated park which was realized by the tireless efforts of the Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory community. So far the park has met with success as indicated by their plans for further development to meet increasing visitor demand, including a solar-powered eco resort and a new 61 site campground[1]. Wiikwemkoong has established a sustainable tourism enterprise which provides employment for the community, educational opportunities for the public, and which does not infringe on the traditional user rights of the Wiikwemkoong Anishinabek[1][2]. Point Grondine Park is a case study in Indigenous-led community forestry which has the potential to be replicated throughout Canada, given that other reserve lands have the requisite natural capital to do so.

However, as Point Grondine Park and the practice of Indigenous community forestry moves forward for herein are presented two final recommendations to all actors and stakeholders involved:

- The current land tenure system for First Nations Reserves needs to accommodate community forest enterprises such as this, or else Wiikwemkoong must secure a tenure system through other means that allows them to exercise sovereignty over the traditional lands they have access to.

- It is important that all actors approach land use, land transfer, and land settlement decisions with clear communication and understanding so as to avoid tensions between Indigenous and local settler communities. But also approach them in such a way that builds trust, relationships, and does not impinge upon the sovereign rights of First Nations groups.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Davis, H. G. (2021, June 11). Point Grondine Park, Ontario: An Indigenous-owned park in Northern Ontario offers an education for all ages. The Globe and Mail .

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Point Grondine Park. (2021). Retrieved September 2021 , from Point Grondine Park : https://www.grondinepark.com/

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Point Grondine Park . (2017). Point Grondine Park Presentation . Canada: Point Grondine Park .

- ↑ Point Grondine Park. (2021). Retrieved September 2021 , from Point Grondine Park : https://www.grondinepark.com/

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Canadian Biosphere Reserves Association. (2018 ). CBRA'S CANADA TARGET 1 PILOT PROJECT: INTERIM PROGRESS REPORT DECEMBER 2018. CBRA .

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ministry of Northern Development, Mines, Natural Resources and Forestry. (2021, June 2). Forest Regions. Retrieved from Ontario: https://www.ontario.ca/page/forest-regions

- ↑ Moodie, J. (2014, November 08). Pointing the way to the coast ; ACCENT: Grondine Park paths form first leg in epic Georgian Bay trail. The Sudbury Sun, p. A.1.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Jacklin, K. (2007 ). STRENGTH IN ADVERSITY: COMMUNITY HEALTH AND HEALING IN WIKWEMIKONG. Hamilton : McMaster University .

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Ministry of Indigenous Affairs. (2019). Transfer of Crown Land to Contribute to the Settlement of the Wiikwemkoong Islands Boundary Claim: Environmental Study Report. Ministry of Indigenous Affairs.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Wikwemikong Trust. (2021). About. Retrieved December 3, 2021, from Wikwemikong Trust: Point Grondine Settlement : https://wikwemikongtrust.com/about

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 King, G. (2019, October 9). Forest Tenure in Ontario: Indigenous Participation. Government of Ontario .

- ↑ Mills, P. D. (n.d.). First Nations Right to Timber with respect to the Management of Lands for Hunting, Fishing & Livelihood, and Housing: Case Law Study. The National Aboriginal Forestry Association.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Aragon, F. M., & Kessler, A. (2018, November). Property rights on First Nations’ reserve land.

- ↑ Government of Canada . (1985 ). The Indian Act . Ottawa, Canada: Government of Canada .

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory. (2018). Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory A’ki Miinwa Enoodewiziimgak Genwendgik Naaknigewin 2nd Draft . Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory .

- ↑ Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory. (n.d.). Wiikwemkoong A’Ki Miinwaa Enoodewziimgak Genwendgik. Retrieved from https://wiikwemkoong.ca/administration/lands-and-natural-resources/

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Antoh, A. A. (2021). Pro Indigenous Community Forestry Policy: A Solution. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal , 341-345.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Lawler , J. H., & Bullock , R. C. (2017). A Case for Indigenous Community Forestry. Journal of Forestry, 117-125.

- ↑ Usuba , K., Russell, J., Ritchie , S. D., Mishibinijima, D., Wabano, M. J., Enosse , L., et al. (2019). Evaluating the Outdoor Adventure Leadership Experience (OALE) program using the Aboriginal Children’s Health and Well-being Measure (ACHWM©). Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education , 187-197.

- ↑ Point Grondine Park. (2021). Retrieved September 2021 , from Point Grondine Park : https://www.grondinepark.com/

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Burridge, R. (2014, May 14). Wiky to open eco-adventure park at Point Grondine territory: New park, trails and campground will be part of Georgian Bay Coastal Trail. The Manitoulin Expositor , p. 3.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Anishinabek News. (2016, May 10). Killarney Provincial Park to sign MOU with Point Grondine Park at Trails Symposium. Anishinabek News .

- ↑ Plotkin, R. (2018 ). Tribal Parks and Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas: Lessons Learned from B.C. Examples. Vancouver : David Suzuki Foundation .

- ↑ Berkes , F., & Davidson-Hunt , I. J. (2006). Biodiversity, traditional management systems, and cultural landscapes: examples from the boreal forest of Canada. Oxford: UNESCO - Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Anderson, D., & Flynn , A. (2021). Indigenous-Municipal Legal and Governance Relationships. IMFG Papers on Municipal Finance and Governance, 1-31.

- ↑ Baxter , J., & Trebilcock, M. (2009). "Formalizing" Land Tenure in First Nations: . Indigenous Law Journal , 45-122.

- ↑ Ministry of Indigenous Affairs. (2019). Transfer of Crown Land to Contribute to the Settlement of the Wiikwemkoong Islands Boundary Claim: Environmental Study Report. Ministry of Indigenous Affairs.

- ↑ Ontario Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs . (2015 ). Fact Sheet: Wiikwemkoong Islands Boundary Claim Negotiations . Government of Ontario .

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 GBA Board. (n.d.). Wiikwemkoong Islands Boundary Claim Final ESR – Response by the Georgian Bay Association with Supporting Documentation to Part II Order Request. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Georgian Bay Association.

- ↑ Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory. (2014). Wiikwemkoong Gchi-Naaknigewin. Canada: Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory.

- ↑ Radu, I. (2018). Land for Healing: Developing a First Nations Land-based Service Delivery Model . Bothwell, Ontario: Thunderbird Partnership Foundation.