Documentation:Guide to Teaching for New Faculty at UBC/Resource 1: How People Learn

Education is, not a preparation for life; education is life itself.

- Dewey

In this section, we will look at how people learn and some important concepts that will help you better understand the educational process, and then we will consider the implications of this for teaching.

Most instructors dream of imparting important, enduring knowledge to their learners, and hope that their students become self-motivated, expert problem-solvers with a sophisticated world-view. We often fall short of these dreams in courses crammed with content, classrooms designed for lecturing, and contexts that sometime quietly and sometimes overtly support the status quo. At the beginning of our teaching careers, we often dwell on our role as instructor with little regard for what is going on in students’ heads. It is important to remind ourselves that a high quality learning experience depends on a change in student thinking, and not necessarily on the instructor believing s/he “taught well.”

One of the most elegant explanations of “How People Learn” is provided by Bransford (editor) in the recent book: How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School. “How People Learn” is both a simple summary of some recent research in the cognitive sciences and an argument for how teaching should be done (Edelmean, 2003). The book provides educators with an excellent framework for understanding the science of learning. We have provided some highlights from the book for your convenience.

Knowledge Constructed not Transmitted

The current popular view of instruction has adopted many of the tenets of constructivism. Constructivism is an educational theory that espouses that learners construct knowledge and meaning from their experiences.

One of the hallmarks of the new science of learning is its emphasis on learning with understanding.

- (Bransford, 2003, p.8)

Social constructivism further espouses that learners needs to arrive at their version of the truth, influenced by their background, culture or embedded worldview. “This doesn’t mean that students are encouraged to believe what ever they want, rather that their truths need to be codeveloped with their social community by respecting, incorporating, modifying, adopting, and discarding information as appropriate. “ (Wikipedia)

The guiding principles of constructivism are:

- Knowledge is constructed, not transmitted

- Prior knowledge impacts learning

- Building knowledge requires effort and purposeful activity

Implications for Teaching

“If there is one thing I would like to go back and change about my teaching it would be that I did not take enough time to find out what my students knew about a topic before launching into it. To assume that they had no knowledge or beliefs about the topic was, frankly, absurd.”

- — Gary Poole, Former Director of UBC Centre for Teaching, Learning and Technology

We must access and leverage students’ prior knowledge

Students bring their understanding of the world around them to the educational process. As teachers, we need to understand the mental models that our students use to perceive the world. Understanding our learners is the typical starting point for meaningful instruction.

Sometimes new information can be neatly “assimilated” into students’ existing understanding of the world, and sometimes their worldview needs to shift or “accommodate” the new information. The Swiss educational theorist Jean Piaget (1896-1980) first espoused the idea that learners either assimilate new information or shift their way of thinking to accommodate the new information. The process of shifting one’s framework of thinking can be a difficult and uncomfortable one for learners. They may need to abandon their previously held worldviews to accommodate the new information.

Piaget’s educational theory conceives that intellectual development as occurring in 4 periods. A Sensorimotor Stage early in life, as we get to know our environment. A Preoperational Stage as we gain language and start to interact with the world in a deeper way. We then move to a Concrete Operational Stage characterized by logical thinking with limited abstraction. Finally, people move to a Formal Operational Stage where abstract thinking and enjoying abstract thought becomes the norm. It had originally been conceived that people moved into the last stage, Formal Operation, by age 12. There is now considerable evidence that many adults live their entire lives at the Concrete Operational Stage.

When our student come to us, they are likely in the Concrete Operational Stage. When faced with abstraction, creativity, and ambiguity they often react by memorization and are unable to use this material to solve novel problems. These students will attempt to succeed by rote memorization, partial credit, and repeating courses. They will shy way from open-ended problems and are often unable to learn from their mistakes. If you teach a course that requires higher level thinking or complex novel problem solving, and a student claims it is all memorization, you have to wonder what stage they are at.

However, there is a considerable amount of literature in education that reports that students will often revert to their original misconceptions after instruction, even when the new information is clearly in conflict with their existing understanding, and the new information has been successfully retrieved for testing purposes.

We must give students opportunities to actively construct their own meaning

Many educators believe that knowledge cannot be transmitted; only information can be transmitted. When we instructors transmit information to our students we must also create opportunities for our students to individually create meaning from the information. The students need opportunities to actively work with the new information in meaningful ways to turn it into knowledge. Real, authentic problem solving can give students the opportunities to use new information and fine-tune their understanding. When students problem solve with their peers they can often progress more quickly than when they work alone or interact with an expert. Working with peers who are at a similar or slightly higher level of understanding can speed a student’s progress.

The positive effect of a task that is slightly more challenging than one’s current abilities, and progress that is hastened by the support of fellow learners has been described by Lev Vygotsky as the Zone of Proximal Development. Vygotsky also describes a process known as scaffolding, where the instructor can provide appropriate level of instructional challenge and guidance to maximize students’ progress on a particular learning task, and fade from the instructional process as student mastery increases.

The concepts of scaffolding and fading are cornerstones of many Guided Inquiry styles of learning (POGIL-Process Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning; PBL-Problem Based Learning). Fading is the concept that instructors may need to provide more guidance early in the student learning process and then fade as the students’ abilities increase. However, Guided Inquiry learning has received some bad press from Kirschner, Sweller and Clark and others. They took the provocative view that educators were suggesting inquiry without any guidance and not surprisingly, found that this approach is ineffective. Most reasonable educators promote guided inquiry learning, where the amount of guidance varies on the task and learner development.

Suggested Reading

- Bransford, John, D., Ann L. Brown, Rodney R. Cocking (eds.) How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition. National Academies Press, 2000.

Permalink

Permalink

Some Other Educational Ideas Worth Knowing

Bloom’s Taxonomy

In 1956, Benjamin Bloom developed an important taxonomy of educational objectives in three domains (Cognitive, Affective and Psychomotor) to help with preparation of comprehensive examinations at the University of Chicago graduate school. The taxonomy has since become one of the cornerstones of North American education, as it helps educators use common language around learning goals, and helps individual practitioners articulate the educational possibilities within a particular piece of instruction, course, or program.

In the cognitive domain there are six Bloom’s levels; the lowest being Remembering, moving through Understanding, to Applying, to Analyzing, to Evaluating, and finally to Creating. When designing learning experiences, it can be helpful to use Bloom’s levels to help you visualize and plan students cognitive progress as they move through your course. The Bloom’s levels can be mapped to various verbs and these verbs can be used to generate learning objectives and create test questions that correspond to different Bloom’s levels.

| Remembering | Understanding | Applying | Analyzing | Creating/Evaluating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| know

define memorize list recall name relate write label state |

restate

discuss describe recognize explain identify locate summarize paraphrase illustrate |

use

translate interpret apply employ demonstrate dramatize practice illustrate operate compute construct |

distinguish

analyze differentiate calculate experiment compare contrast criticize solve examine categorize |

compose

plan propose design assemble construct create design organize manage recommend |

judge

appraise evaluate compare value select choose assess estimate measure hypothesize |

Perry's Model of Cognitive Development

There are many cognitive development frameworks (Perry, Blenkey, Baxter Magolda, Kuhn) that all posit that students are on a development trajectory from simple to complex thinking, from concrete to abstract, non-reflective to reflective where their thinking progresses from a black/white right/wrong absolutist thinking to a more robust evaluative view of our uncertain world. All the frameworks have limitations but can be useful to help us consider what might be going on in our student’s heads, so we can better serve them.

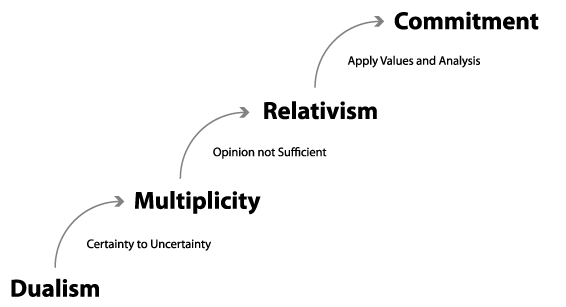

Perry developed one of the most popular frameworks. William Perry (1970) studied the development of white, male students at Harvard University. He developed a model that described the stages that students pass through in their cognitive development. He identified 9 distinct stages as students move from a dualist view (black and white, right and wrong) to a relativistic view (other opinion exist, ambiguity exist, different position have strength and weaknesses). Students will ultimately move to a commitment position where they can weigh the evidence and commit to a reasonable position.

| Dualist

Knowledge is certain Black/White Right/Wrong Authority is source of truth |

There can be considerable student discomfort as they pass through the different stages and considerable discomfort and difficulty with assignment that require thinking at a higher stage than they are at. Students arriving at University often

still have a very dualist view of the world. There are clear rights and clear wrongs. The instructor is the authoritative source of the “right” answer. When the instructor introduces ambiguity, students in the dualist view often lose confidence in the authority and claim that assignment wordings are vague and assessment is too subjective. Conflicts are possible since the authority does not know the “truth”. Students eventually start to become aware of other perspectives, but tend to cling to their dualist view of the world. Is my instructor playing games with me “why don’t they just tell me the right answer”. Students at this stage tend to dislike open-ended problems. |

| |

| Relativist

Uncertainty exists Truth is subjective |

Eventually the student may realize that the instructor is not playing games and that some areas of knowledge are fuzzier than others. There is still difficulty at this stage, since the authority doesn’t know the “right” answer – how could they possible fairly evaluate my work? Students then move to understanding there is legitimate uncertainty and a diversity of perspectives, but are still uncomfortable. A quote from Wankat and Oreovicz is enlightening “Everyone has a right to their opinion is obviously wonderful position to fight authority“. |

| |

| Commitment

Choices require analysis of sometimes imperfect data |

Once the student truly embraces relativism, they realize that “all opinions are not equal” and evidence can be used to develop and support different positions. Another quote from Wankat and Oreovicz is helpful here – “a good instructor acts as a source of expertise…the professor helps students become more adept at forming rules to develop reasonable and likely solutions…”

Student will eventually commit to one position being better then others based on “weighing of the evidence”. This can feel risky to the student. The instructor should take step to ensure the safety of the learning environment to help the students have the courage to make these commitments. |

Implications for Teaching – Perry’s Framework (based on Nelson adaption)

The Perry framework (Nelson Adaption) can help you better understand your students responses to certain types of tasks, and can be used to help you design task that help with the transition from one stage of cognitive development to the next.

Transition: Dualism to Multiplicity

To aid students in this transition, you must challenge their dualistic beliefs and make students aware of ambiguity and uncertainty. Upsetting the student’s equilibrium can be hazardous to a faculty member’s mental health. Some students will vigorously resist and complain about this shift. It is very important to demonstrate (and demonstrate often) that the dualist view of the world is invalid.

You need to design activities that force students to confront differing views. Thoma (1993) recommends paired reading summaries so students can explore opposing points of view, and historical overviews that highlight the ongoing development of knowledge. Team activities can help students with this uncomfortable transition.

Transition: Opinion is Insufficient

At this stage student need to come to realize all opinions are not equal. We need to help them develop criteria to evaluate differing positions. The lost of absolutely certainty can lead students to believe that the subject is soft or inexact, since no right answer exists. Helping the students developing methodologies and criteria to discriminate between different positions is the goal of this stage.

At this stage, paired readings can again be used, but students can be pushed to go beyond summarization to analysis and evaluation. Team preparation of these kinds of analysis can foster metacognition (how do I know I know) and the development of a richer social consensus built through dialogue. Activities that require students or teams of students to take and defend a position will foster this transition.

Transition: Merging Values and Analysis to develop Logical Criteria

At this stage, discipline specific approaches to analysis are often introduced. Students must come to realize that just as there are different positions with strength and weaknesses, there are different analysis methodologies with different strengths and weakness. Students can view this stage as an academic game that must be played to do well to excel in the course. This transition is often NOT achieved in the undergraduate years (Thoma, 1993).

Transition: Contextual Appropriate Decisions

In the final stage, students need to accept the uncertainty of both knowledge, and methods of analysis. They realize that their values and sound judgment are needed to make “good” decision with imperfect data and analysis methods.

Learning Styles: “A Useful Fiction”?

We have all likely heard someone describe him/herself as a “visual” learner – someone who learns best from pictures, diagrams etc. Learning styles and thinking about them evolved when educators noticed that different forms of instruction seemed to work better for different learners. You may think you have a “preferred” learning style, but we all need to learn in a variety of ways (not just our preferred) to acquire deep, enduring understandings. The literature about learning styles has found that the they are not a valid construct, and do not provide reliable information on learners preferences, strengths and weaknesses. (Experiments like providing visual resource to visual learner having no effect) As a result, many educators find learning styles a contentious subject. The power of learning styles may be in the thinking/reflecting/ understanding they can bring to your planning as you design instructional activities.

There are more than 80 types of learning styles inventories (inventories are typically questionnaires or structured tasks that can be used to categorize the learner as a certain style). In 1993 Howard Gardner, who developed the “multiple intelligences” learning styles inventory, described his inventory as a “useful fiction.”

Kolb’s Learning Cycle

One of the most popular and useful learning styles inventories was developed by David Kolb (1983). His model, the Kolb’s Learning Cycle, arranges learners on two continuums; the first categorizes a learner’s preferred approach to a task, and the second, how a learner prefers to engage in the task. The first continuum on task approach ranges from learners who prefer “doing” (active experimentation label) to learners who prefer “watching” (reflective observation label). The second continuum on experience preference ranges from learners who prefer the “concrete” (concrete experience label) to learners who prefer “thinking” (abstract conceptualization label). Depending on your aggregate placement on these continuums, you can be described as a Converging or Diverging learner or an Assimilating or Accommodating learner.

The Kolb’s Learning Cycle provides an instructional frame showing how instructors and learners likely need to “cycle” through a variety of approaches to a given learning task to develop a deep, enduring understanding. If you were to design a learning experience using the Kolb Cycle, you might give your learners the opportunity to gain some “concrete experience”, then do some “reflection” on the experience, followed by a chance to “abstract” meaning from the experience, and finally the occasion to “actively test” and refine their new understandings.