Course:MGMT405 2022W2/Case-2iii

Petrobras: An Intricate Web of Political and Corporate Racketeering

| |

|---|---|

| Traded as | NYSE: PBR, PBRA

B3 Level 2: PETR3, PETR4 |

| Revenue | $83.9B (2022) |

| Standard Industrial Classification | 1311 - Crude Petroleum & Natural Gas |

| CEO | Jean Paul Prates (Jan 26, 2023 - )

Caio Mário Paes de Andrade (June 28, 2022 - ) |

| Founded | October 3, 1953, Brazil |

| Founders | Getúlio Vargas, Federal government of Brazil |

| Headquarters | Avenida República do Chile 65, 20031-912,

Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil |

| Performance Areas | Oil and Gas Exploration and Production, Refining,

Supply of Natural Gas, Generation of Electric Energy, Transportation and Trade |

| Website | http://www.petrobras.com.br/ |

Background and Growth

Petrobras, an abbreviation of Petróleo Brasileiro S.A, was founded in 1953 as a state-owned monopoly engaged in the oil and gas sector. In 1997, the Brazilian government ended the company's monopoly, opening the industry to international competition [1]. Today, Petrobras is a publicly traded corporation which is majority-owned by the Federal Government, holding 50.26% of common shares[2].

During 2008, when the prices of commodities rose by an average of approximately 75%[3], Petrobras was ranked the world’s sixth-largest company, with a net worth of $287 billion, surpassing Microsoft[4]. At this time, it represented 10% of the Brazilian GDP [5] and was listed among the top 50 companies for transparency levels worldwide [6]. Petrobras' prosperity was fueled by Brazilian growth in crude oil production: in 1953 the country was producing an average of 2,700 barrels a day. In 2010, production skyrocketed to 2,000,000 barrels daily. [1] Petrobras was on track to achieve Brazilian self-sufficiency in crude oil [6]. This growth was sustained by the company’s discovery of a large deep-water oil field off the coast of Rio de Janeiro [1] that helped the company develop the offshore technologies and capabilities necessary to reduce production lead time from 4-6 years to only four months [7]. Today, most of Petrobras’ reserves are in offshore fields nestled in deep and ultra-deep waters [8].

Petrobras Scandal

Operation Car Wash

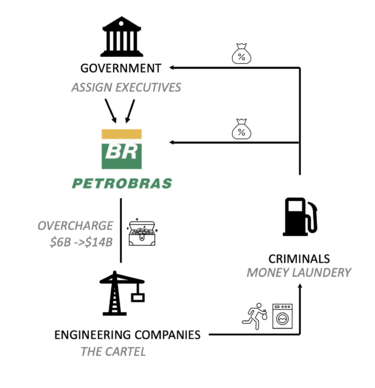

Although corruption in Petrobras started during the commodities boom in the early 2000s, prosecutors only scratched the tip of the iceberg in 2013, when Alberto Youssef was detained on a money laundering charge [9]. The beginning of the investigation was focused on black market money dealers who used small businesses, such as car washes, to launder illegal profits. This was the origin of the scandal’s name, dubbed “Operation Car Wash”[10]. Mr. Youssef had been previously arrested nine times [9], but spent little more than 15 months in prison due to plea agreements in exchange for reduced sentences. This time, Youssef expressed that “if I talk, the republic is going to fall”. After signing yet another plea agreement, he proceeded to list the names of the participants involved in what is known today as the biggest Brazilian investigation against corruption and money laundering to date. The "big break" in the investigation was the discovery of an email showcasing Youssef’s purchase of a Range Rover to Paulo Roberto Costa, Petrobras' director of refining and supply from 2004 to 2012. From that piece of evidence, police were able to arrest a key insider who was willing to cooperate, and their inspection into Petrobras began [5]. Between Costa and Youssef, evidence of corruption by Brazil’s wealthiest and most powerful individuals started unraveling[9], and prosecutors quickly realized that the case was “100 times bigger” than their original investigation[5].

According to the Federal Police and the Public Prosecution Office, Petrobras lost 140 billion Brazilian reais (approximately 35 billion USD at the time), equivalent to 2.5% of the country’s GDP, in a scheme involving construction companies, Petrobras employees, and politicians[11].

The oil and gas company spends more than USD$20 billion a year on construction projects to expand its capacity, relying on subcontractors to carry on such projects. Although companies have historically competed against each other in bidding for contracts[5], the investigation suggested that between 2003 and 2004[11], they organized themselves into a cartel and began collaborating [5]. At the beginning, there were nine construction companies involved, known as the “club of 9”. By 2006, the club expanded to 16 participants[11]. The cartel activity allowed firms to charge Petrobras “outrageous sums” due to the absence of a free market [9]. That can be clearly identified through an analysis of the Petrobras database, which outlines information on recent contracts. A paper by Barbosa and Spagnolo compared the value of contracts signed by the company’s main suppliers that were not part of the organized cartel with those signed by the most prominent cartel members. Although companies who were not members of the cartel supplied approximately 181 times the number of contracts as compared to cartel members in the same period, the total value of these contracts was equivalent, at 685 billion reais [11].

This scheme was only possible through the cooperation from a select group of Petrobras’ executives, who willingly turned a blind eye and were in turn rewarded with generous bribes[9]. The company who won the bidding process would distribute 1-5% of the value of a contract to Petrobras executives and to politicians through financial intermediaries[11], such as ghost corporations, who would make bribes resemble consulting fees. Some of it was also delivered in cash by Rafael Lopez, the money mule, who would hide up to five hundred thousand euros under his clothing. Aside from money, bribes would also be made with luxurious gifts, including Rolex watches, yachts and helicopters [5].

Inflated contracts that were the target of investigations include the purchase of an oil refinery in Pasadena, Texas, which offered "a first indication of the high level of corruption in Petrobras' activities" according to a prosecutor in Brazil's Federal Accounts Court[12]. The company paid USD$360 million for 50% ownership in the refinery, more than eight times what Astra Oil paid for the entire complex a year earlier. Due to further expenditures, including a legal dispute with Astra Oil where Petrobras purchased their remaining ownership, the company lost more that $580 million in this deal alone [13].

João Elek, who was appointed head of compliance after the scandal, believes that the company culture contributed to the corruption that took place. He suggested that for years, no one would question executives at Petrobras, even if they approved unusual or questionable deals[5].

Key Players

The Petrobras scandal was a complex web of corruption involving many different players from the worlds of politics, business, and organized crime. After thorough investigation by the police and the government, a large number of players were found to be participating in the large scheme of money laundering and corruption and were arrested starting November 2014 [14]. However, no one particular name could be found who could be blamed for the start of the scandal. The major key players were the Petrobras executives, politicians, and construction companies.

Petrobras Executives

Paulo Roberto Costa

Paulo Roberto Costa began his career at Petrobras in 1977, a year after graduating with a Mechanical Engineering degree from the Federal University of Paraná [15]. He was appointed as the Director of Refining and Supply at Petrobras in 2004, through the indication of a congressman. [16] Paulo was one of the first high-ranking Petrobras executives to be arrested in connection with the scandal. He was found guilty of corruption charges and later agreed to pay back $23 million[14]. Refer to Current Status and Lawsuits section for information on Costa's sentence.

Renato Duque

Renato Duque had a very similar professional journey to Paulo's. After graduating as an engineer he began working with Petrobras in 1978, and in his long tenure of 30 years, he was able to rise up to the rank of Director of Engineering and Services. His department was responsible for handling the majority of the firm’s investments which gave him excessive power to manipulate the money coming in and out. Prosecutors found transactions totaling approximately $21 million between international accounts that were under his management. These figures were far from his earnings at the time. Although he was detained for three weeks in the early phases of the operation, this particular evidence gave enough support for the prosecutors to issue an arrest warrant[17].

Pedro Barusco

Pedro José Barusco Filho was the Executive Manager of Engineering at Petrobras, working under the directorship of Renato Duque. As every Petrobras official started to spill the beans on the operation in an effort to save themselves, Pedro informed the officials that he started receiving payments from as early as 1997, and the payments started to grow as the Worker’s Party came in power, from 2004. He even stated in his deposition that the treasurer of Rousseff’s party received anywhere between the sums of $150 million to $200 million from 2003 to 2014. He informed the officials that everyone "got a piece of the pie", including himself, pledging to repay the public coffers $97 million in his plea deal[18].

Other Executives involved

Some other executives that were found to be active in this large web of corruption were: (1) Aldemir Bendine, former CEO of Petrobras who was accused of accepting bribes from construction company Odebrecht in exchange for awarding them contracts with Petrobras. According to prosecutors, Bendine asked for and received bribes totaling 3 million reais (approximately $950,000 at the time) from Odebrecht when he was CEO of Petrobras. The bribes were allegedly paid through an intermediary in exchange for contracts for the construction company. Bendine was charged with corruption, money laundering, and obstruction of justice[19]. (2) Nestor Cerveró - Former director of Petrobras' international division. He was accused of taking bribes from companies involved in Petrobras contracts and was sentenced to more than 12 years in prison[20]. (3) Jorge Zelada - Former director of Petrobras' international division. He was accused of receiving millions of dollars in bribes related to the construction of offshore drilling platforms[21].

Politicians

José Dirceu

José Dirceu de Oliveira e Silva was the Chief of Staff to President Lula from 2003-2005. José was arrested in a separate vote-buying scandal in 2014 that was connected to the first term of president Lula. The prosecutors of the ‘Operation Car Wash’ said that José was receiving payments from contractors while he was in office, profiting from it even during his time serving sentence. José was later found guilty of corruption and money laundering associated with the Petrobras scandal in 2017. He was also known to be the one responsible behind the hiring of two ex-Petrobras executives involved in the scandal, former refining and supply chief, Paulo Roberto Costa, and former head of engineering and services, Renato Duque [22]. Refer to Current Status and Lawsuits section for more information on Dirceu's sentence.

João Vaccari Neto

João Vaccari Neto was the treasurer of the Workers' Party from 2010 to 2015. Evidence collected from the plea deals that took place in the early stages of the operation facilitated prosecutors in charging and arresting Neto. He was found guilty for taking bribes in the form of campaign donations from oil field service companies. Duque, the Director of Engineering and Services at Petrobras was responsible for moving the money to Neto's accounts[23]. Duque and Neto also faced charges associated with money laundering and the operation of a cartel[24]. In 2015, João Vaccari Neto was found guilty of corruption and money laundering, and was found to take over $1 million in bribes[23].

Antonio Palocci

Antonio Palocci Filho was the Finance Minister of Brazil from January 2003- March 2006 to President Lula, and chief of staff to Dilma Rousseff for the first 6 months of 2011. It was alleged that Palocci worked with the construction firm Odebrecht to receive bribes up to the amount of $39.5 Million for the Worker’s Party between the years 2008 and 2013. In exchange Palocci offered the construction company bloated contracts with Petrobras. He was convicted of corruption and money laundering in the Petrobras scandal in 2018[25]. Refer to Current Status and Lawsuits section for information on Palocci's sentence.

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, commonly known as Lula, was the President of Brazil from 2003 to 2010 and a prominent member of the Worker's Party. He was implicated in the Petrobras scandal through the investigation of his ownership in a seaside luxury apartment, that had ties to a construction firm. He was accused of accepting a bribe of approximately 3.7 million reais ($1.1 million) from construction company OAS in exchange for a contract with Petrobras. Public prosecutor Dallagnol stated that Lula was "the conductor of this criminal orchestra", and the scheme was aimed at keeping the Worker's Party in power through illegal methods [26]. Lula denied his allegations, and his defense team argued that the evidence against him was circumstantial[14]. Refer to Current Status and Lawsuits section for more information on Lula's sentencing.

Construction Companies

A number of Brazilian construction companies were involved in the scandal, allegedly paying bribes in exchange for securing contracts with Petrobras. The "club of 16" was a group of construction companies accused of forming a cartel to rig bids on contracts with Petrobras, compensating executives and politicians with bribes. The major construction companies involved in the scandal were: Odebrecht, Andrade Gutierrez, Camargo Corrêa, OAS, UTC Engenharia, Queiroz Galvão, Mendes Júnior, Engevix, Galvão Engenharia, Iesa Óleo e Gás, Skanska, Promon Engenharia, GDK, Tomé Engenharia, Fidens Engenharia, SOG Óleo e Gás. These companies were collectively accused of paying billions of dollars in bribes in exchange for lucrative Petrobras contracts[11].

Odebrecht, the Leader of the Cartel

Odebrecht is the biggest firm and the ring leader of the cartel, winning a major contract to build Comperj. Petrobras paid at least $14 billion for the construction project, when it should have actually been charged $6 billion [27]. Odebrecht and its co-conspirators paid approximately USD $78 million in bribes to secure more than 100 projects in Angola, Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Mozambique, Panama, Peru, and Venezuela[28]. In 2016, Odebrecht confessed to corruption and paid USD$2.6bn in fines [29] and in 2019, it filed for bankruptcy protection, so that it could restructure 51 billion BRL ($13 billion) of debt[30]. Odebrecht changed its name to Novonor in 2020 in an attempt to repair its reputation[31].

Capital Market Players

Foreign Banks

Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) investigated more than a dozen Swiss banks in relation to the Petrobras scandal. A private Swiss bank Lugano-headquartered PKB found guilty of breaching money laundering rules in relation to the Petrobras scandal and paid CHF 1.3 million (USD $1.4 million) in illicitly gained assets [32]. In 2016, the regulator sanctioned BSI bank and Banque Heritage as well. The regulators have frozen around $800 million in assets stashed in Swiss accounts, and released some $190 million to the Brazilian authorities[33].

Key Stakeholders

Capital Market Stakeholders

Petrobras made an international debut through a public listing on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) on August 10, 2000, and Petrobras celebrated the world's largest share offering to date, which reached R$ 115 billion in 2010[34]. Soon after the revelation of fraudulent activities around Petrobras, the company's share price in Brazil plummeted by over 80% and the price of its American Depositary Shares (ADSs) on the NYSE by 78%[35]. The loss suffered by Petrobras investors who purchased the company's securities in the U.S. from January 22, 2010 to July 28, 2015 were resolved by the $3 billion settlement in 2018[35].

Petrobras’s 3.7 billion shares were once an economy booster to Brazil. In the three years before the revelation of corrupted business, Petrobras paid back an average annual dividend of £360m. Since the scandal, no dividends have been paid out up until 2021[36].

Product Market Stakeholders

Suppliers / Contractors

The contractors play a major role in the downfall of Petrobras. The construction companies colluded to determine the winners of each bid and the charging price for the services they rendered[37]. Six construction and engineering groups were sued by the Brazilian prosecutors for the damages caused around the Petrobras, seeking 4.47 billion reais ($1.55 billion) [38]. Refer to the Construction Companies section under Key Players to read more about the suppliers involved in the scandal.

Organizational Stakeholders

Employees

People from across the country relocated to Itaboraí to work on the construction of a petrochemical complex or to open local businesses around the construction site. When Petrobras had to cut spending, the employees and the community built around them had been hung out to dry and had no government to ask for help [39]. A study by Inter-union Department of Socio-Economic Studies (DIEESE) found that the operation car wash paralyzed construction projects and industry activities throughout Brazil. As a result, total of 4.4 million jobs were lost, of which were 1.1 million construction jobs[40].

Community Stakeholders

Community - Brazil Economy

The Petrobras scandal had a detrimental impact on the Brazilian economy and their fall rippled through Latin America. In 2015, this scandal led to a GDP per capita reduction from 12,071 in 2014 to 8,783 in 2015[41]. As one of the main contributors to the Brazilian economy, Petrobras spent more than $40 billion annually in capital investments. The chain reaction from the cessation of their big investments in infrastructure companies led to mass layoffs within the construction industry[43]. Comperj, a $1.3 billion fertilizer plant, and dozens of production and drilling ships, each costing hundreds of millions of dollars were put in jeopardy[43]. This plunged Brazil into one of the worst recessions it has faced in its last 25 years [44], losing more than 1% of its overall GDP [45]. On top of their economic and political emergency, due to the change in foreign investors' expectation in Brazil's foreseeable future, foreign direct investment, net inflows (BoP, current US$) reduced from 87.71 billion in 2014 to 64.74 billion in just one year [46]. This is reflected on the weakening of BRL:USD exchange rate.

Government

The government encouraged Petrobras to take on more debt which was eventually found to be funding the briberies and election campaigns[48] . Some well-known politicians were indicted or jailed due to their participation in the scandal.

The Petrobras scandal startled the increase in Brazil Government Debt (as % of Nominal GDP from monthly Government Debt and rolling sum of monthly Nominal GDP). In 2014 before the scandal, the debt was below 53%, rising up to more than 65% in 2016 and increasing steadily since[49].

Current Status and Lawsuits

Petrobras Charged by SEC for Misleading Investors

On September 27th 2018, Petrobras was charged with misleading U.S. investors by publishing fraudulent financial statements by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The SEC came to a non-prosecution agreement[50] which has led to a total payout of $933 million in disgorgement and prejudgment interest and an $853 million penalty. These charges came to fruition as Brazilian investigators uncovered that Petrobras' financial statements were covering up a massive bribery and bid-rigging scheme. The SEC order also found that the contractors and suppliers working with Petrobras were collaborating with top executives to inflate the cost of the infrastructure projects by billions of dollars. These contractors and suppliers were also found to giving kick backs to the top executives of Petrobras, who used the money to make illegal payments to Brazilian politicians, recording these instead as expenditures to acquire and improve assets, resulting in an overstatement of approximately $2.5 billion in assets[51].

Class-Lawsuit Filed by Petrobras Investors

In January and February 2018, Petrobras settled with the suing investors for $2.95 billion[52]. Along with this lawsuit, the investors also settled with PwC for another $50 million, totaling the class-action lawsuits for the fraud related to Petrobras at $3 billion. This lawsuit is the biggest payouts in US history by a foreign entity[53]. On the first part of the settlement, the corporate counsel stated "if any general counsel out there are still letting their companies sleepwalk through compliance programs, Wednesday’s $2.95 billion class action settlement with the Brazilian oil company Petrobras should smack them wide awake." This case has been considered to have set the stepping stones for future in class-actions for corporate fraud[52].

Dutch Class-Action Lawsuit

In 2017, a Dutch investor began legal proceedings against Petrobras which has now been joined by investors outside of the US who invested on the Brazil and Netherlands stock exchange[54]. The investors in the lawsuit claim that Petrobras made false and misleading statements about its financial condition, which caused them to invest in the company at artificially inflated prices. This took place after the SEC fines and US investors class-action lawsuit against Petrobras. This result of this lawsuit is still uncertain[55].

Criminal Charges

As of May 2019, there have been 90 criminal accusations against 429 different individuals, including 244 convictions among 159 people in connection with the Petrobras scandal[56]. These individuals include former executives of Petrobras, politicians, and business leaders who were involved in a bribery and kickback scheme that involved the awarding of contracts to construction companies in exchange for bribes [56]. The biggest names in relation to the Operation Car Wash that were arrested are as follows:

Marcelo Odebrecht

- The former CEO of Odebrecht, one of the largest construction companies in Brazil, was arrested in 2015 and sentenced to 19 years in prison for corruption and money laundering. He was later released in 2017 after striking a plea deal with prosecutors[57].

Sergio Cabral

- The former governor of Rio de Janeiro was arrested in 2016 and sentenced to 14 years and 2 months in prison for corruption and money laundering. Cabral was accused of receiving millions of dollars in bribes from construction companies, including Odebrecht[58].

Eduardo Cunha

- The former speaker of the lower house of Brazil's Congress was arrested in 2016 and sentenced to over 15 years in prison for corruption and money laundering. Cunha was accused of taking bribes in connection with Petrobras contracts and using his political power to obstruct the investigation[59].

Jose Dirceu

- The former chief of staff to Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva was arrested in 2015 and sentenced to 23 years in prison for corruption and money laundering. Dirceu was accused of taking bribes in connection with Petrobras contracts and using his political power to facilitate the scheme[60].

Paulo Roberto Costa

- The former director of refining and supply at Petrobras was arrested in 2014 and sentenced to 7 years and 6 months in prison for corruption and money laundering. Costa was accused of taking bribes from construction companies in exchange for contracts with Petrobras[61]. However, through plea bargains and his time spent in detention, Costa only served one year of house arrest [62]

Antonio Palocci

- The former finance minister of Brazil was arrested in 2016 and sentenced to over 12 years in prison for corruption and money laundering. Palocci was accused of taking bribes in connection with Petrobras contracts and using his political influence to benefit the construction companies involved in the scheme[63].

President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva

- The President was convicted on charges of corruption and money laundering in connection with the Petrobras scandal. He was sentenced to 9 years in prison, but he remained free while his case was under appeal. In 2019, his sentence was increased to 12 years and one month, and he was ordered to return to prison to serve his sentence. Later, in November 2019, Lula was released from prison after serving 580 days, when the country's Supreme Court issued a ruling that could lead to the release of thousands of prisoners who had been jailed on corruption charges. In March 2021, Lula's conviction was overturned by Brazil's Supreme Court, clearing the way for him to run for office again[64]. Lula has won the 2022 presidential election, securing 50.8% of the votes [65].

Post Scandal Effects

Impact on Brazil’s Economy

Refer to community stakeholders section.

Influence on New Legislation

Here are the ways in which the Petrobras scandal influenced legislation in Brazil:

- Anti-corruption legislation: The scandal led to the introduction of several pieces of anti-corruption legislation which was enacted in 2014. This law established strict liability for companies that engage in corrupt activities and created incentives for companies to self-report and cooperate with authorities[66].

- Campaign finance reform: The scandal highlighted the role of campaign finance in corrupt practices, leading to calls for campaign finance reform. In 2015, Brazil introduced new laws to regulate campaign financing and limit the influence of money in politics[67].

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Petrobras Brazilian Corporation". (n.d). Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Petrobras. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "Shareholding Structure". Petrobras: Shareholder Structure. (n.d). Retrieved Retrieved from https://www.investidorpetrobras.com.br/en/overview/shareholding-structure/. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ Spatafora, N., Irina, T. (n.d). "Commodity terms of trade: The history of booms and busts". World Trade Organization. Retrieved from https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/wtr10_forum_e/wtr10_13july10_e.htm. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Idoeta, Paula Adamo (April 9, 2014). "Brazil's energy giant Petrobras is mired in controversy". BBC. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/business-26938615. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Segal, David (August 7, 2015). "Petrobras Oil Scandal Leaves Brazilians Lamenting a Lost Dream". New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/09/business/international/effects-of-petrobras-scandal-leave-brazilians-lamenting-a-lost-dream.html. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 6.0 6.1 Viswanatham, R. (June 11, 2015). "The Rise and Fall of Petrobras". Gateway House. Retrieved from https://www.gatewayhouse.in/the-rise-and-fall-of-petrobras/#_ednref6. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Our Activities / Campos Basin". Petrobras. Retrieved from https://petrobras.com.br/en/our-activities/main-operations/basins/campos-basin.htm. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Main Operations/ Basins". Petrobras. Retrieved from https://petrobras.com.br/en/our-activities/main-operations/basins/. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Beauchamp, Zack (March 18, 2016). "Brazil's Petrobras scandal, explained". Vox. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/2016/3/18/11260924/petrobras-brazil. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Watts, Jonathan (June 1, 2017). "Operation Car Wash: Is this the biggest corruption scandal in history?". The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jun/01/brazil-operation-car-wash-is-this-the-biggest-corruption-scandal-in-history. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Barbosa, K., Spagnolo, G. (October 2019). "Corrupting Cartels: An Overview of the Petrobras Case" (PDF). Econstor. Retrieved from https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/249246/1/hasite0051-1.pdf. line feed character in

|title=at position 39 (help); Check date values in:|access-date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Zaveri, Mihir (November 9, 2015). "Pasadena refinery at center of Brazilian corruption probe". Chron. Retrieved from https://www.chron.com/neighborhood/bayarea/news/article/Familiar-Pasadena-refinery-a-focus-of-major-6619436.php. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Petrobras to sell Pasadena, Texas, refinery". Reuters. (n.d). Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-petrobras-divestiture-idUSKBN1FQ36B. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Sotero, Paulo (n.d). "Petrobras scandal". Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/event/Petrobras-scandal. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ "Paulo Roberto Costa, former director of Petrobras, dies at the age of 68". Newsbeezer. August 14, 2022. Retrieved from https://newsbeezer.com/brazileng/paulo-roberto-costa-former-director-of-petrobras-dies-at-the-age-of-68/). Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Nicoceli, Artur (August 14, 2022). "Morre ex-diretor da Petrobras Paulo Roberto Costa, aos 68 anos". Retrieved from https://www.cnnbrasil.com.br/nacional/morre-ex-diretor-da-petrobras-paulo-roberto-costa-aos-68-anos/. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Brazil ruling party's treasurer charged in Petrobras scandal". The Guardian. March 16th, 2015. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/16/brazil-ruling-party-workers-petrobras-rousseff. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ "Former Petrobras exec details corruption scheme in hearing". Reuters. March 10th, 2015. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-petrobras-hearing-idUSKBN0M620R20150310. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ "Ex-Petrobras CEO Bendine convicted of corruption in Brazil". Reuters. March 7th, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-corruption-bendine-idUSKCN1GJ37B. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ "Former Petrobras executive sentenced to five years jail". Reuters. May 26th, 2015. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/petrobras-corruption-idUSL1N0YH1R620150526. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ "Brazil Petrobras former director Jorge Zelada jailed". BBC. February 1, 2016. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-35467529. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Spagnuolo, Sergio (August 3, 2015). "Brazil police arrest Lula minister in bribery scandal". Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-petrobras-dirceu-arrest-idUSKCN0Q81HH20150803. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Ex-treasurer of ruling party gets lengthy jail term in Petrobras corruption scandal". The Guardian. September 21, 2015. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/21/ex-treasurer-workers-party-sentenced-prison-petrobras-corruption-scandal. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Brazil ruling party's treasurer charged in Petrobras scandal". The Guardian. March 16, 2015. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/16/brazil-ruling-party-workers-petrobras-rousseff. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Brooks, Brad (November 3, 2016). "Ex-Brazilian finance minister to stand trial in Petrobras graft case". Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-corruption-palocci-idUSKBN12Y2PF. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Spagnuolo, Sergio (September 14, 2016). "Brazil's Lula charged as 'top boss' of Petrobras graft scheme". Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-corruption-idUSKCN11K2C6. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Ellis, S., Athayde, A. T. (October 26, 2018). "The biggest corruption scandal in Latin America's history". Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uMXumMJZYYI&t=433s. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Barclay, Michelle (August, 2019). "CRISIS MANAGEMENT IN THE MIDST OF OPERATION CAR WASH". Retrieved from https://cms.law/en/hkg/publication/crisis-management-in-the-midst-of-operation-car-wash. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ Gallas, Daniel (April 17, 2019). "Brazil's Odebrecht corruption scandal explained". BBC. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/business-39194395. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Reuters (June 17, 2019). "Brazil's Odebrecht files for bankruptcy protection after years of graft probes". Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-odebrecht-bankruptcy-idUSKCN1TI2QM. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Brazil's Odebrecht changes name to Novonor". Deutsche Welle. December 18, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.dw.com/en/brazils-scandal-hit-odebrecht-changes-name-to-novonor/a-55994035. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Swiss private bank sanctioned in Petrobras corruption case". (February 2, 2018). Retrieved from https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/business/pkb-lugano_swiss-private-bank-sanctioned-in-petrobras-corruption-case/43871552. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ "Petrobras corruption firms pay CHF200 million penalty". SWI. December 21, 2016. Retrieved from https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/business/global-prosecution_petrobras-corruption-firms-hit-with-chf200-million-swiss-penalty/42782934. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Farinelli, Gustavo (Sep 24, 2010). "BM&FBOVESPA Celebrates with Petrobras the Largest Share Offering in History". PR Newswire. Retrieved from https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/bmfbovespa-celebrates-with-petrobras-the-largest-share-offering-in-history-103732504.html. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 35.0 35.1 The Securities and Exchange Commission (September 27, 2018). "PETRÓLEO BRASILEIRO S.A. – PETROBRAS," (PDF). Retrieved from https://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2018/33-10561.pdf. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ NASDAQ (n.d.). "PBR Dividend History". Retrieved from https://www.nasdaq.com/market-activity/stocks/pbr/dividend-history. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Arruda de Almeida, M; Zagaris, B (2015). "Political Capture in the Petrobras Corruption Scandal: The Sad Tale of an Oil Giant". Lights Out For Oil? The Climate After Paris. 39: 87–99 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Reuters (February 20, 2015). "Six contractors sued in Brazil over scandal". Upstream. Retrieved from https://www.upstreamonline.com/online/six-contractors-sued-in-brazil-over-scandal/1-1-1169578. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Blount, Jeb (April 20, 2015). "As Petrobras scandal spreads, economic toll mounts for Brazil". Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-petrobras-impact-idUSKBN0NB1QD20150420. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Building and Wood Workers' International (n.d.). "Brazil's GDP shrinks, millions of jobs lost due to lawfare".

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Data Commons (n.d.). "Amount of Economic Activity(Nominal): Gross Domestic Production (As Fraction ofPer Capita) (Brazil)".

- ↑ Worldbank (n.d.). "Unemployment rate - Brazil".

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Blount, Jeb (April 20, 2015). "As Petrobras scandal spreads, economic toll mounts for Brazil". Reuters.

- ↑ Gillespie, Patrick (March 21, 2016). "Brazil's oil giant loses billions amid corruption scandal". Retrieved from https://money.cnn.com/2016/03/21/investing/petrobras-brazil-oil-scandal/. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "How much of Brazil's economy got lost in Petrobras scandal". (April 4, 2015). Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrapoza/2015/04/04/how-much-of-brazils-economy-got-lost-in-petrobras-scandal/?sh=488006c4228a. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ "Foreign direct investment, net inflows (BoP, current US$) - Brazil". Worldbank. (n.d). Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.KLT.DINV.CD.WD?end=2021&locations=BR&start=2003&view=chart. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ Cheatham, Ameila (April 19, 2021). "Lava Jato: See How Far Brazil's Corruption Probe Reached". Council on Foreign Relations.

- ↑ Atuan, George (Mar 6, 2023). "The New Old Government is Bad News for Petrobras". Seeking Alpha. Retrieved from https://seekingalpha.com/article/4584778-the-new-old-government-is-bad-news-for-petrobras. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Brazil Government Debt: % of GDP". CEIC Data. n.d. Retrieved from https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/brazil/government-debt--of-nominal-gdp#:~:text=The%20Central%20Bank%20of%20Brazil,Nominal%20GDP%20in%20local%20currency.&text=In%20the%20latest%20reports%2C%20Brazil,USD%20bn%20in%20Dec%202022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Petróleo Brasileiro S.A. – Petrobras Agrees to Pay More Than $850 Million for FCPA Violations". US Department of Justice. September 27, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/petr-leo-brasileiro-sa-petrobras-agrees-pay-more-850-million-fcpa-violations. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Petrobras Reaches Settlement With SEC for Misleading Investors". SEC. September 27, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2018-215. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 52.0 52.1 "Pomerantz achieves $3 billion settlement for investors in historic Petrobras class action suit". Pomerantz LLP. n.d. Retrieved from https://pomlaw.com/petrobras. line feed character in

|title=at position 42 (help); Check date values in:|access-date=(help) - ↑ Pierson, Brendan (January 3, 2018). "Petrobras to pay $2.95 billion to settle U.S. corruption lawsuit". Reuters.

- ↑ Millard, Peter (October 19, 2021). "Article: Petrobras Shareholders Burned by 'Carwash' Turn to Dutch Court". ISAF Management. Retrieved from https://isafmanagement.com/article-petrobras-shareholders-burned-by-carwash-turn-to-dutch-court/. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ LaCroix, Kevin (June 6, 2021). "Dutch Court Rules Petrobras Collective Investor Action May Proceed". The D&O Diary. Retrieved from https://www.dandodiary.com/2021/06/articles/international-d-o/dutch-court-rules-petrobras-collective-investor-action-may-proceed/. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 56.0 56.1 Long, Cara (June 17, 2019). "Brazil's Car Wash Investigation Faces New Pressures". The Foreign Policy. Retrieved from https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/06/17/brazils-car-wash-investigation-faces-new-pressures/. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Gallas, Daniel (April 17, 2019). "Brazil's Odebrecht corruption scandal explained". BBC. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/business-39194395. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Langlois, Jill (June 13, 2017). "Former Rio de Janeiro governor sentenced to 14 years in prison for corruption and money laundering". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from https://www.latimes.com/world/brazil/la-fg-brazil-governor-20170613-story.html. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ BBC (March 30, 2017). "Brazil ex-speaker Eduardo Cunha jailed for 15 years". Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-39442005. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ DW (May 19, 2016). "Brazil ex-presidential aide sentenced to 23 years". Retrieved from https://www.dw.com/en/brazil-judge-sentences-ex-presidential-aide-to-23-years-in-petrobras-probe/a-19266959. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Reuters Staff (April 22, 2015). "Former Petrobras executive Costa convicted in corruption case". Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/brazil-petrobras-conviction-idUSL1N0XJ1TB20150422. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Reuters Staff (April 22, 2015). "Former Petrobras executive Costa convicted in corruption case". Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/brazil-petrobras-conviction-idUSL1N0XJ1TB20150422. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Fonseca, Pedro (June 26, 2017). "Former Brazil finance minister sentenced to 12 years". Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-corruption-palocci-idUSKBN19H1LP. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ United Nations (April 28, 2022). "Brazil: Criminal proceedings against former President Lula da Silva violated due process guarantees, UN Human Rights Committee finds". Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/04/brazil-criminal-proceedings-against-former-president-lula-da-silva-violated. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Buschschluter, Vanessa (October 31, 2022). "Brazil election: Lula makes stunning comeback". BBC. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-63451470. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Neto, José Alexandre Buaiz (January 3, 2023). "Fighting corruption in Brazil: Federal Decree No 11,129 of 11 July 2022, regulating anti-corruption law". International Bar Association. Retrieved from https://www.ibanet.org/fighting-corruption-in-Brazil-regulating-anti-corruption-law#:~:text=On%2012%20July%202022%2C%20more,published%20by%20the%20Brazilian%20government.. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Benjamin, Teo (December 9, 2016). "Here's what happened when Brazil banned corporate donations in elections". World Economic Forum. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/12/here-s-what-happened-when-brazil-banned-corporate-donations-in-elections/. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)