Course:LFS350/Projects/2014W1/T7/Report

Executive Summary

Frog Hollow Neighbourhood House is a non-profit organization and volunteer-driven to provide support and enhance the lives of their community. We partnered with them to enhance the local food awareness in their community. Our project consisted of teaching grade 8 to 12 students about the benefits of local food through the application of tea making with locally grown herbs. Our understanding of local food is stated as foods grown within 50 kilometers or within the province providing that it is more economically, socially and environmentally beneficial such as minimizing costs, bringing the community together and reducing carbon footprint. To start, our research question is "How do youths (grade 8 to 12) perceive the benefits of producing food within the Frog Hollow community?" In order to investigate this question, we focused on creating surveys that can cover the different aspects that affect the youths’ perception in store bought food, eating locally grown food and the likelihood of eating more locally. As well as, allowing them to rank the items according to their perception, such as affordability, nutrition content and variability. Based on 29 students’ responses, the data show that the students valued affordability and high nutrition content, which are the beneficial factors of local food, but surprisingly they are least concerned whether the food eaten was local or not. This shows the disconnection between students’ knowledge in the term “local food” and its benefits. Regardless, the student still expressed they will potentially grow and eat more local food and help Frog Hollow build a community herb garden. The limitations of this research are being unable to validate the result gathered and follow up with an implementation to build a herb garden, unable to conduct more surveys and measure it there will be any changes overtime due to our limit in time; and our sample of students were chosen through snowball sampling, which the results will present biases and cannot ensure that it could be generalized to the entire youth population in Frog Hollow. We recommend developing after school programs and a food asset map to further encourage eating locally; expanding gardens to grow more fruits and vegetables, allocating more time in designing and conducting workshops and surveys; working with more than one group to cover all aspects; and having more communication between ourselves and Frog Hollow would be beneficial.

Introduction

Our research project was a collaborative endeavor between our LFS 350 group and our community partner, Frog Hollow Neighbourhood House (FHNH). Established in 1968 by a group of concerned citizens, FHNH aimed to support local families in alleviating the challenges of day-to-day life in East Vancouver [1]. Since then, FHNH has been a non-profit organization, which has been a volunteer-driven community service in the Renfrew community (East Vancouver) for the past 45 years. [1] They provide a wide range of services to their community: ranging from childcare and family programs to computer lessons for seniors and environmental sustainability programs for youths. Recently FHNH created a local food initiative; they constructed a vegetable garden.[1] Building on this project, they are planning to transform a small unused plot of land outside the community house into a spiral herb garden. These types of local food initiatives are essential educational and outreach tools to help communities conceptualize and frame their view of the local and global food system, as it targets the relocalization of the food system, which in turn will affect food sovereignty. Food sovereignty promotes the “social process methodology”, in which initiatives are taken on a community-to-community basis prioritizing local knowledge as well as local needs, cultures and conditions.[2]

Our research team was comprised of eight LFS 350 students. The goal of our project was to help FHNH build a herb garden. However, due to time and weather constraints, this was not feasible plan. As a segue to the actual construction of the herb garden, we hosted a Tea Making workshop for local youths (grade 8 to 12), in order to promote local food awareness and recruit youths in the construction of the herb garden. We framed our workshop and survey questions around our research question; “How do youths (grade 8 to 12) perceive the benefits of producing food within the Frog Hollow community?”

Systems Model of Frog Hollow Neighbourhood House

Research Method

The research part of this project was to investigate the perception of youth’s grade 8-12 about locally grown food in the Frog Hollow community. Our group designed a Tea Making workshop based on Frog Hollow Neighbourhood House’s interest in building a spiral herb garden for the community and allowing mainly youths, along with other community personals, to build, plant, harvest and use/sell their locally grown herbs right in their community. Within that workshop, our group handed out surveys at the end for the youths to fill out. The idea behind those surveys was to compare the different possible influencing factors when buying local food and which is shown to be overall the most influential. The community based learning part of this research was to help us understand the community’s, especially the youth’s current state of knowledge on locally grown food and how engaged they were during and after the workshop was held. Though we will not be working with Frog Hollow after this semester is over, we are hoping that this workshop will lead these youths to helping Molina build the herb spiral.

As mentioned earlier, we conducted two tea making workshop as the premise for conducting our research and were collecting data about the youths through our post workshop surveys. Initially, our group had hoped to have been able to have designed our surveys with open ended questions to fully capture the youth’s perception, but we later changed to questions using the Likert response scale. This gave the youths the chance to be able to rank their preferences between numbers 1 through 5, and they still had a range of choices to accurately depict their perspectives. During the first workshop, the number of participants we had was less than we expected, we had to change the arrangement of the workshop’s procedure. This lead us to conducting a second workshop, with only two group members leading and because we had such confusion with these two workshops, qualitative data collection was discarded from the initial mixed methods, so we only ended up with quantitative data.We were able to manage and collect our data by making sure the surveys that were given to youths had number codes on them to keep them anonymous. We also used snowball sampling because our workshop participants were selected through our community partner’s, Molina, partnership with the schools and word of mouth; hence will result in avoidable biases.

The herbs that were used in the workshop were based on the more commonly used and popular herbs.[3] Molina also was able to kindly donate rosemary, thyme, lavender, sage and pineapple mint to use as well. The link between fresh herbs and health benefits was a hard one to find, but people who have fresh produce within a close distance to their homes are more likely to have a “healthier” lifestyle.[4] We did explain to the youths that herbs grown locally do have more flavour, nutrients, economically better and you actually know where your food is coming from (Klavinski, 2013).[5] At first it was really hard to be in contact with our community partner because we were originally partnered with two university students, who had busy schedules and unable to make final decisions. Later on, we were able to come in contact with Molina, the community partner in charge of the two students. She was very helpful to us in helping us set up some workshops with the schools she usually works with, providing us with herbs and kettles at our workshops, letting Frog Hollow’s youths know about our two workshops and even checking in on us to see how things were going.

As a group our ethical responsibilities included, making sure we were not doing anything to harm the youths or Frog Hollow or our group during the workshops, as well as protecting their privacy. Our group also needed to make sure we were presenting these workshops in a professional manner with the proper etiquette and choice of words. We did need to get consent from Frog Hollow and these youths to conduct these workshops. The student participants were underage and were considered as minors; therefore, they were unable to sign the consent form. As our TA and Eduardo’s suggested, we sent a copy of our consent form to the community partner in hope that she would forward the consent form to the student parents. After weeks and effort to follow up the community partner, we assumed the consent forms had not been sent out, we decided that we would be using pictures that are only showing students back or our properties. We also did not record the student names in effort to keep their anonymity and would not publish any information that could potentially affect their information privacy. We also would like to mention that the students were voluntarily and willingly to participate in the workshop and survey.

Results

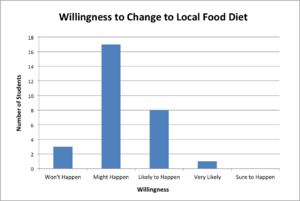

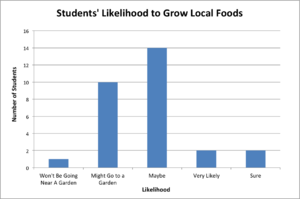

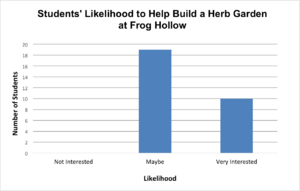

Based on the survey gathered from 29 students, Figure 3 shows that students are aware and know some basic knowledge on local food, they know that local food is nutritious, can be easily accessed, and also it is growing own food. In Figure 1, students picked affordability and nutrition are the most important and localness is the least. From here we found out that students are least concerned about the localness of the food. On the other hand, by combining figure 1 and figure 2, students might and potentially change their diet to more locally grown food, if the locally grown food products are more nutritious and affordable compare to the commercially grown food products. However, based on figure 4, overall students have little interest on managing their own garden, but figure 4 shows positive trend on helping the frog hollow to build and to manage their herb garden.

Discussion and Conclusion

Discussion

Our results show that the youths perceive the benefits of local foods to be high in nutrition content and it is affordable. They understand that there are benefits involved with local foods such as it lowers carbon footprint, easy to access, and it provides employment for farmers. However, local foods are not scientifically proven to be higher in nutrition content compared to other foods. Dunning[6] explains at the moment there are no scientific research to conclude that foods from local food systems are higher in nutritional content compared to the conventional system. This shows that there is a misunderstanding with the youths about the benefits of local food systems as they perceive local foods as being high in nutritional content. Our results also show that many youths are interested in helping Frog Hollow Neighbourhood House build their herb garden as many wants to have easy access to affordable food.

The focus of our research was to explore how the youths' perceived the benefits in initiating food growing projects within the Frog Hollow community. Our results determined the youths' criteria in food selection, willingness to altering diets, perceived importance in local-conscious choices, likelihood in organizing personal food-growing projects, as well as the potential in participating in Frog Hollow Neighbourhood House's herb garden project. The aspects we've measured, when combined, generates a general profile which then provide rather comprehensive insights into the youths' attitudes and beliefs toward locally grown foods and food products.

For the youths within the Frog Hollow community, affordability and nutritional content, although wrongfully so, have been highlighted as a key factor in local food selection, and that they display modest to high levels of interest in personal and communal food projects. These findings could be proven useful in commercial and organizational settings, as well as be applied toward academic development. Businesses and community food organizations, through identified types of attractions local foods provide youths, as well as their respective magnitudes, could formulate marketing strategies for existing projects and products to further peak their interest, and in turn increase their responsiveness. Also, future projects can be oriented, based on our results, to be more appealing to the youths. In terms of academics, the results demonstrated that although Frog Hollow youths have been exposed to the ideologies surrounding local foods, their scope is limited and, in certain aspects, incorrect. Current curriculums should aim to correct any misunderstandings and false beliefs, and seek to expand the youths' awareness toward food related subjects and benefits; mapping of their change in perception is also advised in order to fine tune any academic developments.

Although helpful, the results are not without limitations. The most prominent is the duration of our research in comparison to Frog Hollow Neighbourhood House's food project. We've collected responses from youths regarding their likelihood in aiding the execution of the herb garden project; while truthfulness of these responses are presumed, we have no opportunities in validating the actual number of youths joining due to our short involvement with Frog Hollow Neighbourhood House. Another limitation to our project is time. A lot of changes in our research method were changed due to time constraints. Our change in our survey style was one of them. Ideally we would have had a pre and post survey, so we could see how much the youths knew about local foods before the workshop and to see how much their knowledge and perspectives had changed after the workshop was completed. If given more time on this project, more surveys conducted on the same students over a period of time would have been the ideal way to see how the student’s perception of local foods change over time.

As aforementioned, affordability is the most influential factor in the youths' decision whether locally grown and produced food products should be chosen over other commercially available foods. This phenomenon echoes Dr. Gulati's in-class presentation, where he outlined that lowering pricing across the border is the single most effective method in promoting and popularizing local foods.[7] This suggests that community organizations and sustainability conscious businesses should prioritize efficiency in production and other areas, while protecting and retaining localism principles.

Conclusion

There are several recommendations we would suggest to Frog Hollow Neighbourhood House. First, we recommend that they have an after school program for their herb garden project. We believe that this is a big project and it will require committed students in order for this project to work out. Our results state that many students are interested in being involved with the garden. Our second recommendation is that they expand their project from a herb garden to fruit and vegetable garden where they could assess the food asset around the community member to raise awareness of local foods. From our results, we believe that having a food asset map would increase the awareness of local foods and their sources as many students have many misunderstandings of the benefits of local foods. By building a food asset map they would be able to learn more about the benefits of local foods. Thirdly, we recommend them to work with more than one LFS 350 group to focus on different components of the project such as marketing/management, agriculture research, and public’s opinion. Our final recommendation to Frog Hollow is to allocate more time for the workshops to give the presenters and the students more time to interact and present.

In conclusion, our workshop helped us discovered the youths do not fully understand the different aspects of local foods (location and relating benefits), but still perceived to value high nutrient content and affordability in buying food, and slightly interested in growing their own food. These results show that the youths will require more education or hands on experience to fully grasp the benefits of local foods. Our workshop might not make significant impact on food security, but we hope to raise awareness of about local food systems. Continuous efforts and supports are needed to reinforce to build a healthy community food system in our neighbourhood.

Appendix

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Frog Hollow Neighbourhood House. (2011), Mission & Value Statement. Retrieved October 22nd 2014, From http://www.froghollow.bc.ca/mission-value-statement

- ↑ Wittman, H. (2011). Food Sovereignty: A New Rights Framework for Food and Nature?. Environment and Society: Advances in Research, 2(1), 87–105.

- ↑ Health.com. (2014). 10 Healthy Herbs to Grow (and Eat) at Home. Retrieved on November 4th 2014. From http://www.health.com/health/gallery/0,,20705274,00.html.

- ↑ Kiefer, EC., Sinco, B., Kim, C., (2006). Health Behaviors Among Women of Reproductibe Age With and Without a History of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. Volume 29, Number 8, 1788-1793

- ↑ Klavinski, R. (2013), Benefits of Eating Local Foods. Retrieved October 29th 2014, From http://msue.anr.msu.edu/news/7_benefits_of_eating_local_foods

- ↑ Dunning, R. (2013). Research- Based Support and Extension Outreach for Local Food systems. retrieved November 29 2014, from http://www.cefs.ncsu.edu/resources/guides/research-based-support-for-local-food-systems.pdf

- ↑ Gulati, S. (2014). Food and Resource Economics [PowerPoint Slides]. Retrieved from https://connect.ubc.ca/webapps/blackboard/execute/content/file?cmd=view&content_id=_2473659_1&course_id=_47329_1