Course:LFS350/Projects/2014W1/T22/Report

Executive Summary

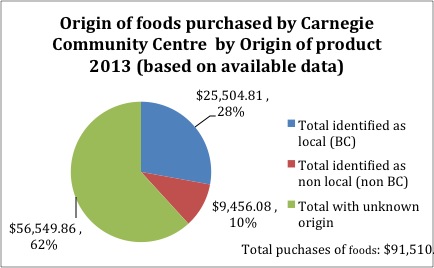

Our group worked with Carnegie Community Centre (CCC), which runs a non-profit kitchen that provides low cost meals catering to low-income residents in the area. In alignment with the City of Vancouver’s (COV) goal to increase local and sustainable food, we proposed our research question: “How sustainable is the current Carnegie Community Centre Food Procurement Program?” Our original research plan was to conduct quantitative research on CCC’s food procurement practices and to provide them with a baseline assessment to showcase the percentage of local food purchased. We used velocity reports provided to CCC by their vendors as well as invoices and receipts kept at CCC. If time allowed, we would then look for possible methods to increase local food purchases. Due to insufficient and incomplete data provided by CCC’s suppliers, we were unable to come up with an accurate percentage of the amount of local food bought by CCC. From analysing the partial data given, we found that 28% of CCC food purchases were local, while 10% were non-local, and 62% had an unknown origin. We found that what the COV expected of CCC in regards to tracking local spending was unrealistic given the current tracking done by suppliers. We provided CCC with a needs assessment of what information they would need in order to be able to track their percentage of local purchases. Ultimately, we recommend that in order to track food purchases, suppliers would need to change their system and better track where their foods are coming from. As well, the COV should reconsider their expectations for tracking local spending. Our key limitations were a lack of time and incomplete data.

Introduction

In 2014, the City of Vancouver (COV) decided that the production and consumption of local and sustainable food was a priority for the COV as reflected in both the Greenest City Action Plan and the Vancouver Food Strategy. As a food purchaser, the City can play a role in encouraging local and sustainable food through its own procurement practices. The City purchases about $5 million of food from 400 unique vendors every year (Craig, 2014). Where and how this money is spent can have major impacts on jobs, the environment, viability of enterprises, and even the health and well-being of entire communities.

A study cited by a recent COV report states that “buying from a BC office supply company resulted in 77 to 100 % more local economic activity, and provided twice as many jobs within the province, when compared to buying from a multinational office supply company” (Duffy, 2013). As well, sourcing local producers can increase levels of food security while reducing the amount of greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions due to decreased transportation distances, reduced levels of petroleum based fertilizers, and minimized amounts of packaging and processing.

As a result, the City launched a campaign to increase the percentage of food procured to be “local” and “sustainable”. Local food was defined as: “(a) raised or grown or produced or processed within a 325 km radius of Vancouver; or (b) grown and transported in a way which has no more of an environmental impact than (a).” Sustainable food was defined in the COV Local and Sustainable Food Procurement project outline as essentially foods certified by various trusted food agencies as sustainable (Craig, 2014):

As part of the Local and Sustainable Food Procurement project, making local, sustainable food available in City and Parks facilities is in alignment with three key City documents: the Greenest City Action Plan, the Vancouver Food Strategy, and the Park Board Local Food Action Plan, (Craig, 2014) whose goals include:

- Making local food more available in community centres,

- Using the city’s purchasing power to buy sustainable, locally produced food, and

- Increasing locally- sourced, higher-nutrition, and sustainably-packaged food sold and processed in Park Board system through collaboration, procurement rules, permits and licensing, and other tools.

The Carnegie Community Centre (CCC) operates out of one of the City’s oldest buildings on the corner of Main and Hastings. The centre is open 7 days a week from 9am to 11pm, and is available to members for a $1 annual membership fee. Most services, including the cafeteria, are offered free of charge or at a substantially reduced cost. The Carnegie kitchen is one of three COV- run kitchens. The non-profit kitchen prepares and serves three healthy meals daily from scratch. Of the three kitchens, Carnegie produces the largest volume of food. The number of lunch servings averages around 240 portions, and about 160 portions for dinner. The centre also hosts many local events, such as town hall meetings, luncheons with chief of police, and art and culture events, all of which are also catered by Carnegie’s kitchen.

Eager to align with the COV’s Local and Sustainable Food Procurement project, CCC enlisted the help of UBC students from the faculty of Land and Food Systems to carry out an assessment of the sustainability of the current food procurement practices at the centre. While they have the information available, the centre lacks the time and personnel to do an analysis of the sustainability status of the current food purchases of Carnegie Community Centre. Thus, with support of our community partners at the centre, our group planned to produce a baseline assessment of the current food procurement practices at CCC. All of our data would be based on the most current, completed year, January to December 2013, and would be used to address the following research question:

How sustainable is the current Carnegie Community Centre Food Procurement Program?

To determine the above, we will look at the following:

- Determine the total percentage of local foods, as defined by the COV criteria, purchased in the predefined time frame

- Identify the top 8 foods purchased based on proportion of budget

- Determine what percentage of each of these top 8 food items are purchased locally

- Determine strategies to increase % of local sustainable foods or alternatives

By providing a baseline assessment of the current food procurement practices, we will identify the gaps that must be addressed in order to allow the centre to align with the City’s goals as outlined above.

Systems Diagram of Carnegie Community Centre

Research Methods

Original Plan

While a mixed methods approach, including quantitative and qualitative data collection often provides a fuller ‘answer’ to a research question, the concerns and interests of our community partner were better served by a strictly quantitative data focus, which is what we intended to use (Creswell, 2013). Typically, change is more easily accepted when supported by numerical evidence, especially with respect to buying and purchasing habits. Thus most of our data collection focused on velocity reports (also known as purchase reports) from all the different vendors Carnegie purchased from over a one-year time frame. Obtaining the necessary information for our planned data analysis required cooperation with Steve McKinley, the kitchen coordinator, who was diligent as our liaison between his vendors and us. Communication with Steve occurred through primarily email, as well as once monthly meetings with both Sharon (assistant director of Carnegie) and Steve.

After compiling a spreadsheet with this information we intended to determine:

1) Total spending of Carnegie kitchen in a year

- As the COV has encouraged the increase of local food purchases by its community institutions, we planned to calculate the percentage of yearly food purchases that were obtained from local producers.

2) Foods consuming the greatest percentage of the kitchen budget and their locality

- After identifying the top 8 foods that consumed the greatest percentage of the food budget, we wanted to determine what percentage of each food item is purchased from local vendors. Contacting vendors to determine where foods are produced, processed and/or distributed locally, and if so, to what degree, was also considered. Foods with unknown origin due to lack of information or due to lack of time to obtain information were classified as “unknown locality” and thereby were excluded from our percentage calculation.

3) The feasibility of increasing the total the percentage of local purchases

- Increasing local purchases could include increasing volume of purchases from specific vendors, changing vendors, or splitting purchases between vendors. This would involve researching different local vendors in the area, using Carnegie Community Centre as a centre point, and contacting these vendors to determine the cost of the product of interest, as well as the capacity the vendor has to provide for Carnegie. If there are no local or organic options available for a specific product, we may suggest a food item that is nutritionally similar and can also be acquired from local sources. However, given the socio-economic nature of the neighbourhood and the tight budget of the kitchen, cost may be the greatest barrier to purchasing more local, sustainable and/or organic foods. Thus, ethically we must consider the costs variance of using a different vendor with more local products before making recommendations.

We were given velocity reports in mid-October via email. Both Sharon and Steve emphasized that communication with distributors can be very difficult and thus graciously acted as our main information liaisons with the vendors. Additional research and data collection was to be conducted on-site due to confidentiality issues of the documents (receipts and invoices). On-site data collection was to begin on October 22 and continue over the week, providing 1 week for analysis and 2 weeks to compile a report. Due to time constraints, we agreed with the community partner that our goal would be met if we completed 1 & 2 above, with 3 as a bonus if time allowed.

However, on our first day of on-site data collection, we discovered that the data was incomplete and insufficient to determine how local CCC food purchases were (details will be discussed in the Results and Findings section). Another meeting was held with Sharon and Steve to discuss if further details could be collected about the locality of the food from their vendors. Despite a second attempt to obtain the data and our community partner’s efforts to provide us with the documents that we had hoped for, we were still unable to acquire complete data.

Findings

Results

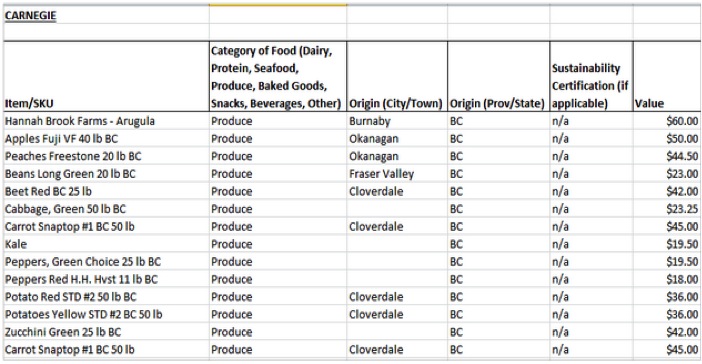

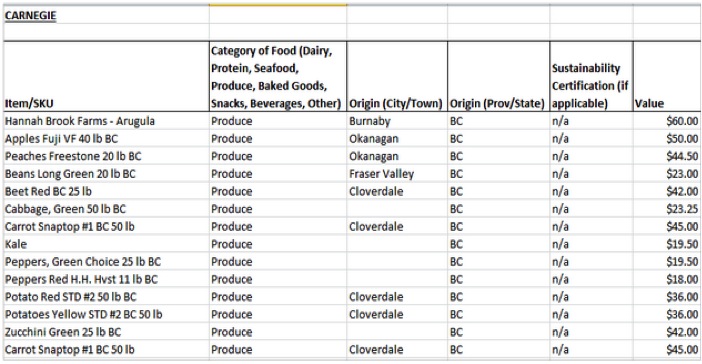

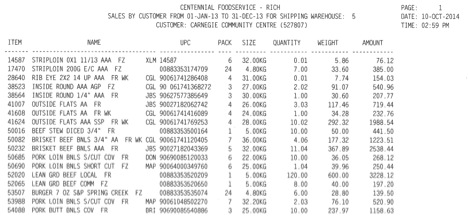

Our expectation of the data’s format was likely idealistic when considering the free market place. We hoped and expected for data as shown in Figure 1 which includes: Product Name, Origin (based on city and province), and Price per Unit. However, we learned this chart was only an example of an ideal data compilation, provided by the COV to Carnegie Community Centre. The reports and information we received were not as streamlined.

Velocity Reports

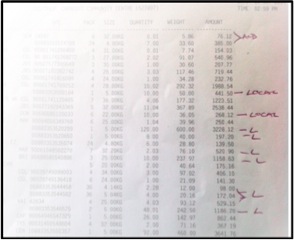

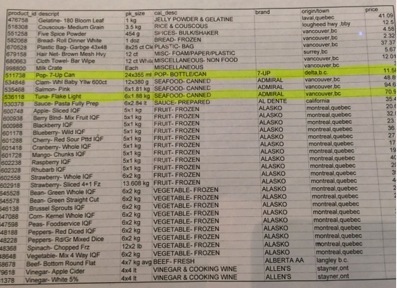

Velocity reports were detailed with respect to food items, purchase price, and quantity purchased. However, in many reports, locations and origins of the foods purchased were unspecified, or only stated the country or continent of the food’s origin. Others only recorded the location of distributors, but not where the food was actually grown or produced. Each velocity report also differed substantially in format and coding methods, impeding our ability to decipher additional information from the reports. We also identified that the data which did contain product origins may have been unreliable. For example, it was indicated that 7-UP was produced in Delta (Figure 3).

Unfortunately, despite a second meeting with our community partners, our failure to communicate the specificity we needed with respect to locality hindered our attempts to additional information on product origin for these velocity reports. While the community partner was very supportive in providing us with the information about which foods were ‘local’, this information was denoted by a list, or the letter “L” and prevented us from precisely determining whether the foods fit the COV definition of local.

Invoices and Receipts

Unfortunately, these pieces of information were also ambiguous and lacked sufficient and consistent information. Many invoices and receipts did not specify food origin. Supplier name, type of food item purchased, and specific item purchased were often missing. Some invoices were blank or contained vague descriptions, preventing us from identifying the type of food purchased or where the food was originated.

For confidentiality reasons, the invoices and receipts did not include purchases made with a credit card. The credit cards were used to make large purchases, but these records were kept by the COV. To access the credit card transactions, we would need to undergo tedious applications and processes, and even then we are not guaranteed any substantial information without cross-referencing a purchase history report.

As a result, we halted all data collection to re-evaluate our goals.

Analysis on Partial Data

Based on what was available to us, we made an attempt at data analysis. From what was given, we found that 28% of the food purchased by Carnegie in 2013 could be identified as local, and 10% as non-local, with BC as our boundary. The remaining 62% was food purchased with unknown origin. With the current incomplete data, we were unable to accomplish our initial project plan. However, our findings show that there is a tremendous gap between the city’s expectations and what the current data tracking systems can provide. Through our different efforts at data collection, both in-person and through e-mail communication, we discovered that it was not only tedious work required, but the entire process was complicated and messy, as systems issues can be.

Discussions

While we believe that our research question is indeed answerable, we concluded that, given the time constraints, the flaws in the current record keeping system, and the slow manner in which community projects typically unfold, we are unable to answer our original research question at this time.

We have identified that with the variety of tracking systems of distributors in the lower mainland, our research question, which was derived from the COV’s Local and Sustainable Food Procurement strategy, may be too tedious and time consuming for centres such as Carnegie, which are operated by limited staff, to complete. Data from distributors lack information and/or detail, and is often hard to obtain. Based on what is currently provided by the different suppliers, we think that the City of Vancouver needs to re-evaluate their expectations and mandate more credibility from suppliers.

This is important for the food sovereignty of Carnegie Community Centre and the community of the Downtown Eastside. Wittman, (2011) says that food sovereignty is “the ongoing conversations about what kinds of trade relations will best serve the social, economic, political, and environmental principles of an alternative food paradigm.” Should a tracking system be developed in the future, the information that would be provided to Carnegie Community Centre will empower them with choices and allow them to make informed decisions on their suppliers, thus increasing food sovereignty. This is also important for the continued survival of local and regional food producers. By increasing the food sovereignty of Carnegie Community Centre and other facilities like it, local producers will have more business and thus more capital to invest in their farms for production. With more food produced, in a larger variety, food security in the region can also be increased with more affordable produce.

Recommendations

The current variability of distribution tracking systems makes COV expectations very difficult to achieve. In this section, some recommendations will be made. One suggestion for COV to achieve a standardized method for product tracking is to create a template form for suppliers to report. Suppliers would then be expected to produce a compliant tracking and record keeping system, which would be accessible and transparent with respect to the locality of their products.

From our experience of community-based learning, this may be met with some resistance from suppliers. Carnegie Community Centre could assist their suppliers to improve tracking of goods. Also, they could begin streamlining internal tracking to be compliant with City requirements. Additionally, Carnegie could identify their highest purchased food items and begin more stringent tracking methods. Furthermore, to ensure that their neighborhoods have equal access to local and sustainable food, Carnegie could begin identifying their own locally sourced food percentage (LSF%) increase strategies.

Conclusions

In the process of assessing the food-purchasing status of Carnegie Community Centre, a major problem was found when identifying the origin of food from the data collected by suppliers. A reliable and consistent food-tracking system is a crucial component for producing a reliable report that would answer our initial research question of identifying how sustainable and local Carnegie Centre food purchases are. Hence, it is suggested that changes might need to be made in the current food-tracking system in order to increase both accountability and credibility of suppliers, in order for accurate and complete analysis of the local food procurement practices at Carnegie Community Centre.

References

Craig, K. (2014). Local & Sustainable Procurement in City Facilities Sustainability Support Services Report. Vancouver: City of Vancouver.

City of Vancouver Internal Working Group. (2014). Local & Sustainable Food Procurement Project Summary and Recommendations. Vancouver: City of Vancouver.

City of Vancouver. (2014). Defining COV’s Approach to Local and Sustainable Food Procurement. Vancouver: City of Vancouver.

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications. (pp. 3-23)

Duffy, R. A. (2013). Buying Local: Tools for Forward-Thinking Institutions. Vancouver: Columbia Institute, LOCO BC, ISIS Research Centre at the Sauder School of Business.

Wittman, H. (2011). Food Sovereignty: A New Rights Framework for Food and Nature? Environment and Society: Advances in Research, 2(1), 87–105.

Appendices

Appendix 2: Recommendations Report for Carnegie Community Centre

In 2014, the City of Vancouver (the City) decided that the production and consumption of local and sustainable food was a priority for the City as reflected in both the Greenest City Action Plan and the Vancouver Food Strategy. As a food purchaser, the City can play a role in encouraging local and sustainable food through its own procurement practices. The City purchases about $5 million of food from 400 unique vendors every year. Where and how this money is spent can have major impacts on jobs, the environment, viability of enterprises and even the health and well-being of entire communities.

As a result, the City launched a campaign to increase the percentage of food procured to be “local” and “sustainable”. The City has a target of at least 40% of food purchases to be determined as local and sustainable by 2016. A strategy recommended by the City to increase LSF purchases is to identify the top 20 items purchased and devise a strategy to increase LSF purchases by focusing on increasing percentage of these products being LSF.

Carnegie Community Centre (CCC), as a City facility, is required to be compliant with the City’s mandate of increased purchases of Local and Sustainable Food (LSF). Therefore a strategic plan must be considered by CCC in order to achieve compliancy.

Present data tracking and reporting

The City expects data reported to be presented in a very specific model with an example shown below:

However, the reality is that actual tracking reports provided by vendors are often inconsistent, with various different tracking codes and data that is at times difficult to interpret and fit in with a larger tracking strategy. See Example below

The data often is presented in a form that is inconsistent with the City’s requirements, and in numerous cases, missing important data that is required for CCC to comply with the City’s requests for tracking unless there is considerable data manipulation by either the vendor or by CCC staff.

Present situation

At present based on available tracking data, CCC’s LSF situation is as such:

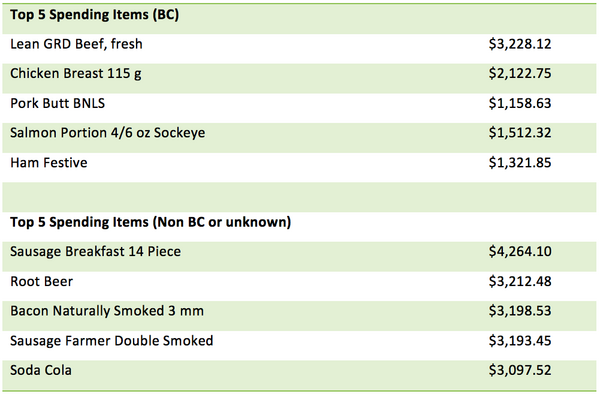

With the top 5 items of BC and non-BC origin as such:

Issues arising from usage of presented data

While the data presented shows a favourable snapshot of the present situation CCC is in with their compliance to the City’s mandated goal of LSF designated purchases, several key issues must be considered when using the presented data:

• Completeness of data

- o Data shown is only a proportion of total purchases, and the actual percentage of total spending this data represents is unknown

- o Some records were incomplete or informal (receipts in a box, no formal tracking)

- o A percentage of spending was unavailable (credit card receipts stored in a separate location)

- o Product sustainability report and background unavailable or non-existent

• Source data available from vendors determined to be potentially unreliable or incomplete

- o Vendors did not keep good records of the actual source of the produce

- o “Product pooling”. Items of different sources were placed in larger pools (eg Apples)

- o Difficult to decipher product codes and tracking

- o Inconsistent data tracking by different vendors (eg Lean GRD Beef vs Lean GRD Beef, local)

• Data labeling inconsistencies

- o Similar items may be labeled different items by different vendors

- o Products could be categorized by brand (eg Rogers Sugar vs Sugar) and not specific product, and be difficult to track and compile total spending of a food item

Strategies for moving forward

In light of these challenges in meeting the expectations of the City and the reality of the situation at hand, the following recommendations are presented:

1. Begin a more comprehensive internal tracking system for purchases.

- • Formalize all purchases within a internally agreed upon format in order to ensure compliance with City standards

- • E.g. Informal local purchases either in a cash or credit card format should be tracked in accordance to City requirements, by being put into an internal tracking spreadsheet , or other form of easily accessible database

2. Work with vendors to improve tracking of goods

- • Present City tracking requirements to vendors, specifically in the format that the City requires in order to begin preparing for the eventual compliance mandate.

- • Specify what exactly is required by the City by presenting them the example spreadsheet as a template for what is needed in terms of tracking of produce

3. Identify highest purchased food items, begin more stringent tracking methods and identify LSF percentage increase strategies

- • By identifying highest purchased food items, increasing their percentage of LSF would provide the biggest “bang for the buck” when improving overall LSF percentage compliance