Course:GEOG352/2019/Water Scarcity in Amman, Jordan

Introduction

Water is essential to life; yet its use is liberal and mainly unmonitored. Fresh water is a finite resource that is now defined by the United Nations as a human right. However, water shortages have led to the commodification of water with a high monetary value. The expanded adoption of this neoliberal practice has created a need for the development of informal markets alongside formal ones. Out of insecurity and desperation arising from ineffective state action, citizens are compelled to participate in urban politics to fulfill their needs. The formal water commodification market creates social inequalities which lead to the creation of grassroots initiatives. These formal markets are prevalent and successfully used in the context of the global north but are not applicable to contexts within the global south. The analysis of water scarcity must be done through a lens of critical urbanism, where the significance of place is central as opposed to a universal model which assumes that one solution can be applied globally [1]. The specific needs of each city and its population should be central to the design of water management systems and service provisions. Essentially, what works in the West might not work in geographical south and east.

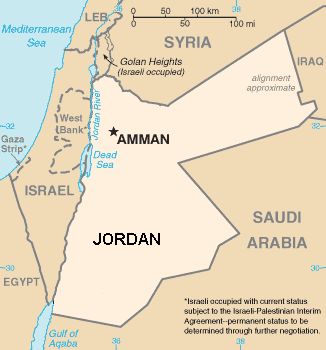

Urbanization is one of the largest threats to water scarcity [2]. Cities like Amman, Jordan, are not able to effectively implement programs and services that can adapt to a rapidly changing climate, population pressures and are aggravated by the lack of prioritization by government of infrastructural provisions. As a result, Amman is experiencing one of the most significant water shortages in the world[3].

Overview

Water scarcity affects over 40 percent of the world’s population and is going to be exacerbated in the face of environmental changes, population pressures and urbanization[4]. If the rising levels of scarcity are not properly mitigated, there are projections that up to 700 million people could be displaced by water supply shortages by the year 2030 [5]. Apart from the immediate effects of water scarcity, that of a lack of appropriate drinking water, many other crises, such as food insecurity and land morphology, stem from it. According to the United Nations, an “absolute scarcity” of water is when an individual’s average annual supply of water is less than 500 cubic meters[6].

Importance of Water Scarcity

The issue of water scarcity is important when viewed from the perspective of water as a human right. As a human right, the importance of water becomes prominent because it is fundamental to life. Clean water keeps people healthy and allows people to carry out their jobs and day-to-day activities. Water also allows for proper sanitation and good hygiene, thus reducing the possibility of diseases from arising. When water is seen as an entitlement, it becomes a source of dignity and prosperity for billions of people around the world. With a dependable source of proper drinking water, people will shift their focus away from securing access to water and may begin to engage in their local communities and maximize their own well-being.

Current water supply shortages are leading to a rise in the incidence of diseases, poor sanitation and dried-up crops, all of which have negative impacts on urban dwellers. Health hazards like heat stroke and heat exhaustion that arise in regions of high temperatures further put pressure on water and water-intensive energy sources such as through the high uses of air conditioning[7]. In addition, the depletion of groundwater sources results in the loss of soil moisture leading to accelerated processes of desertification[8]. Desertification also leads to the loss of arable land suitable for agricultural production, driving more people out of rural areas into the city, and putting additional pressure on the city’s infrastructure.

Water Scarcity in a Neoliberal City

Formalization and privatization of the water market creates a better quality supply, but also forms issues of in-access to the urban poor[9]. Water scarcity has created patterns and privileges of water consumption that sustain specific social orders along the lines of class. Access to water has become a way of organizing daily life. Due to the capitalist commodification of water sources, those with higher incomes and social status, or those who have relations with politicians or city officials, enjoy significantly better water supplies.

The issue of water scarcity is a representation of the absence of ecological urbanism; a polarization in the relationship between nature and humans. Even in dry, arid regions, people use water for unnecessary, superficial purposes and in doing so, do not practice proper water conservation due to the fear that the water will disappear.[10] The belief in the citizen body and the environmental condition is detrimental to their future, yet they consume water at tremendous rate. Environmental lifecycles should be more fully integrated into infrastructural building and planning processes in order to enable a more balanced relationship with humans and their surroundings [11].

Water Scarcity in Amman

Water scarcity is a global phenomena following the trends like de-colonization and mass migration. In Amman, the issue dates back to its colonial occupation. Since gaining its independence in 1946, the priorities of the Jordanian government has been that of nation-building, while neglecting plans for long-term sustainability[12]. Tensions created by the unexpected migration of refugees from neighbouring conflict-torn countries, coupled with a lack of sustainable development plans, have put tremendous pressures on the state to the point where it has ignored the misuse of water sources[13]. Refugee movements from political struggles in newly independent countries along with the trend of rural to urban migration have created uneven conglomerations of people within cities. City growth is often unprecedented and leads to the state being unable to provide services to all citizens equally without suffering from resource depletion, as with water shortages. Amman's colonial roots, alongside the city's geographical location and environmental characteristics, are compounded as a result of large influxes of refugees and an insufficient infrastructural system[14].

Case Study Amman

Environmental

Amman is located in the Jordanian Valley, a region that experiences high temperatures in the summer with variable rainfall throughout the year. Climate projections for 2050 estimate that regional temperatures will increase by 2.4 degree Celsius [15]. Amman’s hot, dry temperatures are further intensified by the dry Sirocco (Khamsin) and Shamal winds [16]. The dry winds and its landlocked location lead to high evaporation rates, aggravating Amman’s water crisis. Amman’s piped and well water comes from groundwater aquifers; dominantly the Amman-Wadi As Sir (B2/A7). Through satellite imagery, a downward linear trend has been observed of approximately 15 millimetres per year. The Amman Zarqa Basin’s yield needs to remain within a sustainable state is 87.5 million m3 per year, however the current pumping rate is 156.3 million m3 [17]. To add to bleak future water conditions, Amman’s fresh water sources are part of the Dead Sea Basin[18]. The slope gradient of Amman to the Dead Sea is significant enough that it is causing water tables to flow downwards and out of the aquifers. Once the water reaches the Dead Sea it becomes salt water, therefore undrinkable before a process of desalination.

Local efforts of urban sustainability have resulted in the manipulation of the land in the form of rain harvesting into small reservoirs [19]. The reservoirs hold rainwater in areas like Amman and its surrounding rural peripheries to mitigate unreliable rainfall and access to water. Urban ponds like these produce moderately high greenhouse gas emissions by flooding the soil and causing decomposition of organic material [20]. This process creates a positive feedback loop where the emissions contribute to temperature increase which in turn creates the need for more urban ponds.

Infrastructural

An estimated fifty percent of water destined for Amman's distribution system is unaccounted for due to leakage from its ageing infrastructure, inadequate billing and poor payment collection [21]. Ninety-eight percent of homes in Amman are connected to a piped water system, however on average they receive intermittent access to water for 36 hours a week [22]. Due to this intermittency, households are compelled to adopt alternative coping strategies for maintaining their water supply. Higher-income households commonly have rooftop water storage tanks as well as expensive basement cisterns installed to mitigate the lack of steady piped water supply, whereas lower-income households typically only have rooftop tanks. This creates varying storage capacities between high-income households (16.24 m3) and low-income households (3.12m3)[23].

The residents of Amman rely on formal and informal water tanker operators. Formal operators are given licenses through a public-private partnership with the state-owned Water Authority of Jordan (WAJ). Informal operators illegally extract groundwater and have emerged due to a need to service lower-income households[22]. Richer districts also tend to have more frequent access to piped water whereas poorer districts, such as Qasabet Amman and Wadi Essier, have the most infrequent supply of piped water. “Informal means of accessing water are not temporary phases,” and the use of a piped-water system directly into households, taken from the global north and implemented in the global south, is inadequate and inappropriately applied to Amman[12]. Neoliberal practices looking to fully formalize the water tanker market have attempted to halt informal practices but have largely failed because of a growing reliance on the informal by urban poor and marginalized populations.

In 2003, a construction agreement for the Wadi Ma’in, Zara and Mujib Water Treatment and Conveyance plant was signed, with 38 million cubic metres (MCM) going to Amman out of the total 53 MCM of treated water per year[24]. The treatment plant converts brackish, salinated water into potable water as a way to offset a lack of water supply. Unfortunately, desalination projects cannot be entirely relied upon as an alternative form of supply. Due to the fact that Jordan has no indigenous energy sources, the cost of supplying water increases as a result of importing the necessary energy. Amman is also located 1,000 meters above sea level, and pumping costs must be factored into the total expenditure, increasing total expenditure[25].

Social

Since the beginning of the Syrian Civil War, Amman has had a massive influx of refugees which has put a strain on the capacity of its urban public services. According to the government’s report, the population of Syrian refugees residing in Jordan increased from 10 percent of the pre-crisis population to 25 percent by 2008. The city’s water strategy that was implemented in 2008 was based on consistent population growth from about 5.8 million to roughly 7.8 million by 2022, but data showed that Jordan’s population had already reached 8 million by December 2013.

Amman’s existing water scarcity issue is creating tensions between the citizens of Amman and the refugees. NGOs have played a big role in addressing the needs of refugees, but they further distort the local market value of water.[26] NGOs and Ammanis are all vying for the use of municipal wells, creating animosity towards the refugees by Ammanis. NGOs are frequently willing to overpay for local water and have consequently priced some Jordanians out of the water market. Water use by refugees feeds into the perception that Ammanis are overlooked while the state's resources are directed to the refugees. In addition, water scarcity has produced a strained relationship between upper class Ammanis and lower class Ammanis. Those part of the upper class have relationships with politicians and have the money needed to access water whereas those part of the lower class do not have this privilege.[27] Thus, unequal social processes have become prevalent in Amman on the basis of water consumption.

Females in Amman generally have lower social status than males. The unemployment rate for women in Amman is relatively high which creates additional financial obstacles for female-headed households in Amman to reach private water sources. Deliveries of water from private water tanks also often prioritize male-headed households. According to local accounts, male truck drivers deliver water first to their friends, relatives and people with social prestige. Female-headed households or widows are often left out since they are physically limited by their ability to operate water tanks[28].

Lessons Learned

Overall, Amman’s physical and environmental characteristics place it in a difficult situation in which the city is constantly struggling to accommodate its growing population. While it has recently introduced water treatment plants and conveyor systems, its limited local fresh water availability and lack of native energy sources are not sustainable in the long-term. The competition between Syrian refugees and Ammanis for access to water also adds another dimension in the form of a contentious relationship. The presence of refugees creates the notion within Ammanis that their needs are being disregarded while the needs of the refugees are being addressed. Suitable long-term plans and strategies to address these issues will help alleviate some of these stresses and may provide valuable lessons for other contexts in the geographical south and east. Finally, while this case study examined the informality of water, research and data on informal settlements within Amman were not found. Information on these settlements would provide a broader image on water scarcity in Amman.

Cities in the geographical south and east with ‘informal’ water markets provide their services to households that would otherwise not be able to afford formal water. As a result of this case study, it has become evident that in order for geographical south and east contexts to have enough water, the binary that exists between the formal and informal must be erased. These alternative methods need to be recognized by the government as a crucial way for urban citizens to access water. Additionally, to mitigate the possible strain that may occur between refugees and citizens of the city with opposing interests, the voices of all parties need to be taken into account to find possible solutions that can work for everyone. Creating solutions that are based on one dominant voice will only create antagonistic urbanization processes.

The stereotype that women inherently occupy a low social status in Amman has created a situation where women have inequitable access to water sources compared to men. Asserting women’s rights in the context of equitable water access would help reform the situation where women are viewed as inferior to men, not just in this context but in other contexts as well. Urban-wide awareness campaigns and leadership training workshops may help women to retrieve their rights in the form of equal access.

In light of environmental issues in Amman, such as rising in-land temperatures resulting in higher evaporation levels, mitigation efforts need to begin at a local scale to help deal with water shortages. To offset falling freshwater levels, initiatives can be taken on to store rainwater and grey water for urban gardens, car-washing and various water-intensive activities. Research and development can be done on appropriate ways to create and manage urban ponds so that they do not aggravate green house gas emissions and lead to local temperature increases.

References

Reference List

- ↑ McPhee, S. (2019). Defining The Global South. Retrieved from University of British Columbia GEOG 352 Canvas site.

- ↑ United Nations. [United Nations. (n.d.). Water Scarcity. Retrieved 2019, from http://www.unwater.org/water-facts/scarcity/ "Water Scarcity"] Check

|url=value (help). United Nations Water. - ↑ Von Mayrhauser, M. (2012, July 09). Water Shortages in Jordan. State of the Planet. Retrieved from https://blogs.ei.columbia.edu/2012/06/20/water-shortages-in-jordan/

- ↑ United Nations. "Goal 6: Ensure access to water and sanitation for all". United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

- ↑ "Jordan urges better planning to address water scarcity". The Jordan Times. March 15, 2018.

- ↑ United Nations (November 24, 2014). "Water stress versus water scarcity". The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

- ↑ The World Bank Group. (n.d.). Climate by Sector Health. Retrieved from https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/jordan/climate-sector-health

- ↑ Al-Zyoud, S., Rühaak, W., Forootan, E., & Sass, I. (2015). Over Exploitation of Groundwater in the Centre of Amman Zarqa Basin—Jordan: Evaluation of Well Data and GRACE Satellite Observations. Resources,4(4), 819-830.

- ↑ McPhee, S. (2019, January 22). Economic Perspectives on the Urban in the Global South. Retrieved from University of British Columbia GEOG 352 Canvas site.

- ↑ Francis, A. (2015, September 21). Jordan's Refugee Crisis. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved from https://carnegieendowment.org/2015/09/21/jordan-s-refugee-crisis-pub-61338

- ↑ McPhee, S. (2019). Ecological Urbanism, Modernity and Sustainability. Retrieved from University of British Columbia GEOG 352 Canvas site.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Mustafa, D., & Talozi, S. (2018). Tankers, Wells, Pipes and Pumps: Agents and Mediators of Water Geographies in Amman, Jordan. Water Alternatives,11(3), 916-932.

- ↑ Mustafa, D., & Talozi, S. (2018). Tankers, Wells, Pipes and Pumps: Agents and Mediators of Water Geographies in Amman, Jordan. Water Alternatives,11(3), 916-932.

- ↑ MercyCorps. (n.d.). Tapped Out: Water scarcity and refugee pressures in Jordan. Retrieved from https://www.mercycorps.org/research/tapped-out-water-scarcity-and-refugee-pressures-jordan

- ↑ World Bank Group. (n.d.). Climate Data Projections. Retrieved from https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/jordan/climate-data-projections

- ↑ Al-Zyoud, S., Rühaak, W., Forootan, E., & Sass, I. (2015). Over Exploitation of Groundwater in the Centre of Amman Zarqa Basin—Jordan: Evaluation of Well Data and GRACE Satellite Observations. Resources,4(4), 819-830.

- ↑ Al-Zyoud, S., Rühaak, W., Forootan, E., & Sass, I. (2015). Over Exploitation of Groundwater in the Centre of Amman Zarqa Basin—Jordan: Evaluation of Well Data and GRACE Satellite Observations. Resources,4(4), 819-830.

- ↑ Al-Hanbali, A., & Kondoh, A. (2008). Groundwater vulnerability assessment and evaluation of human activity impact (HAI) within the Dead Sea groundwater basin, Jordan. Hydrogeology Journal,16(3), 499-510.

- ↑ Hadadin, N., Shatanawi, K., & Al-Weshah, R. (2014). Rainwater harvesting in Jordan: A case of Royal Pavilion at Amman Airport. Desalination and Water Treatment,1(11).

- ↑ Peacock, M., Audet, J., Jordan, S., Smeds, J., & Wallin, M. B. (2019). Greenhouse gas emissions from urban ponds are driven by nutrient status and hydrology. Ecosphere,10(3).

- ↑ "Greater Amman". Water Technology.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Klassert, C., Sigel, K., Gawel, E., & Klauer, B (2015). "Modeling Residential Water Consumption in Amman: The Role of Intermittency, Storage, and Pricing for Piped and Tanker Water". Water. 7: 3643–3670.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ Rosenberg, D. E., Howitt, R. E., & Lund, J. R. (2008). "Water management with water conservation, infrastructure expansions, and source variability in Jordan". Water Resources Research. 44: 1–11.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ "WADI MA'IN, ZARA & MUJIB WATER TREATMENT PLANT & CONVEYANCE PROJECT". Arab Towers Contracting Company.

- ↑ "Staged Climate Change Adaptation Planning for Water Supply in Amman, Jordan". Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management. 138.

- ↑ Baylouny, A. M., & Klingseis, S. J. (2018). Water thieves or political catalysts? Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon. Middle East Policy, 25(1), 104-123. doi:10.1111/mepo.12328

- ↑ Ladenhauf, J., & Liven, I. (n.d.). Water Shortage in Jordan. Retrieved from http://www.goethe.de/ins/jo/amm/prj/ema/far/whj/enindex.htm

- ↑ MercyCorps. (n.d.). Tapped Out: Water scarcity and refugee pressures in Jordan. Retrieved from https://www.mercycorps.org/research/tapped-out-water-scarcity-and-refugee-pressures-jordan

| This urbanization resource was created by Course:GEOG352. |