Course:EOSC270/2021/Commercial Whaling

The Threat of Commercial Whaling on Marine Ecosystems

What is the problem?

What is Commercial Whaling?

Among the overwhelming number of marine conservation issues is commercial whaling, which in recent centuries, has devastated whale populations and driven them close to extinction. To better visualize the impact of whaling, a 2017 study created population models of five species of commonly hunted Baleen whales using catch rates since 1890 to estimate future population trajectories up to 2100[4]. The results of the models depict mass depletion of blue, humpbacks, fins, and right whales to less than half of pre-exploitation sizes. Additionally, they predict difficulties in restoring whale stocks considering the naturally long lifespan and very slow reproduction rates unless hunting ceases and mortality rates drop[4]. The growing concern for conservationists is putting an end to ongoing whaling practices and trying to help populations recover from the damage that has occurred.

What human actions cause the problem?

The history of hunting whales dates as far back as 4,000 years ago when whales were once considered a sustainable and acceptable source of food, oil, and other valuable goods[1]. A major turning point was World War II which caused a commercial revolution involving vast technological advancements. This caused an exponentially increasing demand for oil which drove up the market value of whale blubber[3]. Advancements in harpoons, grenades, ship engines, and better mapping of the open oceans made it possible to greatly increase catch rates. For example, the sail powered vessel pictured in Norway in 1905 is comparatively much slower than the Japanese factory ship built just 30 years later. It also did not have the capacity to process whale kills onboard and thus kills had to be transported to docks and further broken down then[5].

Naturally, economically driven nations around the world began growing their whaling industries to compete for the now valuable resource in the open ocean which did not yet have territorial claims[5]. At this point, whaling was no longer a sustainable industry as it lacked sustainable practices and careful resource management. Ideally, fisheries and any industry involving a limited resource should have limits to how much can be extracted from its source at a given time. While the option may not remain, a more sustainable system might have considered each whale species population individually and avoided hunting beyond a threshold that maintains a stable population number[6]. Proper management would thus involve careful calculations of catch quotas and the risk for over-exploiting a species.

The secondary effect of commercial whaling are the unintentional whale casualties caused by whaling ships and debris. Some whales are lost from getting struck by ships or entangled in whaling debris and gear[7]. There is also evidence suggesting that the noise pollution from these ships cause stress, disorientation, and interfere with their acoustic signaling[8].

Where does the problem occur?

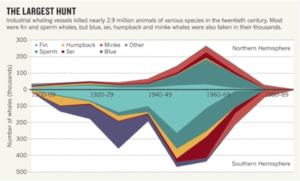

In 2015, first analysis of global catch data estimated that at least 2.9 million whales were killed in the 20th century alone[10]. The data also revealed a pattern in total catch of the most hunted species would quickly peak and then fall close to zero. The trend coincided with the species-level collapse of populations, reduced by up to 90%[10]. This trend is indicative of how efficiently commercial level whaling drives populations down to scarcity.

Even more jarring is that whaling in the 20th century has extracted the largest total biomass of any animal in human history[11]. Figure 1 reveals just how rapidly the hunting capacity of whaling vessels increased from 1940 to 1980. The severity of this issue goes beyond the endangerment of whale populations as they also play a large role in balancing the marine ecosystem and carbon cycle, for reasons that will be explained in the following sections.

How pervasive is the problem today?

In 1986, the International Whaling Commission, IWC, established a moratorium to prohibit whaling across global waters. While large-scale commercial fishing has since declined, the problem continues as Japan, Iceland, and Norway chose to act against international law and carry on whaling[12]. A portion of this hunting is attributed to a loophole in the moratorium in which operations for the specific purpose of scientific research may be permitted. This resulted in vessels displaying “Research” in overt lettering, as in the Nisshin Maru ship above.

As shown in figure 2, in the 2000s, Iceland and Norway have together killed 16,102 whales in the North Atlantic ocean and Japan has killed an estimated 15,613 whales in the Antarctic Ocean[13]. Casualties include many whale species such as Fin, Sperm, Humpback, Sei, Bryde’s, Minke, Grey, and Bowheads but it should be noted that these only account for killings directly reported to the IWC. Some studies comparing catch rates from different nations in the Pacific show evidence of dishonesty and unreliability of total catch reports and protected species may still be at risk[14].

How does this problem impact marine ecosystems?

How and why does it impact the identified ecosystems?

Large sea animals such as whales function as carriers of massive amounts of carbon in their bodies. When they die, that carbon is released back into the environment. As the whale carcasses sink, they also export the carbon to the deep sea [15]. The effects of whaling not only increase the number of whale deaths, but also contribute to an significantly increased carbon level in the atmosphere as the whales are killed on the surface so the carbon is released into the atmosphere instead of at the bottom of the sea. With the increased level of carbon, it will begin to impact the climate and ocean ecosystems where the whales live. When whales die, their carcasses sink to the bottom of the ocean, where the carbon is released, and the carcass will be eaten by detritivores such as crabs and sea stars that live at the ocean floor. Removing the whales causes a major effect on the marine species on the ocean floor that rely on the whale carcasses to survive. Whales contribute massively to the ecosystem through nutrient cycling, as they eat their respective prey in the deeper depths of the ocean and when they surface to breathe, they release their excrement. Their excrement is rich with phosphorus and other nutrients that will be consumed by the plankton which are then consumed by the marine animals that eat them, leading back to the whales and therefore forming the nutrient cycle of the ocean[16].

Are their unique characteristics of this habitat that make it vulnerable?

The impact of whaling is a major blow on the ocean ecosystem. The ocean is an essential part of the carbon cycle, being the largest carbon reservoir and absorbing 25% of carbon emissions from the atmosphere [18]. The carbon is controlled by a biological pump so that carbon is transferred from the surface to the deep ocean by the sinking of dead organic matter such as whale corpses. By affecting that part of the cycle, the ocean is not able to absorb as much carbon and more carbon will be present in the atmosphere. The ocean is also home to many marine species that will be affected by the whales and whaling. The animals that the whales prey on will begin to increase in number out of control as the whales will no longer be present to feed on them, and the detritivores that rely on the whale carcasses will also suffer. The nutrient cycle will also be affected as the whale excrement will not be redistributed and eaten by the plankton in the ocean.

What organisms does it impact?

As whales are the largest animals in the ocean, their impact involves almost all of the marine life found in the ocean. Whaling impacts not only the whales being targeted, but also the entire ecosystem that the whale affects. There are many different species of whales that are targeted, such as sperm whales, minke whales, narwhals and humpback whales. Not many animals prey on the whales, except sharks and orcas who sometimes attack and eat whales. When a whale dies and sinks to the deep ocean bed, their carcass becomes a feeding ground for many aquatic animals such as crabs and sea stars. The main source of the whales’ diet are also affected. For baleen whales, the main marine animals that are affected are krill. For toothed whales, the main marine animals affected would be fish and squid.

How and why does it impact this organism/s?

For the whales, they are obviously affected by the whaling industry as they are being targeted and killed for their meat and oil. Also, when the whales are killed due to whaling, their carcasses are not sunk to the deep sea and therefore the deep sea detritivores are impacted. Whaling has a major effect on the ecosystem as whales contribute largely to its nutrient cycle, not just through its excrement, but also because of its position in the ocean food web. As the whale population dwindles, the marine animals that are mainly their food will continue to rise in number. Baleen whales such as humpbacks eat large amounts of krill and toothed whales such as sperm whales eat large amounts of squid and fish. As their numbers are affected by whaling, the population of their prey will begin to rise.

Are their unique characteristics of this organism/s that make it vulnerable?

Whales are targeted as they each can provide significant resources in terms of meat, oil, and bone, so many are hunted down. As whales are large animals, the modern tools used in whaling are not always able to kill them immediately or humanely. If the whale managed to escape, the harpoons left in their body would eventually kill them, and as whales are long-lived animals that are slow to reproduce and difficult to monitor, there seems to not be a way to sustainably use them [21]. Due to this specific vulnerability, the impacts of whaling are far more serious than regular overfishing, as the recovery time for the whale population is significantly increased in order for them to return to pre-exploitation levels.

What is the extent of the problem?

What are the measurable ecosystem changes that have occurred?

The populations of many whale species have fallen dramatically from their pre-industrial whaling populations. Of all large whales, three are listed as Endangered by the IUCN: the sei whale, blue whale, and North Pacific Right whale, while the North Atlantic Right whale is listed as Critically Endangered. The Fin whale and the Sperm whale are also listed as Threatened by the IUCN, and many regional populations are considered to be endangered or have even been wiped out completely, as in the case of the Atlantic population of the Gray whale. Of all large whales, only the Minke whale has never been considered to be under any threat of extinction. The population of the North Atlantic Right whale in particular has been in a dire state in recent years, after centuries of whaling crippled their population, and ship strikes and entanglement continue to prevent recovery, driving them to the brink of extinction: it’s thought that only around 400 North Atlantic Right whales still live[22]. Other species have also seen dramatic declines, such as fin whales and blue whales, but not to the same extent.

What is the present status compared to the past?

Since the end of intensive commercial whaling in the 1970s, the outlook for the future of whales has been a mixed back. There have been some success stories: the humpback whale, notably, has seen a major recovery[23] and while its population remains well below its pre-whaling figures, it is no longer to be considered in danger of extinction by the IUCN, being delisted in 2008. Other species, such as the fin whale and blue whale, have also seen some recovery, but nowhere near pre-whaling levels, and are still considered endangered or threatened[24]. Yet more species, such the above-mentioned North Atlantic Right whale, are still facing severe struggles. Since whales are large animals that grow slowly and have long gestation times, threats posed by other sources, such as ship strikes[25] or fishing net entanglements. Three countries still practice some form of commercial whaling: Iceland, Norway, and Japan. The catch of the remaining commercial whaling industry is predominantly of the Minke whale, which is not currently considered to be endangered[26] However, Icelandic and Japanese whalers have taken some fin and sei whales, which are both Threatened according to the IUCN.

What is the prognosis for the future if we continue on our current trajectory?

While many whale species remain in severe danger, whaling in and of itself represents only a small fraction of the danger faced by large whales. In the countries where commercial whaling continues, demand for whale-based products has been decreasing, but many see whaling as a point of national pride, even if they themselves do not consume much whale meat or other products. In these countries, the whaling industry continues to receive generous government subsidies. These countries insist that their hunts are conducted in a sustainable manner, while critics have pointed to takings of some endangered fin whales (by Iceland) and sei whales (by Japan) and called into question the long-term sustainability of the industry, and there are concerns for specific whale populations in areas where whaling takes place.[27]

Given the impact, what are the solutions?

Recognition of the devastating impact whaling has had on the global whale population led to the formation of an international organization to combat the issue in 1946. This organization is named the IWC (International Whaling Commission) and is dedicated to protecting all whale species from overfishing in a socioeconomically viable way.[28] This includes the establishment of sanctuaries, limitations on the number of whales caught for scientific or commercial purposes, restrictions on hunting methodology and equipment, and protection of female whales accompanying calves as well as the calves themselves.[29]

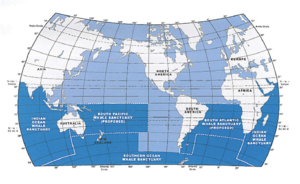

At present, the IWC has established two sanctuaries, one in the Indian Ocean (established in 1979), and one in the Southern Ocean, encompassing all of Antarctica (established in 1994). Extensive studies show that the population of numerous whale species is recovering remarkably fast. For Instance, a case study on Humpback whales conducted from Cape Byron shows an increase in Humpback whale sightings by 11.0% between the years 1998 to 2004.[30] This remarkable increase resulted in the proposal of two more sanctuaries, one in the South Pacific and one in the South Atlantic Ocean. With the addition of these two sanctuaries, it is likely that the whale populations will continue increasing at an accelerated rate.[31]

Furthermore, the IWC implemented an international moratorium on whaling, forbidding any whaling for commercial purposes. The success of this legal measure is evident in the numbers. Whilst in 1961, before the implementation of the moratorium, the total number of whales killed for any purposes was around 66,000, there was a drastic decrease in 1989 , after the moratorium was implemented, to only 326 whales killed.[32] The only issue is that in recent years, the number of whales killed began rising again. Even if the increase is only minor, the impetus behind the issue is reason for concern. Norway and Iceland have chosen to opt out of the moratorium and resume commercial whaling. Japan is also in the process of leaving the IWC to commence commercial whaling. In Japan's case it should also be noted that the country has worryingly high numbers of whales caught for scientific purposes even before leaving the IWC. The driving factor behind this decision is likely the extensive history of whaling is these regions, dating back as far as 4000 years. However, the countries that choose to leave the IWC are permitted to commence whaling only in their domestic waters, as international waters are still under the IWCs control. This limitation is playing yet another important role in whale preservation.[33]

Some Indigenous communities around the globe are still permitted to hunt whales in the interest of preserving Indigenous rites and cultures. However, this process is heavily monitored with restrictions regarding the age and species of whale, geographic location and methods used for the hunt. Local agencies are responsible for invigilating this process. For example, in Canada, the DFO (Department for Fisheries and Oceans) works together with indigenous communities in order to decide whether or not hunting specific whales poses a risk to conservation. The DFO also limits the weapons and boats used. In Canada, it is permitted to use small open skiffs, and handheld weapons only. This means the hunters are restricted to harpoons, rifles and shoulder guns.[34]

In conclusion, the IWC works with global and local partners in order to ensure the preservation of endangered whale species, as well as to support the overall increase in the number of whales in international waters. At the moment the statistics reflect the success of the implemented legal measures, however there is a need for constant adjustment and vigilance in order to maintain a positive trend.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bryce, Emma (February 22, 2020). "Why was whaling so big in the 19th century?".

- ↑ "Nisshin Maru". Vessel Finder. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Jackson, G (2019). "Whaling". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Tulloch, VJD; Plagányi, ÉE; Matear, R; Brown, CJ; Richardson, AJ (2019). "Ecosystem modelling to quantify the impact of historical whaling on Southern Hemisphere baleen whales". Fish Fish. 19: 117–137.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Avango, D.; Hacquebord, L.; Wråkberg, U. (2014). "Industrial extraction of Arctic natural resources since the sixteenth century: technoscience and geo-economics in the history of northern whaling and mining". Journal of Historical Geography. 44: 15–30.

- ↑ Morishita, J. (May 2002). "Resumption of Whaling and the Principle of Sustainable Use". Ship and Ocean Newsletter.

- ↑ "Whaling". Humane Society International. 2020, November 5. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Rolland, R. M.; Parks, S. E.; Hunt, K. E.; Castellote, M.; Corkeron, P. J.; Nowacek, D. P.; Kraus, S. D. (2012). "Evidence that ship noise increases stress in right whales". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279(1737): 2363–2368.

- ↑ McCarthy, N. (2019). "Whaling: No End In Sight". Statista.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Rocha, R. C.; Clapham, P. J.; Ivashchenko, Y. V. (2014). "Emptying the oceans: a summary of industrial whaling catches in the 20th century". Marine Fisheries Review. 76(4): 37–48.

- ↑ Cressey, D. (2015). "World's whaling slaughter tallied". Nature. 519(7542): 140–141.

- ↑ Swinbanks, D. (1987). "Japan disputes need for moratorium on whaling". Nature. 326: 732.

- ↑ "Total Catches". International Whaling Commission. 2019.

- ↑ Ivashchenko, Y. V.; Clapham, P. J. (2015). [doi:10.1098/rsos.150177 "What's the catch? validity of whaling data for japanese catches of sperm whales in the north pacific"] Check

|url=value (help). Royal Society Open Science. 2(7): 150177–150177. - ↑ Pershing, A; et al. (2010). "The Impact of Whaling on the Ocean Carbon Cycle: Why Bigger Was Better". The Impact of Whaling on the Ocean Carbon Cycle: Why Bigger Was Better. Explicit use of et al. in:

|last=(help) - ↑ Ratnarajah, L.; et al. (2014). "The biogeochemical role of baleen whales and krill in southern ocean nutrient cycling". PLoS One, 9(12). Explicit use of et al. in:

|last=(help) - ↑ Roman J, McCarthy JJ (11 October 2011). [doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013255 "The Whale Pump: Marine Mammals Enhance Primary Productivity in a Coastal Basin"] Check

|url=value (help). PLoS ONE 5(10): e13255. - ↑ Roy-Barman, M.; et al. (2016). [10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198787495.003.0008 "Marine geochemistry: Ocean circulation, carbon cycle and climate change"] Check

|url=value (help). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help) - ↑ Fallows C, Gallagher AJ, Hammerschlag N (April 9, 2013). ") White Sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) Scavenging on Whales and Its Potential Role in Further Shaping the Ecology of an Apex Predator". PLoS ONE 8(4): e60797.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ Darnis, G., Robert, D., Pomerleau, C.; et al. (November 2012). "Current state and trends in Canadian Arctic marine ecosystems: II. Heterotrophic food web, pelagic-benthic coupling, and biodiversity". Climatic Change 115, 179–205 (2012). Explicit use of et al. in:

|last=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Whaling". Humane Society International. 2020, November 5. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Pace, R.M; Corkeron, P.J.; Kraus, S. D. (2017). "State-space mark-recapture estimates reveal a recent decline in abundance of North Atlantic right whales". Ecology and Evolution. 7(21): 8730–8741.

- ↑ Zerbini, Adams, Best, Clapham, Jackson, Punt, A. N.; Adams, G.; Best, J.; Clapham; Jackson, J. A.; Punt, A. E. (2019). "Assessing the recovery of an Antarctic predator from historical exploitation". Royal Society Open Science. 6(10). Unknown parameter

|First name 4=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Branch Miyashita, T.A.; Matsuoka, K.; Miyashita, T. (2004). "EVIDENCE FOR INCREASES IN ANTARCTIC BLUE WHALES BASED ON BAYESIAN MODELLING". Marine Mammal Science. 20(4): 726–754.

- ↑ Laist, D. W; Knowlton, A.R.; Mead, J.G.; Collet, A. S.; Podesta, M. (2001). "Collisions between ships and whales". Marine Mammal Science. 17(1): 35–75.

- ↑ "Total Catches". International Whaling Commission.

- ↑ Song, Kyung-Jun (2011). "Status of J stock minke whales (Balaenoptera acutorostrata)". Animal Cells and Systems. 15(1): 79–84.

- ↑ "International whaling Commission". Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ↑ ARG, AUS, BRA, CAN, CHL, DNK, FRA, NLD, NZL, NOR, PER, ZAF, URS, GBR, USA. (1946, December 2). International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling. Washington , District of Columbia, United States of America: IWC.

- ↑ Paton, D. A., & Kniest, R. (2020). Population growth of Australian East coast humpback whales, observed from Cape Byron, 1998 to 2004. J. Cetacean Res. Manage., (3), 261-268. https://doi.org/10.47536/jcrm.vi.316

- ↑ Zacharias, M. A., Gerber, L. R., & David, H. K. (2004). Review of the Southern Ocean Sanctuary: Marine Protected Areas in the context of the International Whaling Commission Sanctuary Programme. n Sorrento: IWC Scientific Committee.

- ↑ Hurd, I. (2012). Almost saving whales: The ambiguity of success at the international whaling commission. Ethics & International Affairs, 26(1), 103-112. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0892679412000081

- ↑ Marrero, M. E., & National Geographic Society. (2012, October 15). Big Fish: A Brief History of Whaling. Retrieved January 29, 2021, from https://www.nationalgeographic.org/article/big-fish-history-whaling/

- ↑ Suydam, R., & George, J. C. (2021). Chapter 32 - Current indigenous whaling. In J. G. Thewissen, & J. C. George, The Bowhead Whale (pp. 519-535). Utqiaġvik: Academic Press.