Course:Carey HIST501/Project 1/Valentinianism

Appearance

Imagine that you were one of the bishops or heretics being summoned by the Emperor to be present at the great church councils. You want to spend every effort to discover all the heresies flowing around the Church. As preparation for the class, you will collect background information of major heresies/controversies in the early Church include the following

Biographical information of key leader(s) of the heresy/controversy

Valentinus (c.100 - c.160)[1]

- A second-century teacher and church leader[2]

- He was one of the first Christian philosophers[2]

- Was born around the year 100 in Phrebonis, an Egyptian town, and received a classical Greek education in Alexandria, the Hellenistic capital of the world.[3]

- After his conversion to Christianity, he studied under Theudas, whom according to tradition was a student of the apostle Paul, and Basilides, a Gnostic philosopher[4]

- According to Ireneaus, Valentinus almost won the contest to become the bishop of Rome.[5]

- It is believed that after Valentinus lost the contest of becoming bishop of Rome, he launched a teaching career in Rome in the late 130s. He was held in high esteem and several of his students went on to become important theologians themselves, most notably Ptolemy of Rome.[2]

Valentinianism

- According to Irenaeus' Adversus Haereses (ca. 180), Valentinians were considered the most dangerous of all the heresies.[6]

- The Valentinians were considered gnostics by heresiologists (what we might now called the 'proto-orthodoxy''), though elements of the Valentinian systematic theology centered on gnosticism, the Valentinians themselves didn't call themselves "Gnostics."[7]

- Valentinians considered themselves to be Christian and wanted to be accepted by the Church.[8]

- According to Tertullian, Valentinians were influenced by Eleusian mysteries but that they had created their own Eleusian dissipations.[9]

Time frame when the heresy “flourished”

- Valentinianism flourished around the mid-2nd Century, after he launched his teaching career in Rome.

- It is speculated that though there were many who opposed him with great fervor, many Christians of the time held him in high esteem. He was respected and considered a great teacher, orator and keen thinker.[2] His letters, songs, homilies and other writings were deeply praised for their profound philosophical analysis, literary beauty, and spiritual depth.[10]

- His interpretation of Christianity spread rapidly, and his teachings were split into two streams. A Western and Eastern variant of Valentinianism formed, and the Eastern variant survived for centuries.[10] In the late fourth century we still hear about Valentinians in Syria, despite this Eastern variant experiencing persecution from the proto-orthodoxy.[6]

Context that gave birth to the heresy/controversy

- In the first centuries CE a standard education model was for a school to be formed around an authoritative teacher, this was also true of Christianity. Gnostic communities also had philosophical schools. In Antiquity philosophical schools were always religious communities as well, in which tribute was paid to the founder of the philosophical movement to which the school belonged.[8]

- For centuries the only knowledge of the Valentinian belief system was through its patristic opponents. Irenaeus, Tertullian, and Clement of Alexandria all wrote in opposition to the Valentinian gnostic belief system.[6][10]

- Valentinus was the first to attempt to make a systematic, philosophical, and theological unified theory of Christianity.[10]

- It's important to note that Valentinus was trying to solve a highly complex theological/philosophical problem that early Christians were left with due to their conviction of Jesus as the Messiah. The problem had to do with the Jewish Messianic expectations. The theological/philosophical problem that faced early Christians is that Jesus did not defeat worldly evil, nor did he set up a physical kingdom with Jerusalem at the center of it. Early Christians were able to solve this issue by focusing not on a worldly defeat of evil, but rather Jesus the Christ's victory was a defeat of evil spiritually and metaphysically. This shift in Christ's victory meant that Christians were no longer tied to a specifically Jewish conception of what Messiah meant. In rejecting the specific Jewish conceptions of the Messiah, early Christians cleared up what they didn't believe but they didn't sort out what they did believe.[10]

- Valentinus sought to make sense of Christ's salvific role by combining Judeo-Christian teaching with Hellenistic philosophy and mythology.[10]

Central beliefs

Gnosticism

- Though Valentinians didn't call themselves Gnostics, the philosophical/theological belief system was profoundly gnostic. "Gnosis is a personal existential certainty: I come from God, I partake in his essence, I will return to him."[8] For Valentinians, salvation was not the result of faith, but rather liberation and salvation was attained through knowledge of his or her divine essence.[10]

- "Gnostics were not concerned with the truth of the myth but with the reality of liberation from the grasp of evil powers. What the gnostics sought was not rational truth but existential certainty.[8]

- The Book of Thomas (NHC II, 138, 16-18) says: A person who has no knowledge of himself knows nothing, but who knows himself has also gained knowledge of the depth of All![8]

Cosmic Mythological Framework for Valentinianism

- It must be stated that the system of belief for Valentinianism is highly complex.

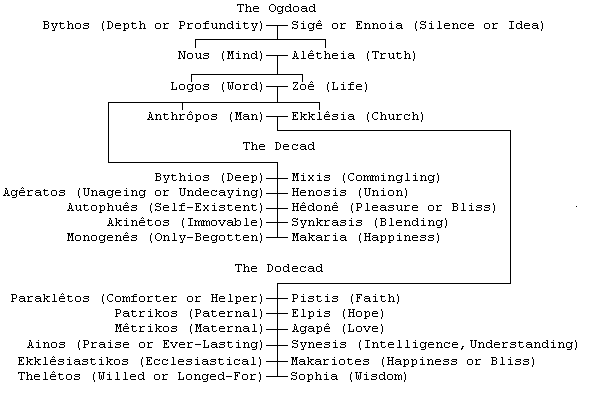

- The Father or Bythos - is the single principle beyond all comprehension. It is from the Father that the Aeons who along with the Father comprise the Pleroma.

- In Western Valentinianism, the Pleroma is comprised of 30 Aeons that are organized in pairs. (The image attached is a representation of the Western Valentinian understanding of the Pleroma.) The Eastern variant of Valentinianism doesn't limit the exact number of Aeons.[10]

- The final Aeon that the Father creates is Sophia (Wisdom). Sophia according to gnostic myths is the one who falls in her attempt to grasp the totality of the Father, she fails and is cast out of the Pleroma.[10][8] The fallen Sophia becomes the world creative power.[11]

- Outside of the Pleroma, Sophia ends up creating the psychical and material world out of arrogance and ignorance and trapped divine sparks within the world.[2][8]

- The Aeons in the Pleroma hear Sophia's repentant cries and produce a Saviour, the Christ figure who heals and redeems her.[8][10]

- As Sophia is experiencing salvation, she expresses pure joy which gives rise to divine sparks that are connected back to the Pleroma.[10]

- "The Gnostics are children of Sophia; from her the heavenly seed, the divine spark, descended into this lower world, subject to the Heimarmene (destiny) and in the power of hostile spirits and powers; and all their sacraments and mysteries, their formulae and symbols, must be in order to find the way upwards, back to the highest heaven."[11]

- Valentinians believe that the Saviour descended to the world in the form of Jesus to conquer temptation and death. Salvation for Valentinians is not the result of faith or belief in this Saviour, but rather it is special knowledge (gnosis) of the origin and flawed development of reality that liberates a person from the material and the psychical world and ushers them into the pure spiritual world of the Pleroma.[10]

- "In most of the Gnostic systems reported by the church Fathers, this enlightenment is the work of a divine redeemer, who descends from the spiritual world in disguise and is often equated with the Christian Jesus. Salvation for the Gnostic, therefore is to be alerted to the existence of his divine pneuma and then, as a result of this knowledge, to escape on death from the material world to the spiritual."[12]

The Practice of Sacraments

- The ancient world was saturated in magic. For many Gnostics, rites like baptism were practiced as the means of experiencing the supersensory world. While most non-gnostic Christian literature rejected the practice of magical rituals, the sacraments in the early Church "had an almost magic significance: baptism really washed away previously committed sins and the Eucharist really allowed people to share in the body of Christ and thus in his resurrection." We know "from various sources that ordinary believers called in magicians and consulted astrologers for all kinds of purposes." Valentinians who largely considered themselves Christians may not have practiced Christian rituals in a magical way, but most likely used these ecclesiastical sacraments as "theurgic rites for uniting the soul with God."[8]

- At the center of Valentinian ritual was what Valentinus called the "Bridal Chamber." The Bridal Chamber was essentially the practice of baptism and anointment that bestowed upon the recipient redemption. It was believed that the act of baptism united and actualized a person's soul with an angel that exists in the Pleroma.[8]

Opponents to the heresy/controversy and/or church council which dealt with the heresy/controversy

- According to Rodney Stark, though the Valentinians were rejected by the proto-orthodoxy, they were not persecuted. Stark speculates that the early church did not persecute heresy simply because it lacked the means to do so.[13]

- Valentinus nor his followers were officially condemned, heresiologists such as Justin Martyr, Irenaeus and Tertullian however, labelled Valentinus and his teachings heretical.[3]

- "Constantine 'directed his most ferocious rhetoric' not against pagans, but against Christian dissidents: Donatists, Arianists, Valentinians, Marcionites, and the 'Gnostic' schools. However, Constantine's rule was one that stressed peaceful pluralism.[13]

Impact of the heresy/controversy to the Christian Church

- In studying Valentinianism, it becomes clear that this heresy may have had broad appeal to many within the Roman empire as Valentinus was attempting to make sense of Christ's salvific role by combining Judeo-Christian teaching with Hellenistic philosophy and mythology.[10]

- "The church had reason to be afraid of Greek philosophy and pagan literature. Pagan religion permeated classical literature, and this simultaneously religious and philosophical framework tended to distort key Christian convictions. Poorly informed Christian converts often faced a choice between clever, eloquently defended heresy and a seemingly ignorant orthodoxy.[14]

- Valentinians worshiped in congregations made up of various different kinds of Christians, but then also held meetings that were reserved for Valentinians. They seemed to have been well integrated into the Christian mainstream.[2]

- Perhaps one reason why Valentinianism was difficult to root out from the early Christian church is due to the fact that Valentinians did not adhere to the ascetism of classic Gnosticism. Valentinians married, had families, and worked ordinary jobs. Though they participated in worldly pursuits, they deemed worldly pursuits less important than spiritual ones. "Like the Stoics, they strove to prevent themselves from becoming emotionally attached to earthly delights even while partaking in them."[2]

References

- ↑ "Valentinus". Glorian. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 McCoy, Daniel. "Valentinus and the Valentinians". Gnosticism Explained. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Valentinus". Early and Medieval Christian Heresy. 2015.

- ↑ Lewis, Nicola Denzey (2013). Introduction to "Gnosticism:" Ancient Voices, Christian Worlds. Oxford University Press. p. 63.

- ↑ Lewis, Nicola Denzey (2014). Introduction to "Gnosticism:" Ancient Voices, Christian Worlds. Oxford University Press. p. 19.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Markschies, Thomassen, Christoph, Einar (2020). "Valentinianism: New Studies". Nag Hammadi and Manichean Studies. 96: 1 – via BRILL.

- ↑ Brakke, David (2010). The Gnostic: Myth, Ritual, and Diversity in Early Christianity. Harvard University Press. pp. 31–35.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 Van Den Broek, Roelof (2013). Gnostic Religion in Antiquity. New York: Cambridge. pp. 91–137.

- ↑ Tertullianus, Quintus. Tertullians - Against the Valentinians. p. 6.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 Sledge, Justin (May 21, 2021). "Valentinian Gnosticism - The Earliest Systematic Philosophy & Theology of Christianity". Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Valentinianism". Wikipedia. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ↑ Marshall, Millard, Packer, Wiseman,, I. Howard, A.R., J.I., D.J. Eds. (1996). New Bible Dictionary. UK: IVP. p. 416.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Stark, Rodney (2011). The Triumph of Christianity. New York: Harper Collins. pp. 175, 178.

- ↑ Shelley, Bruce L. (2020). Church History in Plain Language. Michigan: Zondervan. p. 93.