Course:CONS370/Projects/The Wet’suwet’en Nation, British Columbia, Canada and the Coastal GasLink pipeline: history, jurisdictional issues, positions, alliances and potential outcomes

In 2012, planning began by TC Energy Corporation for the construction of a 670 km liquid natural gas pipeline through northern British Columbia, Canada[1][2]. The pipeline project came to be named the Coastal GasLink pipeline and is expected to cost approximately CAD 6.6 billion dollars to construct[1]. The proposed pathway of the pipeline passes through the traditional territories of a number of First Nations[3]. While many elected Band Council governments and communities and First Nations support the construction of the project, many, particularly hereditary leaders, are also concerned or opposed, including the hereditary leaders of the Wet'suwet'en Nation who occupy a traditional territory of over 22,000 square kilometers in northwestern British Columbia through which the proposed pipeline would pass[4]. Beginning in 2019, civil disobedience and protests have occurred nationwide in support of the Wet'suwet'en who have declared the actions of TC Energy Corporation, the Canadian and Provincial governments, and the RCMP to be in direct contravention of their traditional laws and Aboriginal title[5].

Description

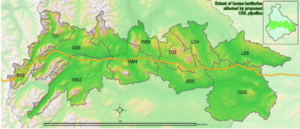

The Coastal GasLink pipeline is a natural gas pipeline that is under construction in British Columbia. The pipeline will be approximately 670 kilometers in length. The route starts in Dawson Creek and travels across central BC to reach the coast at Kitimat where the gas will then be exported to international markets[6]. This pipeline project has been controversial since its inception in 2012 and is under significant scrutiny from external stakeholders. The proposed route of the pipeline transects many First Nations traditional territories, and the most vocal opposed rights-holders have been the hereditary leaders and some (but not all members of the) Wet’suwet’en Nation. The pipeline would run through 190 kilometers of Wet’suwet’en traditional territory, which will impact the land and resources that the Wet’suwet’en people see themselves as protectors and stewards of[7]. Although this pipeline has been approved by the band council leadership of the Wet’suwet’en, the hereditary chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en people have different views towards the pipeline and are opposed to its construction.

Administrative arrangements

Hereditary Governance System

The traditional governance system of the Wet’suwet’en is the hereditary governance system[4]. This system remains today the Wet’suwet’en people’s preferred expression of legal power over their traditional territories, some 22,000 square kilometers in northern British Columbia[4]. Furthermore, the hereditary governance system is the recognized source of legal power over Wet’suwet’en traditional territory and the seat of aboriginal title according to the Supreme Court of Canada[8].

The hereditary governance system is composed of five hereditary clans, subdivided into thirteen houses, with each house being represented by a head chief and potentially several wing chiefs[4]. To become a chief it is not necessary to be the descendant of a current or past chief. In this sense, the system is not strictly hereditary in the common understanding of the word. Rather, to become a chief, an individual must be chosen by the community to fill the role “based on the deportment and merit of the adult candidates”[4], whether or not they have previously held the position. Hereditary chief titles are passed legally between individuals through ceremonies attended by the other chiefs. however the laws outlining the transfer of power between individuals varies between houses.

Although the different houses share a common cultural identity, it is important to note that different houses have different laws, customs, and territorial rights. It is not correct to view the Wet’suwet’en as a monolith under a single governance system, with singular beliefs and objectives. It is not appropriate to assume that the views of one house represent the views of another. Further, it is not appropriate to dismiss the views of a minority of houses because the majority have a stronger voice. The culturally and legally appropriate approach is to recognize the legal independence of each house and to treat them all as separate entities requiring separate consultation and consent when their separate territories are involved[9].

With respect to the Coastal GasLink pipeline project that is proposed within the traditional territory of the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs, disagreements over support for the project exist between houses and chiefs. As of January 12th, 2020, of the 9 hereditary chiefs (4 positions were then vacant), 8 are opposed to the project, and 1 holds a neutral position[4]. It must be noted however, that there has been significant in-fighting within the Wet’suwet’en hereditary system between current and former chiefs who had supported the project prior to their potentially illegal removal from power. It is also noted that some of these former chiefs had accepted tens of thousands of dollars from Coastal GasLink and colonial governments in order to gain their support for the project[4].

Band Council System

The band council system is a colonial governance system that was imposed upon the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada, including the Wet’suwet’en, via the Indian Act (1876)[10]. The system’s intent was to replace traditional governance systems in Indigenous communities for the purpose of displacing the inherent authority of Indigenous leaders and eroding their culture and belief systems[11].

The authority of band councils applies only to Federal reserve lands, the boundaries of which do not represent the traditional territories of most Indigenous peoples, or the Wet’suwet’en specifically[9]. Approximately 2800 Wet’suwet’en are represented within this system by five elected band councils[4]. Another approximately 400 Wet’suwet’en live outside Federal reserve lands, and therefore receive no representation under this system. Within the Canadian legal framework, band councils are often the organization that is consulted by provincial and federal governments for project approvals because they are far more likely to cooperate due to they being largely funded by the federal government[10]. This is not only an impediment to Reconciliation, but also does not respect the rights of Aboriginal People to self-determination. Furthermore, consultation with band councils instead of traditional governance systems ignores the presence of any Aboriginal People not living within Federal reserve lands, or not considered a status Indian.

All five Wet’suwet’en band councils voted to approve the Coastal GasLink pipeline project[4]. It must be noted that the band councils do not represent all Wet’suwet’en or all interests of the Wet’suwet’en, and only have the authority to approve projects within Federal reserve lands. Beyond the reserves, within the traditional territory of the Wet’suwet’en, the band councils do not have jurisdiction[4].

Legal context

Delgamuukw (1997)

Chief Delgamuukw was one of many Wet’suwet’en hereditary chief plaintiffs in a 1997 Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) case representing the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan people in claiming Aboriginal title over approximately 58,000 square kilometers of their traditional territory[8][10]. The trial was dismissed over changes to the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan pleadings partway through the trial[8]. Despite this, the ruling created legal precedence for the acceptance of oral tradition as legal evidence in Canadian courts[8] and established for the first time the legal definition of Aboriginal title and how Indigenous people may exert it[8][9]. According to the SCC’s comments, Aboriginal title is the right to territory, including jurisdiction. It was not decided in this case where, specifically, Aboriginal title exists for the Wet’suwet’en - it simply asserted that it exists, and was not extinguished by assertions of sovereignty by the crown at the time of the signing of the Oregon Boundary Treaty in 1846[8]. Despite this, the SCC acknowledged through these proceedings that the hereditary chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en were the holders of Aboriginal title and thereby the recognized legal power on Wet’suwet’en traditional territory[10][4]. The government of British Columbia will not, however, relinquish control of the Wet’suwet’en traditionally territories until the time when they are able to demonstrate the extent of their traditional territories in court by meeting the requirements set out by the SCC following the Delgamuukw decision[8].

While many interpret the SCC’s response to this case as a step forward for relations between the Wet’suwet’en and colonial governments, it made several comments in its decision that make clear its continued opposition to granting full territorial rights to aboriginal communities or the Wet’suwet’en. One such comment states that “Aboriginal rights are a necessary part of the reconciliation of aboriginal societies with the broader political community of which they are part; limits placed on those rights are, where the objectives furthered by those limits are of sufficient importance to the broader community as a whole, equally a necessary part of that reconciliation”[8]. The implication of this comment is that, in the eyes of the Canadian judiciary, economic development for the betterment of Canadians justifies the infringement of Aboriginal title. To be clear, it is the view of the SCC that developments such as the Coastal GasLink pipeline are to be forced through the traditional territory of the Wet’suwet’en whether or not their Aboriginal title is legally and/or spatially defined.

Another comment by the SCC following this trial calls to question the legal basis of the crown’s assertions of sovereignty over the traditional territory of the Wet’suwet’en. The SCC briefly quotes the Constitution Act: “the rule of law is… preclusive to arbitrary power”[8]. This assertion, designed to preclude the use of arbitrary power, directly contradicts the crown’s arbitrary assertions of sovereignty over lands their people had never even set foot in at the time of the signing of the Oregon Boundary Treaty. According to lawyer John Borrows, “the Court has not articulated how (and by what legal right) assertions of crown sovereignty grant underlying title to the crown or displace Aboriginal governance"[8]. This interpretation of the Constitution Act invalidates the crown’s sovereignty assertions over Wet’suwet’en traditional territory. Despite not having legal justification for their sovereignty assertions, the government of British Columbia and Coastal GasLink continue to operate with relative legal impunity.

UNDRIP and Bill C-41

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007) outlines the rights of Indigenous peoples around the world and has been signed by Canada[12]. The contents of the declaration will be fully integrated into the laws of British Columbia in the coming years, as dictated by SBC 2019, c 44, formerly Bill C-41 (2019): “This Bill requires the government to take all measures necessary to ensure the laws of British Columbia are consistent with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples”[13]. Once the full intent of Bill C-41 is realized, the Wet’suwet’en and other Indigenous peoples’ power within the Canadian legal system to freely fight or endorse projects such as the Coastal GasLink pipeline may become more balanced.

Despite the provincial government’s expressed intent to uphold the rights of indigenous peoples, including the Wet’suwet’en, their actions with respect to the proposed Coastal GasLink project remain in direct contravention of several articles contained in the declaration.

UNDRIP Article 18 states give the Wet’suwet’en “the right to participate in decision-making in matters which would affect their rights, through representatives chosen by themselves in accordance with their own procedures, as well as to maintain and develop their own indigenous decision- making institutions”[12]. This article stands to provide the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs with further legal recognition of their status as the legal decision-makers in their traditional territories.

UNDRIP Article 26 makes three important assertions:

“1. Indigenous peoples have the right to the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired.

2. Indigenous peoples have the right to own, use, develop and control the lands, territories and resources that they possess by reason of traditional ownership or other traditional occupation or use, as well as those which they have otherwise acquired.

3. States shall give legal recognition and protection to these lands, territories and resources. Such recognition shall be conducted with due respect to the customs, traditions and land tenure systems of the indigenous peoples concerned"[12].

This article gives legal right and title to IP over their traditional territories, although it is not clear whether or not this article nullifies the SCC requirements for proof of Aboriginal title.

UNDRIP Article 32 makes 3 further assertions regarding the rights of the Wet’suwet’en people’s right to self-determination:

“1. Indigenous peoples have the right to determine and develop priorities and strategies for the development or use of their lands or territories and other resources.

2. States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, particularly in connection with the development, utilization or exploitation of mineral, water or other resources.

3. States shall provide effective mechanisms for just and fair redress for any such activities, and appropriate measures shall be taken to mitigate adverse environmental, economic, social, cultural or spiritual impact”[12].

Under this Declaration, with respect to resource development, the state is required to acquire free, prior, and informed consent from the Wet’suwet’en’s own representative institutions (hereditary chiefs or otherwise as they may decide) before approving any project affecting their lands or territories[12]. Given that the Coastal GasLink pipeline passes through Wet’suwet’en traditional territory, which is legally represented by the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs who have not given consent for the project to proceed, the provincial government and Coastal GasLink’s actions are in direct contravention of this article.

Affected Stakeholders

Affected stakeholders are defined as businesses, individuals and groups who hold legal rights and are directly affected, positively or negatively, by the Coastal GasLink pipeline project through the actions, objectives and policies enacted by proponents of the pipeline.

There are more affected stakeholders than mentioned on this page, but the following are the major players.

TC Energy Corporation - Coastal GasLink

TC Energy, formally known as TransCanada Energy, is a corporation that owns pipelines across North America, serving Canadian, US and Mexican markets[14]. Their pipelines lead from nearly all natural gas basins in North America, including Alberta, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Quebec and numerous US and Mexican States [14].

Coastal Gaslink is owned and operated by TC Energy Corporation [2]. TC Energy, backed by five petroleum corporations as partners (LNG Canada, Korea Gas Corporation, Mitsubishi, Petro China & Petronas), was selected for this project in June of 2012 by LNG Canada to take the lead in design, building, negotiations and operations of the pipeline [2]. The pipeline will create opportunities to expand Canadian natural gas exports to global markets [1]. In 2018, $6.1 billion of Canadian natural gas was exported, with the US as the sole purchaser [14]. The Coastal GasLink pipeline has huge potential to bring big dollars to its partners and investors. Backed by the provincial and federal governments of Canada, and financing from their partners, TC Energy has the power and desire to build this pipeline, regardless of their ethical and social responsibility to respect the rights and wishes of Aboriginal Peoples whom they negotiated agreements with.

The Canadian Federal and Provincial Governments

In 2018, Canada was the 4th largest producer and 6th largest exporter of natural gas in the world and is projected to be able to sustain current production levels for up to 300 years[14]. Between 2016-2018, the oil and gas industry contributed, on average, $108 billion annually to Canada’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), i.e. 5.6% of total GDP; $101 billion in revenue for corporations and Canadians; and an estimated $8 billion in revenue annually in taxation and royalties to the Canadian government[15]. The oil and gas industry is the largest contributor of all other Canadian industries[15]. Given the financial inputs and economic stimulus, the government institution as a whole is strongly biased towards development projects in this sector, as well they have the power and authority to facilitate the pipeline project.

The federal government has a constitutional responsibility to protect the rights of its people. Aboriginal Peoples especially need protection as their rights have only recently been recognized and are threatened by provincial government and energy corporations. The Expropriation Act of 1985 gives the government the means to take land, as the expropriating authority, under the act without the consent of the owner, guardian, or in this case, the First Nation [16]. The Expropriation Act gives the government of Canada and British Columbia the power to seize land for development, typically for energy, and that the ill-action towards a small group is justified by the significant benefit the general population will receive. There are caveats, such as the Musqueam Reconciliation, Settlement and Benefits Agreement Implementation Act which protects the Musqueam Nation from these laws, but the Wet’suwet’en are not exempt[16]. Acts such as these give the government total control to back and support development project such as Coastal GasLink.

Although Expropriation measures have not yet been used, B.C. Supreme Court judge, Justice Marguerite Church, extended an interlocutory injunction order on behalf of Coastal Gaslink following the placement of blockades on Wet'suwet'en territory to prevent Coastal Gaslink from beginning construction[17]. An interlocutory injunction is a court order that restrains a party from engaging in certain acts for a predetermined amount of time, typically until the court has finalized decisions in the lawsuit or trial [18]. The injunction called for the removal of all blockades and other obstructions that disrupt any worksites associated with Coastal Gaslink [19]. Throughout this dispute, the Wet’suwet’en felt strongly that the provincial and federal law had failed to protect their land, their people and their interests which bolstered their need to protect themselves as it is their responsibility to ensure the health of their territory for future generations as has been done for centuries preceding [20]. The Wet'suwet'en resisted the injunction order which led the government to use force against the protestors. RCMP (Royal Canadian Mounted Policy Force) physically removed and arrested protestors, prompting more protests throughout the country in solidarity with the Wet'suwet'en [21].

Wet'suwet'en First Nations

The Wet'suwet'en are stewards for their lands and are responsible for the protection of their traditional territories to ensure its health and longevity for future generations, as has been done by past generations [7]. Their lands are unceded, meaning they never surrendered their title to colonial settlers or government [22]. The Wet'suwet'en culture and way of life is threatened by successive development projects in their territory for agriculture, forestry, mining and pipelines [22], irrespective of their rights described in section 35 of the Constitution Act of 1982 [23]. By law the government must engage with First Nation stakeholders prior to development. Although the province of British Columbia did consult with the Wet’suwet’en, the Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs argue that consultation with the elected council is insufficient as the hereditary council system is their traditional governance system [24].

In Canada, Aboriginal rights are inherent and protected under the Constitution Act. Aboriginal title, along with the associated rights, are intended to protect Aboriginal Peoples whether or not there is an established treaty, as is the case for the Wet'suwet'en. Unfortunately, the Constitution does not explicitly describe what rights Aboriginals hold, but does say they have the right to practice customs integral to their distinct cultural identity, such as connection to territory, and that specific activities may be directly linked to specific areas within their territory[23]. In 1997, the Hereditary Chief of the Wet’suwet’en argued along side hereditary Chief Delgamuukw of Gitxsan First Nation, that their oral history is proof of prior occupation and long-standing control of their respective territories. Although they lost the case, it set precedence for territorial claims and gave way to better protection measures within Aboriginal title[25]. The trial resulted in Aboriginal title to mean right to the land itself, not just the right to subsist on natural resources like meat and plants, and that aboriginal title was never extinguished during colonial settlement[25].

BC, in November of 2019, passed Bill 41, Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, which is modeled from UNDRIP[26]. This legislation describes appropriate government conduct when engaging Aboriginal Peoples, such as respect and affirmation of their institutions and customs [26]. That being said, the Canadian governments are continuing to pursue the pipeline construction although they no longer have consent from the Wet'suwet'en. The Wet'suwet'en Chiefs claim that neither the federal nor provincial governments have agreed to meet to address concerns following the injunction order for the blockades to be removed[17] which lead them to contacting the United Nations Office of the Commissioner of Humans Rights [27]. Following an assessment, the UN representative called for the RCMP to stand down and to stop forcibly remove people from their territorial lands as free, prior and informed consent was not established [28]. As RCMP violence towards protestors at blockades escalated during the winter of 2020, UN committee of human rights described their actions as a “disproportionate use of force, harassment and intimidation by law enforcement officials against Indigenous peoples who peacefully oppose large-scale development projects”[28].

While the Wet'suwet'en may have rights and title to control their lands and that the law requires government to engage with First Nations in meaningful ways prior to development, it appears the Government is not acting on the legislation. The UN involvement as well as Wet'suwet'en demonstrations have not lead to re-negotiations nor alternative plans, which shows that the the UN does not have over-riding power vis-a-vis sovereign authorities. However Wet'suwet'en protests are supported by other less influential parties, such as protest demonstrations across the country.

Other Communities

Coastal Gaslink, alongside the Province of British Columbia Minister of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation arm, negotiated agreements with 20 First Nations in BC whose territory the pipeline route passes through and supporting LNG facilities[3][29]. The agreements are varied between nations, depending on degree of development required and certain elements, such as culturally significant areas or ecologically sensitive forests. The intent of the agreements is to foster long-term working relationships between the First Nation and to share benefits, as negotiated, by the building of the project[30]. Agreements include the permission to build the pipeline through their territory as well as investment and economic opportunities, defined as benefits by the province and Coastal Gaslink[3][30]. Examples of benefits are training opportunities for band members with long term careers available, and a stable revenue stream for respective First Nation which will increase economic stimulus into the community in the form of business development and increased investment power[31]. The Skin Tyee First Nation, for example, is to receive $2.3 million from Coastal Gaslink once 10 km of pipeline has been laid in their territory [32].

The 20 consulted First Nations hold the same rights as the Wet'suwet'en within Canadian and provincial law, though specific land claims and affiliated rights vary between nations. They have low influential power over the project as federal involvement supersedes them.

The 20 communities with agreements are as follows[3]:

- Kitselas

- Haisla

- Witset

- Skin Tyee

- Wet’suwet’en

- Nee Tahi Buhn

- Cheslatta

- Yekooche

- Stellat’en

- Burns Lake

- Nadleh Whut’en

- Nak’azdli Whut’en

- Saik’uz

- Lheidi T’enneh

- McLeod Lake

- West Moberly

- Saulteau

- Halfway River

- Blueberry River

- Doig River

Interested Outside Stakeholders

Interested outside stakeholders are social actors who have vested interest in the outcome of the project, but are outside of the communities directly affected. These social actors may be externally impacted in some ways by the actions of and decision made by the operating authority, in this case, Coastal Gaslink. Outside stakeholders may be for or against the building of the pipeline, for example, those who highly value the integrity of Northern BC’s ecosystems may be against the project, while a person who may benefit from a job created by the pipeline may advocate.

Protests

From the onset of the project, there has been a staunch divide in opinion and tension. On February 6, 2020, the RCMP arrested 28 land defenders at blockades within the Wet'suwet'en territory[33]. The RCMP's involvement and forceful actions prompted protests across the country in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en [21]. Protesters blockaded rail lines, ports, legislative buildings and busy intersections to gain the attention of Canadian decision makers and began a discourse to strengthen the voices of the Wet’suwet’en[21]. Protestors spoke of unjust action by the federal and provincial governments towards the Wet'suwet'en and that investments into fossil fuels are not for the best interest of Canadians today or in the future [34]. Protests continued across the country into early March of 2020 but dismantled following social distancing guidelines instated due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Discussion

The mission of the Wet’suwet’en Nation and their peoples are to have their rights and title to their traditional territory recognized by law, “to ensure responsible jurisdiction of the resources for equitable and sustainable use, and to ensure a government model based upon the solid foundation of our hereditary system”[7].

Critical Issues Timeline

December 31, 2019: The Supreme Court of BC grants an injunction for Coastal GasLink which calls for the removal of obstructions on all roads, bridges, and worksites that Coastal GasLink will use[19].

January 1, 2020: The Wet’suwet’en Nation gives Coastal GasLink an eviction notice, this states that the company and workers are trespassing on their traditional, unceded territory[19].

January 30, 2020: The Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs agree to seven days of meeting with the province for negotiations. The intentions of these talks were to de-escalate the conflicts between the Wet’suwet’en and Coastal GasLink[33].

February 6, 2020: The RCMP move onto Wet’suwet’en territory to uphold a court injunction and make multiple arrests that would allow for construction of the pipeline to resume. In response to the arrests members of Mohawk communities begin rail blockades between Montreal, Toronto, and Ottawa[19].

February 7, 2020: Via Rail stops service along the blockaded routes and additional protesters begin demonstrations at ports in Vancouver and Delta, BC[19].

February 8, 2020: The RCMP extends the exclusion zone in Wet’suwet’en territory. This is seen as a violation of Wet’suwet’en law, Canadian law, and of UNDRIP[5].

February 10, 2020: RCMP makes more arrests of protesters and Unist’ot’en matriarchs. Blockades, occupations, and protests break out all across Canada in support of the Wet’suwet’en people’s actions[5].

February 12, 2020: The exclusion zone created by the RCMP is lifted while blockades, protests, and occupations continue across the country[5].

February 13, 2020: Via Rail and CN Rail shut down. BC Premier John Horgan agrees to meet with the hereditary chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en[5].

February 18, 2020: A debate is held in the house of commons in which the Liberals push for continued dialog with the First Nations. Wet’suwet’en chiefs declare they will not negotiate until their territory is demilitarized[19].

February 20, 2020: The Minister of Public Safety announces the removal of RCMP from Wet’suwet’en territory with a condition that the Wet’suwet’en keep the road clear and adhere to the court injunction, the Wet’suwet’en reject this offer[19][5].

February 21, 2020: Justin Trudeau declares that injunctions must be followed, and blockades must be removed. The Wet’suwet’en chiefs and Mohawk leaders demand a full retreat of RCMP from the territory[19].

February 22, 2020: Protests and blockades remain in defiance of governments demands[5].

February 24, 2020: Mohawk territory is raided by the police and 10 people are arrested. This expands the protests around the country[5].

February 27, 2020: RCMP agrees to ending patrols in Wet’suwet’en territory and Coastal GasLink work goes on a two-day break, allowing for discussions between the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs and the provincial and federal governments[5].

March 1, 2020: Provincial and federal governments and the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs reach a tentative deal, but the deal must be discussed by the Wet'suwet'en community before approval. The deal doesn’t directly address the controversy around the Coastal GasLink pipeline[35].

Relative Successes and Failures

Successes

- One significant success for the Wet’suwet’en Nation is in challenging this issue of territorial rights and bringing national and international attention to this important case. Protests, occupations, and blockades were taking place all across Canada as a way for people to show support for the Wet’suwet’en Nation and fight for the rights of all First Nations. Examples of support for the Wet'suwet'en are the protest that took place in downtown Vancouver[36] and the Via Rail blockades in Ontario[37].The outcomes of this scenario will have a larger reaching impact throughout BC, Canada, and likely the rest of the world.

- Another success involving both the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs and the Provincial/Federal governments was the ability for the three parties to come together and reach a tentative deal to de-escalate the situation around the protests and blockades[35]. Although the details of the deal are not currently available and have yet to be fully approved by the Wet'suwet'en, the fact that the parties were able to reach some consensus is a good starting point. It is unlikely that this issue is coming to a close as the deal doesn't fully address the controversy.

Failures

- One failure of the Provincial and Federal governments was the failure to recognize Wet’suwet’en territorial rights on the basis of the Delgamuukw decision. Under the Delgamuukw decision, aboriginal title for the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs was said to have existed. however the Federal and Provincial governments will not legally give up control of the lands in the absence of a lengthy court trial to determine the extent of their traditional territories and only in the event that that trial were to uphold Wet’suwet’en Aboriginal title [8].

- Another failure of the Provincial and Federal governments is the failure to recognize the rights that the Wet’suwet’en hold under UNDRIP. Canada is a signatory to this declaration and the BC government has more recently assented to Bill C-41. These two legal documents should make BC’s laws adhere to the rights of indigenous peoples. However, as we are seeing in the case of the Coastal GasLink pipeline, BC’s laws are contradicting many of the articles contained within UNDRIP and its own SBC 2019 c 44[12].

Assessment

High Power: TransCanada Energy Corporation – Coastal GasLink

TC Energy is an affected stakeholder that holds a significant amount of power in this issue. TC Energy does hold some legal power in this issue because they have been granted legal authority from the provincial government to have access to the land on which the pipeline is being constructed on[38]. Additionally, they have the management rights to the land. They also have the ability to manage the area in which the pipeline will reside. TC Energy holds some key strands from the bundle of rights.

High Power: BC Provincial government and the Canadian Federal government

The provincial government of BC is a major stakeholder in this issue and holds the majority of the legal power. The BC government holds legal authority over the land because the Wet’suwet’en have not established aboriginal title over their traditional territories. Under the Canadian Constitution Act of 1982, aboriginal title is protected but it is only protected if its extent has been determined, which is not the case for the Wet’suwet’en[23]. In this case, the land is considered to be crown lands. The provincial government holds all of the strands of the bundle of rights which include access, withdrawal, management, exclusion, alienation, bequeathal, and extinguishability rights on crown land[39].

Low Power: Wet’suwet’en Nation

The Wet’suwet’en Nation are affected stakeholders that hold low legal power in this issue. Under the current situation in BC the Wet’suwet’en along with the majority of First Nations do not have control over their traditional territory legally. Their traditional territory is defined as crown land as it stands today, which is held and controlled by the government. The Wet’suwet’en do not have control over their territory because they have not established aboriginal title, according to Canadian law[23]. With recognized aboriginal title the Wet’suwet’en would have access to many of the strands of the bundle of rights, whereas in the current situation the Wet’suwet’en almost have no strands of the bundle of rights.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (2019). "2018 Economic Report Series LEVERAGING OPPORTUNITIES: DIVERSIFYING CANADA'S OIL AND NATURAL GAS MARKETS" (PDF). line feed character in

|title=at position 54 (help) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 TransCanada PipeLines (2020). "Coastal GasLink". TC Energy. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 TransCanada Pipelines Ltd. (2020). "Indigenous Relations". Coastal GasLink. Retrieved 11/4/2020. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 Stuck, W (2020, February 11). "Beyond Bloodlines: How the Wet'suwet'en hereditary system at the heart of the Coastal GasLink conflict works". The Globe and Mail. line feed character in

|title=at position 51 (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 Montenegro, YA (March 6, 2020). "Wet'suwet'en Action Timeline". The Leveller. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ↑ "Coastal GasLink Overview". TC Energy. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Our Mission". Office of the Wet'suwet'en. 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 Borrows, J (1999). "Sovereignty's Alchemy, An Analysis of Delgamukw v British Columbia". Osgoode Hall L.J.: 537–596.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Gunn, K (2020, February 13). "The Wet'suwet'en, Aboriginal Title and the Rule of Law: An Explainer". First People's Law. line feed character in

|title=at position 43 (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Wilson-Raybould, J (2020, January 24). "Who speaks for the Wet'suwet'en people? Making sense of the Coastal GasLink conflict". line feed character in

|title=at position 40 (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ "Indian Act and Elected Cheif and Band Council System". Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. 2015, June 25. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 UN General Assembly. (2007). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples(A/RES/61/295). New York.

- ↑ 41st Parliament, 4th session (2019). "Bill C-41: Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act".

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Natural Resources Canada (2020-03-30). "Natural Gas Facts". Canada.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (2019). "Canadian Economic Contribution". CAPP.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Revised Statutes of Canada (1985). "Expropriation Act". Retrieved 2020-04-09.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Lindsay, Bethany (Dec 31, 2019). "B.C. Supreme Court grants injunction against Wet'suwet'en protesters in pipeline standoff".

- ↑ Maurer, Matt (Feb 25, 2014). "The Civil Injunction Cheat Sheet". Slaw.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 19.6 19.7 The Canadian Press (February 24, 2020). "Timeline of the Wet'suwet'en solidarity protests and the dispute that sparked them". Global News. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ↑ Ridsdale, John (2020). "Wet'suwet'en Hereditary Chiefs Reject the BC Supreme Court Decision to Criminalize Wet'suwet'en Law". Unist'ot'en.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Johnson, Rhiannon (Feb 10, 2020). "RCMP arrests in Wet'suwet'en territory spark protests nationwide". CBC News.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 The Office of the Wet’suwet’en (2013). "Wet'suwet'en Title and Rights" (PDF).

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 "Constitution Act 1982". Government of Canada. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ↑ Abedi, Maham (Feb 7, 2020). "Wet'suwet'en protests and arrests: Here's a look at what's happening now". Global News.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 BC Treaty Commision (2020). "Aboriginal Rights".

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 HONOURABLE SCOTT FRASER MINISTER OF INDIGENOUS RELATIONS AND RECONCILIATION (2019). "BILL 41 – 2019 DECLARATION ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES ACT".

- ↑ Wickham, Jennifer. "Wet'suwet'en Hereditary Chiefs Call For UN Intervention".

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Cox, Sarah (Jan 9, 2020). "'What cost are human rights worth?' UN calls for immediate RCMP withdrawal in Wet'suwet'en standoff". The Narwal.

- ↑ British Columbia (2020). "First Nations Coastal Gaslink Agreements". www.gov.bc.ca.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Province of British Columbia, Minister of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation (Nov 26, 2014). "Coastal Gaslink Pipeline Project Natural Gas Pipeline Benefits Agreement" (PDF).

- ↑ Kitselas First Nation (2019). "Annual Report 2018/19" (PDF). Kitselas.com.

- ↑ The Province of British Columbia, Skin Tyee First Nation (Dec 1 2014). "Coastal Gaslink Pipeline Project Natural Gas Pipeline Benefits Agreement" (PDF). Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 33.0 33.1 Wallace, Aidan (February 22, 2020). "Pipeline Protests: Timeline of how we got here". Toronto Sun. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ↑ Little, Simon; Boynton (Feb 19, 2020). "Anti-pipeline protesters block traffic in major East Vancouver intersections". Global News.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 McIntosh, Emma. "The draft deal between the Wet'suwet'en and the government explained". National Observer. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ↑ "Hundreds rally in Metro Vancouver and Victoria in solidarity with Wet'suwet'en". CBC News. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ↑ Kennedy, Brendan. "Via Rail and CN suspend service amid Wet'suwet'en blockades". The Star. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ↑ "Land Use - Oil & Gas". Government of B.C. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ↑ "Crown Land & Water Use". Government of B.C. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

| This conservation resource was created by Course:CONS370. It has been viewed over {{#googleanalyticsmetrics: metric=pageviews|page=Course:CONS370/Projects/The Wet’suwet’en Nation, British Columbia, Canada and the Coastal GasLink pipeline: history, jurisdictional issues, positions, alliances and potential outcomes|startDate=2006-01-01|endDate=2020-08-21}} times.It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |