Course:CONS200/2023WT1/The Recovery of The Louisiana Black Bear and The Wetlands Reserve Program

Introduction

The Louisiana Black Bear (Ursus americanus luteolus) was designated as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act in 1992[1]. This classification came as a response to a significant decline in their population, primarily attributed to overexploitation and habitat loss during the 19th and early 20th centuries[1]. Overexploitation resulted from the extensive hunting of these bears, while habitat loss was primarily a consequence of deforestation for timber harvesting and land clearance for agriculture[1]. The Louisiana black bear plays a crucial role in the ecosystem as both seed dispersers and regulators of insect populations[2]. Their primary habitat consists of large, contiguous areas of hardwood forests, which were historically prevalent in the Mississippi River region[2]. However, human development has severely disrupted these areas, leading to a substantial reduction in suitable habitat for black bears[2]. By 1950, the black bear population had dwindled to just 80 to 120 individuals[2]. Black bears, like other big mammalian species, have slow life history traits[3]. They have relatively small litter sizes, low density, longer time for age at first reproduction, longer interbirth intervals, and larger home-range sizes compared to animals with fast life history traits[3]. These factors contribute to lower detectability and, thus, difficulty in surveying or monitoring the population. Today, ongoing restoration efforts, such as the Wetlands Reserve Program initiated by the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), have contributed to a resurgence in their population, which now ranges from 500-750 bears[4]. Controversially, they were removed from the "threatened" species list in 2016 due to the increase in population size[5]. This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the Louisiana black bear and the Wetlands Reserve Program. It will delve into the historical factors responsible for the decline in the black bear population and the ongoing initiatives to restore the ecosystem and rejuvenate the black bear population.

Distribution and Critical Habitat of Louisiana Black Bear

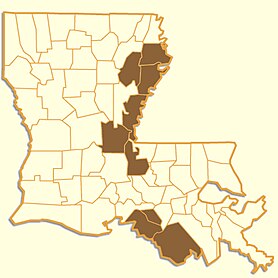

The Louisiana black bears are initially from eastern Texas and dispersed throughout Louisiana and southwest Mississippi.[6]. They rely heavily on wetlands as their habitat. In the early 20th century, their presence dwindled in Texas, and currently, they are only found within the confines of Louisiana[7], excluding a small area in Mississippi where a population also resides[8].

Conservation efforts have been initiated after the classification of the species as threatened. Black bears require specific habitats encompassing food sources, water, cover, and denning sites, ideally arranged across extensive, remote blocks of land[7]. The significance of remoteness as a habitat factor is crucial for black bears, as tracks and roads diminish remoteness and signify human disturbances[7]. A key consideration in habitat preservation is the quality of cover for bedding and denning. As forest sizes decrease and fragmentation occurs due to human activities, the quality of cover for black bears diminishes[7]. Hence, identifying critical habitat becomes imperative for effectively conserving the black bear population.

Unfortunately, the federal listing of Louisiana black bear was originally made without considering aspects of critical habitat[7]. Subsequently, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service designed critical habitat areas for the Louisiana black bears to restore the degraded habitats.[9]. The historical areas once inhabited by black bears were characterized by bottomland hardwood forests featuring diverse trees with escape cover[9]. Consequently, the designated critical habitat areas for conservation are bottomland hardwood forests, specifically those near river basins[10], such as the Atchafalaya River Basin[4][8][9].

Ecological role of Louisiana Black Bear

The Louisiana black bear is an umbrella species, playing a pivotal role as a large mammalian predator within its ecosystem[11]. An umbrella species shares similar ecological niches and requirements with other species in the same habitat[12]. Thus, conserving the black bear inadvertently supports numerous other species inhabiting the region[11]. The influence of the Louisiana black bear extends beyond wildlife conservation to positively affect humans. They are unique to other black bear species due to their longer, narrower, and flat skulls with proportionately larger molar teeth[6]. With an omnivorous diet that includes berries and roots alongside meats, they contribute to supporting pollinators[11][13].

Furthermore, as a founder species, their population growth and habitat range expansion can lead to the classification of distinct groups or subspecies over time[11]. The black bear's habitat, the bottomland hardwood forest, represents an ecosystem characterized by diverse and abundant vegetation, offering potential environmental benefits[11]. This habitat in Louisiana includes wetlands and river deltas that act as buffers against significant catastrophes. Therefore, safeguarding the Louisiana black bear's habitat not only preserves the species but also holds the potential to provide essential benefits to the human population in the area[11].

As apex predators, Black bears hold a significant ecological role as large carnivorous and omnivorous species within their ecosystem. They serve as top-down regulators, influencing the balance of species below them in the food chain[14]. The hibernation and activity patterns of black bears, particularly during the summer and fall seasons, exert control over mesocarnivore species like coyotes and bobcats[14]. Consequently, alterations in black bear populations can trigger trophic cascades, defined as changes at one trophic level that generate repercussions at multiple trophic levels[14]. When black bear populations decrease, it disrupts the intricate web of species interactions. The resulting increase in mesocarnivore species leads to a decline in smaller prey species. This disturbance creates an imbalance in the ecosystem's species dynamics, potentially causing ripple effects throughout the trophic levels. Thus, preserving the population of black bears is crucial for maintaining stability and harmony in the intricate web of ecological relationships within their habitat.

The Problem

The population of Louisiana black bear is very small between he habitats it resides. They have been protected under the endangered species act in 1992 until 2016, when they were removed as their critical habitat had been deemed to be restored[5][15], and their population had risen. Since then, its been controversial whether the current conservation for this species is enough.

Bear hunting season in Louisiana is becoming required as of this year (2023), which will normalize the hunt of Louisiana Black bears within the state[15]. This is a major fault in policy making for the conservation conservation of the species, since there are only approximately 500-750 bears within Louisiana[4]. They are not properly recovered from being threatened, so making hunting legal may cause a large shock to the population, and cause it to decline once more[15].

Furthermore, there is controversy in the effectiveness of the current conservation of the bears[15], and if their critical habitat is properly being resorted. Due to their range being heavily fragmeneted, this is further harming efforts for populations to be resorted[8].

For proper understanding of the problem, we must break down the individual causes are leading to these situations.

What is Causing it?

The main causes that has led to population decline in Louisiana black bears has been human disturbance[1][8]. Unfortunately, as we continue to take from the land, and alter our climates, species populations are declining across the world heavily. This is documented by the Living Planet Index, which was recorded a 68% in species populations globally, majorly due to overexploitation by humans[16]. As populations decline and their habitat becomes more sparse, reproduction becomes a major issue in the preservation of threatened species. As the land has become more and more impacted by humans, so has the population of black bears, their fitness, and success in the wild.

Destruction of Habitat

From the 18th century until this day, the loss of wetland area in Louisiana and Mississippi creates a necessity for sustainable management and conservation within the areas. The historical habitat of the Louisiana black bear spread throughout all of Louisiana, and into many of the states surrounding it[6][8]. Throughout many years of agriculture, forestry, and climate impacts, the critical habitat for Louisiana black bears has decreased dramatically[7]. From the 18th century to late 19th century, 9.7 million hectares of critical habitat for Louisiana black bear was reduced to 2 million hectares for agriculture in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley, and forest harvesting throughout the states[2]. This has restricted the species' habitat to very separated areas throughout Louisiana and Mississippi, which are sparsely connected[8]. Since then, the hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005 have also contributed heavily to habitat loss, resulting in the loss of 56000 hectares of wetland[17] on the coasts.

Human-Bear Conflicts

Another of the major causes influencing the population of Louisiana black bears has been the interactions between humans and them. A main factor that has contributed the decline in their population from this cause was the hunting of Louisiana Black Bears from the 19th to 20th century[1]. In 1992, when they were listed as a threatened species[1], the hunting of Louisiana Black bears was made illegal. However, poaching of the species is still a major concern, and is still a threat to individuals in the wild to this day. In 2023, we are experiencing the risk of the state of Louisiana re-opening bear hunting season, which could result in another population decline due to the fragility of the species' population[15].

Car collisions with bears is also very common, especially in Louisiana, which was the leading cause of mortality to Louisiana black bears from 1992-2014, resulting in the death of over 246 bears [8]. On top of this, human interactions with bears, such as feeding on garbage, encounters on trail, etc., which can cause altered behaviors, such as dependency or aggression in some bears, and lead to bear-nuisances and possibly attacks[1]. In response, the BBCC (Black Bear Conservation Committee) has commenced a bear conflict management team to reduce the amount of human-bear conflicts with the goal to reestablish and bring together black bear habitat components that are essential for their long term protection[18].

Reduced Population & Reproduction

Louisiana black bear are dependent on their winter storages to survive[8]. Before the winters, they should be socking up on as much fat as possible. Although they do not truly hibernate, and instead undergo a dormancy period dubbed 'carnivoran lethargy'[8], it is still crucial to their life cycle. Female bears will develop delay blastocyst formation as a result of low nutrient supply in the winter to protect the embryo during dormancy[8]. If the fat supplies are not great enough, the bear will not produce viable offspring[8]. Additionally, Louisiana black bears only den during the winter, and in heavy cover areas or tree cavities.

These are necessities for the Louisiana black bear to be able to reproduce properly. Due to habitat fragmentation and population loss, this is leading to struggles in reproduction of the population, as they aren't able to collect enough fat storages for the winter, or find proper denning habitat[1][8].

Remedial Actions

Looking back, the Louisiana black bear population has suffered from hunting in the 19th and early 20th centuries, as well as widespread deforestation from manufacturing of wood products and clearing lands for agricultural practices, which has since, significantly reduced their population size[1]. However, the Louisiana Black Bear was listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1992[1]. More specifically, once an animal is listed as endangered, it receives special protection from the federal government[1]. Furthermore, in 1995 the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service developed a recovery plan for the bears that gave their population and habitats full protection[1]. As a result, not only has this stopped the loss of forested lands in the Lower Mississippi River Alluvial River Valley but it has also resulted in a significant increase in habitats being protected[1]. As part of restoring the bear habitat, 480,836 acres have been permanently protected[19]. Louisiana, Texas, and Mississippi are all having public workshops and black bear management plans to guide restoration[19]. More than 25 research studies have been conducted on habitat requirements, taxonomy, and genetics which have led to increased knowledge about the bears' behaviors, population attributes, home ranges, and population growth rates[19]. The Louisiana Department of Wildlife & Fisheries (LDWF) have been coordinating with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) to track the bears occurrences and captures to manage and better understand the subpopulations[19].

Along the same lines, it is evident that human-related mortality continues to be a primary threat to the recovery of the Louisiana Black Bears[20]. That being said, although hunting was suspended in 1988, illegal killing as well as vehicle collisions have been a leading cause in confirmed deaths[20]. However, a milestone was reached in 1995 when a recovery plan made by the Black Bear Conservation Committee and the USFWS and approved[20]. The plan consisted of three layers of criteria 1. At least 2 viable subpopulations, 1 each in the Tensas and Atchafalaya River basins 2. Establishment of immigration and emigration corridors between the 2 subpopulations, and 3. Protection of the habitat and interconnecting corridors that support each of the 2 viable subpopulations used as justification for delisting[20]. Following these criteria the plan also includes four actions that must take place to meet these criteria 1. Restore and protect bear habitat, 2. Develop and implement information and education programs, 3. Protect and manage bear populations, and[20] 4. Conduct research on population viability and bear biology[21].

In order to keep track of the success of these remedial actions, the marked and recaptured black bears are tagged for hair samples[20]. The use of DNA sampling has been successful in estimating bear populations in Louisiana as the DNA cannot be altered and is unique to each individual bear[20]. Additionally, there are 118 hair sampling sites that use 4-point, 15.5-gauge barbed wire that is tightly stretched around 3-5 trees of which the bears will naturally dispense hair samples into[20]. The bears are baited in with approximately 100g of sweet baked goods which are suspended above the ground in the middle of the hair site[20].

Wetlands Reserve Program

The Wetlands Reserve Program (WRP) is a voluntary conservation held by the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), providing landowners with financial incentives for restoring the wetlands and retiring from agricultural production[22]. Depending on the easement secured, the government will pay all or partially, and landowners will receive a subsequent payment for their easements done[22]. Most of the restorations are done in the Mississippi River Alluvial Valley, and by 2003, nearly 600,000 ha had been involved[22]. The goal of WRP is to protect and enhance suitable habitats for wildlife by restoring the vegetation in the bottomland hardwood forests[22]. From the 1780s to the 1980s many states experienced an extremely damaging loss in wetlands due to the conversion of land from native habitats to agricultural land[23]. Moreover, the damages consisted of excessive drainage and alteration of these wetlands which led to the creation of the Wetland Reserve Program[23]. Specifically, in 1990 the Wetlands Reserve Program was authorized by Congress as a part of the Food Security Act[23]. Once the WRP was put in place, national focus had shifted towards restoring Wetlands and preserving those that still exist[23]. Furthermore, the lands that are protected by the WRP provide habitat for wildlife, decrease flood damages, improve water quality, enhance traditional cultural opportunities for American Indians, help the recovery of endangered and threatened species, and allow farmers and others to maintain ownership of lands that are ready for wetland restoration[23].

The Natural Resources Conservation Service helps fund the WRP by providing financial assistance in the form of easement payments and restoration cost-share assistance to ensure the long-term survival of wetland restoration[23]. Conversely, many animals have been negatively impacted by the loss of wetlands, one of those being the Louisiana black bear. Once a largely populated species in the Mississippi River Delta, the population was severely impacted by habitat loss[9]. The Louisiana black bear requires large and dense areas of bottomland hardwood forest which were once common to the Mississippi River Delta, however large areas of forest began to disappear in the late 18th century due to agricultural practices and accelerated land clearing associated with record high prices for soybeans[9]. Black bears are important in these ecosystems because of their effect on populations of insects and fruits which helps keep the biodiversity levels stable[9]. Of what used to be 24 million acres of forest in the Lower Mississippi Alluvial Valley, less than 5 million acres remained in 1980[9]. The WRP has since helped restore the habitats for bears and population numbers are now estimated at 500 to 700[9]. The population seems to be growing[9][4], and are no longer listed as threatened[5], but are still at risk from human activity. Of the 50 regions in the Mississippi River Alluvial Valley, 23 have successfully met their core goals, while 27 regions are still awaiting evaluation for their success[22]. Furthermore, there is limited information available regarding local-scale restoration efforts, and the most recently established micro and macro-topographic wetlands exhibit insufficient density and diversity of emergent and submergent plant species[22]. There is insufficient data for most of the wildlife due to the lack of monitoring done within the regions of WRP[22]. More time is needed to collect enough data to measure the success of WRP[22].

Future Solutions

To further keep the Louisiana Black Bear populations trending in the right direction, private and public alliances are key for future recovery[18]. Incorporating management for wildlife populations play an important role on both public and private land[24].

Black bears do not move from high-density areas to Mississippi areas where suitable habitat exists. Therefore, translocation is necessary[25].

In order to successfully manage the relocation or translocation, it is important to choose the reference condition. The reference condition is the biotic and abiotic conditions to which we wish to restore our ecosystem[26]. The reference conditions form a base of comparison with contemporary ecosystems and allow us to anticipate population augmentation. Black bears are habitat-sensitive species, therefore we need to measure the suitable habitat referring to reference conditions that they once occupied before. Often times, the habitats provided for black bears are not suitable and large enough to adequately protect the black bears which would result in a difficult recovery[24]. Furthermore, recognizing and analyzing the reference conditions, allows the managers to understand the factors that reduced the black bear populations[27]. This is advantageous for future applications to eliminate the threats prior to the relocation.

Once there is a successful relocation of the black bears, the goal of these habitats is to impose two different subpopulations and restoring the habitat with interconnected corridors between the habitat fragments[18]. Possible solutions for suitable habitats include national parks and national forests[24]. With the increasing impacts of climate change, the black bear's habitat is left vulnerable to the rising sea levels[19]. This is an important considering black bear's habitats are in areas of low elevation near the coast[19]. Currently there is a lack of observed black bear data that has been found in local areas[24]. Collecting more local data would be beneficial since it would bring adaptive management framework along the management guidelines and revising metrics that are network-related[24]. The BBCC (Black Bear Conservation Committee) has major goals for long term protection which include the effective use of resources, focusing efforts on a diverse user group, and educating the public about the black bears[18].

Conclusion

Many impacts to the critical habitat and population of Louisiana black bear has influenced why they have been threatened species in the past[1], and could become one again[15]. Habitat loss, and human-bear conflicts have been the main causes leading to this[1], which have resulted in the species having difficulty recovering. They are still in need of conservation, as they are still exposed to many anthropogenic factors that could future declines in their small populations in Louisiana and Mississippi.

Although Louisiana black bear populations have recovered and have had an increase in population in the last 20 years or so[1], it is crucial that we still manage these populations so that they do not be listed as endangered again in the near future. While the recovery to remove it from the endangered list in 2016 was successful[1], there are new threats such as climate change and conflicts with humans emerging. There are many efforts mentioned to help with conservation such as the Black Bear Conservation Committee, the Wetlands Reserve Program, and the cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. However, due to the lack of monitoring efforts, data are insufficient enough to evaluate the efficiency or success of WRP. Furthermore, removing the Louisiana black bears from the endangered species list solely due to their increased population emphasizes the short-term interests of decision-makers. The removal of black bears from the list was due to economic impact and bureaucratic process costs[28]. More studies had to be done before removing them from the list with uncertainty about whether the black bears can self-sustain without protection. Acknowledging the significance of long-term management action is required for further restoration of wetland habitats and wildlife species.

Overall, there have been many actions put in place to save the Louisiana Black Bears whether that was by the Wetlands Reserve Program or other Black Bear conservation programs. Each of these programs have their own policies which all relate on some level of agreement, however, there has been only a small amount of success in bringing back such a large species. That being said, as these programs and committees continue to expand and develop more concrete ways of establishing new habitats and resources for these bears, the world will begin to see a sudden re-emergence of this population.

Reference

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 "Louisiana Black Bear". Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. Retrieved 10/30/2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Lemoine, Kristen; Pitre, John (09/09/2010). "NRCS Wetlands Reserve Program Aids in the Recovery of Louisiana Black Bear Habitat". USDA. Retrieved 10/30/2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 Paemelaere, Evi; Dobson, F. Stephen (July 2011). "Fast and slow life histories of carnivores". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 89: pp.692-704.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Bear Conservation (February 20, 2021). "Louisiana black bear". Bear Conservation.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Louisiana Black Bear". Bear Conservation. 20, February 2021. Retrieved 08, December 2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Louisiana Black Bear". U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. 11/02/2023. Retrieved 11/02/2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 "Louisiana black bear" (PDF). Texas A&M Forest Servie. 08, December 2023. [tfsweb.tamu.edu Archived] Check

|archive-url=value (help) from the original on|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help). Retrieved 08, December 2023. Check date values in:|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries (January 2015). "Louisiana Black Bear Management Plan" (PDF). Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 "ETWP; Proposed Designation of Critical Habitat for the Louisiana Black Bear" (PDF). U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. December 2, 1993. Retrieved 11/02/2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name ":4" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ "Designation of Critical Habitat for the Louisiana Black Bear (Ursus americanus luteolus): Proposed rule" (PDF). U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. 05/06/2008. Retrieved 11/02/2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Mathias, Lauren (05/13/2020). "Designing against habitat loss: Facilitating movement of the Louisiana black bear". Illinois Library. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Umbrella Species". Nature Conservancy Canada. 12/10/2023. Retrieved 12/10/2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ "Black Bear". The National Wildlife Federation. 12/10/2023. Retrieved 12/10/2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Moll, Remington J.; Jackson, Patrick J.; Wakeling, Brian F.; Lackey, Carl W.; Beckmann, Jon P.; Millspaugh, Joshua J.; Montgomery, Robert A. (May 2021). "An apex carnivore's life history mediates a predator cascade". Oecologia. 196: pp.223-234.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 Atchafalaya Basinkeeper (2022). "The Louisiana Black Bear Litigation". Atchafalaya Basinkeeper. Retrieved December 6th, 2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ WWF (2020) Living Planet Report 2020 - Bending the curve of biodiversity loss. Almond, R.E.A., Grooten M. and Petersen, T. (Eds). WWF, Gland, Switzerland.

- ↑ Murrow, J. L. (2012). "Effects of hurricanes Katrina and Rita on Louisiana black bear habitat". Ursus. 23(2): 192–205.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Bowker, Bob; Jacobson, Theresa (September 27, 1995). "Recovery Plan: Louisiana Black Bears" (PDF). pp. 1–59. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Removal of the Louisiana Black Bear From the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Removal of Similarity of Appearance Protections for the American Black Bear" (PDF). U.S Fish & Wildlife Service. March 11, 2016. pp. 1–49. Retrieved November 2, 2023. line feed character in

|title=at position 73 (help) - ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 20.7 20.8 Troxler, Jesse (2013). "Population Demographics and Genetic Structure of Black Bears in Coastal Louisiana". Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange.

- ↑ "Louisiana Black Bear". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2023. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 22.6 22.7 King, Sammy L.; Twedt, Daniel J.; Wilson, Randy R. (December 2010). "The Role of the Wetland Reserve Program in Conservation Efforts in the Mississippi River Alluvial Valley". Wildlife Society Bulletin. 34: pp.914-920.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 "Natural Resources Conservation Service" (PDF). Wetland Reserve Program. January 2009. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 Morzillo, Anita; Ferrari, Joseph; Liu, Jianguo (September 25, 2010). "An integration of habitat evaluation, individual based modeling, and graph theory for a potential black bear population recovery in southeastern Texas, USA". pp. 69–81. doi:10.1007/s10980-010-9536-4. Retrieved December 12, 2023. line feed character in

|title=at position 55 (help) - ↑ Bowman, Jacob L.; Leopold, Bruce D.; Vilella, Vilella; Francisco J., Gill (2004). A SPATIALLY EXPLICIT MODEL, DERIVED FROM DEMOGRAPHIC VARIABLES, TO PREDICT ATTITUDES TOWARD BLACK BEAR RESTORATION. The Journal of Wildlife Management: Duane A. pp. pp. 224. ISSN 0022-541X.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- ↑ Fule, Peter Z.; Covington, W. Wallace; Moore, Margaret M. (1997). "Determining Reference Conditions for Ecosystem Management of Southwestern Ponderosa Pine Forests". Ecological Applications. 7: pp.895-908.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- ↑ Hess, Silvia; Alve, Elisabeth; Andersen, Thorbjørn J.; Joranger, Tore (April 2020). "Defining ecological reference conditions in naturally stressed environments – How difficult is it?". Marine Environmental Research. 156.

- ↑ Gordon, Robert. ""Whatever the Cost" of the Endangered Species Act, It's Huge" (PDF). Competitive Enterprise Institute.

| This conservation resource was created by Course:CONS200. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |