Course:CONS200/2021/Old-growth logging in British Columbia: current situation, issues, and key debates

Old-growth forests are defined as greatly-aged forests that have faced no significant disruptions over its lifetime[1]. They are proven to make unique contributions to ecology and biodiversity[1]. Old-growth logging originated from the expansion of British Columbia’s forestry industry[2]. Economic drivers and demand for lumber products motivates old-growth logging[3]. In recent decades, there have been increased calls for action and initiatives to oppose old-growth logging[4].

Introduction, History, and Current Overview

Forestry has been an integral part of British Columbia’s history, culture, and economy since the province’s inception in 1858[5]. Forestry was once British Columbia’s main economic driver[6]. Though no longer the main driver, it remains an important part of the economy[7]. In 2020, the logging and forestry sector was responsible for $11.5 billion of B.C.’s total exports[6]. The forestry sector also accounts for thousands of jobs for the residents of B.C., and generates revenue for the federal and provincial governments through stumpage fees and taxes[6]. It is an integral part of the culture and livelihood of the province.

Increasing Scales of Logging

Globally, forests cover roughly 31% of the earth’s land surface[8]. Human populations and economic activities have increased exponentially since the industrial age, leading to increasing anthropogenic abilities to manipulate the environment[8]. British Columbia’s total area is almost 95 million hectares; of those 95 million hectares, 57 million hectares are forest based[6]. 23% of the forests in B.C. are considered old-growth[6]. Based on data from 2014-2018, about 200 000 hectares of forested land are harvested every year in British Columbia, equalling approximately 1% of the harvesting land base[7]. Of this 1% annual harvest, 27% comes from old-growth forests[7].

Prior to the 20th century, B.C.’s old-growth forests were extensive[6]. Until the early 1900s, logging in B.C. was limited by access. There were few roads into the forests, so logging took place on the outskirts of forests or in places where timber could be moved by water, meaning that most of the forests were ignored[6]. In the mid-20th century, the scope and scale of harvesting increased markedly; the public became aware that the province’s timber supply was not unlimited and was being exhausted[6].

Public Awareness of Logging Practices

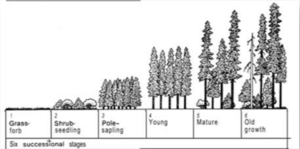

Public awareness of resources resulted in a policy of “sustained yield”, turning natural forests into managed forests, mainly by clearcutting[6]. However, the problem with sustained yield and old-growth forests is that while trees are a renewable resource, old-growth forests are not a renewable resource[9]. B.C.’s old-growth forests range in age from 200 to 2000 years old[9]; the farmed trees in these managed forests are cut down every 60-100 years[6], meaning they will never become old-growth. It also leads to a high variability in secondary growth across the province[6]. While some re-planted farmed trees will be loggable in a few years, other areas of the province will take several decades for its secondary growth trees to be loggable again[6].

Following global trends in the 1980s, the public became more aware of the importance of the ecological values that trees and forests provide[6]. As a result, more parks and conservation areas were created, reducing the amount of forest available for conversion to managed forests[6]. It also led to the imposition of new restraints on forestry practices, based on waterways, wildlife, and biological diversity, amongst others[6].

Until the mid 1990s, most forest harvesting in British Columbia was done by clearcutting[6], which is the removal of all trees from an area of one hectare or more in a single operation[6]. This is because it is the most efficient and least expensive method[6]. As the environment and forests became more important to the public, other methods of harvesting trees were developed: clear cutting with reserves (clear cutting that retains either individual trees or small pockets of trees, for the purpose of providing wildlife habitat, nesting areas, or visual quality[6]), retention cutting (cutting the top part of trees only, to retain structural integrity in forests[10]), and other cutting methods. By 2016, clearcutting only accounted for 11% of the forest harvesting done in British Columbia[6].

Current Logging Circumstances

The logging of old-growth forests in British Columbia has remained a point of contention between the government, forestry companies, and the public across many decades. In 1993, the largest act of civil disobedience in Canadian history to that point occurred over the logging of old-growth forests in Clayoquot Sound (pronounced Klak’wat) on Vancouver Island’s west coast[11]. This protest led to the arrests of over 800 people standing in the way of the logging route[11]. The logging of Clayoquot Sound’s old-growth forests was led by MacMillan Bloedel, a major forestry company founded in British Columbia in 1909[12].

The logging of old-growth forests continues in British Columbia today. The most recent logging of old-growth forests in British Columbia is in Fairy Creek, a forested watershed tributary to the San Juan River located in the southwest of Vancouver Island[13]. The Fairy Creek watershed is a part of Tree Farm Licence 46, a 59,000 hectare timber harvesting area that is owned by Teal Jones[14]. John Horgan’s NDP government promised in early 2020 to put an immediate halt to the logging of British Columbia’s rarest forests, including Fairy Creek, but as of late 2021 have yet to do so[15]. Public pressure to stop all old-growth logging in British Columbia has increased in recent years, but definitive actions regarding these forests have yet to be seen[15].

Driving Factors for Old-Growth Logging in British Columbia

Commercial Forestry and Logging

Beginning in the 1820s, commercial forestry and logging has been an active industry in British Columbia[2]. The industry and its related operations have served and continue to serve as an economic pillar for the province[7]. Companies engaged in commercial logging seek returns for their operational investments[16]. These investments are returned through the sale of harvested timber that has been processed to contribute to architectural or structural applications, and is used in the production of specialty products[7]. Logging technology has progressed to accommodate for the efficient harvesting and processing of timber, its workforce, and its products[2]. The advancement of forestry and logging technology has allowed for the widespread accelerated harvesting of timber[2]. Following the long-term industrial logging of forests in British Columbia, the depletion of usable forests has caused logging operations to continually advance into unlogged land[2]. This has led commercial logging to come into more contact with old-growth forests that can be harvested to sustain its industry[9].

Old-Growth Timber Availability

Old-growth forests are a resource with shrinking availability to logging within British Columbia[9]. 42% of land in British Columbia is available for logging[17], and 12.6% of this 42% is old-growth forest in which logging is permitted[18]. According to data from 2012, 74% of British Columbia’s original old-growth forests have been logged since commercial logging in British Columbia first began[9]. Only 26% of British Columbia’s original old-growth forests remain, 8% of which are under protection from logging[9].

Old-growth timber is a scarce resource compared to second-growth timber, and is much more valuable to the commercial logging industry than second-growth timber[3]. The inherent properties of old-growth forests and its timber mark it as a particularly valuable product in British Columbia’s forestry industry[7]. Old-growth timber is of high economic value because of their significantly greater timber volume per hectare compared to second-growth timber[9]. Old-growth timber is known for its comparatively stronger wood and denser wood grain growth; in the process of creating wood products, these features make the timber easier to create products with because the timber’s properties prevent it from cracking[3]. The scarcity of old-growth timber’s availability in tandem with its inherent value for different purposes drives the sustained logging of old-growth forests[9].

Environmental Impacts of Old-Growth Logging

The old-growth forests found in British Columbia support complex ecosystems unique to trees that are hundreds of years old[1]. Many endangered and threatened species have become heavily dependent on these ecosystems for their survival, making these areas very ecologically valuable[1]. Old-growth forests in British Columbia have developed for hundreds of years and are disproportionately more sensitive to disturbances compared to young forests[19]. Following deforestation, much more time is needed for them to recover their original states[19]. Due to this fragility, logging has had significant environmental impacts on old-growth ecosystems. Notable environmental impacts that logging has on old-growth forests are habitat fragmentation, loss of connectivity, and the disruption of carbon sequestration[20].

Habitat Fragmentation

The process of fragmentation refers to the act of splitting a once continuous habitat into smaller, isolated patches, which logging and associated activities cause by creating logging roads and harvesting trees[21]. The results of reducing old-growth habitat sizes are reflected by observing the effects that it has had on bryophytes, a group of mosses. In situations where habitats have been fragmented into areas smaller than 3.5 hectares, bryophyte populations were less successful than populations that inhabited larger fragments or unfragmented old-growth habitats[22]. The building of logging roads has been especially detrimental to mountain caribou populations as it has further exposed them to human activities, and has made them increasingly vulnerable to predators[19].

Loss of Connectivity

Loss of connectivity threatens the preservation of biodiversity and the survival of species that have low vagility such as chickadees and nuthatches[20]. Logging in old-growth forests has also significantly impacted nearby watersheds and aquatic ecosystems[19]. The removal of mature trees and other vegetation compromises the surrounding soil’s stability, increasing soil susceptibility to erosion[19]. Streams running through logged areas have a higher likelihood of widening due to bank erosion[19]. In logged areas, increased levels of sediment deposition are observed[19]. Stream water temperatures increase due to the loss of canopy cover surrounding them, which can stress aquatic organisms that inhabit them[23].

Disruption of Carbon Sequestration

The disruption of carbon sequestration is an additional consequence of logging[24]. Old-growth forests are responsible for absorbing substantial amounts of atmospheric carbon dioxide[24]. When logging takes place, the amount of carbon that can be absorbed and stored in the future is reduced[24]. This will contribute to the increasing levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, which is a cause for global concern regarding climate change when compounded with other unrelated sources that contribute to greenhouse gas levels[19]. The severity of these repercussions is dependent on logging strategies, with clear cutting and small isolated fragmented habitats having the most significant negative environmental impacts, and conversely with selective harvesting and preserving large areas fragmented habitat having lesser impacts[22].

The Future of Old-Growth Logging in British Columbia

Future Policies and Implementations

The future of old-growth logging is dependent on future policies and approaches to logging that are implemented. Current policies on old-growth logging are advised to address current ecological challenges and implement commitments to supporting natural ecosystems[4]. The total area of old-growth forest in British Columbia has significantly declined in the past 20 years, from 25.3 million hectares in 1998 to 13.2 million hectares in 2021, and it is predicted to continue to fall[4]. The future of old-growth forests depends on the type, duration and magnitude of future disturbances. It is suggested that initiating forest management strategies is an effective strategy for the provincial government to manage future forest wellbeing in British Columbia[4]. Old-growth forests are identified as high-productivity areas whose protection is called for by international conventions such as the Convention on Biological Diversity[4]. Analyses suggest that government designations for land conservation are an effective approach to protecting old-growth forests[4]. Protected area targets are highlighted as a realistic implementation that can protect an additional 307 000 hectares of previously-unprotected old-growth forests[4].

Governmental and Local Conservation Collaboration

Collaboration with local stakeholders in old-growth protection has also been adopted. The British Columbian provincial government is increasing its partnership with local indigenous communities to involve their interests and expertise in preserving the land’s future wellbeing and ecosystems’ health[25]. The provincial government has also pledged to establish new processes to allow individuals and organizations the ability to donate funds to preserve old-growth areas by purchasing existing timber licenses from current holders[25]. Further involvement and inclusivity of both governmental and individual entities can contribute to the conservation of old-growth forests[25].

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Connell, David J. (2016). "Old-Growth Forest Values: A Case Study of the Ancient Cedars of British Columbia. Society & Natural Resources". Society & Natural Resources. 28: 1323–1339 – via Routledge.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "History of Commercial Logging – British Columbia in a Global Context". Geography Open Textbook Collective. June 12, 2014.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Strain, Brendan (April 7, 2021). "Teal-Jones addresses Fairy Creek logging controversy". CTV News Vancouver Island.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Price, Karen (April 2021). "Conflicting portrayals of remaining old growth: the British Columbia case". Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 51(2) – via ResearchGate. line feed character in

|title=at position 53 (help) - ↑ Tattrie, Jon (January 16, 2020). "British Columbia and Confederation". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 Gorley, Al (April 30, 2020). "A New Future for Old Forests" (PDF). Government of British Columbia.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 "Old Growth Values". Government of British Columbia. November 2, 2021.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "State of the World's Forests" (PDF). State of the World’s Forests 2012. 2012.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 "Common Q&As about BC's old-growth forests". Ancient Forest Alliance. 2021.

- ↑ Harkema, John (March 2002). "The Retention System: Maintaining Forest Ecosystem Diversity" (PDF). Government of British Columbia.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Berman, Tzeporah (February 27, 2019). "Takin' It Back". BC Studies.

- ↑ Sawyer, Deborah (December 15, 2013). "MacMillan Bloedel Limited". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Pojar, Jim (March 17, 2021). "Old-Growth Forests of Fairy Creek, Vancouver Island, British Columbia" (PDF). Ancient Forest Alliance.

- ↑ Williams, Nia (June 7, 2021). "Factbox: Fairy Creek blockades: the dispute over logging Canada's old-growth forests". Reuters.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Fairy Creek Blockades". The Narwhal.

- ↑ Banner, Allen (2005). "Pattern, Process, and Productivity in Hypermaritime Forests of Coastal British Columbia" (PDF). British Columbia Ministry of Forests Forest Science Program.

- ↑ "BC Forest Facts". Canada's Log People. May 27, 2020.

- ↑ Cunningham, Scott (November 2, 2021). "B.C. old-growth: Province proposes 2.6M hectare logging deferral". CTV News Vancouver Island.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 19.6 19.7 Stevenson, Susan K. (2011). British Columbia’s Inland Rainforest: Ecology, Conservation, and Management. UBC Press. ISBN 9780774818513.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 D'Eon, Robert G. (2002). "Landscape Connectivity as a Function of Scale and Organism Vagility in a Real Forested Landscape". Conservation Ecology. 6(2) – via Ecology and Society.

- ↑ D'Eon, Robert (May 2005). "The influence of forest harvesting on landscape spatial patterns and old-growth-forest fragmentation in southeast British Columbia". Landscape Ecology. 20(1): 19–33 – via ResearchGate.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Baldwin, Lyn (May 2007). "Bryophyte responses to fragmentation in temperate coastal rainforests: A functional group approach". Biological Conservation. 136(3): 408–422 – via ResearchGate.

- ↑ Mellina, Eric (February 2011). "Stream habitat and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) physiological stress responses to streamside clear-cut logging in British Columbia". Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 35(3): 541–556 – via ResearchGate.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Matsuzaki, Eiji (2013). "Carbon stocks in managed and unmanaged old-growth western redcedar and western hemlock stands of Canada's inland temperate rainforests". Library and Archives Canada – via Library and Archives Canada.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 "Government taking action on old-growth deferrals". BC Government News. November 2, 2021.

| This conservation resource was created by Course:CONS200. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |