Course:CONS200/2020/Environmental Impacts of the Rio Summer Olympics 2016

Introduction

In 2016, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil became the first South American country to host the Summer Olympics[1]. Bidding for the privilege to host 205 competing countries is a massive and costly undertaking, but also a unique opportunity for a country to showcase its capabilities[1]. Attracting a worldwide viewership, a country's best culture, infrastructure and natural beauty are put on display in a spectacle of parades and fireworks[1]. The environmental effect of such a massive world-wide endeavour is immense.

Due to a contemporary shift towards environmentalism, there is pressure on host cities to improve both aesthetically and emissions-wise[2]. Of course, the genuine integrity of these changes is hindered by intrinsic costs as well as the need to meet infrastructure standards of such a large event[1]. Rio had a number of goals, including reducing single-passenger vehicles, drastically reducing CO2 emissions and other pollutants, and cleaning the heavily trafficked natural water features in which events were to take place[3]. The effectiveness of these goals on key sustainability issues such as sustainable infrastructure, water quality, and carbon emissions is still a matter of debate.

Preparing for the Rio Olympics

Initial Blueprint of Environmental Solutions

Before the event, Rio was required by the IOC (International Olympic Committee) to address the environmental impacts of the Olympic Games[4]. A list of environmental issues was determined through this, that the Olympics and Paralympics were to be based around[5]:

- Water treatment and conservation

- Environmental awareness

- Use and management of renewable energy

- Games neutral in carbon, air quality and transport

- Protection of soils and ecosystems

- Sustainable design and construction

- Reforestation, biodiversity and culture

- Shopping and ecological certification

- Solid waste management

Thus, before the Games, the 'Sustainability Management Plan' was developed, aiming to expand on the issues above. This included[5]:

- Planet - reducing environmental impacts of projects relating to the Rio 2016 Games,

- People - inclusively offering the Games to people, regardless of background,

- Prosperity - economic development of the city of Rio de Janeiro.

The 'Sustainability Management Plan' was a compilation of different plans to solve the identified issues, including plans to improve transportation through the expansion of subway systems and plans to improve construction through urban redevelopment[4]. The objective of this was to reduce the environmental impact of projects related to the Games and the environmental footprint of projects and operations[4]. Public support for environmental issues regarding the Olympics was also maintained, with bidders for the Olympics stating that the Games would speed up the implementation of sustainability projects relating to air quality, environmentally sensitive sites, and waterways[6].

Pre-Olympics Water Quality at Guanabara Bay

Guanabara Bay, the second largest bay on the coast of Brazil[7], was one of the main sources of concern in relation to water quality due to its close proximity to where aquatic sports were to be held in the Games[7][4]. Guanabara Bay was constantly polluted with domestic liquid waste and industrial waste, which caused an increase of phosphorus and nitrogen in the water[7]. This was related to increases in pathogenic organisms in the water[7]. Adding to this, it was revealed that in 2007, Rio only treated 21% of its wastewater to secondary treatment levels (usage of aerobic bacteria to consume solids and organic compounds in the water)[4][8]. 44% received primary treatment (mechanical process removing compounds floating on the water)[8], and about 35% was let loose into open waters with no treatment[4]. The untreated waters raised a concern on the effects of raw sewage on the human body, including possible, but unknown, acute and chronic diseases through exposure to human feces, associated with such waters[9]. A proposed solution for this was through the Sustainability Management Plan, where it planned on improvements to sanitary facilities in the Rio metropolitan area[2] by proposing that sewer infrastructure would be built throughout the city, and at least 80% of sewage would be treated to secondary treatment levels before the start of the Olympic Games[4].

Sustainable Infrastructure

Recognizing that sustainable construction was important, the Sustainability Management Plan established guidance on ensuring construction of the Games would have little impact on the environment[10]. This was carried out through maximizing use of existing venues, attentive design and construction for new venues and maintaining high environmental standards during design and construction[10]. For construction, Rio 2016 collaborated with two companies: Municipal Olympic Company (EOM) and the developers of the Olympic Golf Course[10], to collaborate with their sustainable construction work[10]. The collaboration included solutions such as weekly meetings regarding sustainability strategies for the Olympic Park, collaborating with EOM to develop sustainability strategies and goals for temporary arenas concerning water, energy, materials and waste, and reviewing design blueprints and sustainability reports during all project phases[10].

Sustainable plans for transportation was also developed[10]. The target of the system was to ensure safe, fast and reliable transport for 100 per cent of spectators and workers of the Games[5]. This was reinforced by venues not having parking spaces[10]. Through investments by the state and local governments, this plan aimed to have 60% of transport done with public transport by 2016[10]. This was to be done by optimizing the routing of the Games for buses and light vehicles used for athletes, technical officials, media, Olympic and Paralympic family transport[10]. This would ensure the lowest possible fuel consumption and therefore lower carbon emissions[10].

Reducing Carbon Emissions of the Games

In addition, a plan which addresses the possibility of carbon emission through the Games[10] was formed. Initially, the plan aimed to reduce carbon emissions by 18.2% below 2011 levels by 2016[4]. Three key components of reducing the carbon footprint of the Games were developed, which were[10]:

- Understanding and measuring the carbon footprint of the Games

- Reducing Rio 2016 carbon footprint through avoiding emissions at the source, reducing emissions through efficient measures, and replacing unavoidable emissions through the substitution of conventional systems with lower carbon usage

- Compensating emissions from operations and spectators through technological mitigation, and compensating emissions from venues and construction through environmental restoration efforts

The main approach of these points was to view Rio 2016 as a project, rather than an organization[10]. These were to be implemented by carefully observing the project and removing any potential emissions through strategic planning and procedures[10]. Solutions were planned by Rio 2016, namely[10]:

- Avoiding emissions through attentive planning

- Reducing carbon through strategic design processes

- Substituting fossil fuels with renewable, alternative fuel sources

What happened during the Rio Olympics?

Air Quality and the Bus Rapid Transit System

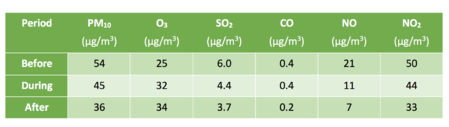

Rio 2016 was praised by many researchers for their air quality control during the Olympics. Concentrations of most pollutants decreased during the Olympics and continued to plummet it ended (Table 1) [2]. During the Olympics, Rio was able to maintain its concentrations of particle matters below the air quality standards of either the Brazilian government or US Environmental Protection Agency, a monumental achievement for Rio as it normally faced about 81 violations annually[3].

The World Resources Institute attributed Rio's improved air quality during the Olympics to proactive government policies and projects[4]. In preparation for the Olympics, the Brazilian government built new Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) lines that stretched over 90km and successfully improved suburban trains and metro lines[5]. As a result, the BRT increased 36% of daily trips made by public transportation during the Olympics, benefitting almost 1.5 million passengers daily[2]. BRT also succeeded in decreasing the average travel time by half for 65% of its passengers.

However, upon closer inspection, the new BRT lines were criticized because they were built in accordance to tourists’ and athletes’ interests[6]. The majority of the lines were designed to transport tourists and athletes to game locations, hotels, or the airport[6]. No BRT lines led to employment areas, preventing lay-citizens in the working class from using the transit system. Essentially, the BRT was only developed to support tourism during the Olympics, not as a sustainable public transportation system for Rio citizens. The Rio Olympics Committee also promised to extend its existing metro lines, with the addition of the Linha 4, to accommodate the city’s visitors[7]. However, the line was then only made available to tourists who bought Rio’s Olympic day pass that cost R$25, intentionally excluding Rio residents[7].

Why were the BRT and metro lines exclusive?

Rio's economic challenges forced its Olympics infrastructures to be exclusive[8]. Leading up to the Olympics bid in 2009, Rio claimed that it found a new oil field that could potentially generate at least $18 billion in profit for the city[9]. This money was going to help Rio develop new sustainable infrastructures for the Olympics and Rio residents in the future[8][9]. However, the oil extraction was much more difficult than anticipated[8]. Rio was then left with the only option to capitalize on Olympics exclusivity and tourists' luxurious desires by making its new transportation system convenient only to paid customers[8][9].

Water Quality at Guanabara Bay

Water sanitary in Rio, especially in the Guanabara Bay area, also suffered from the Olympics. Promising to clean up 80% of the bay was one of the major determinant factors that won Rio its opportunity to host the Olympics[10]. However, as the Rio Olympics Opening Ceremony neared, it became clear that this promise would not be followed through[11]. Guanabara Bay is directly linked to Rio’s sewage system, which is responsible for receiving 78% of Rio’s domestic wastes[11]. One year before the Rio Olympics, large amounts of untreated domestic and industrial wastes were still inputted into the bay[11], not only risking people's health but also the local aquatic biodiversity[12]. While this posed many health risks to athletes and some were advised to skip the Games[12], the Rio Mayor disregarded the clean-up of Guanabara as “a Brazil problem, not an Olympic problem” (p. 195)[7].

With hopes of building 8 new water treatment facilities, Rio fell short with only 1 operational clean water facility when the Games started[8]. Less than 2 months before the Games, the governor of Rio pled for financial support from the Brazilian government to prepare for the Olympics water sports[8]. Eco-barriers, floating nets designed to prevent large particles from flowing into the bay, were placed across all 17 rivers that feed into the bay[8]. In addition, dozens of boats and helicopters were tasked to find and remove trash in the bay during the time leading up to the Olympics[8].

Enlarged Carbon Footprint

Keeping in mind its carbon footprint, Rio implemented some attempts to reduce the Olympics' CO2 emissions such as using energy efficient LED lighting in its infrastructures and developing the Bike Rio program to promote biking during the Games[13][14].

However, Brazil welcomed a record of 6.6 million foreign tourists and over 11,000 athletes for the Olympics[14][15]. These flights emitted at least 2,490 kilotons of CO2eq, just within 12 days of the mega-event (Figure 1)[5]. This amount of CO2eq is equivalent to what half a million cars produce in an entire year[16].

Approximately 200 venues were used for the Rio Olympics[5], only 32 of which were dedicated to competitions[17]. Despite the fact that many of the venues already existed and only needed refurbishment, an estimated 720 kilotons of CO2eq emissions were released into the atmosphere in 2016[5]. Other large contributors of CO2eq emissions were operations (catering, accommodation, transport, etc. of athletes and officials) and legacy projects construction (cleaning up Guanabara Bay, planting trees, etc.[5]. Figure 1 shows the estimated details of CO2eq emissions contributors during the Rio Summer Olympics.

What happened after the Rio Olympics?

Ineffective Use of Infrastructure

Before the Games, $10.76 billion was allocated for Olympics infrastructure [15]. The budget covered city development and public transport to help decongest the city[15]. But after the Games, many infrastructures were abandoned[16]. For instance, the Rio 2016 golf venue became the city’s first public golf course. However, after the Games, the golf course struggled to attract players and is now abandoned[17]. The Olympic Park, which attracted 150,000 people during the Olympics, is in a state of disrepair and has been left deserted after failing to entice new operators following the conclusion of the Olympics as well as remains off-limits to the local community[17]. After the Rio Games, the Maracana Stadium, which underwent significant renovations, was also subject to looting[17].

Housing infrastructure was necessary to host the Rio Olympics to accommodate athletes and a large number of spectators. The Olympic Games allowed Rio to formulate the housing plan, which required the relocation of thousands of residents to construct housing that met the city’s affordable housing needs[18]. After the Games, the Olympic village was a costly housing option for local inhabitants and is now abandoned [16][17].

Rio used the Olympic Games as a significant tool in the advancement of public transport infrastructure[19]. The new and refurbished roads created a vital transport network across the city, improving life for working-class Rio residents[19]. The roads are viewed as the only positive Olympic legacy. The Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) lines were important in shifting Rio into a sustainable path. However, the problem with BRT was that it replaced previously planned transit alternatives, and impeded integrated transport solutions; BRT lines restructured Rio’s mobility pattern[19]. Principally, the BRT is not used by low-income residents but by the wealthy neighbourhood of Barra da Tijuca, the primary site of the 2016 Olympic competitions. Numerous protests were held complaining about the enormous cost spent for the Rio Games[20].

Decreasing Water Quality

Historically, Rio hasn’t always experienced water quality problems. Some say water pollution issues started in the 1950s when oil refineries were running unchecked[21]. After the Games, water quality worsened because the population in Rio is growing at an excessive rate, even though there are water treatment programs[22].

Water conservation and treatment remain top sustainability initiatives in Rio, but economic and political difficulties continue to prevent the city from achieving water cleanliness[22]. Rio’s financial situation, the slow government legislation, and inadequate resources slowed the progress required to allocate resources to a sewage sanitation project[22]. The Brazilian government implicated in corruption scandals, which has made it difficult to account for the water-treatment projects[23]. The failure to clean up Guanabara Bay during the Rio 2016 Games was a lost opportunity for the government and residents because the Rio Olympics offered an opportunity for Brazil to secure funds to solve water pollution concerns[24].

Efforts in Reducing Carbon Emission

No matter how many projects are implemented, hosting the Olympic Games will always have a huge toll on the environment. Carbon offsetting is important because it compensates for emissions made elsewhere and it is cost-effective[13]. The Rio 2016 organizing committee said 3.6 million metric tonnes of greenhouse dioxide, the total amount of emissions that the Olympic and Paralympic Games were projected to produce, would be offset[25]. This consisted of all emissions from operations, venue and infrastructure development as well as spectators' flights and consumptions. To further reduce carbon emissions and increase energy efficiency in fields such as agriculture, industry, and infrastructure, 2 million metric tons of carbon would be offset by Dow Chemical, Rio 2016’s official carbon partner, through technology[25]. The remaining 1.6 million metric tons of carbon would be offset by the Rio state government[25]. The committee claimed that this amount will be partly balanced by planting trees, while the remainder will be covered by conservation efforts in the Atlantic Forest, which stretches along the coast of Brazil, and other initiatives aimed at promoting a low-carbon economy[25].

Solutions to Key Sustainability Issues

Achieving Sustainable Infrastructure

The degradation of infrastructure is a hallmark of the Olympic Games[22]. Thorough and extensive planning is the best way to counter this issue and has successfully been implemented in the past[22]. For example, Atlanta and Sydney were both able to continue using Olympic stadiums to accommodate local sports teams after the Games had ended[22]. Rio has developed significant issues surrounding water quality and sanitation following increased development amidst a dire population explosion[22]. Investments in improving existing water facilities would be an example of sustainable infrastructure supporting both the environment and local populations. Rio had admirable goals, but unfortunate volatility in oil markets, the basis of Brazil’s economy, left Rio wanting for money at a crucial point[22]. Sustainable long term projects such as water quality were thus sidelined for ineffective projects such as the poorly planned subway system to generate profit necessary to sustain the Games for its duration[22].

Future Sustainability Goals (Tokyo 2021)

The next summer Games are scheduled for 2021 in Tokyo. Japan has a highly sophisticated environmental plan in place focused around robust concepts with major carbon emissions goals[26]. Tokyo 2021 plans to succeed in saving energy, using renewable energy sources, and offsetting inherent CO2 emissions and achieve zero-carbon output[26]. To accomplish zero waste, Tokyo is organizing to recycle 99% of items specifically used for the Games; even recycling normal household items to create Olympic podiums [26]. It also plans to reuse rainwater and develop on the concept of "greening", where local native species are preserved and planted to promote biodiversity[26]. Having seen the failures of the past, Tokyo will strive to minimize the building of new venues as much as possible, while utilizing its already extensive public transportation network[26].

Public Input Regarding Sustainability and Effective Use

Legislating public consultation as an integral component of Olympic licensing systems, specifically to include new community stakeholders, would boost environmental accountability[27]. Organizing committees are pressured by societal and governmental factors to focus on the economic side of large development proposals. This ignores the fundamental benefits achieved in researching how these changes will affect and influence local populations[27]. Projects would be significantly different, and perhaps more sustainable and economically viable moving forward if a democratic system was in place[27]. Expanding upon public input via enforcement protocols highlights the key concept of oversight mechanisms. The lack of effective environmental policy enforcement is largely due to a disconnect in the hierarchy of the Olympic committees. Promises made in the bidding process are seen as a success if they are even partially completed, so the IOC needs to implement a process for reprimanding unfulfilled promises[27].

Conclusion

The Rio 2016 Summer Games brought the world to the developing country of Brazil. Pressured by demanding social and committee imposed environmental standards, promises were made but not necessarily kept. The IOC conducted an environmental impact assessment which highlighted the need to reduce environmental impacts, improve water quality, and made clear preconditions for the Games[5]. Rio took these in stride, convincing the IOC that they were in control of the situation. When the Olympics were over, the reality was complicated. The inherent size of the event resulted in thousands of kilotons of unnecessary C02 emissions[28], despite an overall improvement in localized air quality[29].

Rio greatly improved its public transportation, helping to eliminate single-use vehicles[30]. However, the location of these newly built routes where not practically applicable to Rio moving forward and ended up being another example of wasted infrastructure[6]. Rio's water quality was another highly publicized issue around which many promises were made[31]. The goal of cleaning up 80% of Guanabara Bay was never reached, potentially putting athletes in danger and revealing the ineffective application of Rio's sustainability goals. There are many potential solutions to mitigate the environmental impacts of future Olympic Games, with high hopes and big promises made ahead of the upcoming 2021 Tokyo Summer Games. The key to success, however, is the implementation of strict oversight mechanisms and increased public stakeholder input[32][27]. Accountability for promises made is the most important idea for future success in reducing wasted infrastructure, poor water quality and carbon emissions.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Rowberg,Rincker, K, M (2019). "Environmental Sustainability at the Olympic Games: Comparing Rio 2016 and Tokyo 2020 Games". European Journal of Sustainable Development.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 The 2016 Olympic Games: Health, Security, Environmental, and Doping Issues. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R44575.pdf: Congressional Research Service. 2016.CS1 maint: location (link)

- ↑ Summer Olympic Games Organizing Committee. https://library.olympic.org: Sustainability management plan: Rio 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games. 2013.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 "The 2016 Olympic Games: Health, Security, Environmental, and Doping Issues" (PDF). Congressional Research Service: 13–20. August 2016.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Summer Olympic Games Organizing Committee (2013). "Rio 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games (Version 1)". Sustainability Management Plan.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Boykoff, J. (2017). Green Games: The Olympics, Sustainability, and Rio 2016. In ZIMBALIST A. (Ed.), Rio 2016: Olympic Myths, Hard Realities (pp. 179-206). Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/10.7864/j.ctt1vjqnp9.12

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Fistarol, Giovana; Coutinho, Felipe; Moreira, Ana; Venas, Taina; Canovas, Alba; De Paula, SeRgio (November 20, 2015). "Environmental and Sanitary Conditions of Guanabara Bay, Rio de Janeiro". Frontiers in Microbiology. 6 – via Gale.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "How Wastewater is Treated". Metro Vancouver.

- ↑ Eisenberg, Joseph; Bartram, Jamie; Wade, Timothy (October 2016). "The Water Quality in Rio Highlights the Global Public Health Concern Over Untreated Sewage". Environmental health perspectives. 124 – via NCBI.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 10.14 Summer Olympic Games Organizing Committee (2014). "Embracing Change". Rio 2016 Sustainability Report.

- ↑ De La Cruz, Alex Ruben Huaman; Calderon, Enrique Roy Dionisio; França, Bruno Bôscaro; Réquia, Weeberb J.; Gioda, Adriana (April 15, 2019). "Evaluation of the impact of the Rio 2016 Olympic Games on air quality in the city of rio de Janeiro, Brazil". Atmospheric Environment. 203: 208 – via ScienceDirect.

- ↑ Rio 2016 (2016). Rio 2016 Carbon Footprint Report (PDF). Rio de Janeiro. p. 3.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Mabee, Warren (February 16, 2018). "In a World Striving To Cut Carbon Emissions, Do the Olympics Make Sense?". Smithsonian. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- ↑ Moraes, Tais (December 7, 2011). "Take two for Rio de Janeiro's bicycle rental program". ZDNet. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Fonseca, Pedro (16 April 2014). "Brazil unveils $10 billion infrastructure budget for Rio Olympics". Reuters. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Davis, Scott (5 March 2020). "What abandoned Olympic venues from around the world look like today". Business Insider. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 "Rio Olympic venues already falling into a state of disrepair". The Guardian. 10 February 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ↑ Simpson, Mariana Dias (2013). Urbanising favelas, overlooking people: Regressive housing policies in Rio de Janeiro’s progressive slum upgrading initiatives. Development Planning Unit, University College London.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Kassens-Noor, Eva; Gaffney, Christopher; Messina, Joe; Phillips, Eric (19 December 2016). "Olympic Transport Legacies: Rio de Janeiro's Bus Rapid Transit System". Journal of Planning Education and Research,. 38: 13–24.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- ↑ Gold, John R.; Gold, Margaret M. (2016). Olympic Cities City Agendas, Planning, and the World’s Games, 1896 – 2020. London: Taylor & Francis Group.

- ↑ Branch, John (27 July 2016). "Who Is Polluting Rio's Bay?". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 22.6 22.7 22.8 Trendafilova,Graham,Bemiller, Sylvia,Jeffrey,James (2018). "Sustainability and the Olympics: The case of the 2016 Rio Summer Games". the Journal of Sustainability Education.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ Khazan, Olga (31 March 2016). "What Happens When There's Sewage in the Water?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ↑ Consumer News and Business Channel (30 July 2015). "Water in Brazil Olympic venues dangerously contaminated". CNBC. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Hardcastle, Jessica Lyons (3 November 2014). "Rio 2016 to Offset Olympic Games' Entire Carbon Footprint". Environment + Energy Leader. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 "Sustainability". The Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Game. 2020.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 Pentifallo,VanWynsberghe, Caitlin, Rob (2012). "Blame it on Rio: isomorphism, environmental protection and sustainability in the Olympic Movement,". International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics. 4:3: 427–446.

- ↑ Rio 2016 (2016). Rio 2016 Carbon Footprint Report (PDF). Rio de Janeiro. pp. 1–77.

- ↑ De La Cruz, Alex Ruben Huaman; Calderon, Enrique Roy Dionisio; França, Bruno Bôscaro; Réquia, Weeberb J.; Gioda, Adriana (April 15, 2019). "Evaluation of the impact of the Rio 2016 Olympic Games on air quality in the city of rio de Janeiro, Brazil". Atmospheric Environment. 203: 206–215 – via ScienceDirect.

- ↑ World Resources Institute (n.d.). "Rio's New Bus Rapid Transit Line Improves Life for Millions". WRI.org.

- ↑ Gaffney, Christopher (December 28, 2018). "Can We Blame it on Rio?". Bulletin of Latin America Research. 38: 267–283 – via Sage Publications.

- ↑ Pereria, De Conto, maria, Silva, GISELE, Suzana (2014). "Public participation in Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and Major Sports Events: A Comparative Analysis of the London 2012 Olympic Games and the Rio 2007 Pan American Games" (PDF). Rosa dos Ventos. Vol 6: 448–507.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

| This conservation resource was created by Course:CONS200. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |