Course:ASIA319/2022/"Fashionable" (潮)

Introduction

Fashionability (or trendiness) (潮) refers to a short-lived popularity of a cultural object, entity or behaviour that is widely adopted by a cultural or social group. For instance, a particular type of clothing or a colloquial phrase can become fashionable or trendy in a given period of time. Generally, objects and behaviours that are seen as in vogue are perceived positively, especially by the general public. However, given that trendiness is innately ephemeral, trends tend to lose their appeal fairly quickly. In the context of Chinese culture, trendiness is often associated with young people (30 and under) and usually refers to fashion styles, neologisms, and pop culture artifacts (e.g. films, songs, viral videos, etc.).

Dictionary meanings and historical definitions

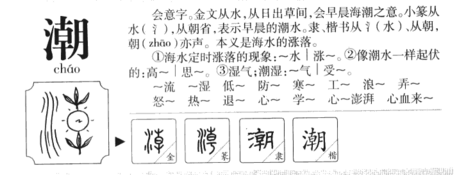

The word 潮 (cháo) has an etymological root of the sea water rising from the morning tide.[1] It is a phono-semantic compound composed of two components: the radical on the left氵/水 (shuǐ; water) and the character on the right 朝 (cháo; to face; direct, facing; dynasty; morning).氵expresses the meaning of the word, while 朝 indicates the sound of the word.[2] 潮 can be used as a noun, verb, and adjective. It has various usages and meanings: when used on its own within the contemporary context, 潮 can mean current, fashionable, trend, popular (潮流; cháoliú), or Chaozhou culture (潮州文化; cháozhōu wénhuà).[3] Chaozhou is a city in the eastern Guangzhou province of China. On the other hand, 潮 is usually used in relation to weather: cold wave, hot wave, tide, wet, moist, damp, flow, and waves. However, it can also be referred to as a way of thinking about a characteristic of history (Zeitgeist).[4]

Genesis of "Fashionable" and associated words

潮 can function on its own as the meaning of fashionable, a trend, and popular, but it can also be paired with the character 流 (liú; flow), to make up the word "潮流" (cháoliú; trend). You can simply assume that 潮 is an abbreviated version of 潮流. When thinking of 潮流, it is usually associated with fashion, however, 潮流 isn't simply about how fashionable one looks (i.e. outfits, clothing, earrings, etc.), but can also refer to one's day-to-day essentials (i.e. furniture, electronics, utensils, pencils, etc.).[5]

Historically, 潮流's first appearance was derived from the English word "trend," during the early 90s by the Japanese. Before long, the word became popular in Taiwan and Hong Kong. By the year 2000, China began to take upon this word. Many of these people were known as "潮人[6]" (cháo rén; trendsetter; lit. trendy person) in China, and most of them were fans of athletic shoes and board shoes.[7] However, China's trend or so-called "fashionable" was far comparable with those in Japan. Japanese brands such as BAPE, MMJ, and VISVIM were famously known globally during the time when China started to pick up the term 潮流. In other words, around the year 2000, the word 潮流 was highly associated with these Japanese brands. Although China had a late start on taking upon this word, just within a decade, the word 潮流 previously exclusively associated with shoe fans is now exploited and related to various genres, from new brands to new designs of clothing, accessories, utensils, technology, and media platforms.[5]

Associated words

新潮:refers to a new wave or a new trend. In other words, the most recent popular or trendy item or topic.

潮流:refers to current trends or topic. 潮 is an abbreviated version of 潮流.

主潮:refers to the main trends. A metaphor for the main tendency of how things will develop or change.

潮人:refers to a trendsetter, a person who lead the trend.

潮牌:refers to brands that consists of original design, creativity, ideas, style, and lifestyle.

潮品/潮物:refers to trendy products. "潮品" is also a name of a media platform specifically for sharing trendy fashion produced by a Hong Kong company, Stepcase.

潮服:refers to trendy clothings.

潮语/流行语:refers to catchword and/or fashionable language. It appears to be a lexical phenomenon, reflecting the issues and things that are of general interest to people in a country or region at a time, echoing the changes within that society.[8] Note that it can sometimes be referred as slangs.

国潮:A portmanteau of "中国" (zhōngguó; China) and "潮流" (cháoliú; trend), is a movement created in mainland China that incorporates traditional Chinese elements in its design characteristics. It is meant to be recognized and its related fashion items worn by people for its unique Chinese identification.[9]

潮男:refers to urban beautiful men. Historically, referring to men that spend both their time and money lavishly on materialistic things, perceived negatively. However, it is currently referred to stylish and handsome young male, who still spend money on materialistic things such as fashion, but only under their affordable financial range, and it is perceived as neutral.

潮剧/潮腔/潮调:refers to a type of traditional Chinese opera. There are two categories, (1) singing, (2) repertoire. Popular in the eastern Guangdong, southern Fujian, and Taiwan. Developed from the opera of Song and Yuan Dynasty and became popular in the Ming Dynasty.[10]

"Fashionable" in Chinese contemporary culture: meanings and implications

The explicit use of 潮 denotes being in fashion or trendy. It does not always mean the most popular but more so describes an aesthetic that is considered to be fashionable. For one user, 潮 is not something achieved through exorbitant spending. It does not mean to follow but rather to lead a trend and a keenness on individuality.[11] For another user’s explanation of 潮: it is an attitude and /or an avant-garde spirit that is willing to explore or embody a particular style. 潮 can be used to describe people, objects, locations, ideas (brands), movements, or even time periods. However, in order to attain the attribute of 潮 there must have been some novel idea or creativity involved in the process.[12]

The connotation of 潮 is "非主流" (fēizhǔliú) or nonmainstream. This has a near opposite sense of being trendy; however, it should be emphasized again that the quality of being mainstream is not essential to 潮. The difference between 潮 and nonmainstream is subtle. Where fashionableness is more accepted by the perceivers of the style, nonmainstream has a subculture overtone to it; hence, it is not as accepted by the majority to adopt as a trend. Nonmainstream often utilize elements that are exaggerated and eye-catching but in essence, they are different. Examples of nonmainstream could be facial tattooing, unusual hair coloring often with exaggerated volume, or heavy make-up.[13]

The word 潮 also comes with an implication of influence. 潮 and fashion are often synonymous because expressing 潮 is often done through fashion.[14] A trend is not easily perpetuated simply by a few ordinary people as it relies on influential individuals in society to set a fashionable trend in motion. Celebrities are the most common example of how to increase brand affinity as well as attract media attention.[15] These individuals are sometimes referred to as KOLs or Key opinion leaders. They are the respected figures in society that can influence the thoughts and actions of others, especially in their buying behaviours. KOLs differ from ordinary people through their social connections as they often have an expansive reach on social media platforms. Their stylistic expressions are often an example to mimic for their followers; thereby, facilitating fashion companies’ purchase conversion rate.[16]

Western or Non-Chinese Counterparts

An American counterpart to 潮 is the slang “hip”. It is sometimes mistaken to be the first half of the word “Hip-Hop”, a genre of music of African American origin, implying an urban music connection. However, it is actually of West African origin stemming from the nations of Senegal and the coastal Gambia. “Hip” is not exclusively an adjective but also a romantic idea. The truth of “hip” lies in not a catalog of facts but exists as literary and not always literal. Its original meaning is a term pertaining to enlightenment and can be traced to the “Wolof verb hepi (“to see”) or hipi (“to open one’s eyes”)”.[17] An English word of French origin is “vogue”. Vogue refers to the trend of the time. It is a gauge for fashion brands to evaluate patterns in the market. Consumer emotions can be created by developing around a trend that customers consider to be vogue. When fashion brands are said to be in vogue, it is able to draw emotional association to their brand, especially in young people.[18] A French word that is closely related to 潮 is “branché”. The word denotes both characteristics of “fashion” and “hip”. It could also be used to describe a fashionable person. Although, it is mostly used with a feminine connotation.[19]

The Multiple Meanings of the Keyword

The word 潮 has a radical of water. Its original use has to do with water and tides. In modern adoption of the word, it has generally been used as an adjective to describe developments in culture related to fashion and social issues, see associated words above. The various other usages of 潮 denote a trend relating to ideology, thought, movement, or pattern, such words are "思潮" (sīcháo; thought trend), "学潮" (xuécháo; student movement), "移民潮" (yímín cháo; immigration wave), and "涨价潮" (zhǎngjià cháo; price surge), here, 潮 is generally used as a noun. In daily life, it is most often 潮 (cháo) used to describe the natural phenomenon of dampness and condensation in a given environment. Such words formed are "潮湿" (cháoshī; damp), "返潮" (fǎncháo; get damp). Reminiscent of its original meaning, 潮 is also related to tides in water, or things that have a tidal nature, which include words like "浪潮" (làngcháo; tidal wave), "潮水" (cháoshuǐ; tidal water), "低潮" ( dīcháo; low tide/low ebb), "高潮" (gāocháo; high tide/high ebb).[20]

Transferred, distorted, or subverted meanings of the Keyword

The genetic meaning of 潮流 (cháoliú) according to the scientific definition in oceanography is the natural occurrence of periodic movement of seawater due to the gravitational pull of the moon and sun. Popular cultural derivation of the word trendiness borrows from the come-and-go nature of its literal meaning. Metaphorically speaking, trends behave like tides, there are external influences stemming from the tidal forces of the moon and sun. Trends occur and come to pass just as tidal waters behave; the motion is ceaseless just as the arrival of new trends.[21]

The word 低潮 (dīcháo) has been transferred into the realm of psychology. Specifically, it has been associated with a psychological condition meaning a mental slump. In psychology, the human body experiences intellectual, emotional, and physical cycles. These cycles can have periods of emotional highs or lows. Low ebb periods show signs of lowered mental endurance and mood. It also comes with forgetfulness and the mind becomes more prone to distractions.[22]

A common modern usage of 高潮 (gāocháo) is to express an emotional state, as a metaphor for sexual orgasm. The experience is described as a euphoric bio-physiological sensation accompanied by but not exclusive to ejaculation, blushing, or convulsions having had sufficient sexual stimulations, usually in the erogenous zone.[23]

Values of "Fashionable": Social, cultural, and political problems

Issues of Consumerism that comes with 潮流 culture

One of the social issues that arise with the increase in popularity of 潮流 (cháoliú) culture, and the usage of the term 潮, is its promotion of disposable consumption within the fashion industry. As of 2019, China is the world's largest fashion market. Rapid urbanization and the growth of the middle-class population have increased the spending power of the population, as well as the younger generations who are increasingly fashion-conscious and willing to spend money on fast-paced trends; ultimately expanding the fashion markets for both high-end and low-end clothing.[24] The increased popularity of digital platforms, such as TikTok, amongst the younger generation has accelerated this phenomenon, as viewers are able to see the changing trends instantly and constantly.[25] As a result, to keep up with the rapidly changing 潮流 culture, China has become the world's largest source of fast fashion merchandise. Although foreign brands have high manufacturing rates in China, the majority comes from the contribution of domestic Chinese fashion companies. As brands try to keep up with the 潮 trends, they heavily rely on fast, cheap clothing production. As a result, these pieces go out of style at a high-speed pace and are deemed "undesirable" very quickly, ultimately disposing of approximately 26 million metric tons of textiles annually.[26]

The rise of 潮人恐惧症 (cháorén kǒngjùzhèng; hipster phobia)

As the fashion industry expands in contemporary Chinese societies, the term 潮人恐惧症 has been coined by Chinese netizens.[27] This refers to the uncomfortable feelings people experience when they visit occasions and venues populated by young, well-dressed people, at times even feeling inferior, tense, and embarrassed in these environments. The term is frequently used within the online space. It derives from particular qualities of Chinese Internet culture that enjoys wordplay and creating new keywords; therefore, 潮人恐惧症 is more accurately used to describe a shared emotional experience rather than a medical issue. With the increased accessibility to digital platforms, the general public is becoming more aware of the rapidly changing 潮流 trends in the fashion industry through popular content such as street photography culture and “OOTD (Outfit Of The Day)” social networks.[28] As a result, people are more often experiencing a cultural shock in their fashionability as the trends that were once only visible on TV screens and in fashion magazines are now expanding their circles, appearing more frequently in daily life. With this phenomenon, comes the socials issues of “容貌焦虑” (róngmào jiāolǜ; appearance anxiety) as visual culture increasingly becomes the norm, and more people begin to struggle with their self-image, desperate to keep up with the fast-paced fashion trends. As the results of a questionnaire survey conducted by the China Youth School Media showed, over 60% of college students struggle with a certain level of Appearance Anxiety. Especially prevalent within the young 潮人 circles, there is an oppressive sense of this social gaze in which keeping up with the fashion trends has become a social status.[29]

The Redefining of 国潮 in relation to Foreign brands

潮 culture has led to the rise in popularity of 国潮 (guócháo) fashion within the industry. The term expresses the rise of Chinese native fashion trends that can be categorized under "China Chic." It has ultimately expanded the concept of "Made in China" from a straightforward manufacturing locator to a representation of Chinese culture and aesthetics created by and for the local Chinese.[30] In addition, the rise in 国潮 fashion has helped improve the qualities and design of native Chinese brands. 国潮 designs often incorporate some Chinese cultural elements that are often reflected in popular fashion trends, such as featuring traditional Chinese patterns and characters. The notion of 国潮 is spreading to several different industries, most prominently the cosmetic and food industries, which incorporate 国潮 qualities through the usage of traditional Chinese symbolic elements into their product packaging.[31]

As a result, the rise in this trend has impacted the consumer patterns and values of the Chinese people, especially its influential younger population. From heavy interests in pop culture and trends originally from countries such as Japan, South Korea, and the Western world, the younger generations have developed a demand for traditional Chinese style where many 潮人 (cháorén) have been seen incorporating traditional Chinese garments in their daily fashion. In addition, Chinese consumers prefer domestic products over international ones as they have developed a strong national cultural confidence. As attitudes towards foreign brands evolve and the perceptions of local Chinese brands improve, it is becoming increasingly difficult for foreign fashion retailers to enter the saturated Chinese fashion market, to the extent that it is estimated that approximately 48% of foreign brands entering China will fail within two years.[32] The rapidly changing 潮 fashion trends and the unique usage of China's native digital platforms make it even more difficult for foreign brands to understand Chinese consumers' preferences. For example, in early 2021, foreign brand conglomerates such as Nike and Adidas received large controversy over comments the brands had made regarding the labour conditions in Xinjiang China, to the extent in which backlash was prompted by the Chinese government to prevent foreign brands in tainting native brands in a negative light, ultimately initiating a boycott protest for these fashion brands and products.[33] This highlighted the influence 国潮 culture has over Chinese political discussions, and the impacts Chinese nationalism has over Chinese consumer markets. Furthermore, in the digital space, the trend of 国潮出海 (guócháo chūhǎi; China chic goes overseas) has been on the rise, as the younger generations share their traditionally centered fashion on online platforms, in a way exporting their culture to a foreign audience.[34]

Scholarism and the Propagated Dissent Against the Chinese Central Government

Scholarism or “学民思潮” (xuémín sīcháo) is a defunct student-organized movement in Hong Kong which sparked successive protests and formations of organizations like the Umbrella Movement and Demosistō. The aim of Scholarism was to bring about reform to Hong Kong’s educational curriculum and political policy, both of which had come under substantial influence from the Chinese Central Government since the late 2000s. Prevailing issues addressed by Scholarism pertained to the abolishment of the hegemonic, state-centric educational curriculum that was seen as indoctrinating - infused with propagandizing material. Other issues concerned China’s one country, two systems promise to Hong Kong as a condition of the 1997 handover as well as a democratic electoral system independent of CCP influence, developing a system for the protection of minority’s rights, and establishing Hong Kong’s own charter for the self-determination of its people and new socio-political order of the city.[35] Its prominent figure Joshua Wong, a then high-school school student who later founded the organization Demosistō, has been a contentious individual in the increasingly uneasy relationship between China and the West regarding the former’s handling of human rights issues, especially concerning its encroaching presence in the special administrative region. The absence of Wong’s leadership may represent a challenge to a sustainable movement in Scholarism and its subsequent organization, Demosistō.[36] However, Scholarism and its influence still reverberate in Hong Kong society. Prior to the outbreak of COVID-19, Western media focus had been heavily placed on the demonstrations in 2019 in Hong Kong against the Extradition Law Amendment. The recent development in Hong Kong’s passing of the National Security Law has in most cases quieted the publicly dissenting voices against the Chinese Communist Party’s rule. Nonetheless, the movement in the spirit of Scholarism may still be echoing in parts of Hong Kong and Chinese diaspora communities abroad.[37]

Coffee, Fast Food and the Desire for Romantic Love in Contemporary China: Branding and Marketing Trends in Popular Chinese-Language Literature is a piece of transcultural literary research that explores the important role of marketing and branding trends that have influenced China as well as the convergence of Western culture (i.e. coffee, food) and Chinese culture. Lena Henningsen listed an example of "for Chinese consumers, consumption of Western food is a means to link up with the world... suggest[ing] that their lifestyle and attitude to life is closer to urban centers [as compared to rural areas]."[38] This study has a strong connection with the word "fashionable; 潮," as it studies the importance of changing trends within the Chinese context and the reason why Chinese people had picked up the word 潮. In other words, to become closer to an urban world, or chase the West, those who adapt to the "Western" lifestyle in China are associated with the word 潮, referring back to associated words such as 潮人 (cháo rén), 新潮 (xīncháo), and 潮流 (cháoliú). Nonetheless, like said, the word 潮, doesn't only take on the meaning of fashion, it can also take on meanings of smaller items and necessities.

Contemporary Chinese Films and Celebrity Directors is a book on film study that examines various popular films and directors where these filmmakers have embedded diversifying and individualizing ideological trends into their manuscripts and films. Films such as Lost in Hong Kong by Xu Zheng and Tiny Times by Guo Jingming explore topics of not only cultural commodities, but also engage in social, economic, and political issues; which projects new and contradictory ideologies to audiences and fans.[39] Social topics that appeared in the Tiny Times can become hot topics among viewers and society, and these new ideologies presented within the film will, in turn, generate new trends. If referring to the word 潮, when these new ideas become popular and trendy, we can then consider it as a fashionable language.

The Design Theory of Contemporary “Chinese” Fashion is a research on design issues written by Christine Tsui. It features HE "和" as a symbolic and unique feature that makes Chinese fashion styles and designs stand out. There are three forms and/or meanings to the symbolic HE "和": (1) Implied Beauty in Aesthetics, (2) The Flat Form/straight cutting, and (3) The Spirit of Harmony as a spiritual value. Tsui argues that though there have been influences on fashion by the West, modern designers have adapted various unique/traditional Chinese fashion features (i.e. the 3 forms mentioned above). Her mention of a modern designer, Xiao Yu, featuring the black and golden colours takes on features of traditional Chinese landscape painting, and the usage of flat form/straight cutting in her designs portrays newly emerging fashion designs.[40] Connecting it with the word 潮, these newly emerging fashion designs featuring unique traditional "Chineseness" serves the new trendy topic within the fashion industry and consumers. Likewise, some internet celebrities (网红;wǎng hóng) in China dress up in traditional Chinese wear (汉服;hànfú) and upload it to their platforms to encourage and call for "Chineseness" in modern Chinese fashion industry. Therefore, featuring "Chineseness" in fashion designs can be considered a new trend not only within the fashion industry but also among consumers.

Among all three journals, there is an observation of different trends across multiple industries (i.e. business, film, fashion, food, consumer, games, cafe, etc.). There is a clear interaction that illustrates the word 潮 (trend, fashionable) is not only limited to the fashion industry as the word can also be seen and used in many topics and situations, depending on the context. Imagine speaking with a friend about cars, you might say Tesla is very 潮 (fashionable) in the sense that if someone owns a Tesla, they are very fashionable, trendy, and up-to-date. Similar to owning an iPhone 14. However, we must note that when something is associated with 潮, that topic/item will be trendy/a hot topic for only a short period of time (1-2 years), though can re-emerge after a few decades, especially fashion. Thus, since 潮 consists of, or, represents different trendy items and topics, it is used widely by Chinese speakers when referring to something that is current, trendy, and popular within a certain context.

Conclusion

The term 潮 is most likely a loan translation, or calque, which is a kind of word-for-word translation of the term wave in English, which has been historically used to refer to trends or fads. While both the terms 潮 and trendiness do not necessarily relate to fashion, especially with regard to clothing. 潮 as it is commonly employed in China generally speaks to the ways in which one dresses or clothes themselves and how they follow fashion styles that are considered in vogue. A consideration of the variations of the term, such as 潮人 (trendy person) or 潮服 (trendy clothes) speaks to the consumerist and materialist nature of this term.

Nevertheless, some of these associated terms, such as 潮男 (trendy man), have derogatory and negative connotations, which reflect a growing cultural apprehension towards 潮 and trendiness in general, especially since it is most often tied to youth culture. This is best reflected in the phenomenon called 潮人恐惧症 (or hipster phobia), a term coined by Chinese netizens, that refers to a sense of discomfort one feels when surrounded by young, fashionable individuals. These feelings are often characterized as anxiety or a sense of inferiority as a result of being next to these people.

Scholarly studies of 潮 have drawn connections to the growing trendsetting culture in China to western influences. Given the term's own etymological roots, there is indeed a strong tie between both cultures as they are linked to modernity, urbanity, consumerism, and materialism. Yet, as other studies have indicated, 潮 touches on aspects beyond fashion and can include popular films as well as other consumer products. Finally, there is a movement to emphasize the unique Chinese fashion sensibility that reflects distinct Chinese culture. Such a shift away from Western influences underscores a country that is gradually defining its pop-cultural landscape

This page primarily focused on the 潮 through the lens of the fashion industry within Chinese culture. Most prominently, it explores the different usages of the concept of “trendiness” such as its connotation of "非主流" and being eye-catching and unique, the issues that arise with the increasing values of 潮 including mass consumer waste, the rise of appearance anxiety, and the influences of Nationalism on fashion consumption. There are still various directions for future investigation on the topic of 潮. As 潮 fashion culture is on the rise in popularity, further exploration can be done in terms of the relation between 国潮 and Chinese nationalism. Conducting a further investigation into how the concept of 潮 plays a role in building 文化自信 (Wénhuà zìxìn: cultural confidence), and ultimately exploring the economic impacts “ trendiness” can have on modern Chinese culture.

References

- ↑ "Historical meaning of 潮". 康熙字典.

- ↑ "Meaning of 潮". Purple Culture.

- ↑ "潮 (汉语文字)". Baidu.

- ↑ "Meaning of 潮". Purple Culture.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "History of 潮流". Baidu.

- ↑ "潮人;trendsetter". Baidu.

- ↑ "板鞋; board shoes". Baidu.

- ↑ "潮语/流行语;fashionable language". Baidu.

- ↑ "国潮时代:什么是国潮?如何玩转国潮?". 知乎. 文创春秋. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ↑ "潮剧;Chinese opera". 在线汉语字典.

- ↑ "https://www.sohu.com/a/227623708_479926". 搜狐. June 8, 2018. External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ "「潮」到底意味着什么?". 知乎. December 15, 2016.

- ↑ "潮人". 搜狗百科. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ↑ "潮流". 搜狗百科.

- ↑ Leung, Vivienne; Cheng, Kimmy; Tse, Tommy (2018). "Insiders' Views: The Current Practice of Using Celebrities in Marketing Communications in Greater China" (PDF). Intercultural Communication Studies. The University of Rhode Island. 27 (1): 96–113.

- ↑ Zou, Yushan; Peng, Franke (Spring 2019). "Key Opinion Leaders' Influences in the Chinese Fashion Market". Fashion Communication in the Digital Age: 118–132. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-15436-3_11 – via Springer.

- ↑ Leland, John (2019). Hip: The History. HarperCollins e-books. pp. 9–23. ISBN 978-0060528188.

- ↑ Rajagopal, Ananya (November 3,2019). "Exploring behavioral branding: managing convergence of brand attributes and vogue". Qualitative Market Research. Emerald Publishing Limited. 22: 344–364 – via Emerald Publishing. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Définition Branché". Linternaute. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ↑ "与 潮相关的所有词". Collins. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ↑ "潮流". 文学网汉语词典. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ↑ "心理低潮期". 百度百科. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ↑ "性高潮". 快懂百科. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ↑ Stephanie, Yang (October 14 2020). "Fast Fashion in China: A Humanitarian Issue". Borgen Magazine. Retrieved November 10 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ Tanner, Ashley (June 4 2021). "Chinese Street Fashion: Avant-Garde Style Hits the Streets and Tiktok". Local Talk News. Retrieved November 10 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ The Collective (July 5 2019). "Unspoken Crisis: Mounting Textile Waste in China". Collective Responsibility. Retrieved November 10 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ "What does 潮人恐惧症 mean". 网络流行语.com. Retrieved November 9 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "What kind of "disease" is "fashion phobia"?". sohu.com. Feburary 3 2022. Retrieved November 10 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ Liying, Sun (June 3 2021). "Numbers Talk: People Trapped in "Appearance Anxiety"". Xinhuanet.com. Retrieved http://www.xinhuanet.com/video/sjxw/2021-06/03/c_1211184722.htm. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ Gu, Yingjie (May 27 2020). "This is China: The rise of 'China-Chic'". CGTN. Retrieved November 10 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ "Exploring China chic with young artists". BBC StoryWorks. Retrieved November 10 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Zipser, Daniel (December 14 2018). [The real reason why Chinese consumers prefer local brands "The real reason why Chinese consumers prefer local brands"] Check

|url=value (help). McKinsey&Company. Retrieved November 10 2022. Check date values in:|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ Woo, Ryan (March 25 2021). "Nike, Adidas join brands feeling Chinese social media heat over Xinjiang". Reuters. Retrieved November 10 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ Wu, Coco (August 24 2020). "Embracing the emergence of new 'China chic'". Campaign Asia. Retrieved November 10 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ "Scholarism". Duke Trinity College of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- ↑ Wong, Benson Wai-Kwok; Chung, Sanho (Summer 2016). "Scholarism and Hong Kong Federation of Students: Comparative Analysis of Their Developments after the Umbrella Movement" (PDF). Contemporary Chinese Political Economy and Strategic Relations. National Sun Yat-sen University. 2 (2): 865–884. line feed character in

|title=at position 49 (help) - ↑ Vines, Stephen (2021). Defying the Dragon: Hong Kong and the World's Largest Dictatorship. Oxford University Press. ISBN 10: 1787384551 Check

|isbn=value: invalid character (help). - ↑ Henningsen, Lena (Dec 2011). "Coffee, Fast Food, and the Desire for Romantic Love in Contemporary China: Branding and Marketing Trends in Popular Chinese-Language Literature". The Journal of Transcultural Studies. Vol. 2, no. 2: pp. 232 – 270. doi:10.11588/ts.2011.2.9089 – via DOAJ.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- ↑ Cai, Shenshen (2017). Contemporary Chinese Films and Celebrity Directors. pp. 155–160. ISBN -98-1102965-2, 978--98-1102965-3 Check

|isbn=value: invalid character (help). - ↑ Tsui, Christine (July 2019). "The Design Theory of Contemporary "Chinese" Fashion". Design issues. Volume: 35 Issue: 3: pp. 64-75. doi:10.1162/desi_a_00550 – via Art Full Text (H.W. Wilson).CS1 maint: extra text (link)

| This resource was created by Daniel Louie, David Yu, Michelle Yung, Mimi Shu. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |