Course:ARST573/Archives and Copyright

Copyright law and archives have a goal in common: to make cultural heritage material available in the long-term interest of society.[2]

Copyright law presents archivists with numerous challenges. Copyright has legal, financial, and cultural implications for both an archives and the public it serves. Balancing the rights of users, the rights of donors and creators, and the mandate of an archives is an ongoing effort in ethical assessment and risk management.[3] This wiki describes how copyright law, primarily the Canadian Copyright Act, either enables or prevents access to and distribution of archival material with a focus on the public domain, exceptions for archives, orphan works, digitization for access, and Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property.

Background

Definition

Copyright is the "exclusive legal right to reproduce, publish, sell, or distribute the matter and form of something (as a literary, musical, or artistic work)."[4] Copyright law seeks to balance the rights of creators to profit from their work with the creative health of society and the freedom to build on the work of another. Copyright is one of six types of intellectual property. The other types of intellectual property recognized in Canada are patents, trademarks, industrial designs, confidential information and trade secrets, and integrated circuit topography protection.[5] Copyright is a complex law that has evolved over time as lobbyists, including archivists, demand rights and new creative and reproductive media and technology shape the creative and intellectual landscape.

In Canada, copyright subsists in a work automatically if it meets the following basic criteria: the work is original and it is fixed in material form.[6] Compared to other countries, Canada has a low threshold for copyright to subsist in a work.[7] The owner of copyright is the creator of the work, but copyright may be signed over to another person or body.

International Protection

Copyright treaties have been adopted internationally to ensure that creators retain control over how their work is copied and distributed in another country. International copyright treaties provide copyright protection in one country, according to that country's copyright law, to nationals whose country has signed the treaty.

International Copyright Agreements

Berne Convention

Universal Copyright Convention

World Intellectual Property Organization Copyright Treaty

Brief History

The first copyright law was the Statute of Anne, which came into effect in Great Britain April 10, 1710. The first Canadian Copyright Act, modeled on the United Kingdom Copyright Act of 1911, came into force January 1, 1924.[8] Exceptions for libraries, archives, and museums were first introduced to the Act on April 25, 1997.[9] In November 2012, the Copyright Modernization Act came into effect. Amendments made to the Act provide a broader scope of exceptions for libraries, archives, and museums. Most notably, archives can now make digital copies for preservation purposes with certain exceptions and the responsibility for fair dealing of a work copied for a patron has shifted from the archives to the patron.

Copyright Bodies in Canada

Canadian Copyright Office (under the Canadian Intellectual Property Office)

Copyright Board of Canada

Works in the Archives

In the archives, copyright subsists in a "wide range of original works, including books, films, diaries, music letters, sound recordings, photos, and a host of other items"[10] both analog and digital including websites, emails, and databases.[11] Copyright law in Canada may or may not apply depending on the creator(s) of a record and if they are known, the type of record, and the way in which a record is used by an individual.

An archives may or may not hold copyright for works in its care. If the archives does not hold copyright, the person who wishes to copy a record may seek out the copyright owner to obtain permission. If possible, an archives may "attempt to obtain an assignment of copyright when documents are deposited in the archives. Where this happens, the archives will own the copyright."[12] Yet, a donor may not own copyright for all or any of the works they are donating to the archives and cannot assign it to the archives. Further, an archives may manage copyright on behalf on an institution who keeps its records.[13] For example, a university archives may administer copyright for all records created by the university.

Duration of Copyright and the Public Domain

Prior to the 1997 amendments to the Canadian Copyright Act, unpublished works were under copyright either until they were published, where copyright would then take effect, or in perpetuity if they remained unpublished[14] Lesley Ellen Harris explains that "the purpose of perpetual copyright protection in unexploited works was to protect authors and copyright owners from derogations of their private rights. For instance, there may be a desire not to publish certain letters, diaries, sketches and manuscripts. It was believed that if perpetual copyright did not exist, that some authors would destroy their works rather than have them ever fall into the public domain."[15] Perpetual copyright for unpublished works frustrated researchers in the archives. Although they were free to access the works for their research they could not reproduce or publish them.[16] Copyright law was amended to make it easier for researchers to publish previously unpublished works, and now both published and unpublished works are under copyright for the same duration.[17]

Works that have never been or are no longer protected by copyright are in the public domain. Copyright law covers "original" works, yet the definition of an original work varies from country to country. According to the Supreme Court of Canada's interpretation of the phrase "original work," "it is entirely possible that archival holdings consisting of facts recorded on standard forms (such as baptismal registers, land records, and the like) are automatically in the public domain."[18] Further, depending on the country, government records may or may not be in the public domain. For example, in the United States most government records are in the public domain whereas in Canada, some may be protected by Crown Copyright. Crown copyright protects Crown works of "federal, provincial and territorial governments" but usually not municipal governments.[19]

It is the fate of all works under copyright to eventually enter the public domain and be freely available to copy, digitize, and distribute. Fortunately, due to the age of the records, archives often contain works that are in the public domain, which is the salvation of archivists and users alike. The time when a work enters the public domain depends on whether or not the creator of the work is known. The Canadian Copyright Act states that copyright lasts for "the life of the author, the remainder of the calendar year in which the author dies, and a period of fifty years following the end of that calendar year."[21] If a creator is not well known and is not easy to track down, the date of death may be difficult to determine.[22]

The duration of copyright becomes complicated when the creator of a work is unknown. If the author of a work in unknown in Canada, the duration of copyright lasts either seventy-five years after the creation of the work or fifty years after the publication of the work, whichever ends first.[23] Since much archival material is unpublished, the former usually applies. If an archivist or a user wishes to copy a work under copyright for which the creator is unknown, they are faced with the challenge of orphan works.

Exceptions for Archives

Copyright law often provides exceptions for non-profit educational institutions, libraries, museums, and archives to provide greater access to the records and to promote learning and creativity.[24] The Canadian Copyright Act contains Sections that provide exceptions for archives that fall under two main categories: Fair Dealing, and Preservation Copies and Technological Obsolescence.

Fair Dealing

The Canadian Copyright Act states that "fair dealing for the purpose of research, private study, education, parody or satire does not infringe copyright."[25] Under Canadian copyright law, an archivist can provide a digital or analog copy of a record to a user if they intend to use it under the fair dealing provision. Unless it is in a closed system, it is likely that "making content of any sort available on the Internet would not fall within fair dealing"[26] because it would be viewable by the public. Fair dealing is a grey area of copyright law that requires careful interpretation.

Previously, archivists were under the legal obligation to ensure that users were making fair use of the records they copied. The onus has now shifted from archivists to users, who are responsible for determining whether or not use is fair. The archives still has a role to play in the process, as they must inform the user "that the copy is to be used solely for research or private study and that any use of the copy for a purpose other than research or private study may require the authorization of the copyright owner of the work in question.[27] Archives must inform users of fair dealing restrictions by posting notices in the reading room, stamping a paper copy with a copyright notice, or including a notice in a transparent overlay when scanning and providing a digital copy of a record. For example, the Simon Fraser University Archives' Copyright Notice explains to users,

- "that any copy is to be used solely for the purpose of research or private study; and

- that any use of a copy for a purpose other than research or private study may require the authorization of the copyright owner of the work in question."[28]

Preservation Copies and Technological Obsolescence

Records under copyright that are deteriorating or are recorded on obsolete media may need to be copied for preservation purposes. Recently, Canadian archivists lobbied the government to make changes to the Act to enable records to be legally copied for preservation purposes. In March, 2012, Nancy Marrelli, former archivist and Special Advisor, Copyright, for the Canadian Council of Archives, told the House of Commons that archives should have the right to legally circumvent TPMs (technological protection measures) for preservation purposes.[29]

The "Copyright Modernization Act" expanded provisions in order to accommodate copying for preservation purposes and technological obsolescence. The Act states that an archive may make a preservation copy from its permanent holdings, subject to certain conditions such as the rarity of the item and its physical condition.[30] Additionally, a copy may be made if "the original is currently in a format that is obsolete or is becoming obsolete."[31] These provisions enable archivists to create an analog or digital preservation copy or migrate material from an obsolete technology, yet they do not enable these items to be made publicly available online.

Challenges

Orphan Works

An orphan work is "a copyright-protected work, the rights owners of which cannot be identified or located by anyone who wants to make use of the work in a manner that requires the rights owner's consent."[32] Since material in an archives may not have been created by the creator of a fonds, orphan works may inhabit archives in large numbers. It is often more difficult to determine the copyright owner of photographic material and film than textual records, gray literature, and published works, which often provide more evidence of the creator. A work may be orphaned for any of the following reasons:

- the copyright owner is unknown or unlocatable

- copyright was transfered from the original owner to another unknown or unlocatable party.[33]

Orphan works become complicated when there are "numerous rights owners [who] might need to be traced."[34] Jean Dryden, an archival scholar and theorist, writes that "unless the records documenting such agreements [the transfer of copyright from one party to another] are also deposited in the archives, the archivist may be completely unaware of their existence, and will not know the identity of the current owners of particular copyright interests."[35] If an archivist encounters orphan works and wishes to either copy or provide public access to them, the archivist must put in a "reasonable effort" to locate the copyright holder. Dryden writes that "even if it is possible to identify the copyright owner, locating the copyright owner (or the owner's heirs) may not be easy."[36]

Once contacted, an assumed copyright owner has the right to either give or deny permission. Sometimes, a contacted person believes s/he holds copyright but in fact is not the legitimate copyright owner.[37] The effort and cost required to track down unknown copyright holders is a significant impediment and strain on resources. If an archivist has put in "reasonable effort" to determine and locate the copyright owner(s), the archivist must either take a risk and make the content available or deny "culturally and scientifically valuable content being used as building blocks for new works."[38] Orphan works challenge archivists to balance resources needed to track down suspected copyright holders and to practice risk management when they decide how to proceed with an orphan work.

Licensing

For orphan works in Canada, "the Canadian Copyright Board must be satisfied that the applicant has made 'reasonable efforts' to find the copyright owner before a license is issued"[39] and an archivist must prove that s/he has "conducted a 'thorough search.'"[40] However, the Copyright Board of Canada can only issue a license if the work has been published, which does not cover many archival records. The definitions of "reasonable effort" and "thorough search" are both open to interpretation. Copyright law provides strict regulations, yet much of the terminology remains unclear until it has been tested in a court of law.

Legislation

Currently, Canada does not have an orphan works provision for archives in its copyright law. Speaking to the House of Commons, Marrelli explains the difficulties presented by orphan works,

"archives expend scarce resources to acquire, preserve, and make our holdings accessible, but we often cannot use modern electronic communications means ... to make them available to the Canadian public because the copyright owners are unknown or cannot be located. They are orphan works. These orphan works fall by the wayside on the information highway of the 21st century. Important chunks of the Canadian experience fall into a black hole where access is severely limited." [41]

The lack of an exception in the law for orphan works affects which records archives decide to make available to the public, whether in an exhibition or online.[42] The decision is an effort in risk assessment. An archives has to decide if the cost required to track down potential copyright holders of orphan works is realistic, if they will not include orphan works, or if they will take a risk and display the records.

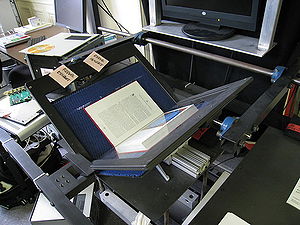

Digitization for Access

Digital distribution makes it easier for archivists and users to copy and distribute archival records. The digitization of archival holdings has pushed copyright to the forefront in many archives. When an archives undertakes a project to digitize records for public access, copyright is the first factor that must be considered. For example, orphan works become especially troublesome when archives undertake mass-digitization projects. If works are covered by copyright, they cannot be digitized for public access.[44] Additionally, the quest to determine ownership of orphan works may pose a significant barrier to archivists and either stall or halt a project. One study of Canadian archivists found that in order to avoid complications posed by copyright, archivists digitize fewer holdings than necessary.[45] In her study, Dryden found that archivists err on the side of caution and "prefer to select documents [for digitization] that are perceived to incur little risk of copyright infringement, those that require minimal effort to clear copyrights, or both."[46]

With regards to copyright, archivists express the following concerns when they make records available online

- the records will be used to generate profit

- the authenticity of the records will be compromised

- the reputation of the archives will be affected negatively

- the archives will be at risk of legal liability.[47]

In another study, Dryden found that archivists are at times guilty of "copyfraud," which is false claims of copyright.[48] While digitization enables access, it also increases the risk of liability. To inform users of copyright restrictions, descriptive metadata for archival records online now often includes the copyright status of an item.

Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property

Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) may include photographs, stories, oral histories, films, and genealogical information[49] belonging to Indigenous people. Terry Janke, an Australian Intellectual Property Lawyer, argues that intellectual property laws "allow for the plundering of Indigenous knowledge by providing monopoly property rights to those who record or write down knowledge in a material form."[50] Over time, ICIP has been gathered and recorded "at a time in history when Indigenous people could not exercise their prior and informed consent."[51] The copyright may have expired or may belong to the individual who recorded the material, yet the traditional knowledge in the record belongs to Indigenous people and "the uses that are now being made of this are often not in accordance with the original intention."[52]

Copyright law may "not cover all the types of rights Indigenous people want for their ICIP."[53] Copyright does not cover "intangible expressions of cultural heritage" such as "ritual or spiritual properties that objects or archival records embody."[54] For example, an ethnographic recording of an oral story housed in an archives has two dimensions that require two different types of legal ownership: the fixed record, which may be under copyright, and the traditional knowledge it contains, which itself is not protected by copyright.[55] Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada's working paper on intellectual property explains, "as copyright protects the expressions of ideas and not the ideas themselves, it would be difficult to obtain protection for traditional knowledge or legends which are not 'fixed' in writing, film or art but are passed down orally from generation to generation."[56] For example, an anthropologist who recorded an oral story may hold copyright for the recording. However, the Aboriginal community who owns the cultural property will not have the ability to control how the traditional knowledge is used.

Another shortcoming of copyright law from the perspective of ICIP is that it "does not allow legends and stories belonging to a community to be protected in perpetuity."[57] Often, the duration of copyright is seen by some as too long, but it may be too short for those who want control over their traditional knowledge and cultural property. For example, "many Aboriginal works were created generations ago and transmitted orally. Under current copyright law, they may be considered to be in the public domain and therefore open for use by outsiders without the Aboriginal community's consent."[58]

Cultural Copyright

The term cultural copyright is used to recognize an Indigenous community's moral rights to their cultural property even though they may not possess the legal rights to it. Currently, Canadian copyright law does not protect traditional knowledge and cultural property that is not in a fixed form.[59] Michael Ames explains that "'cultural copyright'" or creative control should be recognized even though the photographer, film-maker, or archives may have legal possession of the images"[60] or records in their care.

One possible solution for the management of digital records is Mukurtu. Mukurtu is a free, open source software program that enables indigenous communities to share their digital heritage and manage its distribution according to their own cultural systems. It was developed in Australia and is used by communities internationally.

Role of the Archivist

Archivists in Canada have not been absent from the debate on copyright and have been openly critical about copyright law and lobbied the government for changes so that they may preserve records that are threatened by technological obsolescence and provide greater access to their collections. In order to protect the archives from liability, archivists must be aware of laws that affect how records under their care are made available and accessed, yet this is not an easy task. Archivists are caught between users, who increasingly request unlimited access to and the right to copy and distribute records, and the rights of creators, which may restrict use. In order to understand the grey areas of copyright law, it is necessary to see how specific court cases have interpreted the law and to establish best practices in the archival community.[62]

Archivists whose holdings contain ICIP must balance several factors when they decide how they will provide access to and reproduce ICIP. Archivists must consider copyright law and their professional ethics and standards. A report called Turning the Page: Foraging New Partnerships Between Museums and First Peoples recommends that professionals build relationships with Aboriginal people in order to better understand how to respect their ICIP. These "new partnerships should be guided by moral, ethical and professional principles, and not limited to areas of rights and interests specific by law."[63]

Although archives often work hard to strictly observe copyright law, they may need to take a different approach that extends beyond the law. Archivists also need to consider how cultural copyright and privacy restrictions on material may conflict with their mandate and professional ethical codes, which promote access and use of the records. Rather than accept copyright law at face value and apply it indiscriminately to all material, cultural heritage professionals need to be aware of ICIP considerations and manage them appropriately.[64]

Jean Dryden offers recommendations for the improvement of archivists' copyright knowledge such as the creation of continuing education programs and up-to-date guidelines as well as access to a copyright expert.[65] If archivists and others concerned continue to lobby the government for copyright reforms and greater protection for the use of orphan works and for the protection for ICIP, copyright law will continue to evolve to reflect their needs as it has in the past.

Resources

The following freely accessible guidelines and reports are a sample of online resources that guide both archivists and the public on copyright legislation and policy in Canada and internationally:

Canada

Balanced Copyright (Government of Canada)

Copyright Information for Archives and Archivists

Copyright Guidelines for Researchers at the City of Toronto Archives

International

Copyrightlaws website

IASA (International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives) Archives and Copyright Owners

IFLA (International Federation of Library Associations) Copyright Limitations and Exceptions for Libraries and Archives

WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organization) Standing Committee on Copyright and Related Rights: Study on Copyright Limitations and Exceptions for Libraries and Archives

Digital Records

Copyright and Cultural Institutions: Guidelines for Digitization for U.S. Libraries, Archives, and Museums

Copyright Issues Relevant to the Creation of a Digital Archive: A Preliminary Assessment

International Study on the Impact of Copyright Law on Digital Preservation

See also

Archives and Power

Ethics and Archives

First Nations Archives

Literary Archives

Notes

- ↑ Unknown. "Copyright." Photograph. Retrieved April 11, 2013 from http://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Copyright.svg&page=1 Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

- ↑ Dryden, Jean Elizabeth. "Copyright Issues in the Selection of Archival Material for Internet Access." Archival Science 8 (2008): 124, doi: 10.1007/s10502-009-9084-3.

- ↑ Ibid., 126.

- ↑ Copyright. (n.d.). In Merriam Webster online. Retrieved from http://www.merriam-webster.com/

- ↑ Harris, Lesley Ellen, Canadian Copyright Law: The Indispensable Guide for Publishers, Web Professionals, Writers, Artists, Filmmakers, Teachers, Librarians, Archivists, Curators, Lawyers and Business People 3rd ed. (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 2001): 2.

- ↑ Ibid., 17.

- ↑ Ibid., 19.

- ↑ Ibid., 12.

- ↑ Ibid., 13-14.

- ↑ Copyright Guidelines for Researchers. (n.d.). City of Toronto http://www.toronto.ca/archives/copyright.htm

- ↑ Harris, Canadian Copyright Law, 59-75.

- ↑ Dryden, Jean E. "Is that Copyright Too Strong? Copyright in Archival Material," Journal of Canadian Studies, 40 no.2 (2006): 170. doi: 10.1353/jcs.2007.0014.

- ↑ Ibid., 170.

- ↑ Harris, Canadian Copyright Law, 97.

- ↑ Ibid., 97.

- ↑ Ibid., 97.

- ↑ Ibid., 97.

- ↑ Dryden, "Copyright Issues," 124, doi: 10.1007/s10502-009-9084-3

- ↑ Harris, Canadian Copyright Law, 73.

- ↑ Unknown. ["Family in traditional clothing in front of Wah Chong Washing and Ironing."] Photograph. ca.1895. Retrieved April 11, 2013 from City of Vancouver Archives http://searcharchives.vancouver.ca/family-in-traditional-clothing-in-front-of-wah-chong-washing-and-ironing;rad Public domain.

- ↑ Canadian Copyright Act 1985, c.C-42, Section 6, http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-42/index.html

- ↑ Dryden, "Is that Copyright Too Strong," 170.

- ↑ Canadian Copyright Act, Section 6.1, http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-42/index.html

- ↑ Harris, Canadian Copyright Law, 144.

- ↑ Canadian Copyright Act, Section 29, http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-42/index.html

- ↑ Dryden, "Copyright Issues," 125, doi: 10.1007/s10502-009-9084-3

- ↑ Canadian Copyright Act, Section 30.2, http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-42/index.html

- ↑ Vice President, Legal Affairs, "Copyright Notice," Simon Fraser University Archives, last revised March 9, 2012.

- ↑ Canada, Parliament, House of Commons, Legislative Committee on Bill C-11, 1st Session, 48th Parliament, 1 March, 2012, (Ms. Nancy Marrelli), http://www.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?DocId=5415862&Language=E

- ↑ Canadian Copyright Act, Section 30.1, http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-42/index.html

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Gompel, Stef van and P. Bernt Hugenholtz. "The Orphan Works Problem: The Copyright Conundrum of Digitizing Large-Scale Audiovisual Archives, and How to Solve It." Popular Communication: The International Journal of Media and Culture 8 no.1 (2010), 63, doi: 10.1080/15405700903502361

- ↑ Dryden, "Copyright Issues," 125, doi: 10.1007/s10502-009-9084-3

- ↑ Gompel and Hugenholtz, "The Orphan Works Problem," 62, doi: 10.1080/15405700903502361

- ↑ Dryden, "Copyright Issues," 125, doi: 10.1007/s10502-009-9084-3

- ↑ Ibid., 125.

- ↑ Dryden, "Copyright Issues," 137, doi: 10.1007/s10502-009-9084-3

- ↑ Gompel and Hugenholtz, "The Orphan Works Problem," 62, 10.1007/s10502-009-9084-3

- ↑ Ibid., 67.

- ↑ Ibid., 67.

- ↑ Canada, Parliament, House of Commons, Legislative Committee on Bill C-11, (Ms. Nancy Marrelli), http://www.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?DocId=5415862&Language=E

- ↑ Dryden, "Copyright Issues," 123, doi: 10.1007/s10502-009-9084-3.

- ↑ Dvortygirl, photographer. "Internet Archive Book Scanner." Photograph. 23 February, 2008. Retrieved Aprill 11, 2013 from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Internet_Archive_book_scanner_1.jpg Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

- ↑ Padfield, Tim. Copyright for Archivists, 2nd ed., (London: Facet Publishing, 2004), 12.

- ↑ Dryden, "Copyright Issues," 123, doi: 10.1007/s10502-009-9084-3

- ↑ Ibid., 136.

- ↑ Dryden, Jean Elizabeth. "Copyfraud or Legitimate Concerns? Controlling Further Uses of Online Archival Holdings." The American Archivist 74 (2011), 528.

- ↑ Ibid., 523.

- ↑ Janke, Terri. "Managing Indigenous Knowledge and Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property." Archival Indigenous Knowledge and Libraries 36 no.2 (2005), 99.

- ↑ Ibid., 100.

- ↑ Ibid., 101.

- ↑ Ibid., 101.

- ↑ Ibid., 100.

- ↑ Laszlo, Krisztina, "Ethnographic Archival Records and Cultural Property," Archivaria 61 (2006), 300-301.

- ↑ Ibid., 301-302.

- ↑ Canada, Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development and Industry Canada, "Intellectual Property and Aboriginal People: A Working Paper" (Ottawa, 1999): 14 http://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/tk/en/folklore/creative_heritage/docs/ip_aboriginal_people.pdf

- ↑ Ibid., 14.

- ↑ Ibid., 15.

- ↑ Harris, Canadian Copyright Law, 73.

- ↑ Ames in Laszlo, "Ethnographic Archival Records," 301.

- ↑ "This is Mukurtu," YouTube video, 2:58, posted by "mukurtu," September 30, 2011, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rsk_j7kPlz0

- ↑ Harris, Canadian Copyright Law, xiii.

- ↑ Laszlo, "Ethnographic Archival Records," 303.

- ↑ Janke, "Managing Indigenous Knowledge."

- ↑ Dryden, Jean Elizabeth. "What Canadian Archivists Know About Copyright and Where They Get Their Knowledge." Archivaria 69 (2010), 115.