Course:ARST573/Archives in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is comprised of 11 nations: Brunei, Cambodia, East Timor, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. [1] With the exception of East Timor, all are members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)[2] which was formally established in 1967 for purposes of economic cohesion, regional peace, collaboration and assistance, and the promotion of Southeast Asian studies.[3]

While homogenization can be useful for identifying commonalities, it poses a number of challenges.[4] The term "Southeast Asia" is inherently limiting, if only because it promotes generalizations of the area and its inhabitants.[5] While several countries uphold similar religious views and traditions, the majority of nations included are more dissimilar than they are alike, especially when considering the implications of geography, colonization, language, memory, culture and politics ;[5] in fact, "[t]he ethnic mosaic of Southeast Asia is a result of the emergence of local differences between people that have evolved into identifiable cultural or ethnic groups."[6] It is important to acknowledge Western preoccupations with homogeneity and unity when attempting to describe a region that is arguably "heterogenous, disunited, and hard to delimit."[5] For example, 8 of the 11 member states have established independent national archives, though only two (Malaysia and Singapore) have formulated digital preservation strategies.[7][8] Several countries, namely Myanmar and Cambodia, witnessed uniquely pronounced cultural and political upheaval over the turn of the (21st) century which has prompted increased attention to accountability and preservation of their national identities.[9][10][11] Furthermore, Thailand is the only Southeast Asian country that was never (legally) colonised.[12][13] Although the ASEAN agreement has helped foster a sense of regional spirit and community that might not otherwise have been possible,[3] it is also helpful to approach archival work in the region as a collaborative web versus a "one size fits all" delineation.

National Archives of Cambodia

Established under French colonial rule in 1863, The National Archives of Cambodia (NAC) formally became a centralized repository in 1926 following a series of regulations related to the classification and administration of government archives as well as to archivist recruitment and training in French Indochina (including Vietnam and Laos).[14] From its inception until Cambodian independence in 1954, NAC and the National Library were administered together and reported to the Governor General of Indochina in Hanoi.[14] Following independence, however, archival administration was relegated to the Cambodian government(s) which between 1953 and 1975 "continued to transfer documents to the National Archives for long-term preservation, although with sharply decreasing regularity."[14] Accordingly, government ministries were in possession of a signification portion of Cambodia's documentary heritage during the Khmer Rouge's ascension to power in 1975.[14]

Impact of the Khmer Rouge (1975-79)

See also Archives and Genocide, Archives and Repressive Regimes

Between 1975 and 1979 the Khmer Rouge wreaked havoc on the Khmer people and nation: over one million citizens perished during its reign.[14][15] While the NAC building in Phnom Penh remained intact, records suffered unduly from neglect: "Records were pushed from the shelves to make way for cooking implements and food. Records were strewn around the building, and some of them were used to light fires."[14] Surprisingly, in spite of the regime's unwonted disregard, most of the NAC's holdings remained in tact.[14] However, the card catalogue--which allowed for intellectual control over the holdings--did not.[14] The regime was disposed of in 1979, preceding decades of painstaking conservation and ongoing archival efforts towards truth and accountability.[14][15]

Records have been extremely influential in the lawful exposure of the Khmer Rouge's atrocities as well as its major perpetrators.[16] The Vietnamese army which invaded Cambodia and upset the regime in 1979 "encountered troves of documents at Tuol Sleng [Khmer Rouge prison in Phnom Penh] and other Khmer Rouge offices and recognized the importance of these records [...] to hold the regime accountable."[17] As such, using recovered records as legal evidence, many Khmer Rouge leaders were convicted for war crimes; "the preservation of documents and artifacts at Tuol Sleng began almost immediately after the fall of the Khmer Rouge and has been inextricably linked to international politics from the start."[17] The prison has since been converted into a 'Genocide Museum', with its archives being accessible to local and foreign scholars since the 1980s.[17]

Materials

The NAC archival holdings include: HCA Elmiger photography collection (rubber plantations); textual records of the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (1992-95); film and audiovisual archives; maps and plans; posters (1954-1993); textual records of the Genocide Tribunal of 1979 (e.g., survivor testimonies).[18][19]

Mission

As a public institution, the NAC professes to be "responsible for preserving documents created by the Government of Cambodia, which possess enduring legal and historic value, and for making them available for present and future generations to use."[20] The NAC is committed to public outreach and consciousness raising of the importance of archives, particularly given its troubled history and persistent reliance on archives for truth, justice and accountability.[20][15] The NAC welcomes local and foreign scholars, students, and members of the general public to utilize its holdings for purposes of research or discovery.[20]

National Archives of the Republic of Indonesia

Responsible only to the President of Indonesia[21], The National Archives of Indonesia (ANRI) is a non-governmental institution legally established by the Indonesian government in 1971.[21] Accordingly, ANRI specifies archival materials as "all records produced or received by functionaries acting as agents of the government or governments which were generally recognized as the legitimate rules of what at present is known as Indonesian territory, or portions thereof [...] and should therefore be preserved in a repository authorized as such by our government."[22] Referring primarily to the writings and practices of Dutch archivists, ANRI acknowledges the archival contributions of the Netherlands as assisting in the formation of its core archival collection.[23]

Materials

ANRI houses records from the late 16th century to the present day in accordance with ANRI's commitment to the preservation and continuation of its collective memory and national heritage, including a plethora of documents related to 19th century European colonial relations in the archipelago.[21][24]

Mission

ANRI's archival mission encompasses:[21]

- Strengthening the archives as the foundation of good governance and developmental management

- Strengthening the archives as a performance accountability apparatus

- Strengthening the archives as legal evidence

- Preserving the archives as collective memory, national identity and evidence of national accountability

- Providing and promoting public access to the archives to cultivate government and civic interests

Challenges

Recurrent challenges ANRI faces include: dislocation of public papers due to death or retirement of public officials, colonization, or war; a relatively high frequency of cabinet changes; departmental unfamiliarity with ANRI's authority over public records.[25]

National Archives of Malaysia

Existing as the singular repository for research materials in the country, the National Archives of Malaysia was founded in 1957.[26] The National Archives Act of 1966 specifies that the National Archives is responsible for the acquisition and preservation of all public, private, and business archives.[26] Initially a subset of the National Archives, the National Library of Malaysia (NLM) became an independent institution in 1977 which, under the Deposit of Library Material Act 1986, requires all Malay publishers to deposit five copies of printed materials and two copies of un-printed materials in the NLM for future reference and research.[27] In 2003, the government passed the National Archives Act which authorizes the National Archivist to appraise all public records, including those in electronic form, prior to their destruction to ascertain their long-term, archival value.[28]

Materials

Materials in the National Archives date from 1700 to the present day and include "files, papers, documents, registers, printed materials, maps, plans, drawings, photographs, microfilm and cinematograph films of any kind whatsoever accumulated by a government office."[29] The National Archives Act specifies "public records" as those "officially received or produced by any public office for the conduct of its affairs or by any public officer or employee of a public office in the course of his official duties and includes the records of any Government enterprise [...]."[30] Private archives pertain to those records acquired from prominent historical figures who have been or are intricate to the development of the nation.[31] Additionally, the National Archives produces an annual report which details its yearly accessions and can be purchased for a modest sum.[31]

Mission

The official objectives of the archives include:[32]

- Raising the standard of records management in the public sector via advisory service and formulation of the National Archives Act 2003

- Heightening civil awareness of the need to preserve institutional memory via the preservation of valuable public records

- Acquisition of archival materials through various types of donation

- Preserving archival materials as documentation of Malaysia's national heritage

- Providing access to the archives as relevant reference and research sources

- Strengthening awareness and appreciation of Malay history via the use and understanding of archival holdings

- Promoting the utility of archival materials via exhibitions, publications and technology

- Promoting the visibility of the National Archives via public outreach

National Archives of Myanmar

See also Archives and Repressive Regimes

As a recently democratized nation, Myanmar (formerly Burma) is steadily formulating its archival mission and priorities.[33] Myanmar was under military control and censorship between 1962 and 2010; during this time, a National Archives Department (NAD) had been established under the Ministry of National Planning and Finance in 1972, though it was considered a "third grade Department" with little authority.[34] As such, it was necessary for an external impetus to prompt initiatives to strengthen the Department, which arrived in the form of UNESCO assistance in 1982.[33] In 1990, the National Records and Archives law upgraded the NAD as a second tier Department and was relocated to its current positioning under the Ministry of National Planning and Economic Development.[34] Finally, following further structural reorganization and an amendment to the 1990 law, NAD was deemed a "first grade" Department on January 12, 2012.[34]

Prior to 2011-12 political reforms, Myanmar held to strict censorship rules regulating freedom of the press, many of which were carried over from its colonial administration.[35] As a result, scholarly publications were restricted to "safe topics" (e.g., history, religion, art, music, archeology).[35] In 1999, approximately 227 book titles and "less than 10 scientific and technical journal articles per million people (the total population is about 43 million)" had been published in Myanmar.[35] While some Myanmar scholars were able to publish their work abroad, "in the periphery of the country there [were] isolated and thriving publishing industries that operate[d] outside of the central government's control."[35] In remote areas some ethnic groups "formed independent cultural and literary commissions to publish alternative histories" and political opposition groups distributed publications, "reflect[ing] a relatively weak military and political control over its remote areas by the [former] Myanmar government."[35]

UNESCO Aid (1982)

Concerned by the conditions of Myanmar's national archival holdings, UNESCO prepared a detailed report, outlining relevant priorities for the developing nation to consider as it began to strengthen its archival program. A major consideration was the status of its microfilm holdings which lacked both means of intellectual control (e.g., indexing, archival description) and effective environmental controls (e.g., thermo-hygrograph).[33] The report specifies recommendations for both preservation and cataloguing techniques to supplement and thus strengthen the longevity of its diverse collections.[33]

Materials

The National Archives of Myanmar's holdings are divided into 29 record groups primarily based on ministerial creator.[36] Records date from 1824 ("Pre Independence") and encompass: World War II; Post Independence (1948-88); Revolutionary Council and Government (1962-74); State Council (1974-88); State Law and Order Restoration Council (1988-97); National Convention (1993-2006); State Peace and Development Council (1997-2010); The Republic of the Union of Myanmar (2011-present).[36] Record types of archival worth include printed (e.g., "official publications of various government institutions") and non-printed materials (e.g., microfilms, recorded tapes, photographs, motion picture film, CDs).[36]

As of 2014, the Archives has reduced public security access to its 1963 holdings; records from 1835-1963 are now open to local and foreign scholars.[37] Foreign scholars are able to utilize the holdings for a fee following written permission via the Myanmar Embassy in their country of origin.[38]

Mission

The National Archives of Myanmar delineates its objectives as:[39]

- Safe-keeping and conserving national records and archives in perpetuity

- Collecting and receiving accumulated records "which may be migrated or in the possession of individuals as well as certain organizations" for departmental safe-keeping "as a national cause"

- Collaborating at the international level with archival institutions to supplement its "knowledge of Records Management and Archives Administration"

- Extracting "important facts from the Archives and disseminat[ing] them among the Myanmar people" for purposes of archival "awareness and response," conducive "to realizing the political, economic and social objectives of the nation"

Additionally, the Archives strives to "become an outstanding National Centre for Archives and Archival Research" by means of heightened preservation, outreach and reference services.[39]

National Archives of the Philippines

Promulgated on December 10, 1898, the Treaty of Paris established the Office of Archives, providing for the "cession of documents from Spanish to American authorities and [...] for the preservation of documents whether they may be in Spain or in the Philippines."[40] A series of acts[41] followed the Treaty, including Commonwealth Act No. 2572 which stipulated the merging of the Division of Archives with the Philippine Library and Museum in 1916.[40] An Executive Order written in 1958 established the Bureau of Records Management, naming the Division of Archives as under its authority. Another series of interrelated acts and orders[40] followed, culminating with Republic Act No. 9470 in 2007, created to "[strengthen] the system of management and administration of archival records," including the formal establishment of the National Archives of the Philippines.[40]

Materials

Archival holdings within the National Archives cover a wide diversity of record type and subject matter; unpublished manuscripts and printed materials form the foundation of its holdings.[42] Available records range in date from the mid-16th century (during Spanish colonial rule) to modern day.[43] Notable materials include: "Insurgent records" from the Philippines revolutionary period (1898-1903); papers of former President Manuel L. Quezon (1907-1944); periodicals, pamphlets and books on Philippine medicine, science and history; Masters theses and dissertations on or about the Philippines; maps; photographs; microfilms; posters; musical scores.[42][43]

Mission

Committed to good governance, accountability and transparency, the National Archives of the Philippines strives to "promote freedom of information, provide access to official records, preserve and popularize Filipino cultural heritages, and strengthen national identities."[44] Furthermore, the National Archives promotes the importance of public outreach and international cooperation for the "effective implementation of programs on records management and archives administration."[44] Ongoing support for the National Archives is crucial for developing and maintaining a "vibrant, well informed, developed and open Filipino society."[44]

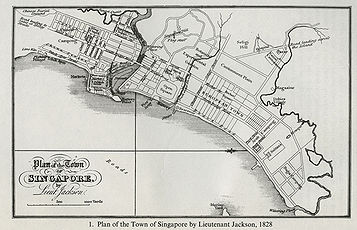

National Archives of Singapore

Though originally under direction of the National Library, the National Archives and Records Centre of Singapore was formally established as an independent institution in 1968 following the passage of the National Archives and Records Centre Act in September 1967.[45] In 1993 the National Archives merged with the Oral History Department to form the National Archives of Singapore (NAS), independent of the Records Centre.[46][47] However, as a result of governmental reorganization, NAS has been an institutional organization responsive to the National Library Board since March 2013.[47] In response to the rapid accumulation of its physical holdings and textual records, NAS supplemented its repository at the Ford Factory, the site of British surrender during World War II.[47]

Materials

NAS archival holdings comprise a diversity of record types, including: government textual records; photographs; architectural plans; audiovisual recordings; oral history interview transcripts; speeches; press releases.[48] NAS also features an online, searchable database, providing access to a notable selection of its current holdings and finding aids. Additionally, its location at the Ford Factory, now referred to as 'Memories at Old Ford Factory' (MOFF), engendered the curation of a special exhibition gallery featuring stills from WWII Occupation (1942-45).[47]

Mission

NAS outlines its archival mission as follows:[49]

- Advising public agencies on record management standards, including acting as the Official Keeper of records transferred by public departments

- Acquiring broadcasted or public audio visual recordings produced in Singapore

- Collecting oral history interviews

- Acquiring "any document, book or other material which is or is likely to be of national or historical significance"

- Promoting the importance of archives via publications, exhibitions and NAS-sponsored activities

Citizen Archivist Project

To assist with the development of its online database (Archives Online), NAS has instituted a Citizen Archivist Project whereby the public can choose to describe images (e.g., location, date, persons) or transcribe documents (e.g., tags, transcription of handwriting).[50] The purpose of the project is to help render NAS' holdings "more discoverable."[50]

National Archives of Thailand

Established in 1952 under the Department of Fine Arts, The National Archives of Thailand is divided into two sections: The Archives Section and the National Diary Section.[51] Around the time of its foundation, the Thai government sent a scholar to study archival science in the U.S.; she eventually returned to the National Archives in 1968 with newfound knowledge about the importance of research finding aids as well as conservation of textual records which have since been incorporated into the National Archives' practices.[51]

Information Act (1997)

Thailand has witnessed a number of military coups in its history as a nation. As such, there have been multiple instances of censorship and dissidence, resulting in the non-disclosure of political information and documents.[52] In 1997, the Information Act of Thailand was created and considers two primary objectives:[53]

- "To provide principles and mechanisms to protect [Thai citizens'] right to know," including flow of information from and civic engagement in the public administration

- "To provide principles and mechanisms to protect [...] privacy and personal information controlled or kept within state agencies or state enterprises"

The Act concerns the National Archives of Thailand as it explicitly describes circumstances in which citizens may or may not access governmental (i.e., public) records: "Information not automatically subject to release includes 'official information which may jeopardize the Royal Institution' and any information which 'the disclosure thereof will jeopardize the national security, international relations, or national economic or financial security.'"[52]

Materials

The National Archives of Thailand's holdings date from the reign of King Rama IV to the present day and include over one million historical, government and public records (e.g., textual records, photographs, posters, maps, video tapes, sound recordings). Foreign scholars are able to use the Archives' research services following permission by the Director-General of the Department of Fine Arts.[51]

According with the Prime Minister's Regulation on Records Keeping (1983), government records are transferred to the National Archives after 30 years from the date of creation.[54] Following transfer, archivists appraise records for long-term preservation based on historical value. Records can also be acquired by the Archives through private donation.[54]

Mission

In addition to serving as the main advisor to government agencies on records management and preservation, the National Archives of Thailand is responsible for collecting and preserving public records and historical materials of value and making them available to the public.[54]

National Archives of Vietnam

The National Archives of Vietnam has repositories throughout the country, though the primary repositories (I & II) are located in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City.[55][56] Although additional collections (e.g., Archives of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, provincial repositories) reside elsewhere in Vietnam, the National Archives' holdings are those "most readily accessible to overseas scholars" and comprise the majority of the nation's materials related to the social sciences and humanities.[55]

During Vietnam's period of French colonial rule, colonial authorities "mandated the archival retention of documents with permanent value" through the Direction des Archives et Bibliothèques (1917).[55] The 1917 decree provided for the establishment of the Office of Archives in Hanoi as well as the Vietnamese national script quoc ngu.[55]

Physical conditions of Vietnam's archival repositories remain some of the worst in Southeast Asia due to a variety of factors: "Vietnam's subordinate relationship to China for almost a millennium, and its later status as a French colonial territory, led to repeated periods of warfare and political instability. These factors, together with harsh climatic conditions, are responsible for the destruction of much of the nation's early historical and literary legacy."[55]

Imperial records

See also Archives and War

Imperial records were originally housed in the former capital of Hue, though in 1942 some records were transferred to the National Archives following a subsequent Direction des Archives.[55] For those which were not transferred, an estimated three-quarters of the court records were destroyed during the Viet Minh war (1946-54).[55] The National Archives, however, "still hold many manuscript records concerning land rights and usage, including village regulations and land-tax records showing boundaries drawn up by the imperial government."[55]

Materials

Holdings at the Archives include: colonial records of the Resident Supérieur du Tonkin; Nguyen dynastic records (e.g., local land and tax records); records of the Republic of Viet Nam.[56]

Foreign scholars are able to access the Archives following submission of a letter of recommendation and proof of an official research sponsor.[56]

Common Archival Considerations

Colonialism

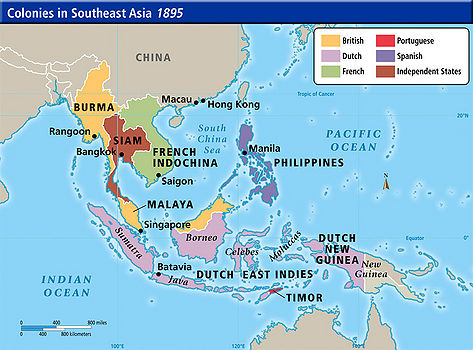

See also History of Southeast Asia: European colonization

For thousands of years Southeast Asia has been exposed to a multitude of civilizations, cultures and religions (e.g., animism, Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, Hinduism, and Islam).[13] Chinese and Indian dynasties largely influenced the formation of Southeast Asian societies and kingdoms: between the 12th and 14th centuries the two major kingdoms in Southeast Asia (Sukhotai in mainland Southeast Asia and the Majapahit empire in insular Southeast Asia) were commercially tied to East, South, and West Asia via an international spice trade.[13] Then, between 1500 and the mid-1940s, much of Southeast Asia came under colonial rule by European, American, and Asian powers for reasons of: territorial expansion, mercantilist profits, the importation of inexpensive raw materials, and the extraction of precious metals.[13]

The major colonial powers in Southeast Asia were:[13]

- Portugal: Indonesia (1511-1641); East Timor (1511-1975)

- Spain: Philippines (1565-1898)

- Dutch East India Company: Indonesia (1605-1799)

- The Netherlands: Indonesia (1825-1940s)

- Britain: Burma (1826-1935); Malaysia (1824-1957); Singapore (1819-1957)

- France: Cambodia; Laos; Vietnam (1859-1954)

- United States: Philippines (1898-1946)

- Japan: World War II (1940s)

While it has manifested in a variety of ways, Colonialism can be defined as "foreign political rule or control imposed on a people [or nation]."[13] In addition to political (e.g., territorial expansion) and economic motives, colonial powers were also driven by cultural values, including religious or racial superiority.[13] However, neither motivations nor effects were identical for all countries involved in the colonization of Southeast Asia: the Dutch were primarily encouraged by financial rewards from trade;[57][58] Spain and Portugal disseminated Catholicism;[13] British, French, American and Japanese colonial histories were influenced by imperialism ;[58][59] Burma was considered a province of British India, "unlike other colonies which kept their ethnic identities";[13] In Progress

Colonial powers inundated Southeast Asia with modern Western concepts, including: the printing press,[60] "the nation-state and its concomitant bureaucratic structure, education for ambitious youth in political theory and human rights, new economic opportunities and travails and new perspectives on religion."[61] Yet, it is similarly true that "[m]any societies outside Europe had developed an extensive oral and intangible heritage and advanced writing systems and preservation practices long before [...] colonists arrived with their own record-keeping systems, and with their European paper,"[62] Southeast Asia as no exception.

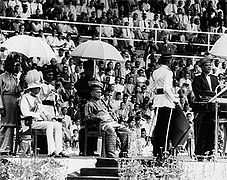

Following WWII, colonialism gradually conceded to nationalism as nations steadily gained independence from their colonial rulers:[13] newfound independence and freedom from imperialist influence "provided a new identification for the various countries of [Southeast Asia],"[6] as the decolonized states began strengthening existing political systems and social structures.

Postcolonialism

See also Postcolonial Archives

Scholarship on nationalism and postcolonialism reveals "that nationalist agendas contributed significantly to the production of collective memory as efforts to define the national community required a reconfiguration of multiple pasts into a single, dominant narrative," though this view has been problematized by localized autonomy movements throughout the region (e.g., southern Thailand/northern Malaysia, southern Philippines, northeast/southeast Burma, Indonesia).[63] The experience of "rapid urbanization or economic change" can incite "serious growing pains. [Intra-state c]onflicts usually erupt over control of resources and land ownership, ethnic groups usually vie for power, and environmental damage is usually extensive."[6] Furthermore, although cultural and economic relationships between former colonies and their counterparts remain, some countries (e.g., Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam) are taking longer to establish trade relationships with global markets due to the implications of 20th century strife and instability (e.g., Vietnam War, communism, military rule).[6] Demands of a competitive global economy necessitate reorganization of local markets, a process which requires considerable time and effort to effect change.[6] Priorities in these countries are based on immediacy and cost-efficiency, rendering substandard archival environments a major consequence.[55][64]

Colonial records

See also Archives and Repatriation, Postcolonial Archives

Archives can be defined "as objects in any form that record information which is preserved for future use as a memory aid."[65] Alternatively, colonial archives can be defined "as 'process bound information that flows from the constitution, maintenance, direction, management, exploitation and development of the territories and populations which have a relationship of administrative dependency on an external ruling power."[66] Therefore, textual records (e.g., maps, surveys, guidebooks, pamphlets) comprised as much of the "colonial project as [did] roads, policing, and taxation."[63] Colonial powers relied on records "not only to preserve the past but to prescribe the future," particularly as they relied on such records for policy formulation, legal precedence, and legitimization of its authority.[63][67]

Furthermore, because colonial documents were predominantly written and communicated by those in power, "[r]ecognizing that records may have misread, mislabeled, or misconstrued the societies they represented is but one level of critique -- we now accept, furthermore, that the very act of representation through documents and the objectification of culture is crucial to our critique of archival sources and the social contexts that produced them."[63] This view complicates archival attempts to describe colonial records for posterity, considering vested interests of the record's creator as well as the possibility of forgery, misrepresentation or third party interference.[68]

While some colonial documents can be found in Southeast Asian national repositories,[21][40] the majority of records are retained by the colonial administration that created them.[66] In recent decades, colonial records have been steadily released by administrations (e.g., the National Archives in London, archives in the U.S. on Laos) for purposes of transparency, as well as to settle border disputes or promote the cultural heritage of former colonies.[66][69]

Traditional manuscripts

Paper was invented in China over two millennia ago,[70] based on the "classical definition" of true paper: "paper is a thin tissue composed of any fibrous material whose individual fibers are first separated by mechanical action and then deposited on a mould suspended in water."[71] Permanent paper is denoted by archivists and librarians as "the physical substratum for information that shall last for a long time to come."[70] Traditional manuscripts refer to handwritten documents in historical script, produced by pre-colonial authors, scholars, governments and religious orders.[57][60]

Traditional manuscripts in Southeast Asia were primarily constructed using paper or palm-leaf, [57] both of which are susceptible to natural deterioration or information loss caused by mishandling, theft, or the environment (e.g., inadequate storage facilities, humidity, natural disasters, war).[64] Additionally, palm leaf was often used for religious discourse which was written in specialized script (e.g., Baybayin, Dhamma, Javanese, Jawi, Khmer, Lao, Thai): thus, palm leaf manuscripts require specialized translation and analysis of both languages and handwriting.[72][73] Especially for Southeast Asian countries whose cultural property are the most vulnerable due to economic or social conditions (e.g., Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam), increased attention to the care of ancient materials is intrinsic to preserving their documentary heritage.[64][57]

Field preservation of traditional manuscripts has been applied throughout the region: documents are treated in situ using relevant conservation technology and techniques.[60][57] Because they are not removed from their original site, historical documents are less susceptible to external threats or contaminants.[60]

Conservation efforts can ultimately be assisted by regional collaboration, including transfer of physical resources, appropriate knowledge and expertise.[60][57]

Memory of the World Programme (1992)

The Memory of the World Programme was initiated by UNESCO in 1992 "to safeguard endangered and unique library and archives collection[s], to make [them] available for future generations and to improve [...] accessibility globally."[60] Programme objectives also include: identifying vulnerable library and archival collections, sensitizing governments to preservation demands, and fostering partnerships between countries with similar needs to protect resources of "global knowledge."[74] Southeast Asian nations currently involved in the Programme include: Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines.[74] The Programme maintains a comprehensive Register of its holdings which is useful for communicating awareness of historical documents, including the importance of their long-term preservation for national and regional documentary heritage.[60][74]

Digitization

Digitization, the conversion of analog material (e.g., handwriting, sound imprinted on magnetic tapes, photography on celluloid) to a digital format, is a technique applied to physical records vulnerable to information loss.[75][76] Digital copies (e.g., floppy disks, CDs) are susceptible to machine obsolescence and entail their own preservation concerns; digitization (whereby information exists exclusively in a binary form without a physical support) allows for intermediate intervention of historical materials and the information they communicate.[75] Original documents are still accessible to researchers, though "only according to specific rules, meant to preserve the integrity of the physical documents."[75] Accessibility, (intermediate) storage,[77] and copyright are the predominant reasons archival institutions implement digitization programs.[76]

Digitization requires substantial resources (e.g., funds, scanners, servers, manpower), training and time.[76][77] Digitization can occur internally (on-site) or be outsourced to external vendors, which is one solution for institutions lacking in time and/or manpower to complete digitization projects.[76]

As of 2015, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Singapore have implemented (internally-funded) digitization projects.[76][78][79]

Southeast Asia Digital Library

The US Department of Education's Technological Innovation and Cooperation for Foreign Information Access (TICFIA) dispensed a four-year, $780,000 grant to various global institutions and repositories, resulting in the Southeast Asia Digital Library. The program objective entails providing "free access to archives of textual, still image, sound, and video resources, covering both historical and current information from the region."[80]

Projects include:[80]

- Digitization of palm leaf manuscripts from Northeastern Thailand

- Photographic archive depicting "a century of life in Cambodia"

- Training seminars for librarians in preservation, conservation and digitization at the University of San Carlos' Cebuano Studies Center in the Philippines: resulted in an online archive of images and textual materials

- Video archive of contemporary Indonesian television programming

- Digitization of rare historical records (of various scripts), in collaboration with the British Library and Vietnamese Nom Preservation Foundation

- Video archive of interviews with former political prisoners in East Timor, in collaboration with Australia's Living Memory Project

- Conversion of Ohio University's Berita Database (journal articles and additional materials from Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, and ASEAN) to free, public access

In 2009, the Digital Library received additional funding to facilitate successive initiatives, including:[80]

- Digitization of Buddhist murals and cloth painting in Thai temples

- Digitization of printed Vietnamese Nom materials, art objects and criticism

- Bibliographic database of digitized Islamic manuscripts from Indonesia

- Digitization of archival photographs and videos discussing and documenting Indonesian literature and culture

- Video archives of interviews with Khmer Rouge survivors

- Digitization of Buddhist murals in Laos

Dislocation

See also Archives: A Place, Archives and Repatriation, Postcolonial Archives

Traditional manuscripts were highly valued by 19th & 20th century European collectors: "scribes were paid to copy valuable works of literature for their keep," and occasionally prized documents were presented as "gifts" from the colonized governments to their colonial rulers.[60] Still more manuscripts were transported to the colonials' country of origin "and eventually found themselves housed and preserved in repositories [abroad]."[60] Though European conservation practices have assisted the survival of vulnerable manuscripts,[60] displacement ultimately challenges nations' intellectual and documentary control over their historical materials.

Indonesia

In 1993 the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of UNESCO compiled a series of laws related to Indonesian cultural property, specifically authority the Indonesian government has over the retainment of such property.[81] "Cultural property" as defined by "Law of the Republic of Indonesia Number 5" includes items "which are obtained from descent or heirlooms; or [items] of which there are sufficient numbers of any given type and a representative number are already owned by the state."[81] The law acknowledges the importance of cultural property for purposes of national identity and heritage, including the control over and returning of items rightfully owned by the Indonesian state.[81] Permission to search for missing cultural property is granted only by ministerial petition for purposes of either scientific and technological research or safeguarding and/or preservation.[81]

Malaysia

The acquisition of Malay manuscripts is one facet of the National Library's collection development policy. A major challenge faced by the Centre is retrieval of manuscripts from private residences: "The royal and religious families who own a considerable collection of Malay manuscripts regard them as a family heirloom passed down from generations [...] and are reluctant to allow viewing by others."[60] The inaccessibility of these manuscripts ultimately hinders the Centre's aim to provide a comprehensive database on Malay manuscripts in the country. As a result, the Center has initiated "[c]ampaigns to change the mindset of the private collectors and the general public [...] with regard to the importance of manuscripts as a documentary heritage that should be preserved and made accessible not only nationally but also globally."[60] Furthermore, intra-regional collaboration is necessary to ensure the rightful return of manuscripts which may reside outside the Malay nation-state.[60]

Climate

It is well known in the archival community that physical storage environments have a pronounced affect on record life span: "[e]nvironmental conditions [...] can each affect documents of any kind."[62] Aside from Northern Vietnam and the Myanmar Himalayas which feature a subtropical climate, Southeast Asia's climate is tropical, featuring year-round, relatively high levels of humidity and rain.[82]

Deterioration of archival materials in the tropics is not attributed to one consideration over another; rather, it is a complex process influenced by a number of potentially destructive forces:[62]

- Physical: heat, sunlight, dust, sand

- Chemical: moisture, gases, pollutants

- Biological: fungi, bacteria, insects, rodents

Year-round heat greatly exacerbates the rate of deterioration: "the rule of thumb is that every 10 °C rise in temperature halves the life of a book."[62] When energy elements of light (e.g., ultraviolet radiation) and/or excessive moisture (e.g., humidity) combine with high temperature, oxidation and hydrolysis, two of the greatest threats to textual records' durability, accelerate.[62] Furthermore, "[t]he same fatal combination of heat and moisture creates a suitable environment for biological agents" (e.g., fungi) to thrive and multiply.[62] Gradual deterioration agents are supplemented by the tropics' susceptibility to sudden and destructive natural disasters.[62]

At the national level, funding for sufficient archival storage facilities in Southeast Asia is sparse.[62] Since the early 1990s, countries in mainland Southeast Asia have received financial and technical assistance for conservation efforts primarily through UNESCO programs (such as the "Memory of the World Programme") and similar initiatives based in the United States, Germany, and Australia.[57] Ongoing global attention to and support for the archival needs of developing nations is required to ensure the preservation of national memories and the region's historical, documentary heritage.[57][64]

Specialized Archives

Highlighted Reading

- Burton, Antoinette, ed. After the Imperial Turn: Thinking with and through the Nation. Durham: Duke University Press, 2003.

- Caswell, Michelle. "Khmer Rouge Archives: Accountability, Truth, and Memory in Cambodia." Archival Science 10 (1): 25-44.

- Emmerson, Donald K. 1984. "'Southeast Asia': What's in a Name?" Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 15 (1): 1-21.

- Henchy, Julie. Preservation and Archives in Vietnam. Washington D.C.: Commission on Preservation and Access, 1998.

- Kian-Woon, Kwok and Roxana Vaterson, eds. Contestations of Memory in Southeast Asia. Singapore: NUS Press, 2012.

- Mrázek, Rudolf. Engineers of Happy Land: Technology and Nationalism in a Colony. Princeton University Press, 2002.

- Teygeler, René. "Preservation of Archives in Tropical Climates. An annotated bibliography." Presented at The Preservation of Archives in Tropical Climates (International Council on Archives), Jakarta, Indonesia, 5-8 November 2001.

- Xia, J. 2006. "Scholarly Communication in East and Southeast Asia: Traditions and Challenges." IFLA Journal 32 (2): 104-12.

Related Pages

- Archives: A Place

- Archives and Genocide

- Archives and Repatriation

- Archives and Repressive Regimes

- Archives and War

- Postcolonial Archives

References

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Southeast_Asia

- ↑ ASEAN. 2014. "ASEAN Member States." Accessed March 2015, <http://www.asean.org/asean/asean-member-states>

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 ASEAN. 2014. "ASEAN: Overview." Accessed March 2015, <http://www.asean.org/asean/about-asean/overview>.

- ↑ Emmerson, Donald K. March 1984. "'Southeast Asia’: What’s in a name?” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 15 (1): 1-21.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Emmerson 1984, p. 2

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 "Chapter 11: Southeast Asia." Regional Geography of the World: Globalization, People, and Places (v. 1.0). Accessed April 2015, <http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/regional-geography-of-the-world-globalization-people-and-places/s14-southeast-asia.html>.

- ↑ Shafie, Shaidin, National Archives of Malaysia. 2007. “e-Government Initiatives in Malaysia and the Role of the National Archives of Malaysia in Digital Records Management.” Accessed March 2015, <http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/un-dpadm/unpan041040.pdf>.

- ↑ Chaudhry, Abdus Sattar and Tan Pei Jiun. 2005. "Enhancing access to digital information resources on heritage: A case of development of a taxonomy at the Integrated Museum and Archives System in Singapore.” Journal of Documentation 61 (6): 751-776

- ↑ Griffin, Andrew. 1989. “Myanmar: Strengthening of the National Archives.” United Nations Development Programme, Paris, Accessed March 2015, <http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0008/000842/084222eo.pdf>.

- ↑ Caswell, Michelle. March 2010. “Khmer Rouge archives: accountability, truth, and memory in Cambodia.” Archival Science 10 (1): 25-44.

- ↑ Dean, John F. 1999. "Collections Care in Southeast Asia: Conservation and the Need for the Creation of Micro-Environments." IFLA Publications : A Reader in Preservation and Conservation. 92-111.

- ↑ http://archive.indianexpress.com/news/king-country-and-the-coup/13140/0

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 Ty, Rey. nd. "Colonialism and Nationalism in Southeast Asia." Northern Illinois University. Accessed April 2015, <http://www.seasite.niu.edu/crossroads/ty/colonialism_%20in_se%20asia.htm>.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 14.8 National Archives of Cambodia. "History of our Institution." Accessed April 2015, <http://nac.gov.kh/en/>.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Caswell, Michelle. 2010. "Khmer Rouge archives: accountability, truth, and memory in Cambodia." Archival Science 10:25-44.

- ↑ Caswell 2010, pp. 26, 27

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Caswell 2010, p. 27

- ↑ National Archives of Cambodia. 2015. "Our Collections." Accessed April 2015, <http://www.nac.gov.kh/english/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&id=36&Itemid=29>.

- ↑ Arfanis, Peter. "Introduction to the National Archives of Cambodia." Accessed April 2015, <http://www.khmerstudies.org/download-files/publications/siksacakr/no2/archives.pdf?lbisphpreq=1>.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 National Archives of Cambodia. 2015. "Mission." Accessed April 2015, <http://www.nac.gov.kh/english/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=45&Itemid=56>.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 "National Archives of the Republic of Indonesia." Accessed April 2015, <http://www.indonesia.go.id/en/lpnk/arsip-nasional-republik-indonesia/2481-profile/361-arsip-nasional-republik-indonesia.html>.

- ↑ Bachtiar, Jarsja W. 1971. "Southeast Asian Research Materials: Indonesia." International Library Review 3 (4): 365-66.

- ↑ Bachtiar 1971, p. 365

- ↑ Bachtiar 1971, p. 369

- ↑ Bachtiar 1971, p. 366.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Jantan, Alwi. 1971. "Southeast Asian Research Materials: Malaysia." International Library Review 3 (4): 371-74.

- ↑ National Library of Malaysia. 2010. "Annual Report to CDNL-AO 2010." Accessed April 2015, <http://www.ndl.go.jp/en/cdnlao/meetings/pdf/CR2010_Malaysia.pdf>.

- ↑ National Archive of Malaysia. 2003. "Electronic Records and the National Archives Act." Accessed April 2015, <http://www2.arkib.gov.my/borang/akta_03_eng.pdf>

- ↑ Jantan 1971, p. 371

- ↑ "Electronic Records and the National Archives Act" 2003, p. 2

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Jantan 1971, p. 372

- ↑ National Archives of Malaysia. [date]. "Vision, Mission & Objective National Archives of Malaysia." Accessed April 2015, <http://www.arkib.gov.my/en/web/guest/visi-misi-dan-objektif>.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 Griffin, Andrew. 1989. "Strengthening of the National Archives." UNESCO, United Nations Development Programme, Paris. Accessed February 2015, <http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0008/000842/084222eo.pdf>.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 National Archives Department. 2012. "History." Accessed April 2015, <https://www.mnped.gov.mm/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=28&Itemid=45&lang=en>.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 Xia, J. 2006. "Scholarly Communication in East and Southeast Asia: traditions and challenges." IFLA Journal. 32 (2): 104-112.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 <National Archives Department. 2012. "Scope of Collections." Accessed April 2015, <https://www.mnped.gov.mm/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=32&Itemid=49&lang=en>.

- ↑ National Archives Department. July 2014. "Opening Access to 1963." Accessed April 2015, <https://www.mnped.gov.mm/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=4506%3Aopening-access-to-1963&catid=16%3Aarchives-news&Itemid=100&lang=en>.

- ↑ National Archives Department. 2012. "Services." Accessed April 2015, <https://www.mnped.gov.mm/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=33&Itemid=50&lang=en>.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 National Archives Department. 2012. "Vision, Mission & Objectives." Accessed April 2015, <https://www.mnped.gov.mm/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=29&Itemid=46&lang=en>.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 National Archives of the Philippines. n.d. "History." Accessed April 2015, <http://www.nationalarchives.gov.ph/?cat=12>.

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Quiason, S. D. 1971. "Southeast Asian Research Materials: The Philippines." International Library Review. 3 (4):375-382.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 National Archives of the Philippines. n.d. "List of Collections." Accessed April 2015, <http://www.nationalarchives.gov.ph/?page_id=563>.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 National Archives of the Philippines. n.d. "Mission & Vision." Accessed April 2015, <http://www.nationalarchives.gov.ph/?cat=13>.

- ↑ Anuar, Hedwig. 1971. "Singapore." International Library Review 3 (4): 391-392.

- ↑ Wikipedia. "National Archives of Singapore." Accessed April 2015, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Archives_of_Singapore>.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 National Archives of Singapore. n.d. "History." Accessed April 2015, <http://www.nas.gov.sg/nas/AboutUs/History.aspx>.

- ↑ National Archives of Singapore. n.d. "Access to Records." Accessed April 2015, <http://www.nas.gov.sg/nas/ArchivesReadingRoom/AccesstoRecords.aspx>.

- ↑ National Archives of Singapore. n.d. "Mandate." Accessed April 2015, <http://www.nas.gov.sg/nas/AboutUs/Mandate.aspx>.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 National Archives of Singapore. n.d. "Citizen Archivist Project: About." Accessed April 2015, <http://www.nas.gov.sg/citizenarchivist/About>

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 Swasdisongkram, Choosri. 1971. "Southeast Asian Research Materials: Thailand." International Library Review 3 (4): 395-97.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Fitzgerald, Elizabeth. May 2010. "Thai institutions: Archives." Accessed April 2015, <http://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/newmandala/2010/05/27/thai-institutions-archives/>.

- ↑ Opassiriwit, Chungtong. [date] "The problem and present situation of privacy rights in the digital in Thailand." Accessed April 2015, <http://www.oic.go.th/content_eng/digital.htm>.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 National Archives of Thailand. "History." Accessed April 2015, <http://www.nat.go.th/nat/index.php/history.html>.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 55.3 55.4 55.5 55.6 55.7 55.8 Henchy, Julie. February 1998. "Preservation and Archives in Vietnam." Commission on Preservation and Access, Washington, D.C. Accessed March 2015, <http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED417747.pdf>.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 University of Washington Library. n.d. "Major Libraries and Archival Collections in Viet Nam." Vietnam Studies Group. Accessed April 2015, <https://www.lib.washington.edu/SouthEastAsia/vsg/guides/libraries2.html>.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 57.4 57.5 57.6 57.7 Abhakorn, Rujaya. "Towards a Collective Memory of Mainland Southeast Asia: Preservation of Traditional Manuscripts in Thailand, Laos and Myanmar." in A Reader in Preservation and Conservation, IFLA Publications, eds., Ralph W. Manning and Virginie Kremp. München : Saur, 2000.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Wilder, Gary. “Unthinking French History: Colonial Studies beyond National Identity.” in After the Imperial Turn: Thinking with and Through the Nation. ed. Antoinette M. Burton, Duke University Press: 2003.

- ↑ Gallaher, Carolyn. 2009. "Chapter 9: Colonialism/Imperialism." Key Concepts in Political Geography. Los Angeles : SAGE.

- ↑ 60.00 60.01 60.02 60.03 60.04 60.05 60.06 60.07 60.08 60.09 60.10 60.11 60.12 Omar, Y. Bhg Datin Siti Mariani S.M. 2001. "Preservation of Malay Manuscripts as a National Documentary Heritage : Issues and Recommendations for Regional Cooperation." The Centre for Malay Manuscripts, National Library of Malaysia.

- ↑ 2008. "Colonialism's Effect on Southeast Asia," with bibliography, Accessed April 2015, <http://targetedoutrage.blogspot.ca/2008/06/colonialisms-effect-on-southeast-asia.html>.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 62.3 62.4 62.5 62.6 62.7 Teygeler, René. The Preservation of Archives in Tropical Climates. Report disseminated at the International Council of Archives conference, Jakarta, Indonesia, 5-8 November 2001. <http://www.cool.conservation-us.org/byauth/teygeler/tropical.pdf>.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 63.3 Aung-Thwin, Maitrii. [date] "Chapter 2: Remembering Kings: Archives, Resistance and Memory in Colonial and Post-colonial Burma." in Contestations of Memory in Southeast Asia, eds. Kwok Kian-Woon, Roxana Vaterson.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 64.3 Dean, John F. "Collections Care in Southeast Asia: Conservation and the Need for the Creation of Micro-Environments." in A Reader in Preservation and Conservation, IFLA Publications, eds., Ralph W. Manning and Virginie Kremp. München : Saur, 2000.

- ↑ "Archival Materials: A Practical Definition." archivemati.ca blog post with bibliography, Accessed April 2015, <http://archivemati.ca/2007/01/22/archival-materials-a-practical-definition>.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 <Bos-Rops, Yvonne. "Colonial Legacy in Southeast Asia. The Dutch archives." Stichting Archiefpublicaties. Accessed April 2015, <http://www.kvan.nl/files/S@P/Kolonien%20Vw%20Eng.pdf>.

- ↑ Ballantyne, Tony. “Rereading the Archives and Opening up the Nation-State: Colonial Knowledge in South Asia (and Beyond).” in After the Imperial Turn: Thinking with and Through the Nation. ed. Antoinette M. Burton, Duke University Press: 2003.

- ↑ Cheong, Yong Mun. "Southeast Asian History, Literary Theory, and Chaos." in New Terrains in Southeast Asian History, eds. Abu Talib Ahmad and Tan Liok Ee. Ohio University Press, 2003: 82-103.

- ↑ Dommen, A. 1995. "Documentary materials in the American archives for the history of the kingdom of Laos, 1941-62." South East Asia Research 3(2): 153-168.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Dahlø, Rolf. "The Rationale of Permanent Paper." in A Reader in Preservation and Conservation, IFLA Publications, eds., Ralph W. Manning and Virginie Kremp. München : Saur, 2000.

- ↑ Svensson, Inga-Lisa and Ylwa Alwarsdotter. "A Papermaker's View of the Standard of Permanent Paper, ISO 9706." in A Reader in Preservation and Conservation, IFLA Publications, eds., Ralph W. Manning and Virginie Kremp. München : Saur, 2000.

- ↑ Mahasarakham University. "Project for Palm Leaf Preservation in Northeastern Thailand."

- ↑ Surinta, Olarik and Rapeeporn Chamchong. 2008. "Image Segmentation of Historical Handwriting from Palm Leaf Manuscripts." in Intelligent Information Processing IV, The International Federation for Information Processing. Vol. 288, 2008: 182-189.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 "Memory of the World." UNESCO. Accessed April 2015, <http://www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/flagship-project-activities/memory-of-the-world/homepage/>.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 Pop, Liviu. "Analog, Digital, Postdigital: On the Evolution of Documents." Accessed April 2015, <http://www.academia.edu/2915514/Analog_Digital_Postdigital._On_the_Evolution_of_Documents>.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 76.2 76.3 76.4 Mat, Shaifol Yazam & Aishah Moh Nasir Kolej. 2005. "Digitization and Sustainability of Local Collection: An observation of digitization activities among Malaysian Universities Libraries." Paper presented at World Library and Information Congress: 71st IFLA General Conference and Council, Oslo, Norway: August 2005.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Gould, Sara and Marie-Thérèse Varlamoff. "The Preservation of Digitized Collections: Recent Progress and Persistent Challenges World-wide." in A Reader in Preservation and Conservation, IFLA Publications, eds., Ralph W. Manning and Virginie Kremp. München : Saur, 2000..

- ↑ National Archives of Singapore. Accessed April 2015, <http://www.nas.gov.sg/nas>

- ↑ Darlucio, Virginia E. "Digitizing Records at the National Archives." National Archives of the Philippines. Presented at PAARL's Forum on Digital Debates on Archives, Museums and Libraries, Pasay City, 17 September 2009. Accessed April 2015, <http://www.slideshare.net/PAARL/digitizing-records-at-the-national-archives-2060779>.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 80.2 "About SEADL." Southeast Digital Library, TICFIA program, Accessed April 2015 <http://sea.lib.niu.edu/aboutseadl/project_overview>.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 81.2 81.3 UNESCO, Ministry of Culture and Tourism. 2003. "Compilation of Law and Regulation of the Republic of Indonesia Concerning Items of Cultural Property." Accessed April 2015, <http://www.unesco.org/culture/natlaws/media/pdf/indonesie/indonesia_compilation_of_law_2003_engl_orof.pdf>.

- ↑ <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Southeast_Asia#Climate>.