Course:ARST573/Archives and Repatriation

Archival repatriation is the act or process of returning records to their creator or country of origin. The act of, and desire for, repatriation presents archivists with numerous challenges. Records requested for repatriation often fall into contested territory with multiple creators claiming rights to the record.[1] Records move between groups for multiple reasons, but most commonly they were taken as an act of war.[1] Where colonial governments were in place, records may have been removed from their place of origin when the colonial government withdrew.[2] Records may also hold documentation of language or culture which is considered by its originators to be their cultural and intellectual property.[3] Although historically most requests for repatriation of records occurred between countries,[1] issues around Indigenous claims to records representing their cultural and intellectual property are increasingly important in the discussion of archival repatriation.[4]

Reasons for repatriation

At their most basic level, records function as evidence of the rights and obligations of a nation.[5] They document the historical territory a nation occupied, common memories of the past, legal rights and duties, and culture.[6] These records may also provide an account of wrongs committed against nations or peoples and provide evidence against the nation in whose custody the records reside or be used internally within a nation to address wrongs.[7] Records “are a potent legitimator of a group and its identity”[8] and custody and access of these records effects those documented within them. Control over records has historically represented control over the subjects of those records.[9] Requests for the repatriation of records, then, come from a group’s desire to take back control of their records for themselves.

There are four primary reasons for repatriation claims. These are: that records were made by a group or nation; that they are about a group of nation; that they are in a nation or group’s language; or that they are of a nation or group’s religion.[10] These motivations can be divided into those based on the provenance of the record—i.e. we made these records—and those based on the pertinence of the records—e.g. the records are in our language or document our religion.[10] Records about a group or nation may straddle the line between provenance and pertinence.

Documents made by a nation/group

Records that are made by a nation can take multiple forms. Records may be made by a former government, by an organization, or may be more personal in nature—for example, an ancestor’s diary. Archivally, these records' eligibility for repatriation is the easiest to argue. They have been removed from their creating body and their place of origin. As provenance highlights the rights of records' creators, it follows that records should be returned to their originating body, thus returning records to their original context. Often these records are seized in war,[11] but the reasons for these records ending up outside of their place of origin can be complicated. For example, records may be smuggled out of a country, as is the case with the Iraqi Ba’ath Party Records,[12] or they may reside in the old capital city of a nation which has now broken up, as is the case with records of interest to the Ukraine which reside in Moscow.[13] Records may be removed by emigrants as they change countries, or borders may shift and the custody of records can shift with them.[11]

Although custody of these records may be simple in an archival sense, in a real world scenario it becomes problematized. For example, the records of the German occupation of France in World War II can be claimed by both the French and Germany governments.[13] The Germans can say they are the records of the German administration and so should reside with the rest of the records of the Nazi government. Equally, the French can claim the records represent the local administration at the time, and are vital to understanding the history of the country. Both countries have a right to claim the records and both can argue that their administration created the records.

Documents about a nation/group

These records may not be created within a nation’s borders or by a member of the group claiming them, but there is still debate around their ownership. Chief among these records are the records of colonial governments. Often colonial administrations will remove records of their regime when they withdraw from a country.[14] Although these records reside with their creator, they also have a great deal of meaning to those living in the formerly colonized country as they record their history. Without access to these records, nations and peoples lose some of their ability to critically engage with their past, as is the case in the U.S. Virgin Islands, where records of the Danish colonial government reside in Denmark and the United States and not the islands themselves.[15] Records of military occupations function in much the same way. Allied Command occupied Japan after World War II, and when the occupation ended, records of that occupation were moved to Washington, D.C.[16] Less fraught examples of this desire also exist, as in the early history of the archives of Canada copying records from Britain and France.[17]

These issues are not isolated to nation states. Records of church missions removed at the end of the mission, or reports sent back to church centres from those missions may be subject to repatriation claims by those documented in them, for example.[18] Likewise, the records of ethnographers and anthropologists may be subject to request for repatriation by the groups they studied. This is an especially fraught area in countries built on colonialism, like Canada and the United States, where Indigenous populations still struggle to assert their own identity and retain their culture.

Documents in a nation/group's language

Records that document language often come in the form of anthropological notes or recordings. For Indigenous groups, these records are vital to language revitalization. In British Columbia, the work of early ethnographers is one of many tools being used document and develop languages by First Nations.[19] The notes of early missionaries may also be helpful in restoring our understanding of languages. For example, the notes of Spanish missionary Diego de Landa on the spoken Mayan language provided the key to deciphering Mayan glyphs. [10] Some countries may be interested in documents strictly because they are written in their language. Many national libraries have a policy to collect all material in their national language published at home or abroad,[10] a policy which may extend to archival records considered particularly important or interesting.

Documents of a nation/group's religion

There records may not be made by a group, be about a group, or be in their language, but because of the religious connection people still feel strongly about them. These records represent some of the most contested territory because of this personal connection. The Dead Sea Scrolls, for example, are records which are considered important to many people from many different faiths, despite not being in their language or originating from their country.[10]

The records of ethnographers and missionaries may record important cultural or religious ceremonies of Indigenous peoples. These are equally fraught as there is a long history of colonial ethnographers documenting ceremonies without obtaining permission to do so or, in some cases, explicitly against the wishes of Indigenous communities.[20] Photographs and recordings of these ceremonies are especially problematic.[21] Indigenous communities seeking repatriation of these records may also wish to restrict future access to or destroy the records because they violate cultural protocols.[22]

ICA recommendations on repatriation

ICA Position Paper on Settling Disputed Archival Claims

In 1994, the International Council on Archives resolved that while the records of governments are their inalienable property, realistically the repatriation of records predating 1923 was not possible.[23] Records seized before this date are considered, at least by the ICA, to be at rest—i.e. wherever these records reside currently is now their permanent home and they should not be the focus of repatriation efforts—including all records taken by Napoleon that have not yet been returned. In 1995, The ICA adopted the position paper The View of the Archival Community on Settling Disputed Archival Claims. This short paper came out of the "disputed archival claims arising from the Second World War, decolonisation and the break-up of federations" post-1989.[24] It is based on a pragmatic approach to handling the problem of records repatriation—here referred to as restitution.

The ICA advocates for a multinational consultation process to be undertaken, one which is respectful of international agreements on the movement of cultural property, and is based on previous UNESCO and ICA publications.[24] The consultative group would consider four key principles and come to a decision based on a discussion of:

- The inalienability and imprescriptibility of public records

This principle states that, as national laws agree that public records have the status of "inalienable and imprescriptible public property,"[24] they can only be transferred from one state to another through a legislative act from the state which created them. If this is the case, then records removed as an act of war now residing in the archives of a foreign country are there illegally.

- Provenance and the respect for the integrity of archival fonds

This principle is concerned with respect des fonds and the principle of provenance, two of the foundations of archival theory. It states that, as archives are naturally occurring bodies and not collections, they belong with their creating administration, whose laws ultimately should guide their preservation and destruction. Both breaking up a fonds and acquiring a fonds which does not fall under your jurisdiction go against archival doctrine and cannot be allowed.[24]

- The right of access and the right of reproduction

This principle is based on UNESCO's 1979 recommendation that the concept of common heritage be introduced.[24] It states that, where more than one nation can lay legitimate claim to a fonds, litigation be avoided by embracing this common heritage concept. The state in which the records reside should recognize the claim of the other party and allow the fonds to be copied.

- Equity and international cooperation

The final principle in the Disputed Archival Claims paper takes into account that although the previous three principles might be useful, they are not final and may not be sufficient for settling disputes. Unequal dynamics between a colonized country and its colonizer, for example, may mean that the colonized country feels copies of records represent inadequate restitution for the colonial past. This principle asks for states to take to negotiations with the common goal of fairness, mutual respect, and a willingness to cooperate.[24]

In addition, although it has not been officially adopted by the whole of the ICA, in 1997 the European Union presented a draft policy that stated that private records should be treated as much like government records as possible when considering access and restitution.[23]

Methods of repatriation

Demands for the repatriation of records generally call for the return of the original documents to their place of origin. Although the return of originals is usually called for, it is not always possible. Those who have custody of the records may feel that their preservation is in question if they return to their original creators, especially in times of war.[25] Where there are multiple, legitimate claims to a record group, this issue is further complicated. With only one set of original documents, whose ownership should get precedence? In response to these issues, multiple forms of repatriation have emerged, primarily in the form of producing physical copies of records—for example, Canada’s early archival copy program in Britain and France[26]—or in the form of the digitization of records to be shared—for example, the agreement struck between the U.S. Virgin Islands and Denmark.[27] Copying and digitization are not without their own problems as programs. Whoever has physical custody of the records still has power over them and is therefore in the position to give or deny access to them. In the case of records relating to Indigenous peoples, digitized or copied records may not fulfill the needs of communities; what to Western archivists are recordings of culture may be seen as active embodiments of cultural constructs that were never meant to go outside the community by some Indigenous groups.[28] Custody of records, even for reasons of protection, equals control over those records, and this control questions the other nation’s sovereignty.[29]

Copying of records

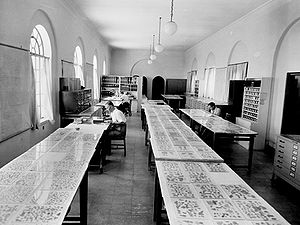

The copying of records as a method of repatriation emerged as a solution to multiple nations having a claim over or wanting access to the same group of records. While states are usually reluctant to cede records completely, copying is often a solution both parties can agree to.[30] Copying records was originally done by clerks, by hand, and a slow, painstaking process.[31] In the mid-twentieth century, the advent of microfilming technology meant that copying could be done much more efficiently.[30] Digitization is often used today as an alternative to microfilm.[27] In some cases, nation's requesting the records may send personnel to copy the records, as was the case in the early history of Canada's archival program.[31] In others, the holding state may make copies for themselves and send the original documents back to the requester.[30] If the holding state plans to dispose of the original records at any time, best practice suggests offering the original records to the state which wished to repatriate them.[30] The state requesting repatriation should also be in charge of deciding the priority for duplication, especially where records may be essential to the continued functioning of government.[30]

Digital repatriation

Digital repatriation is in many ways an extension of copying records for repatriation. Although digitizing records for repatriation means that the recipients of these records do not have physical copies, it also means that it is not necessary for the party making a repatriation claim to have the infrastructure to hold the physical records. In cases where records or copies of the records would be required to travel a great distance to reach their final destination, as in the case of Denmark and the U.S. Virgin Islands, digitization of the records may be seen as safer for the integrity of the records and easier for both nations. As with copying, digital repatriation ensures that all parties involved in the project have a copy of the record. In some cases, the continued custody of the physical record may be contentious among the recipients of digital repatriation because it represents continued control over their records.[32] In others, especially in regards to records not created by but relating to Indigenous peoples that are digitally repatriated to Indigenous peoples, communities may freely acknowledge that records require special handling.[33]

When handling repatriation claims by Indigenous peoples, digital repatriation, although not intended to take the place of physical repatriation entirely, is often looked to as a solution. Indigenous communities often do not have the facilities necessary to house the physical records, and archivists may be reluctant to repatriate records when they are unable to ensure their preservation.[34] Digital repatriation also allows Indigenous people to have access to records without infringing on the right of donors or researchers who may want to use records which would not otherwise by restricted over cultural concerns regarding private, sacred knowledge or practices in the records.[35] This does not mean that digital repatriation is without its issues.

Perhaps more prominent are concerns regarding the online display of records and the easy manipulability of digital files. Databases are generally not built with Indigenous knowledge systems or concerns in mind, and working with systems structured on Western hierarchical systems is problematic for Indigenous users.[36] Each community has difference access restrictions and protocols in place for who can know and see what information.[35] Tools to bridge the gaps between Indigenous knowledge systems and traditional display are starting to be developed in partnership with communities. Systems like the Mukurtu Wumpurrarni-kari Archive, the Plateau Peoples' Web Portal and the Reciprocal Research Network attempt to display materials in a respectful way. These databases allow material to be restricted on multiple levels so that each user has access to unique bodies of records based on their permissions.[35]

Nation-to-Nation repatriation

Prior to the Second World War, the Western world practiced a common diplomatic routine in restoring disputed archives to their originating nations. Although there was no generally accepted over-arching agreement on this routine, it was common practice. Treaties included the surrender or exchange of archives when exchanging territories; the archives to be transferred were agreed upon by both parties involved in the treaty; documents needed to continue the usual course of business and administration were to be transferred from predecessor to successor state "either in original form or as copies"; archives captured during battle were returned once a peace accord was reached; and the archives of occupying military units remained the property of the occupiers.[24] This practice ended in 1945.

At the end of the Second World War, no peace treaty was made with Germany, and there was no effort made towards repatriating any archive captured during the war.[24] Rapid decolonization led to the emergence of new states, but this process occurred without any focus on how to handle the archives of the old and new powers in these countries.[24] This situation was repeated with the end of the Cold War in the late twentieth century, when the breakup of the USSR, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia left many countries without access to the documentation of their previous government. This has led to a vast number of unresolved issues concerning the repatriation of records, one that currently exists in a legal vacuum in the absence of an international agreement on archival repatriation.

Solutions to disputes are often negotiated despite the lack of international accord on archival repatriation. As these disputes often occur when there is some debate about who has a right to hold the records, microfilming or otherwise copying records before repatriating them has become common practice.[37] States which have dissolved or which have broken off of former states may also rely on duplication of records to access their history and set up a functioning administration as painlessly as possible. Records which belong to one nation, but are of interest to another, as is the case with the records of colonial occupation, are also generally copied rather than repatriated fully.[37] In some cases, the repatriation of records may not be politically possible immediately, but over time restrictions to access may be lifted.[37]

Canada, England, and France

Canada began as a series of colonies owned by Britain and France and many records of early Canadian history reside in these countries, as well as other European countries and in the United States.[38] The formation of a Canadian National Archive relied extensively on repatriation efforts through the copying of records, first by hand and then using new technologies to speed up the process. Shortly after Confederation, Douglas Brymner was given responsibility for a new archive programme and began to search for records relating to Canadian history.[38] By 1873, Brymner was in England, assessing records at the British Museum, and in 1874 his colleague from the Montreal Historical Society visited repositories in both London and Paris to do the same.[39] The collection of these records, scattered throughout Europe, as well as throughout the various new provinces of Canada, was integral to the formation of a Canadian national identity and history in the eyes of the new Canadian government "considering the divers [sic] origins, nationalities, religious creeds, and classes of persons...in Canadian society."[38] Having historical records in Canada would allow, supporters of the new archival programme argued, for history to be based on facts rather than hearsay, on hard evidence not "coloured conformably to the political and religious bias or special motives" which might motivate writers of said histories.[38]

In 1878, Brymner began the first official copying programme of the new Archives Branch at the British Museum.[39] Records were transcribed by hand and the copies were sent back to Canada.[40] As the programme expanded to include the British Public Records Office, British officials initially required that "unfavourable passages" be omitted from the copied records—something Brymner objected to strongly and which was eventually dropped as a requirement.[39] In 1883, the copying program expanded to Paris and the French archives, and in 1884 a programme began in Rome.[39] The practice of copying records to add to the Archives continued under the supervision of Arthur Doughty, who primarily sought material from Britain, France, and other European countries.[41] Although not a nation-to-nation exchange, Doughty also set out to visit British and French aristocrats to court permission to copy records—or outright donations—of material related to Canadian history quite successfully.[42] As the twentieth century progressed, so did technology and the advent of micro-photography and photo reproduction meant that copies of records could be created much faster than before,[43] although by this time focus had begun to shift from colonial records to collecting post-Confederation records and managing the public records problem at home.[44]

U.S. Virgin Islands, the United States, and Denmark

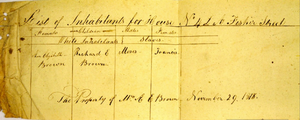

The U.S. Virgin Islands—formerly the Danish West Indies—were sold by Denmark to the United States in 1919. Shortly before this sale, Denmark removed the majority of the records created by their colonial administration between 1661 and 1917.[45] Included in these records were the records of the court cases following the 1848 slave revolt on St. Croix—one of only two revolts that resulted in emancipation of the slave population in the entirety of the Caribbean—which are some of the only documentation of a crucial time in the history of the Virgin Islands.[46] In 1934, the records the Danish administration did not take back to Denmark, primarily records dated 1900 and later, were transferred by the United States to their National Archives, along with post-1917 records created by the American administration.[47] As Denmark and the United States are both legitimate creators or owners of these records, from their perspectives these records were brought home and not taken out of context.[48]

The people of the Virgin Islands disagree. From their perspective, these records document the history of the Virgin Islands and were created in the Virgin Islands and so should be brought back, in some form, so that scholars may have access to the records.[49] Records in Washington, D.C. or Copenhagen are so far removed from the islands that scholars have "little or no access...and no real anticipation of future access"[49] which leaves the people of the Virgin Islands to rely on outsiders to write about their history using primary sources. Although there is a strong tradition of oral history within the Islands.[48] without access to colonial records, the people of the Virgin Islands have no way to negotiate "between official record-keeping and folk history; between the interests of a colonial society and the perceptions of the colonized"[48] and no way of mediating their own past.

This case study problematizes some of the basic arguments behind record custody. Although the Danish and the American administrations did create the records in question, the records of the colonial regime are needed to understand the past in the Virgin Islands.[47] In 1999, Denmark and the Virgin Islands signed an agreement to work together towards providing access to Danish West Indies records, which the National Archives of the United States is also party to.[50] In 2014, the Danish State Archives launched a website documenting the history of the Danish West Indies from 1671-1917. This website, The West-Indies - Sources of history documenting their efforts to scan the majority of the documents in their holdings related to the Virgin Islands. In 2017, these documents will be made available online to all users as a celebration of the 100-year anniversary of the sale of the Virgin Islands to the United States.[51]

Records in private hands

Records subject to repatriation claims do not have to pass from nation to nation. In some cases, records created or collected by a private person may be of significant interest to a state. Usually, the person or organization involved will have resided in the interested nation at some point. This person may have chipped these records to another state, or may have emigrated and took their records with them. In both these cases, the legality of the transfer or records is important. If a creator emigrates with their records, there is usually no question of ownership, although some states, including the European Union, now require export permits for some archives leaving the state.[37] When an individual or organization collects records and moves them from one state to another, the legal situation may be less clear. The legality of the act of collection involved and the rights of the individual or organization to remove records may be called into question.[37] Sir Auriel Stein, for example, collected Buddhist manuscripts in China and shipped them to the United Kingdom--China is now calling for their repatriation.[37]

Individuals or organizations may donate or sell their personal papers to a foreign state. Their state of origin may feel that these records rightly belong in their national archive and not to those of a foreign body. Some countries, like Hungary, have legislation preventing the export of archives without permission, but others, like the United States, do not.[37] Documents may also be stolen or smuggled abroad by individuals, particularly during times of war, whether or not they have the legal right to do so. Although the smuggling of these documents may ultimate save them from destruction, there is often a call for their repatriation after the conflict ends. The controversy over the removal of the Iraqi Ba'ath Party records and Iraq's fight to bring the records home showcases this struggle.[52]

The Lord Dalhousie Collection

The Dalhousie Collection, repatriated to Canada in three stages between 1984 and 1985, consists of a collection of "several hundred paintings, drawings, prints, and maps and plans"[53] which document the twelve years Lord and Lady Dalhousie spent in what is now Canada. From 1816-1820 Lord Dalhousie was Governor of Nova Scotia,[53] and from 1820-1828 he served as Governor General of British North America.[53] Dalhousie contracted artists to travel with him through Canada, generating a number of documentary art pieces that document the proto-Canadian landscape and lifestyle.[54] His map and plan collections provide evidence of early efforts to "solve transportation problems" before railways became a feasible solution in Canada--these document proposed roads, bridges, and canal routes in Upper and Lower Canada,[53] as well as maps of coastal Nova Scotia in the early nineteenth century. Plans of ships, a proposed Governor General's residence that was never built, and rare print collections, as well as a substantial amount of natural history records produced by the Dalhousies are also included in this collection.[54] When the Dalhousies left Canada in 1828, they took all this material home with them to Scotland.[55]

One hundred and fifty years later, Marie Elwood, curator of the Nova Scotia Museum at the time, began a search for the Dalhousie Collection when a letter written by Lord Dalhousie's draughtsman, John Elliot Woolford, was sent to her by a researcher.[55] In this letter, Woolford mentioned the drawings he made for Lord Dalhousie which he had "no doubt [were] still in existence"[55] and speculated still resided with the Dalhousie's. Elwood used the letter as the foundation of a search which eventually brought her into contact with a private collector who had two bound volumes of Woolford's drawings, and the owners of the volumes offered to sell them back to Canada.[55]

Under the Cultural Property Export and Import Act, works that are considered to be of "outstanding importance and national significance"[56] are eligible for a Cultural Property Grant so that they can be brought back into the country. Elwood, representing the Nova Scotia Museum, in conjunction with the National Archives of Canada, was able to obtain one such grant and both volumes were acquired.[57] The first, Sketches in Nova Scotia, resides with the Nova Scotia Museum, and the second, which documents Lord Dalhousie's journey to Niagara, is now in the National Archives.[57] On a second visit to Scotland, Elwood made contact with the direct descendents of Lord Dalhousie and, with a second Cultural Property Grant, acquired thirty-seven watercolours by Woolford for the Nova Scotia Museum, thirty-three of which were later shared with the National Gallery of Canada.[58]

On a third trip, Elwood made her most substantial discovery of records related to Canada's history: a collection of watercolours by Woolford documenting Dalhousie's time in Egypt; a bound portfolio of drawings depicting Quebec City in the 1820s by John Crawford Young, who until this discovery only had seven surviving works; paintings, prints, and drawings by Woolford of Halifax; drawings and notes on Canadian flora as well as notes about Canada by Lady Dalhousie; maps, canal plans, and architectural plans.[58] This material was purchased in 1985 using another Cultural Property Grant and split between the National Gallery, the National Archives, the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, and the Nova Scotia Museum.[58] In 1986, the collection was exhibited for the first time at the Nova Scotia Museum.[59]

The Iraqi Ba'ath Party Records

Hiẓb al-Ba'th al-'Arabī al-Ishtirākī Records (Ba'ath Party Records) at the Hoover Institution

In 2003, Kanan Makiya, an Iraqi-American professor and founder of the Iraq Memory Foundation (IMF) at Harvard University, was in Iraq as an advisor for the Interim Governing Council when a U.S. army officer brought the Ba'ath Party records—at the time, located in a basement—to his attention.[60] Makiya, with permission from U.S. authorities, moved the records first to his parents' home and then, in 2005, to the United States, where they were digitized by the American military and then returned to Makiya.[60] Critics have protested that the decision to remove the records was not one the United States government was empowered to make.[60] Makiya planned to arrange, describe, and preserve these records for the IMF, but the number of records was too much for the relatively small foundation and so in 2008 he entered into an undisclosed agreement with the Hoover Institution (HI) at Stanford University that allowed the HI to take over the work.[61] It is assumed that after the work of arranging, describing, and digitizing the records is done, the IMF will regain full custody of the records.[61]

Saad Bashir Eskander, the director of the Iraq National Library and Archives (INLA), and an outspoken supporter of human rights and government transparency[62], meanwhile, has been calling for the repatriation of the Ba'ath Party Records since 2005. Eskander contacted the U.S. Embassy in Iraq as well as professors at Harvard, arguing that: "These documents are highly sensitive from political and human rights perspective [sic]...They should not be help by any private group, which can use it for its own interests."[62]

The repatriation debate was further complicated when, in 2008, the SAA and ACA issues a joint statement calling for the repatriation of the Ba'ath Party records along with four other collections of records taken from Iraq.[63] The removal of these records was, they argued, an act of pillage.[64] The IMF countered this argument by stating that it was holding the records in trust and was given permission to remove the documents by the Interim Government in 2004.[65] Eskander refuted this assertion, saying that by Iraqi law the IMF's export of the Ba'ath records was "incontrovertibly illegal."[66] A letter from the Iraq Ministry of Culture confirmed Eskander's argument shortly thereafter, and the SAA released another statement reaffirming their call for the repatriation of these records.[67]

The controversy surrounding these records comes not just from arguments over physical custody of the records, but the fight for control over who decides what the national archive of Iraq is.[67] The removal of archives by occupying forces during wartime, especially as an attempt to preserve those records, is a common theme in recent history.[68] In 1991, the Anfal records—records of the Iraqi Secret Police documenting the genocide of Iraqi Kurds—were taken out of Iraq by the U.S. military as potential evidence for an international criminal trial.[69] However, because the Ba'ath Party records were taken by a private organization, their admissibility in court may be called into question due to an uncertain provenance.[70] Although Makiya and the IMF may have felt they were morally in the right removing the records from Iraq, the legality of their removal remains highly questionable.

The Ba'ath records currently reside with the Hoover Institution and discussion over their repatriation has largely moved out of the public eye.[67] Although the records have been digitized, access to the records is granted only to researchers with an Institutional Review Board project approval letter and with a signed user agreement.[71]

Repatriation and Indigenous Peoples

Repatriation of records in relation to Indigenous peoples is doubly complicated because records are generally not created by Indigenous groups, but about them.[72] Records created by Indigenous groups are, in fact, frequently absent from the archive so that the history of Indigenous peoples as represented by the archive is written, generally, by white men and not Indigenous communities themselves.[73] Proponents of repatriation of these records point not to their origin then, but to the context of their creation and the issues that arise from the power dynamics between colonized peoples and their colonizers.[74] Records created by ethnographers and anthropologists may hold knowledge that these outside observers were not given permission to record. For example, anthropologist Marius Barbeau is known to have photographed and taken notes on sacred rituals he was explicitly denied access to.[75] Even where consent was given or informants were paid for their knowledge and objects, anthropologists were not always honest with these informants and the purposes of their studies or the use they would be making of their information.[76]

Indigenous claims over archival materials largely rely on the idea of cultural property or cultural copyright. This position argues that traditional definitions of property and ownership are not applicable to records of Indigenous nations because they do not account for intangible elements like cultural heritage that are contained within these records.[77] The elements of cultural practices, stories, and heritage within these records give Indigenous communities moral—if not legal—rights over them.[78] Indigenous peoples are unique in this envisioning of control because of the histories of “genocide, forced assimilation, and cultural appropriation” these communities faced, as well as “the current context of economic, political, and social disempowerment" that is the reality for many communities.[79]

These issues are further complicated by the fact that Indigenous conceptions of "record" are often not synonymous with Western, colonial notions of what makes a record. Although items like masks or wampum belts are viewed as seen as museum objects in the Euro-western world view, to their originating nations these objects may be considered records.[80] In some ways, it is fortunate if they are as many institutions have policies regarding the repatriation of objects, but very few have given much consideration to the repatriation of records. The United States, for example, has the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act in place. NAGRPA allows Native American and First Nations communities to make repatriation claims on human remains and sacred objects held by cultural institutions in the United States, but does not cover the repatriation of paper records or photographs.[81] Likewise, for some groups—the Māori and Zuni, for example—there is no difference between the sacredness of an object and the sacredness of a representation of that object.[82] A photograph or drawing of a sacred object, then, is of equal concern for these communities when it is outside of their control.

Indigenous Peoples and Digital Repatriation

Because records about Indigenous peoples and their cultures do not fit into traditional archival concepts of ownership, physical repatriation of these records is not usually considered. Efforts tend to focus on alternative repatriation methods, such as distributing physical copies of records or digital repatriation. Although the digitization of materials can provide communities with access to records, these materials are often framed within their original colonizing language, which can be a concern for Indigenous communities, especially where digitization is provided through an institution's open-access website.[83] Caution must be taken when digitizing Indigenous materials, however, because this digitization can lead to harm when existing power structures are maintained in the digital display of records.[84] For example, if the only way an Indigenous group can amend a record or can restrict access to something that should not by publicly accessible is to go through the archivist or curator controlling a database, then this is not true digital repatriation--the same power structures involved in viewing and manipulating the original records are still in place. Researchers like Kimberly Christen have made efforts towards constructing culturally appropriate digital repositories in partnership with Indigenous communities.[85] These repositories attempt to break down the hierarchies present in traditional online displays by giving Indigenous communities direct control over item records and ensuring that Indigenous item records are not interpreted by or subordinate to the views of the collecting anthropologist.[86]

This relates to wider issues regarding records and access. Where physical repatriation of records is not possible, Indigenous communities may wish to assert some level of control over records by requesting that access to them is restricted in some way.[87] As archivists are in charge of access decisions, it is important for archivists who have records related to Indigenous communities in their holdings to attempt to understand Indigenous needs. Restricting access to these records is not the same as censoring these records; it is equivalent to restricting access due to privacy concerns, which falls well within the traditional duties of an archivist.[88] Some archivists also argue for notions of reciprocal curation of records[89] or for positioning archives as "guardians" of records, so that institutions are not owners, but caretakers of these records and have a duty to protect them and to consult Indigenous nations about their handling.[90] Most Indigenous groups acknowledge that records require special handling.[91] Respect for access concerns can help archivists balance the needs of Indigenous communities with the needs of researchers. By being honest about the responsibilities archives have to all members of the community, archivists can establish relationships with Indigenous communities based on mutual respect and trust.[92]

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is often pointed to when discussing Indigenous peoples and archival material because the Declaration implies a requirement for Indigenous peoples to have shared or total control over records relating to their cultural heritage, or for repatriation when that knowledge was recorded without their consent.[93] It is, however, important to acknowledge that Canada, the United States, New Zealand, and Australia—countries where Indigenous peoples are currently living under colonial rule—were the only four member nations to not sign this Declaration when it was intially presented, and have only recently agreed to it.[94] It is also important to acknowledge that "Indigenous" does not represent a homogenous group. Every community will have different concerns unique to their own contexts and histories. Although preferred terms like "Native American" and "First Nations" imply some degree of cohesiveness, these groups represent a collective of many separate nations contained within the same colonial state.

United States of America

Repatriation efforts in the United States are generally guided by the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. This Act gives Native American and First Nations communities the right to claim ownership over human remains and sacred objects in the holdings federally-funded of American institutions, but does not explicitly extend to the repatriation of records.[95] There has not yet been an attempt to use NAGPRA to make a legal claim to documents specifically.[95] This may stem not from a lack of interest in these documents, but from tribes prioritizing the repatriation of ancestors and sacred objects over documentation. It may also come from the fact that many archives with significant Indigenous holdings are inclined to respect cultural concerns without the need of official repatriation claims. It should also be noted that, unlike in Australia and New Zealand, America's repatriation legislation does not include a section on repatriating objects or ancestral remains held by international institutions; tribes who wish to claim material held outside of American must fund themselves.

The National Museum of the American Indian, a Smithsonian branch institution, and its associated Archive Center, are exempt from NAGPRA[96] and instead are governed by the National Museum of the American Indian Act, which states that NMAI must respect and accommodate cultural and religious sensitivities attached to the museum's collections. With this, comes a specific set of principles that states that NMAI follows "ethical precepts and standards that may not be legally necessary" in the view of other Smithsonian units.[97] This means that although the original NMAI Act does not mention archival material, the museum has since amended their policies to include "intangible cultural property" such as the photographs, interviews, and cultural information found in archives.[98] They acknowledge that culturally specific documentation belongs to the cultural group it is associated with, and mandate that staff must obtain permission from that group before any decisions are made regarding the care, handling, or exhibition of that material.[97] NMAI spends an enormous amount of time digitizing its archival holdings to increase their availability. Historically efforts have focused on photographs, but since 2010 NMAI's archival media and paper records have also begun to be digitized for digital repatriation to their cultural owners.[98]

In 2005, the Native American Archives Roundtable was founded within the Society of American Archivists.[99] Inspired by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Library and Information Network Protocols, this roundtable developed the Protocols for Native American Archival Materials in 2006, and presented them to the SAA in 2007.[100] These Protocols describe how archivists might apply the principles of NAGPRA to their holdings. Chiefly, they suggest that archivists might: provide copies for community use and retention, allow community control or co-custody of records in some circumstances; and repatriate records that were illegally obtained or which pretend to repatriated objects or remains.[101] These Protocols have not been endorsed by the SAA, but they represent guidelines for how archivists can work with tribes the determine best practice for their own, unique situations.

SAA Protocols for Native American Archival Materials

The Protocols for Native American Archival Materials were written by a group of nineteen Indigenous and non-Indigenous archivists, librarians, museum curators, historians, and anthropologists from the United States and Canada.[102] They outline opportunities for archives who hold records relating to Aboriginal peoples to cooperate with communities, and best practices for culturally responsive care and use of Native American archival material held by non-Aboriginal organizations. The Protocols address the sovereign nature of Aboriginal nations, issues of collection, handling, preservation, and access and use of these archival materials, and stress the importance of building relationships and understanding differing points of view.[103] The Protocols outline guidelines for both archives and Aboriginal communities to follow when addressing these issues. Repatriation is addressed in the context of NAGPRA.[104] Because NAGPRA doesn't specifically talk about archival documents, the Protocols propose fulfilling the spirit of NAGPRA. They state that archives should cooperate with copy requests made by communities, and that any material obtained illegally should be returned to Indigenous communities.[105] The Protocols entreat non-Aboriginal archivists to consider their materials from the point of view of originating communities and to work towards creating partnerships.[106] The Protocols also touch on the idea of "knowledge repatriation."[107] This is the repatriation of the knowledge contained within the records, if not the records themselves or their facsimiles.

Response to the Protocols

Although the Protocols were completed in 2007 and have been reviewed twice by the Society of American Art, they have yet to be accepted. In 2007, the SAA president created a Task Force to solicit opinions on the Protocols. In 2008, this Task Force submitted their report to the SAA Council for consideration and the Council decided not to endorse the Protocols.[108] Instead, a three session forum occurred was held between 2009-2011 to allow SAA members to discuss and ask questions about the possibility of implementing these Protocols.[108] The chief concerns that came out of both the Task Force and forum sessions were: that the language used in the Protocols—particularly terms like "culturally sensitive"—was unclear; that the Protocols challenged "bedrock" archival principles; that Aboriginal nations had no right to assert protocols from their legal systems over American institutions; that implementation of the Protocols would lead to violation of federal laws; that any time of knowledge, traditional or otherwise, cannot be copyrighted and that copyright cannot be collectively held; that there is no real reason why Native American moral rights should be held above the rights of other stakeholders; that the Protocols might violate the current SAA Code of Ethics by disallowing access to materials; that the authors of the Protocols did not represent all 562 tribes currently recognized in the United States; that boundaries between Native American and non-Native materials were too indistinct; and that the Protocols were unpractical and not faceted enough in their considerations.[109] Although these critics seem stringent, all seven units who responded to the original request for comment on the Protocols expressed support of an open dialogue about the care of Indigenous records and many archivists surveyed openly favoured endorsing the Protocols.[109]

Relying largely on the concepts of group privacy and restorative justice, other archivists have pushed back against these critiques.[110] They argue that archivists need to understand the context of the historical relationships between Native Americans and colonial powers in order to understand the right to access and control that the Protocols argue for.[111] In the view of the proponents of the Protocols, open access infringes on the ethical principle of privacy that is commonly accepted by the archival community and is, in fact, included in the SAA Code of Ethics.[112] They argue that group privacy should be considered as important as individual privacy[113] and that Native American communities are unique because of their history of genocide, forced assimilation, cultural appropriation, economic and political disempowerment in the United States.[114] Critics of the SAA's responses say that archivists who are concerned that other minority groups will claim the same privileges over records if the Protocols are endorsed don't understand that not every minority group has the same relationship with the dominant culture.[115] Others point out that, while the rights of donors and the public are important, they do not automatically cancel the rights of Native American communities.[116] It should be noted that the SAA's lack of endorsement does not necessarily mean that some archives haven't already incorporated aspects of the Protocols into their practice.

Canada

Canada does not currently have any federal repatriation policies in place. In 2000, Alberta adopted the First Nations Sacred Ceremonial Objects Repatriation Act, but this act is limited to the repatriation of objects.[117] Beyond this, the act is somewhat limited in that it stipulates that only items which were "used by a First Nation in the practice of sacred ceremonial traditions" and which are "vital to the practice of the First Nation's sacred ceremonial traditions" are eligible for repatriation.[118] This policy was created largely in response to active lobbying by the Blood tribe and has no effect on instutions which are not both Crown run and located in Alberta.[117] Despite this lack of legislation, most major collecting institutions in Canada have developed repatriation policies to handle First Nations claims.[119] Claims are handled on a case-by-case basis and, because of the current lack of legislation, there is no narrowing of the scope of what communities can ask to have repatriated.

Canada's policies generally follow those of the United States. Since First Nations communities can make claims on objects and remains in American institutions using NAGPRA, there was a need for museums to develop their own policies regarding repatriation. If the SAA endorses the Protocols for Native American Archival Materials, it is highly likely that Canada will follow. As is the case in the United States, the lack of endorsement of the Protocols does not mean that institutions are not already taking them into consideration in the way they are handling Indigenous archival materials. Although the Association of Canadian Archivists provides an Aboriginal Archives Guide, their guide is aimed at Aboriginal communities wishing to develop an archive of their own, and does not provide handling guidelines for non-Indigenous archivists or have the same balance of archivists and Indigenous interests that the Protocols presents, although the Guide does acknowledge that the written record does not fully capture Aboriginal history in Canada. [120] The ACA does have a Special Interest Section on Aboriginal Archives. The SISAA was inspired by the number of archival and records management issues pointed out by the 1996 Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.[121] The SISAA focuses on "archival issues relating to records created by or related to Aboriginal peoples"[121] and aims to engage both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal archivists in open dialogue about concerns surrounding the treatment of these records.

Library and Archives Canada

Although physical repatriation of records has not been undertaken, Library and Archives Canada has taken steps to make their Aboriginal holdings easily accessible. This includes publishing research guides, microfilming Record Group 10—the Indian Affairs record group—and subsequently digitizing this microfilm.[122] They also participate in Project Naming, an ongoing effort to identify Inuit peoples in archival photographs, for over a decade.[123] Efforts like this can be seen as digital or visual repatriation of records, although it should be acknowledged that Project Naming is largely administered by Nunavut Sivuniksavut, an Inuit youth college in Ottawa, and not LAC itself. Archival copying of key Indigenous resources, like RG-10, has been pointed to as a model for other national archives to follow by some researchers.[124]

Australia

The Australian Government Policy on Indigenous Repatriation has been in place since October 2013, following its decision to ratify the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.[125] This policy focuses on ancestral remains and sacred objects, but stipulates that "Traditional Owners should have access to and copies of all relevant documentation concerning their ancestral remains."[126] Under the Repatriation Policy, the Australian government agrees to help fund research towards the repatriation of remains and objects, travel, and the transportation of ancestral remains and sacred objects for return.[125] Australia will help Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities negotiate with foreign governments for the return of remains, but not objects.[125] Although this policy does not extend beyond ancestral remains and sacred objects, its explicit inclusion of documents about remains is a good starting point for communities interested in the repatriation of other documentation.

Significant Court Decisions on Indigenous Knowledge Rights

Australia has also been the sight of significant court cases regarding Indigenous knowledge rights. The Milpurrurru and others v. Indofurn Pty Ltd and others case officially killed the previously wide-spread notion that Aboriginal art was public domain when artist Milpurrurru won a copyright infringement case when carpets featuring his work, Goose Egg Hunt, were sold without his consent or knowledge.[127] In 1997, the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies took joint action with the Badmardi clan and the copyright owners of a rock art book against the maker of a t-shirt range that copied Mimi rock art figures from popular books.[128] The case resulted in the t-shirt company paying damages, handing the shirts over to the Badmardi clan and issuing a public, written apology.[128] Although this case centered on an Aboriginal community working with the copyright holders of the book, the partnership between the community and the publisher points to a willingness on the publisher's part to protect Aboriginal cultural integrity. A 1998 case initially between artists John Bulun Bulun and a textile company resulted in judge Justice von Doussa finding that the artists who record traditional knowledge in their work, as Bulun Bulun did, have an obligation to protect that work from infringement that is contrary to cultural law and customs.[127] This acknowledgement of cultural copyright over traditional knowledge puts Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in the unique position to make repatriation claims on the basis that records which record aspects of their culture, especially sacred aspects, are under their copyright.

In the late 1990s the Australian Law Reform Commission reviewed the federal Archives Law. In light of the past relationship between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the Australian government and the sensitive nature of the past recorded in government records, the ALRC recommended that ownership of government records be transferred from the Commonwealth to Indigenous organizations.[129] It also recommended that the National Archives of Australia make copies of "records of particular significance to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people" and make these copies readily available to communities.[129] While the NAA did not support the transfer of ownership—arguing that, aside from the practicality of actually isolating and transferring all these records, the records would also lose all context if taken out of their original order—they did support the copying of records.[129]

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Library and Information Resources Network Protocols

A main concern of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is secret/sacred materials in the archive. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Library and Information Resources Network Protocols, which inspired the Protocols for Native American Archival Materials, lay out specific handling instructions for identifying and dealing with secret, sacred, and sensitive materials. First, archivists must identify this material; second, they must determine the appropriate policies to follow regarding their handling of this material; and third, they must strictly observe these policies.[130] They stress that consultation with communities is crucial at every stage in this process.[130] The Protocols outline repatriation as a possible solution, but also suggest an "indefinite loan" to the communities, with the institution continuing its maintenance of the materials while communities retain some level of control over them.[130] These protocols stress that although non-Indigenous archivists and researchers may see a photograph or description of an object as a record and not as importance as the physical thing, in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture, there is no difference; it is not a record of culture, but a piece of living culture.[130]

New Zealand

The New Zealand, or Aotearoa, government, like Australia, funds Māori and Moriori tribes in their repatriation efforts both inside New Zealand and internationally.[131] The Karanga Aotearoa Repatriation Programme is administered largely through Te Papa Tongarewa/The Museum of New Zealand and focuses on the return of kōiwi tangata/human remains, including Toi moko, Māori preserved, tattooed heads.[131] Toi moko were a collector's item for anthropologists and tourists alike and left the country in vast numbers prior to 1831, when the scale of the demand for Toi moko was so great that the Sydney Act of 1831 banned their export.[132] Regardless of the ban, a black market for Toi moko still existed for many years.[132] Te Papa is not, however, mandated to repatriate taonga Māori/Māori treasures and focuses only on kōiwi tangata and Toi moko,[133] so it is unlikely that this repatriation policy could be used in efforts to obtain records.

New Zealand/Aotearoa's Unique Context

New Zealand is somewhat unique in its relationship with its Indigenous population in that it was ostensibly founded on a policy of biculturalism. In 1840, the British signed the Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti o Waitangi with Maori chiefs and promised to respect Māori rights to self-determination and to provide an atmosphere of equal rights.[134] Although the extent to which the Crown actually honoured this agreement has been questionable over the years, since the late nineteen eighties New Zealand's government has made a considerable effort to take the principles of Waitangi in mind when enacting legislation.[134] Libraries, museums, and archives have been effected by this shift, particularly Archives New Zealand, the national archive, as the repository that holds both the English and te reo Māori originals of the Treaty.[134] It has become official policy in state institutions to pursue mātauranga Māori, meaning a "system of knowledge used by tangata whenua [people of the land] to interpret and explain the world."[134] This system includes oral histories, genealogy, karakia (prayers and incantations), and waiata (songs).[135] Incorporating mātauranga Māori is usually done through partnership with Māori communities.

These partnerships have led to institutions developing protocols around the management of taonga, including records. The National Library of New Zealand, for example, explicitly states in their preservation policy that "the observation of appropriate tikanga is essential for the preservation of collections"[136]—i.e., Māori protocols must be adhered to in the storage and access of these materials. Archives New Zealand is actively involved in consultation and cooperation with Maori communities and has a Māori consultant group on staff to ensure that Archives New Zealand is a responsive, respectful institution.[137] In general, partnership takes the form of hiring Māori staff when possible, producing finding aids specifically for Māori researchers, and undergoing copying and digitization efforts of key resources similar to Canada's copying of RG-10.[138] This digitization has given Māori some level of control over their own documentation, as access to the online database these records are stored in was reduced to a number of specific locations rather than being freely available online in response to Maori protests.[139] The discussion around control of these documents also led to the Māori Land Court deciding that when Land Court records are no longer in administrative use, Māori have a right to assert their ownership over these records if they archive they are held in is not "perceived as an accessible and trustworthy repository."[140] Although partnership efforts in New Zealand's national institutions go further than in many other countries, they still do not constitute true co-management or bicultural ownership of records. Māori concerns are an additional component to the institution's mandate and are incorporated into programs which are built around British, colonial systems.

See also

External links

ICA Position Paper on Settling Disputed Archival Claims

Cultural Property Export and Import Act The legal act governing the export and import of cultural property in Canada. This Act governs the allocation of Cultural Property Grants and lays of laws regarding the import and export of cultural property belonging to other nations.

The West-Indies - Sources of history The website created by the Denmark State Archives documenting their 250 colonial regime in the Virgin Islands. If everything goes as planned, this website will make digitized formats of all of Denmark's colonial records available for open access on March 31, 2017, to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the sale of the Virgin Island to the United States.

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Often cited by scholars as an indication of the moral rights of Indigenous peoples over records documenting their history and culture. The Declaration has not been ratified by Canada, the United States, Australia, or New Zealand.

Protocols for Native American Archival Materials

SAA Final Report: Native American Protocols Forum Working Group, 2012

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Library and Information Resource Network Protocols The inspiration for the Protocols for Native American Archival Materials.

NMAI Archive Center The National Museum of the American Indian Archive Center's website, including their FAQ.

LAC Aboriginal Heritage Library and Archives Canada's Aboriginal Heritage resource page.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Peterson, Trudy Huskamp. “Macro Archives, Micro States.” Archivaria 50 (2000):41

- ↑ Bastian, Jeanette A. “Taking Custody, Giving Access: A Postcustodial Role for a New Century.” Archivaria 53 (2002): 76-80

- ↑ Mathiesen, Kay. “A Defence of Native Americans’ Rights over Their Traditional Cultural Expressions.” The American Archivist 75 (Fall/Winter 2012): 456-81.

- ↑ See, for example: Bastian, Jeanette A. “Taking Custody, Giving Access: A Postcustodial Role for a New Century.” Archivaria 53 (2002): 76-93.; Christen, Kimberly. “Opening Archives: Respectful Repatriation.” The American Archivist 74 (Spring/Summer 2011): 185-210.; Crouch, Michelle. “Digitization as Repatriation? The National Museum of the American Indian’s Fourth Museum Project.” Journal of Information Ethics 19, no. 1 (2010): 45-56.; First Archivists Circle. Protocols for Native American Archival Materials. Updated September 4, 2007. http://www2.nau.edu/libnap-p/protocols.html. Accessed February 19, 2015.; Mathiesen, Kay. “A Defence of Native Americans’ Rights over Their Traditional Cultural Expressions.” The American Archivist 75 (Fall/Winter 2012): 456-81.

- ↑ Peterson, Trudy Huskamp, “Macro Archives, Micro States,” 42.

- ↑ Ibid., 43.

- ↑ Caswell, Michelle. “‘Thank You Very Much, Now Give Them Back’: Cultural Property and the Fight over the Iraqi Baath Party Records.” The American Archivist 74 (Spring/Summer 2011): 235.

- ↑ Peterson, Trudy Huskamp, “Macro Archives, Micro States,” 43.

- ↑ Bastian, Jeanette A., “Taking Custody, Giving Access," 82.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Peterson, Trudy Huskamp, “Macro Archives, Micro States,” 44.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Ibid., 47.

- ↑ Caswell, Michelle, "Thank you Very Much, Now Give Them Back," 211-40.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Peterson, Trudy Huskamp, “Macro Archives, Micro States,” 45.

- ↑ For example: Bastian, Jeanette A., “Defining Custody: the Impact of Archival Custody on the Relationship Between Communities and their Historical Records in the Information Age: A Case Study of the United States Virgin Islands,” Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pittsburgh, 1999. http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/304537561?accountid=14656.; Wareham, Evelyn. "From Explorers to Evangelists: Archivists, Recordkeeping, and Remembering in the Pacific Islands." Archival Science 2, no.2 (2002): 187-207.

- ↑ Bastian, Jeanette A., “Taking Custody, Giving Access," 76-93.

- ↑ Peterson, Trudy Huskamp, “Macro Archives, Micro States,” 47.

- ↑ Wilson, Ian. “‘A Noble Dream’: The Origins of the Public Archives of Canada.” Archivaria 15 (Winter 1982-83): 16‐35.

- ↑ Peterson, Trudy Huskamp, “Macro Archives, Micro States,” 47.

- ↑ First Peoples' Cultural Council. Report on the Status of B.C. First Nations Languages 2010. Accessed March 15, 2015. http://www.fpcc.ca/files/PDF/2010-report-on-the-status-of-bc-first-nations-languages.pdf

- ↑ Hagan, William. T. "Archival Captive—The American Indian," The American Archivist 41 (1978): 137.

- ↑ Cronin, J. Keri. "Photographic Memory: Image, Identity, and the 'Imaginary Indian' in Three Recent Canadian Exhibitions.” Essays on Canadian Writing 80 (2003): 81-2.

- ↑ Brown, Deirdre and Nicholas, George. “Protecting Indigenous Cultural Property in the Age of Digital Democracy: Institution and Communal Responses to Canadian First Nations and Māori Heritage Concerns.” Journal of Material Culture 17, no. 3 (2012): 314-15.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Peterson, Trudy Huskamp, “Macro Archives, Micro States,” 48.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 24.7 24.8 International Council on Archives. ICA Position Paper on Settling Disputed Archival Claims. Paper adopted by the Executive Committee on the International Council on Archives. Guangzhou. 10-13 April 1995, 1-2.

- ↑ Caswell, Michelle, “Thank You Very Much, Now Give Them Back," 232.

- ↑ Wilson, Ian. "'A Noble Dream': The Origins of the Public Archives of Canada." Archivaria 15, Winter (1983-83): 16-35.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Dansk Statens Arkiver. The West-Indies – A source of history. http://www.virgin-islands-history.org/en/.

- ↑ Janke, Terrie and Iacovino, Livia. “Keeping Cultures Alive: Archives and Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property Rights.” Archival Science 12, no. 2 (2012): 163.

- ↑ Barkan, Elazar. "Amending Historical Injustice." In Claiming the Stones/Naming the Bones: Cultural Property and the Negotiation of National and Ethnic Identity. Edited by Barkan, Elazar and Ronald Bush, 25. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2002.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 Peterson, Trudy Huskamp, “Macro Archives, Micro States,” 49.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Millar, Laura. "Discharging Our Debt: The Evolution of the Total Archives Concept in English Canada." Archivaria 46, Fall (1998): 109.

- ↑ Barkan, Elazar, "Amending Historical Injustice," 25.

- ↑ Wareham, Evelyn, “Our Own Identity," 42.

- ↑ Caswell, Michelle, “Thank You Very Much, Now Give Them Back," 232.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Christen, Kimberly, “Opening Archives: Respectful Repatriation," 186.

- ↑ Brown, Deirdre and Nicholas, George. “Protecting Indigenous Cultural Property,” 320.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 37.5 37.6 Peterson, Trudy Huskamp, “Macro Archives, Micro States,” 49. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "peterson4" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 Wilson, Ian, "A Noble Dream," 18.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 Ibid., 19.

- ↑ Millar, Laura, "Discharging Our Debt," 108.

- ↑ Ibid., 28.

- ↑ Ibid., 29.

- ↑ Millar, Laura, "Discharging Our Debt," 112.

- ↑ Wilson, Ian, "A Noble Dream," 37.

- ↑ Bastian, Jeanette A., “Taking Custody, Giving Access," 77.

- ↑ Ibid., 76.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Ibid., 80.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Ibid., 79

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Ibid., 78

- ↑ Ibid., 92.

- ↑ Dansk Statens Arkiver. "About." The West-Indies - Sources of history. Accessed April 2, 2015. http://www.virgin-islands-history.org/en/about/

- ↑ Caswell, Michelle, "Thank you Very Much, Now Give Them Back," 211-40.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 Elwood, Marie. “Studies in Documents: The Discovery and Repatriation of the Lord Dalhousie Collection.” Archivaria 24 (1987): 108.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Ibid., 109.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 55.3 Ibid., 110.

- ↑ Canada. "Canadian Heritage: Movable Cultural Property Program." Last updated December 4, 2014. Accessed March 30, 2015. http://www.pch.gc.ca/eng/1268673230268/1268675209581.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Elwood, Marie, “Studies in Documents," 111.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 Ibid., 112.

- ↑ Ibid., 115.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 Caswell, Michelle. “Thank You Very Much, Now Give Them Back," 214.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Ibid., 212.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Ibid., 215

- ↑ Ibid., 216.

- ↑ Society of American Archivists and the Association of Canadian Archivists. "SAA/ACA Joint Statement on Iraqi Records." Last modified April 22, 2008. Accessed March 29, 2015. http://www.archivists.org/statements/Iraqirecords.asp.

- ↑ Caswell, Michelle. "Thank You Very Much, Now Give them Back," 218.

- ↑ Ibid., 219.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 Ibid., 220-21.

- ↑ Ibid., 225-26.

- ↑ Ibid., 228.

- ↑ Ibid., 229.

- ↑ Hoover Institution. "Hiẓb al-Ba'th al-'Arabī al-Ishtirākī Records (Ba'ath Party Records)." Accessed March 31, 2015. http://www.hoover.org/library-archives/collections/hizb-al-bath-al-arabi-al-ishtiraki-records-bath-party-records.

- ↑ Shilton, Katie and Ramesh Srinivasan. “Participatory Appraisal and Arrangement for Multicultural Archival Collections.” Archivaria 63 (2007): 89.

- ↑ Hagan, William T., “Archival Captive,” 137.

- ↑ Mathieson, Kay, “A Defence of Native Americans’ Rights,” 461.

- ↑ Nurse, Andrew. "Archives as Narrative: The Politics of Ethnographic Archiving at the National Museum." In Archival Narratives for Canada: Re-Telling Stories in a Changing Landscape. Edited by Garay, Kathleen and Christl Verduyn, 51. Halifax, NS: Fernwood Publishing, 2011.

- ↑ Ibid., 51.

- ↑ Laszlo, Krisztina. “Ethnographic Archival Records and Cultural Property.” Archivaria 61 (2006): 300.

- ↑ Ibid., 301.

- ↑ Mathiesen, Kay, “A Defence of Native Americans’ Rights," 479.

- ↑ Jaimes, M. A. “Wampum.” In American Indian Culture. Edited by Carole A. Barret and Harvey Markowitz, 779. Pasadena, California: Salem Press, 2004.

- ↑ United States. National Parks Service. Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. November 16, 1990. http://www.cr.nps.gov/local-law/FHPL_NAGPRA.pdf.

- ↑ Brown, Deirdre and Nicholas, George. “Protecting Indigenous Cultural Property,” 314.

- ↑ Crouch, Michelle. “Digitization as Repatriation? The National Museum of the American Indian’s Fourth Museum Project.” Journal of Information Ethics 19, no. 1 (2010): 51.

- ↑ Brown, Deirdre and Nicholas, George. “Protecting Indigenous Cultural Property,” 320.

- ↑ Christen, Kimberly. “Opening Archives: Respectful Repatriation.” The American Archivist 74 (Spring/Summer 2011): 186.

- ↑ Ibid., 199-200.

- ↑ Laszlo, Krisztina, “Ethnographic Archival Records and Cultural Property," 305.

- ↑ Ibid., 305-6.; Mathiesen, Kay, “A Defence of Native Americans’ Rights," 461.; Christen, Kimberly. “Opening Archives," 187-93.

- ↑ Ibid., 193.

- ↑ Morse, Bradford W. “Indigenous Human Rights and Knowledge in Archives, Museums, and Libraries: Some International Perspectives with Specific Reference to New Zealand and Canada.” Archival Science 12, no. 2 (2012): 138.; Wareham, Evelyn. “‘Our Own Identity, Our Own Taonga, Our Own Self Coming Back’: Indigenous Voices in New Zealand Record-Keeping.” Archivaria 52 (2001): 39.

- ↑ Ibid., 42.

- ↑ Laszlo, Krisztina, “Ethnographic Archival Records and Cultural Property," 307.

- ↑ Wareham, Evelyn, "Our Own Identity," 29.

- ↑ Morse, Bradford W. “Indigenous Human Rights and Knowledge," 120.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Crouch, Michelle, "Digitization as Repatriation," 47.

- ↑ Ibid., 48.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 O'Neal, Jennifer R. "Going Home: The Digital Return of Films at the National Museum of the American Indian." Museum Anthropology Review 7, no. 1-2 (2013): 167.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 Ibid., 168.

- ↑ Krebs, Allison Boucher. "Native America's Twenty-First-Century Right to Know." Archival Science 12, no. 2 (2012): 182.

- ↑ Ibid., 192.

- ↑ Crouch, Michelle, "Digitization as Repatriation," 50.

- ↑ First Archivists Circle. Protocols for Native American Archival Materials, 1. Updated September 4, 2007. http://www2.nau.edu/libnap-p/protocols.html. Accessed April 4, 2015.

- ↑ Ibid., 4.

- ↑ Ibid., 16.

- ↑ Ibid., 15-17.

- ↑ Ibid., 5-7.

- ↑ Ibid., 17.

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 Society of American Archivists, Final Report: Native American Protocols Forum Working Group, 1.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 Society of American Archivists. Boles, Frank. Report: Task Force Review: Protocols for Native American Archival Materials, 10-11. Washington, DC, February 7-10, 2008. http://files.archivists.org/governance/taskforces/0208-NativeAmProtocols-IIIA.pdf.

- ↑ Mathieson, Kay, “A Defence of Native Americans’ Rights,” 461.

- ↑ Ibid., 461.

- ↑ Society of American Archivists. SAA Core Values Statement and Code of Ethics. Revised January 2012. Accessed April 4, 2015. http://www2.archivists.org/statements/saa-core-values-statement-and-code-of-ethics.

- ↑ Mathieson, Kay, “A Defence of Native Americans’ Rights,” 476.

- ↑ Ibid., 479.

- ↑ Crouch, Michelle, “Digitization as Repatriation," 50.

- ↑ Mathieson, Kay, “A Defence of Native Americans’ Rights,” 466.

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 Keeler, Honor. "Indigenous International Repatriation." Arizona State Law Journal 44, no. 2 (2012): 754.

- ↑ Alberta. First Nations Sacred Ceremonial Objects Repatriation Act, R.S.A. 2000, c. F-14. 1(e)

- ↑ Morse, Bradford W. “Indigenous Human Rights and Knowledge," 132.

- ↑ Association of Canadian Archivists. Aboriginal Archives. http://archivists.ca/sites/default/files/Attachments/Outreach_attachments/Aboriginal_Archives_English_WEB.pdf

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 ACA. Special Interest Section Aboriginal Archives. Accessed April 5, 2015. http://archivists.ca/content/special-interest-section-aboriginal-archives.

- ↑ Canada. Library and Archives Canada. Aboriginal Heritage. Last modified February 28, 2015. Accessed April 5, 2015. http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/aboriginal-heritage/Pages/introduction.aspx#g.

- ↑ Canada. Library and Archives Canada. Project Naming. Last modified January 29, 2009. Accessed April 5, 2015. http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/inuit/index-e.html.

- ↑ Wareham, Evelyn, "Our Own Identity," 38-9.

- ↑ 125.0 125.1 125.2 Australia. Australian Government Policy on Indigenous Repatriation. October 2013. Accessed April 2, 1015. http://arts.gov.au/sites/default/files/indigenous/repatriation/Repatriation%20Policy_10%20Oct%202013.pdf.

- ↑ Ibid., 10.

- ↑ 127.0 127.1 Janke, Terrie and Livia Iacovino, “Keeping Cultures Alive," 158.

- ↑ 128.0 128.1 Ibid., 159.

- ↑ 129.0 129.1 129.2 Ibid., 162.

- ↑ 130.0 130.1 130.2 130.3 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Library, Information and Resource Network. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Library and Information Resources Network Protocols. Revised 2010. Accessed April 4, 2015. http://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/tk/en/databases/creative_heritage/docs/atsilirn_protocols.pdf.

- ↑ 131.0 131.1 Te Papa Tongarewa/The Museum of New Zealand. Karanga Aotearoa. Accessed April 5, 2015. http://www.tepapa.govt.nz/AboutUs/Repatriation/Pages/overview.aspx.

- ↑ 132.0 132.1 Te Papa. Karanga Aotearoa Resources, 20. Accessed April 5, 2015. http://www.tepapa.govt.nz/SiteCollectionDocuments/AboutTePapa/Repatriation/Karanga%20Aotearoa%20Resources.pdf.

- ↑ Ibid., 19.

- ↑ 134.0 134.1 134.2 134.3 Morse, Bradford W. “Indigenous Human Rights and Knowledge," 122-23.

- ↑ Ibid., 124.

- ↑ National Library of New Zealand. Preservation Policy. Accessed April 5, 2015. http://natlib.govt.nz/about-us/strategy-and-policy/preservation-policy.

- ↑ Archives New Zealand. Te Pae Whakawairua. Accessed April 5, 2015. http://archives.govt.nz/about/te-pae-whakawairua.

- ↑ Wareham, Evelyn, "Our Own Identity," 38-9.

- ↑ Ibid., 41.

- ↑ Ibid., 42.