Course:ARST573/Archives – History (Ancient)

Ancient archives are "rooms or sets of rooms for the systematic maintenance and storage of records and documents."[1] Archives are not simply storerooms of discarded records but are actively managed and organized. The ancient archives examined on this page are from the Near East, Greece, and Rome. There are other ancient civilization who used records and archives but they are outside the scope of this page. Several problems exist when studying ancient archives as they are outside the modern definition of archives and so, some say, they cannot properly be called archives.[2]

Ancient Origins

Archives, as a place where records are stored and preserved, have existed for about as long as writing has. Writing was invented to record information so that it did not need to be memorized and so it could be communicated authentically to an audience or audiences over time. The archives was where these records were deposited to be accessed for referenced or further action.[3] Writing was invented by various civilizations in various times: it was invented in Sumer, in southern Mesopotamia ca. 3500-3000 BCE, in Mesoamerica by the Maya ca. 250 CE or earlier, and in China ca. 1200 BCE.[4] Writing was first invented by the Sumerians to communicate over long distances due to trade. They wrote symbols as a way of remembering lists and proving transactions.[5] “These pictographs were impressed onto wet clay which was then dried, and these became official records of commerce.”[6]

The early records that were created and retained consisted of:

- Laws

- Evidence of administrative action

- Financial and accounting

- Taxes

- Military records

- Labour records (voluntary or involuntary

- Government records [7]

Near East

It is in the Near East where there survives the best evidence of ancient archives and archival practices, simply because the records have survived. However, problems with analyzing the archival practices of these ancient archivists arise when the excavators fail to document the archeological context within which these records were found, and the archival bond and original arrangement is lost.[8]Due to the abundance of physical records for this region, a detailed account of all the archival repositories of the Ancient Near East would be enough to fill a book.[9] What follows will be a very brief overview of the records and record keeping practices for this time period.

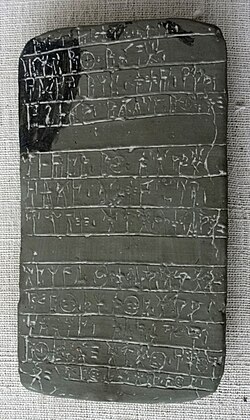

Cuneiform

The script used throughout most of this region is known as cuneiform. The word cuneiform is Latin for wedge-shaped, referring to the shape the stylus makes when it is pressed into clay.[10] Cuneiform writing originated with the ancient Sumerians of Mesopotamia ca. 3500-3000 BCE. It originated as pictographs but evolved into phonograms.[11] “All of the great Mesopotamian civilizations used cuneiform (the Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, Elamites, Hatti, Hittites, Assyrians, Hurrians and others) until it was abandoned in favour of the alphabetic script at some point after 100 BCE.”[12]

Ancient scribes used ivory and wooden boards in addition to clay tablets. These boards could be written on directly or could be covered in a layer of wax, upon which impressions were made with the stylus. However, not much is known about their use as none have survived.[13] Clay tablets with cuneiform text have been uncovered all over Mesopotamia and as far as Egypt, Crete, and Tartaria in Transylvania.[14]

Mesopotamia

Archives in Mesopotamia appeared early on in the 3rd millennium and continued till Antiquity.[15] Clay was a very economical medium to use to record information. Clay was readily available and was very durable once it had been baked by the sun or by fire. If they were baked by fire they would be as hard as rock.[16] One problem with it was that, once it had been baked for preservation, no amendments or annotations could be added, nor could a tablet be used for a continuous record over time as it had to stay moist. As a result, for bookkeeping records, a summary record would be made annually so all the others could be discarded and only that summary kept for reference.[17]

The size and shape of these clay tablets differed greatly across regions and time periods. Eventually, these tablets began to commonly be shaped so the recto was flat and the verso was convex, with thicker edges so they could be written on,[18] like the spine of a book. It is unknown exactly why this specific shape was adopted.[19] Tablets could be shelved like books but a common method of storage was to store tablets in containers, such as baskets, jars, and boxes.[20]

The types of documents kept in Mesopotamian archives included records of short retention, such as bookkeeping records, legal records, and letters,[21] records of permanent retention, such as “legal documents establishing the status of goods and persons, such as titles of property, purchase or exchange contracts, donations, dowries, marriage contracts, adoptions, inheritance,” etc.,[22] and a type of finding aid. This last category consisted of tablets that did not have any seals, unlike the other records. These were lists and memoranda that “make sense only when they can be put back together with the archives to which they belong.”[23] They were used to help organize the archives, as an aid to finding certain records.[24] They may have been kept at the top of a basket containing a series of records so the user could tell at a glance what records were in each basket.[25]

Personal Archives

There were administrative archives in palaces and temples throughout the Near East but a great number of archives of families and individuals were discovered in private homes. “There are no “State archives” but only the accumulation of personal and administrative archives: the archives of the Kings, especially his correspondence, are kept together with the records produced by the different administrative services of the Palace.”[26]

Archaeological evidence shows archives were generally located near the entrance/exit of a building or establishment as this was where transactions were likely to take place.[27] In private homes they were sometimes located in a room in the corner of the house, which would have served as an office, which was separated from the living quarters.[28] Not surprisingly, these private archives are largely found in the homes of the upper class.[29]

Egypt

Very little is known about the archival system in Ancient Egypt. Unlike the rest of the Near East, the material of choice for writing was papyrus and not durable clay tablets. Papyrus was a type of paper “made by placing thin slices of the stem of the papyrus plant side by side” then adding another layer of slices running in the opposite direction of the first. These two layers would then be pressed and beaten together to fuse the layers together.[30] As papyrus paper was made out of an organic material, hardly any has survived from ancient times.[31] Drawings show roles of papyrus documents were stored in chests or jars.[32] A description of the contents of each role was inserted or pasted onto the beginning of each role so they would not have to be unrolled entirely to find out the contents of the role.[33]

Without documents, it is next to impossible to study the archival practices of the ancient Egyptians. However, a large amount of clay tablets were excavated at one site in Egypt, El Amarna, or the city of Akhetaten, the capital city of pharaoh Akhenaten (also known as Amenophis IV).[34] The letters consist of correspondence to the pharaoh but a few are written in Egypt.[35] However, the “archives” appears to be more of a storeroom with no arrangement and just an unorganized heap under the records office of the palace.[36]

Greece

All studies on the archival systems of ancient Greeks must rely solely on literary sources as no physical manifestations of record keeping practices have stood the test of time.[37] One major contribution of ancient Greek archival theory to modern archival science is the origin of the term “archives.” The word derives from the Greek word archeion (ἀρ𝛘εῖον) meaning “government palace, general administrator, office of the magistrate, records office, original records, repository for original records, authority.”[38] The verb form of that word, archeio (ἀρ𝛘ενω), meant command, guide, govern, and the root word, arche (ἀρ𝛘ή), meant origin, foundation, command, power, authority.[39]

Ancient Greece was divided into city states, each with their own political procedures and administration.[40] As a result, archival practices varied greatly from one polis to the next. The records where written on papyrus, ‘whitened boards’ for temporary records, and bronze tablets, though these were quite rare.[41] Public archives were kept either in the Agora or assembly place (such as in Athens), or in temples. Temples were popular as they offered divine protection, to tamper with the records would invite the wrath of the gods. In addition, temples had priest, public officials, and other staff to protect the records.[42] Temples and sanctuaries were often used as treasuries for the same reasons.[43] Temples were also an ideal location as they were usually at a central location within the polis and they were accessible.[44]

Mycenaean Greece

Mycenaean records were written on tablets in a script known as Linear B. These clay tablets were temporary records, recording economic activities and so were all “active” records. This means there were no “official” documents, further indicating a largely illiterate populous.[45] There are no literary texts, no personal letters, nothing to suggest any literacy beyond the scribes of the documents.[46]

More specifically, the Linear B tablets record taxes, in the form of raw materials, acquired at a centralized location. They also record the distribution of these raw materials to manufactures and then the further distribution of manufactured good to people or gods. These records describe the production and storage of goods. They describe agricultural production and the management of livestock. They record land tenures and, finally, they also consist of inventories. [47]

These tablets date from ca. 1200 BCE and are largely found at Pylos.[48] “Pylos is the only Mycenaean palatial centre with a centralized system-dominant location for the collection, processing, and storage of written documents to which the term 'Archives Complex' has been applied.”[49] Other sites exist where Linear B tablets have been found but none of them have such a concentration of tablets in one place as Pylos. This might be due to the method of excavation at these other sites including Knossos and Khania in Crete, Mycenae, Tiryns, Midea, and Thebes on the Greek mainland.[50] The archives at Pylos consists of two rooms in the entrance of the main palace complex and situated along high traffic routes to other parts of the complex.[51] “Its location and arrangement make it accessible for the internal and external flow of information. The room with internal access [room A] seems to have been devoted primarily to clay-tablet filing, storage, and referencing. The room with external access [room B] seems to have been the main locus for the receipt of incoming tablets and information and for temporary storage of texts during the initial stages of information- processing.”[52] The rooms are quite small and the tablets were found on the floor of each room and on the bench in room B.[53] From the distribution of the 767 tablets found in these two rooms, it is possible to get a sense of the possible records management system that was used. Tablets were delivered to room A and stored temporarily till they could be processed in order to find a permanent storage location for them. Shelving and tables may have been set up in this room.[54] Seal impressions in room B give an indication of systematic arrangement and storage of the records within but the method of arrangement is still unknown.[55]

Classical Athens

Athens created the most public records due to “her headlong development, and her management of an Aegean empire.”[56] Many of these records had to be accessible for reference and there is literary evidence that they were consulted.[57]

The most information about archives in Ancient Greece comes from Classical Athens literary sources. Aeschines, a politician and orator who cites the archives and public records to prove his point or discredit his rival, Demosthenes, in speeches to Athenian citizens.[58] In his speech, "On the Embassy", he cites public records and archives as authentic proof:

For at a congress of the Lacedaemonian allies and the other Greeks, in which Amyntas, the father of Philip, being entitled to a seat, was represented by a delegate whose vote was absolutely under his control, he joined the other Greeks in voting to help Athens to recover possession of Amphipolis. As proof of this I presented from the public records the resolution of the Greek congress and the names of those who voted.[59]

For in the public archives you have the record of the dates when you chose the several embassies which you sent out into Hellas, when the war between you and Philip was still in progress, and also the names of the ambassadors; and the men themselves are not in Macedonia, but here in Athens. Now for embassies from foreign states an opportunity to address the assembly of the people is always provided by a decree of the senate. Now he says that the ambassadors from the states of Hellas were present. Come forward, then, Demosthenes, to this platform while I have the floor, and mention the name of any city of Hellas you choose from which you say the ambassadors had at that time arrived. And give us to read the senatorial decrees concerning them from the records in the senate-house, and call as witnesses the ambassadors whom the Athenians had sent out to the various cities. If they testify that they had returned and were not still abroad at the time when the city was concluding the peace, or if you offer in evidence any audience of theirs before the senate, and the corresponding decrees dated at the time of which you speak, I leave the platform and declare myself deserving of death.[60]

You have a practice which in my judgment is most excellent and most useful to those in your midst who are the victims of slander: you preserve for all time in the public archives your decrees, together with their dates and the names of the officials who put them to vote.[61]

You hear that the decree was passed on the third of Munichion. How many days before I set out was it that Cersobleptes lost his kingdom? According to Chares the general it occurred the month before—that is, if Elaphebolion is the month next before Munichion! Was it, then, in my power to save Cersobleptes, who was lost before I set out from home? And now do you imagine that there is one word of truth in his account of what was done in Macedonia or of what was done in Thessaly, when he gives the lie to the senate-house and the public archives, and falsifies the date and the meetings of the assembly?[62]

The dates, fellow citizens, taken from the public archives, have been read and compared in your hearing, and you have heard the witnesses, who further testify that before I was elected ambassador, Phalaecus the Phocian tyrant distrusted us and the Lacedaemonians as well, but put his trust in Philip.[63]

Again, in his speech, "Against Ctesiphon", he continues to rely on the public records and archives for support:

As an answer then to the empty pretexts that they will bring forward, let what I have said suffice. But that Demosthenes was in fact subject to audit at the time when the defendant made his motion, since he held the office of Superintendent of the Theoric Fund as well as the office of Commissioner for the Repair of Walls, and at that time had not rendered to you his account and reckoning for either office, this I will now try to show you from the public records. Read, if you please, in what archonship and in what month and on what day and in what assembly Demosthenes was elected a Superintendent of the Theoric Fund…If now I should prove nothing beyond this, Ctesiphon would be justly convicted, for it is not my complaint that convicts him, but the public records.[64]

An excellent thing, fellow citizens, an excellent thing is the preservation of the public acts. For the record remains undisturbed, and does not shift sides with political turncoats, but whenever the people desire, it gives them opportunity to discern who have been rascals of old, but have now changed face and claim to be honorable men.[65]

These quotes reveal several insights into archival practices and archival theory at the time of Aeschines. Aeschines is able to access the archives, suggesting a certain level of accessibility for citizens. Access was restricted to non-citizens, however it is unknown how often the records were made accessible to citizens.[66] He is able to find the records he needs, suggesting that the records are kept in some logical order to aid accessibility and he knows which records are house in which location, in the public archives or in the senate-house archives. Finally, Aeschines believes these records are authentic and impartial: “the record remains undisturbed, and does not shift sides with political turncoats.”[67]

The Metroön

The Metroön, situated in the Agora, was not central state archives but only housed the records of the Assembly and Council. Records from other official bodies were stored elsewhere, often with the individual officials.[68]

Classical Sparta

In contrast to Athens, Sparta had hardly any state-records. Officials sent letters and kings kept records of the predictions of the Delphic oracle, records of Sparta’s international treaties were erected in other Greek city states but not kept in Sparta. There is one exception, a treaty with Aetolia in the fifth century. Only one other state inscription survives: a list of contributions to a war fund.[69] Laws were not recorded because all Spartans learned state law through their education. “There is no evidence for other records such as citizen-lists, and in the more private sphere named tombstones were generally forbidden. Classical Sparta was a state which seems to have run in all essentials without the help of writing, let alone archives… Our evidence suggests a public use of writing only for the recording of international treaties.”[70]

Rome

Records were written on wooden tablets, coated either in wax or painted white with words scratched onto them, and papyrus, after Rome conquered Egypt.[71] Before public archives came personal archives. Romans would enter information into their adversaria or daybooks about transactions and at the end of each month would compile them into a summary in a book of receipts and expenditures (tabulae accepti et expensi). These records were needed for the census and so had to be preserved in each households personal archives (tablinum).[72]

Republican Rome

The Romans did not have a centralized state archives but housed records in a variety of place, usually temples. Temples had divine protection and so were often used as treasuries and archives.[73] “Moreover, there was the belief that depositing a document in the guardianship of a god made it potent and efficacious. This belief was in keeping with the Roman conception of religio; the word itself refers to the act of binding. By depositing these documents, the Romans hoped to bind the magistrates and people to certain procedures and to obligate their gods to help enforce the measures of which they were the guardians.”[74] Many documents were kept in the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, the patron god of Rome.[75] Plebeians housed their records in the temple of Ceres on the Aventine.[76] It is unknown how accessible these archives were to citizens or even the arrangement of the records within.[77]

Aerarium

Most public records were kept in the aerarium, the state treasury, in the temple of Saturn, which is said to date from the beginning of the Republic.[78] The aerarium was located in a room east of the steps leading to the temple of Saturn.[79] The aerarium housed the records of the quaestores and certain Senate records.[80] However, the aerarium was by no means a centralized public archives.[81] The treasury was overseen by quaestores, who managed public funds. Quaestores were elected officials that only served one year, thus they did not have the time nor training to manage the records and relied on their subordinates.[82]

Tabularium

The Tabularium was built in 79 BCE[83] after a fire on the Capitoline in 83 BCE.[84] It was built out of fire resistant materials.[85] It is impossible to tell how the space was used as an archives[86] as the large hall on the first floor is not suitable for archival storage[87] so scholars have estimated that the second floor housed the records but this theory is not supported by all scholars.[88] The Tabularium is not mentioned in any literary sources, only in one inscription, so there is very little information about the building and its purpose other than the fact that its name suggests it houses tabula (tablets or records). [89]

Roman Empire

Emperors kept the records they accumulated in their personal archives and so the state archives moved to the Palatine hill, in the palace of the emperor.[90] The Tabularium continued to acquire the records of the Senate.[91] Record keeping practices in the Tabularium were not good. In 16 CE, Tiberius appointed three curators tabularum publicarum to recover missing documents and repair damaged records.[92] The emperor kept several archives in his palace. He had a secret archives (secretarium) and notaries of secret documents (notaries secretorum), an archivist of the bedchamber (chartularius cubicularii), and an archivist of the emperor (tabularius).[93]

Problems and Criticism

Ancient archives were very different from modern archives, so much so that some scholars argue that these ancient institutions cannot properly be called “archives.”[94] A major issue limiting the analysis of archives is a lack of standardized terminology that reflect both ancient and modern archival concepts.[95] One of the major problems in determining whether ancient archives were “archives” according to the modern definition or simply storehouses of records with no order or retention is that scholars simply do not know enough about how and why documents were stored, how long the retention period was, if one existed, and how they were arranged.[96]

While there are exceptions, the idea of amassing records from various creators in one place did not exist in the ancient world.[97] This is in contrast to most modern archives where the records of various creators are acquired to fulfill the mandate of the specific archival institution.

In ancient times, there was no distinction between active, semi-active, or inactive records and thus no concept of records life-cycle.[98] There was no notion that a consistent organizational policy was needed to the manage records. There was, however, some recognition that some records were more valuable than others. They realized that some records were more important to keep for long term use than others, useful only for a short time. Laws and treaties needed to be preserved for use longer than the day to day records created and accumulated in the course of administration and transaction. However, this concept was not fully realized and so, ancient archives contain all types of records[99] It is for this reason that Ernst Posner hesitates to call these institutions “archives” as, he states, “even in its broadest meaning the word suggests an intention to keep records in usable order and in premises suitable to that purpose.”[100]

There are several reasons for this lack of information and documentation of past archives and archival methodologies. Firstly, the records may not have survived and so scholars cannot analyze their organization and content. Secondly, when the ancient archives where first excavated, little to know documentation was made about the organization and content of the records nor was their sufficient interest in the economic texts of ancient societies. No archival documentation was used to help interpret or understand the history of these archeological sites and, finally, no connections were made between a site and its archives.[101]

See Also

- Course:ARST573/Archives - History (Medieval)

- Course:ARST573/Archives – History (Early Modern)

- Course:ARST573/Archives – History (Late Modern North American)

References

- ↑ “Archives,” InterPARES 2 Terminology Database. http://www.interpares.org/ip2/ip2_terminology_db.cfm

- ↑ Luciana Duranti, “The Odyssey of Records Managers: From the Dawn of Civilization to the Fall of the Roman Empire,” Records Management Quarterly 23, no. 3 (1989), 5.

- ↑ “Record,” InterPARES 2 Terminology Database. http://www.interpares.org/ip2/ip2_terminology_db.cfm “Archives,” InterPARES 2 Terminology Database. http://www.interpares.org/ip2/ip2_terminology_db.cfm

- ↑ Joshua J. Mark, “Writing,” Ancient History Encyclopedia, last modified April 28, 2011, http://www.ancient.eu/writing/.

- ↑ Mark, “Writing,” Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Mark, “Writing,” Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Ernst Posner, Archives in the Ancient World (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972), 3-4.

- ↑ Maria Brosious, “Ancient Archives and Concepts of Record Keeping: An Introduction,” in Ancient Archives and Archival Traditions: Concepts of Record-Keeping in the Ancient World, edited by Maria Brosious (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 6; Sophie Démare-Lafont, “Zero and Infinity: the Archives in Mesopotamia,” in Archives and Archival Documents in Ancient Societies: Trieste 30 September – 1 October 2011, edited by Michele Faraguna, vol. 4, Legal Documents in Ancient Societies (Trieste: EUT, Edizioni Università di Trieste, 2013), 24.

- ↑ See Olof Pedersén, Archives and Libraries in the Ancient Near East, 1500-300 B.C. (Bethesda: CDL Press, 1998).

- ↑ Joshua J. Mark, “Cuneiform,” Ancient History Encyclopedia, last modified April 28, 2011, http://www.ancient.eu/cuneiform/.

- ↑ Mark, “Cuneiform.”

- ↑ Mark, “Cuneiform.”

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 19.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 25.

- ↑ Antoine Jacquet, “Family Archives in Mesopotamia during the Old Babylonian Period,” in Archives and Archival Documents in Ancient Societies: Trieste 30 September – 1 October 2011, edited by Michele Faraguna, vol. 4, Legal Documents in Ancient Societies (Trieste: EUT, Edizioni Università di Trieste, 2013), 69.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 47, 50.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 51.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 50-51.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 51.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 58-59.

- ↑ Jacquet, “Family Archives in Mesopotamia during the Old Babylonian Period,” 71-72.

- ↑ Jacquet, “Family Archives in Mesopotamia during the Old Babylonian Period,” 75.

- ↑ Jacquet, “Family Archives in Mesopotamia during the Old Babylonian Period,” 78.

- ↑ Jacquet, “Family Archives in Mesopotamia during the Old Babylonian Period,” 78.

- ↑ Jacquet, “Family Archives in Mesopotamia during the Old Babylonian Period,” 80.

- ↑ Jacquet, “Family Archives in Mesopotamia during the Old Babylonian Period,” 69.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 53.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 47.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 48.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 71.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 72.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 86.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 87.

- ↑ William L. Moran, The Amarna Letters (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987), xiii.

- ↑ Moran, The Amarna Letters, xvii; Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 73.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 73.

- ↑ Duranti, “The Odyssey of Records Managers: From the Dawn of Civilization to the Fall of the Roman Empire,” 6.

- ↑ Duranti, “The Odyssey of Records Managers: From the Dawn of Civilization to the Fall of the Roman Empire,” 6.

- ↑ Duranti, “The Odyssey of Records Managers: From the Dawn of Civilization to the Fall of the Roman Empire,” 6.

- ↑ John K. Davies, “Greek Archives: From Record to Monument,” in Ancient Archives and Archival Traditions: Concepts of Record-Keeping in the Ancient World, edited by Maria Brosius (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003) 323.

- ↑ Davies, “Greek Archives: From Record to Monument,” 327-328.

- ↑ Davies, “Greek Archives: From Record to Monument,” 337.

- ↑ Davies, “Greek Archives: From Record to Monument,” 337.

- ↑ Davies, “Greek Archives: From Record to Monument,” 337.

- ↑ Thomas Palaima, “'Archives' and 'Scribes' and Information Hierarchy in Mycenaean Greek Linear B Records,” in Ancient Archives and Archival Traditions: Concepts of Record-Keeping in the Ancient World, edited by Maria Brosius (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 153-154.

- ↑ Palaima, “'Archives' and 'Scribes' and Information Hierarchy in Mycenaean Greek Linear B Records,” 154.

- ↑ Palaima, “'Archives' and 'Scribes' and Information Hierarchy in Mycenaean Greek Linear B Records,” 166.

- ↑ Palaima, “'Archives' and 'Scribes' and Information Hierarchy in Mycenaean Greek Linear B Records,” 155.

- ↑ Palaima, “'Archives' and 'Scribes' and Information Hierarchy in Mycenaean Greek Linear B Records,” 156.

- ↑ Palaima, “'Archives' and 'Scribes' and Information Hierarchy in Mycenaean Greek Linear B Records,” 156.

- ↑ Palaima, “'Archives' and 'Scribes' and Information Hierarchy in Mycenaean Greek Linear B Records,” 177.

- ↑ Palaima, “'Archives' and 'Scribes' and Information Hierarchy in Mycenaean Greek Linear B Records,” 177.

- ↑ Palaima, “'Archives' and 'Scribes' and Information Hierarchy in Mycenaean Greek Linear B Records,” 177-178.

- ↑ Palaima, “'Archives' and 'Scribes' and Information Hierarchy in Mycenaean Greek Linear B Records,” 178-181.

- ↑ Palaima, “'Archives' and 'Scribes' and Information Hierarchy in Mycenaean Greek Linear B Records,” 180-181.

- ↑ Davies, “Greek Archives: From Record to Monument,” 327-328.

- ↑ Davies, “Greek Archives: From Record to Monument,” 327-328.

- ↑ Rosalind Thomas, "Achives in the Ancient World: Record-keeping, Documents, and the 'Stone Archives' of the Greeks,” in Archives and the Metropolis, edited by M.V. Roberts (London: Guildhall Library Publications, 1998), 6.

- ↑ Aeschines, "On the Embassy," II.32

- ↑ Aeschines, "On the Embassy," II.58-59.

- ↑ Aeschines, "On the Embassy," II.89.

- ↑ Aeschines, "On the Embassy," II.92.

- ↑ Aeschines, "On the Embassy," II.135.

- ↑ Aeschines, "Against Ctesiphon," III.24.

- ↑ Aeschines, "Against Ctesiphon," III.75.

- ↑ Davies, “Greek Archives: From Record to Monument,” 337.

- ↑ Aeschines, "Against Ctesiphon," III.75.

- ↑ Rosaline Thomas, Literacy and Orality in Ancient Greece (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 143; Michele Faraguna, “Archives in Classical Athens: Some Observations,” in Archives and Archival Documents in Ancient Societies: Trieste 30 September – 1 October 2011, edited by Michele Faraguna, vol. 4, Legal Documents in Ancient Societies (Trieste: EUT, Edizioni Università di Trieste, 2013), 164.

- ↑ Thomas, Literacy and Orality in Ancient Greece, 136.

- ↑ Thomas, Literacy and Orality in Ancient Greece, 136.

- ↑ Duranti, “The Odyssey of Records Managers: From the Dawn of Civilization to the Fall of the Roman Empire,” 8-9.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 165; Phyllis Culham, “Archives and Alternatives in Republican Rome,” Classical Philology 84, no. 2 (1989), 104.

- ↑ Culham, “Archives and Alternatives in Republican Rome,” 109.

- ↑ Culham, “Archives and Alternatives in Republican Rome,” 109.

- ↑ Culham, “Archives and Alternatives in Republican Rome,” 111.

- ↑ Culham, “Archives and Alternatives in Republican Rome,” 111.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 180.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 165; Mark Cartwright, “Temple of Saturn, Rome,” Ancient History Encyclopedia, last modified December 06, 2013, http://www.ancient.eu /article/636/.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 166.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 166-167.

- ↑ Culham, “Archives and Alternatives in Republican Rome,” 112.

- ↑ Duranti, “The Odyssey of Records Managers: From the Dawn of Civilization to the Fall of the Roman Empire,” 8-9; Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 180.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 166.

- ↑ Culham, “Archives and Alternatives in Republican Rome,” 102.

- ↑ Duranti, “The Odyssey of Records Managers: From the Dawn of Civilization to the Fall of the Roman Empire,” 8.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 178.

- ↑ Culham, “Archives and Alternatives in Republican Rome,” 102.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 178; Culham, “Archives and Alternatives in Republican Rome,” 102.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 178; Culham, “Archives and Alternatives in Republican Rome,” 101.

- ↑ Duranti, “The Odyssey of Records Managers: From the Dawn of Civilization to the Fall of the Roman Empire,” 9.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 191.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 191.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 193.

- ↑ Duranti, “The Odyssey of Records Managers: From the Dawn of Civilization to the Fall of the Roman Empire,” 5.

- ↑ Brosious, “Ancient Archives and Concepts of Record Keeping: An Introduction,” 7.

- ↑ Brosious, “Ancient Archives and Concepts of Record Keeping: An Introduction,” 5.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 4.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 4-5.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 5.

- ↑ Posner, Archives in the Ancient World, 5.

- ↑ Brosious, “Ancient Archives and Concepts of Record Keeping: An Introduction,” 6.