Science:Science Writing Resources/Finding, Identifying and Citing Sources

Finding Sources and Literature Searches

Resources

Scholars choose suitable sources for their research because these sources add relevant details and perspectives to their work. In any form of scholarly communication, the use of other reliable sources helps to signal the scholar’s credibility and knowledgeability about the topic, and locates them as a participant in a broader scholarly conversation that is happening through various published books, articles, and chapters, collectively called the scholarly “literature.”

Scholars work to build knowledge in their discipline, which requires that they engage with the work of others. Scholars rely on particular resources to help find and track what others are saying about a given topic in the scholarly literature. Learning what these are and how to use them is a valuable part of the research process.

Scholarly Resources

SCHOLARLY RESOURCES

The university gives researchers, professors and students alike, access through the library to many types of sources which you can use to develop your knowledge of a topic. To access a wide array of sources, and particularly scholarly sources, which are often behind paywall, the library is the best first stop (start online, but you may need to go in person to find printed sources that lack digital access).

There are several UBC resources that help you find the most relevant sources of scholarly work:

- Use a Research Guide. Research guides help you find specific sources for disciplines that you may not be familiar with.

- If you are a UBC student and/or have a Campus Wide Login (CWL), you can use the UBC Library Home page to find articles, eBooks, theses and much more!

- Check out UBC’s Library Skills Tutorial for modules starting research, finding sources, and citing sources

- If you are a student at another institution, visit your library and/or contact a librarian to find out how to make the most of the amazing resources available to you (on the shelves and online).

- Google Scholar is sometimes recommended to researchers, but it can also cause problems, so be cautious. Google often aggregates drafts and pre-publication versions of works that have not been completely reviewed or met the high degree of rigour provided by peer reviewed scholarly texts. It also can misidentify scholarly sources. Yet, sometimes you can find helpful sources here that may not have appeared in the library search (and if you are logged at UBC or through the UBC VPN, you can click on the source and it will access it via the UBC library still). The key point is that when finding sources through Google Scholar, be sure to always double check that you have the final version and that it is a properly scholarly source (more details on that in the next module about sources). Don’t just trust the search engine because it has “scholar” in the name.

Keeping Track of Your Resources

How can you keep track of all your references?

Develop a working bibliography for your research, where you track the citation information for your sources and add specific annotative notes about what they were about and how they were relevant (or not, if a particular source turned out to be unhelpful despite looking promising). This list will help you remember where you’ve been as you progress, and help you make sure to cite all of your sources as you aggregate information. Having a working bibliography document for your research project helps you avoid hours of searching back again to make sure you work with that source with academic integrity.

There are several programs that allow you to track your sources and add annotations, like a working bibliography app. UBC students and CWL holders can access Refworks for free while at UBC through the UBC Library website. Other free applications include Mendeley and Zotero, which you can use as well. All of these can also help you create your citations for you document, but they often include errors so know which style you are using and double-check them. See the library resource on citation management.

Search Strategies

Search Strategies

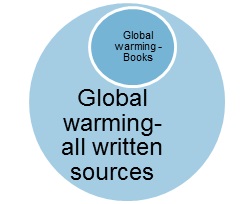

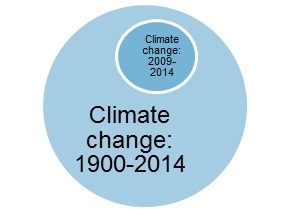

To maximize the effectiveness of using the above resources, you'll need to learn how best to use search tools, including what terms to search and how to use different search platforms. Scholarly writing requires you to find and use credible sources that reflect the ongoing scholarly discourse (e.g. citing a source from 30 years ago about the properties of DNA will not necessarily be a wise move, since knowledge about DNA has developed substantially since).

There are many resources out there, but inefficient searches can sometimes be overly time-consuming and overwhelming. To more efficiently search and find applicable sources, use the strategies in the video below. Keep practicing, and soon searching the scholarly conversation around a topic will seem less daunting and become more focused and even exciting!

Here is a video on helpful strategies to expand and narrow your search:

Ways to Expand and Narrow Search

Video Resources

Need more help?

Watch ‘Grammar Squirrel’s video resources about identifying different sources and integrating them into your science writing on the UBC Science Writing YouTube Channel.

Identifying Different Types of Sources

Different Types of Sources

Choosing suitable sources for any piece of scientific writing – especially a scholarly one, such as a lab report or essay – is extremely important. This is because these sources will help add relevant detail to your writing, provide more information for interested readers, and allow you to share evidence that supports the argument you are developing. The credibility of your writing will directly relate to the quality of the sources you cite, which is why it is so important that you are able to identify the different types before you cite them (primary, secondary and tertiary).

Primary Sources

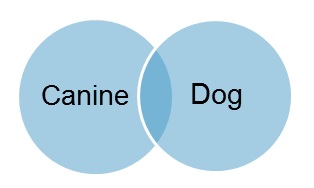

As a rule of thumb, you can think of primary sources as being ‘primary’ because the information in them is coming to you directly from the person/people responsible for it (i.e. it is ‘primary’ because nobody else has adapted the message intended by the original author(s)).

Because the information in primary sources comes straight from the person/people who created it, there is less concern about how another author might have interpreted or misinterpreted the source. Thus, employing primary sources in scholarly writing is generally encouraged.

That being said, how we think about primary sources varies by discipline.

- In STEM disciplines, primary sources detail the results and interpretations of original research and experiments (and are typically written in IMRAD report structure).

- In the Humanities, primary sources are original documents, texts, and materials that are used for analysis and evidence. These might include historical documents, poems, novels, film, newspaper articles, or other archival or multimedia materials. As such, in the Arts, many scholarly articles are in fact “secondary sources” (which we discuss next) that build from non-scholarly primary sources.

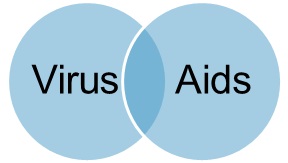

Secondary Sources

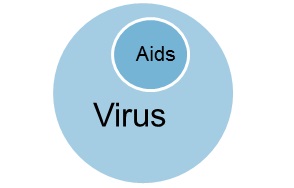

Secondary sources are peer-reviewed texts that build from primary sources, adding layers of synthesis, analysis, and interpretation. As such, they are a step removed from the primary source of evidence or information. How secondary sources function in the scholarly conversation again varies by discipline.

- In STEM disciplines, secondary sources compile primary sources. For example, you could perform a literature search of all primary journal articles published in the past two years on the topic of ‘tropical fish evolution’ and then summarize the latest knowledge on this topic into one article. You would not have performed any of primary research, but have summarized it into a secondary source derived from it.

- Such “review articles” are common in STEM journals, and are often a great way to see the latest developments around a specific topic. However, you must remember that the author(s) of these secondary sources have summarized the primary material (and therefore synthesized and interpreted it), which means that the authors ask readers to also trust their interpretations of the primary sources. For scholars, that can be a big ask.

- Because secondary sources must cite all primary sources that they rely on (including providing a references list), readers have the chance to look back to the original sources to double check the interpretations and accuracy of the secondary source. Using secondary sources in your writing is perfectly OK – so long as you double check any significant claims against the original primary sources. It is your job as a scholar to be assured of the accuracy and credibility of your sources.

- In the Humanities many articles are secondary sources because they work with non-expert primary sources. To reflect the scholarly conversation about a topic in such disciplines, therefore, requires authors to cite frequently from secondary sources. This is markedly different from STEM disciplines, which typically prioritize primary sources.

Tertiary Sources

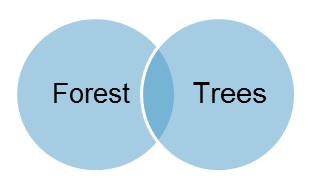

Generally, tertiary sources are not relied on in scholarly communication, in part because they are often not peer-reviewed, but also because of their distance from the sites of inquiry and scholarly conversation.

- Tertiary sources typically only report research/findings, and do not add to them, therefore they aren't typically used as a source in STEM research writing.

- Tertiary sources are compiled from the primary and secondary literature, and are often written in slightly less scholarly terms to appeal to an interested but often non-specialist audience. For example, most encyclopedias and textbooks use information from primary and secondary sources but don’t generally provide references to these sources, making it difficult to check for accuracy or to consult these to add more specific detail to the points the tertiary source makes.

- While tertiary sources, when published by academic publishers, are typically written by subject-matter experts, and can provide a very useful introduction for those new to a field, they are less credible as a source because they rely on the reader accepting the content without double-checking claims against the primary and secondary sources.

- Generally, avoid using tertiary sources in your writing; rather, focus on primary and secondary sources, because they are where the more focused and reliable scholarly conversation happens.

It is also important to understand that although there are types of sources (such as journal articles, review articles, blogs etc.) that typically fall into the primary, secondary, tertiary classification system, it is not the format that makes them one of these types; it is purely the link between the author(s) and the material itself, whether the material has been peer-reviewed, and how specific the information in it is.

Why Does This Matter?

Understanding the different ways knowledge is made and how it is shared can help us navigate the roles that a particular piece of scholarly writing takes as an addition to, or a summary of, the conversation. It also allows us to read, interpret, synthesize, and engage with this conversation from various vantage points and degrees of detail. Often, it is useful to start with a tertiary source from an expert voice we trust, to get a general sense of how the scholarly research has developed in the past, before jumping into primary and secondary sources that are more cutting edge and relevant to your own research.

As we’ve seen, different disciplines produce and engage with primary and secondary sources differently. In the Humanities, most of the scholarly discourse happens in and between secondary sources, and so your work should do the same. On the other hand, in STEM disciplines, scholars attend primarily to primary sources, with secondary sources providing added synthesis and review. In light of this, when looking for sources, you should first analyze how the disciplinary knowledge is being made and shared (and what task is required of you in response to it). Then, modulate your own research and writing accordingly in relation to these sources.

Video Resource

For a recap and for some extra information about identifying different types of sources for use in your writing, please watch Grammar Squirrel’s video on the UBC Science Writing YouTube channel. Included in this are two questions that can be applied to any source to help you decide whether it is a primary, secondary or tertiary source.

We then suggest you complete the quick quiz (below) to see whether you have mastered some of the important skills relating to identifying different types of sources.

Identifying Different Sources Quick Quiz

1) Decide whether the following five sources are primary, secondary, or tertiary (five marks):

- a) A newspaper article about the potential effects of climate change in BC featuring summaries of information from many other sources

- b) A M.Sc. dissertation in which climate change effects on native plants were studied

- c) A review of current knowledge about the effects of climate change that appeared in a high-profile journal

- d) A textbook that covers climate change and other bio-geographical concepts

- e) A blog post from the original author of some research in climate change that basically reprints the journal article that included this research

2) You are writing an article about the effects of climate change in BC for the local newspaper. Rank the types of sources you should use to find the most accurate information (from most accurate to least accurate, three marks).

Most =

Intermediate =

Least =

3) Choose the most appropriate word to complete the sentences below (two marks):

It is never/sometimes/always acceptable to use tertiary sources in scientific writing. Secondary sources will always/generally be more reliable than tertiary sources in ensuring the original source of the material is correctly interpreted.

Quick Quiz Answer Key

To check your answers and see whether you are now a wizard at identifying different types of sources, access the answer key here.

Integrating and Citing Sources

Integrating and Citing Sources

Citation, or the practice of documenting the sources you use in your writing, is a core element of academic research and writing, regardless of discipline. Citing sources not only allows you to document the scholarly conversation into which you’re entering. This is part of producing knowledge; documenting what and who you’ve read in the course of writing your paper is a mark of effective scholarship that meets the expectations of academic integrity.

What and When to Cite

It can be difficult to know when and what to cite. You always need to cite:

- Ideas, concepts, opinions of others

- Direct quotes, summaries, and paraphrases

- Facts used as evidence

- Tables, graphs, or figures produced by anyone but yourself

- Specific statistics or data

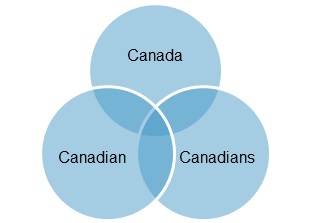

You may have heard that you don’t need to cite your source when the information you’re including is common knowledge. Generally, common knowledge can be understood as information that an average reader would accept without having to look up. This includes:

- Information that most people know (such as that water freezes at 0 degrees Celsius),

- Information shared by a cultural or national group (such as the names of Canadian prime ministers)

- Knowledge shared by members of a field or discipline (such as that a double bond is stronger than a single bond)

However, it can be difficult to know what counts as common knowledge, because an “average reader” is audience and discipline specific. What might be common knowledge in one cultural group or academic discipline may not be common knowledge in another. Here are some ways to determine if something is common knowledge or not:

- Ask: who is my audience and what can I assume they already know?

- See if the information is cited or not in academic scholarship. If the information is cited in at least three different sources, it’s probably common knowledge

- If you are not sure, assume the information is not common knowledge and cite. It’s always better to over-cite than under-cite.

Citation Formatting

Proper citation includes two parts: in-text citations and a complete reference list of sources from which these arose. In-text citations show the reader the specific information you have used in your paper and where exactly you draw on these sources in your discussion. The list of sources at the end of your paper gives the exact references you used, which allows anyone to easily find and refer back to them.

In STEM disciplines, there are different ways to format and organize citations, and these “style guides” are discipline-specific (and sometimes course-specific) (Hochberg, 2019, p. 14). Be sure to check with your instructor about which style they would prefer before you write your first lab report or paper.

| Chemistry | American Chemical Society | ACS Citation Style Guide |

| Mathematics | American Mathematical Style | AMS Style Guide |

| Psychology and many other social science disciplines | American Psychological Association | APA Citation Style Guide |

| Some Engineering disciplines | American Society of Civil Engineers | ASCE Citation Style Guide |

| Various STEM disciplines | The University of Chicago Press | Chicago Manual of Style |

| Biology and other various STEM disciplines | Council of Science Editors | CSE Citation Name-Year Style Guide |

| Various engineering disciplines including:

Civil Engineering, Biomedical Engineering, Electrical and Computer Engineering |

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers | IEEE Editorial Style Manual |

| Medical and Scientific journals; various Engineering disciplines | International Committee of Medical Journal Editors | Vancouver Style |

| Physics | American Institute of Physics | AIP Citation Style |

When deciding which style of citing to use, make sure you follow any directions you were given. Once you choose a style, you must stick to it throughout your whole article. It is very important to be consistent with your formatting; it makes it easier for the reader to follow!

Check out UBC’s Library Tutorial on Citing Sources for a series of helpful videos!

Some Examples

These examples are designed to highlight how each style of citing can be used. Although there is sometimes flexibility when citing, remember to check with your instructor which style you should use. If he/she is happy for you to use either one, make sure you are always consistent in your formatting style (i.e. don’t mix the two styles in one piece of writing).

Expanded Referencing:

- A) Blue, left-handed widgets are actually wodgets (Smith, 1993).

- B) Bloggs et al. (1995) confirmed that …

- C) Smith and Jones (1995) wrote that…

Abbreviated Referencing:

- A) Blue, left-handed widgets are actually wodgets3.

- B) Bloggs et al.2 confirmed…

- C) Smith and Jones [2] wrote that…

Advantages

Table 2: Advantages of expanded and abbreviated referencing

| Style of citing | Advantage |

|---|---|

| Expanded Referencing | • author/researcher is found in text (easily recognizable for a researcher in the field) • show date of research (current) |

| Abbreviated Referencing | • saves time • saves space (no extra words- names, dates) |

When deciding which style of citing to use, keep in mind the advantages of both, but make sure you follow any directions you were given. Once you choose a style, you must stick to it throughout your whole article. It is very important to be consistent with your formatting; it makes it easier for the reader to follow!

Paraphrasing and Quoting

Paraphrasing means putting something that someone else has written into your own words, phrasing and sentence structure.

- Because you’re presenting someone else’s ideas (even though you’re not saying it in exactly the same way), it’s important to acknowledge this with a citation.

- Paraphrasing is useful because it shows that you have an understanding of the material and it allows you to keep your writing concise.

Quoting means reproducing the same words that someone else has written.

- Not only does a quotation need an in-text citation with a page number, but it also needs to be presented in quotation marks.

- Use quotations if a piece of information is well-phrased or unique and cannot be simply rephrased to have the same effect. For example, don’t write: Cliff et al. (1989) reported that “A total of 591 great white sharks Carcharodon carcharias were caught between 1974 and 1988 in the gill nets which are maintained along the Natal coast to protect bathers from shark attack” (p. 77). Instead, write something like: Nearly 600 great white sharks were caught in gill nets along the Natal coast between 1974 and 1988 (Cliff et al., 1989, p. 77).

Reporting Expressions

One way of making sure that you’re signalling to your reader when you’re including someone else’s work is to use something called a “reporting expression.” Reporting expressions signal that you are summarizing or reporting what someone else has written. Examples of reporting expressions include words such as writes, argues, finds, demonstrates, suggests, claims, explains, or shows.

Reporting expressions also allow you as a writer to take a position. For example, writing “Reilly (2010) shows that more than one cup of coffee slows response rates in people” is different than writing “Reilly (2010) suggests that more than one cup of coffee slows response rates in people.” Here, “shows” implies that you agree with Reilly, whereas “suggests” implies that you might have some uncertainty about Reilly’s research. It’s important to choose your reporting expressions carefully!

A helpful hint with citing: if you’re using a reporting expression, you still need to include an in-text citation. This is because you’re reporting what someone else has written, and you need to be sure to credit them for their work.

Further reading:

- Thompson Rivers University Writing Centre's Reporting Words/Phrases

- University of Adelaide's Writing Centre Learning Guide on Verbs for Reporting

Video Resource

For a recap and for some extra information on citing and integrating sources, please watch Grammar Squirrel’s video on the UBC Science Writing YouTube channel.

We then suggest you complete the quick quiz (below) to see whether you have mastered some of the important skills relating to effective use of citing and integrating sources.

Integrating and Citing Sources Quick Quiz

1. Read the following pieces of information taken from real sources. First decide whether they should be quoted directly, or paraphrased and cited (1 mark each). Then use the ‘Expanded Referencing’ style of citing to credit the source correctly with an in-text citation (1 mark each).

A) ‘Furthermore, although there are no demonstrated health benefits from having selenium intake above physiological requirements, there is a general perception that increased selenium ingestion is beneficial, which has led to a flourishing market in selenium supplements.’

This information was written by Kevin Andrew Francesconi and Richard Pannier in 2004.

B) ‘Telomeres are specialized structures found at the natural ends of eukaryotic linear chromosomes.’

This information was written by Vicki Lundblad and Jack Szostak in 1989.

C) ‘I’m so excited – this new discovery blows the old belief clean out of the water.’

This information was written by Mitchell Tonker in November 2007.

D) ‘Changes to the conformation of coding and non-coding RNAs form the basis of elements of genetic regulation and provide an important source of complexity, which drives many of the fundamental processes of life.’

This information was written by Elizabeth A Dethoff, Katja Petzold, Jeetender Chugh, Anette Casiano-Negroni and Mustoe and Hasham M Al-Hashimi in 2012.

2. Decide whether the pieces of information below should or should not be cited (1 mark each, 4 marks total).

a) You are writing a paper to a chemistry audience on the effects of hydrogen bonding in DNA. Should you include a citation for a basic definition of what hydrogen bonding is?

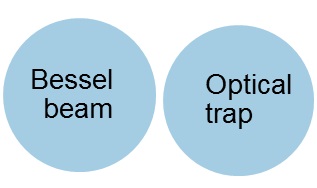

b) You have been working with a Bessel beam optical trap to determine the changes in aerosol particles in relation to relative humidity changes. As you write your paper, you decide to include background information on Bessel beam traps and previous research into the change in aerosol particles against different relative humidities. Should you cite these?

c) You are doing the research for a paper on the separation of chiral compounds and come across a repeated reference to ‘Pirkle phases.’ This term is new to you and it has never been discussed in class, but you have encountered references to it in several articles. You notice that each author actually cites an original article by Pirkle, the chemist for whom it was named. You include the ‘Pirkle phases’ in your paper. Should you cite this paper?

d) You are writing a newspaper article about the most devastating earthquakes of all time. Should you cite a source that says the Valdivia quake (the greatest magnitude in history) occurred on May 22, 1960?

Quick Quiz Answer Key

To check your answers and see whether you are now a wizard at integrating and citing sources effectively in your science writing, you should access the answer key here.