Rape Culture

Overview

Rape culture is a term developed in the 1970’s during second-wave feminism. [1] It refers to a culture in which sexual violence towards women is normalized, condoned, and deemed inevitable.[2] Rape culture encompasses victim blaming, the normalization of aggression, the trivialization of rape and consent, as well as the objectification of the female body, and the prevalence of rape in the media. In other words, rape culture is a system of beliefs which encourages male sexual aggression and condones violence against women by normalizing, trivializing, and eroticizing male violence against women and blames victims for their abuse. Rape culture is so prevalent in today’s society that data from Statistics Canada reveal that one in three Canadian women will experience sexual assault at some point during their lifetime.[3] Sexual assault is identified as one of the most under-reported crimes in Canada[3], with acquaintance sexual assault particularly being the most under-reported.[4][5] An overwhelming number of sexual assaults remain unreported each year as only 6% of such cases are disclosed to authorities.[4][5] Women are deterred from reporting their assaults to the police due to an array of reasons, including internalized feelings of shame and guilt, self-blame, and extreme fear of being doubted.[3] Rape culture is sustained and propagated in society through victim blaming, glorification of sexual violence, and lack of discipline towards perpetrators of violence against women.

Victim Blaming

In Rape culture, the blame for sexual violence is placed upon the victim. Common themes of victim blaming include excessive consumption of alcohol, leading the rapist on, or indecent clothing choices. Leniency towards perpetrators of rape is often practiced, whereas victims are harshly judged by the media or otherwise.[6] It has been argued that victim blaming and rape are methods of social control that maintain a patriarchal society. In areas where the status of women is lower than that of men, incidences of rape are higher, supporting the claim that rape can be a method of social control.[7] Women are taught to prevent rape by not staying out late, or not drinking too much for example. This placing of the responsibility on women’s shoulders shifts some of the blame away from rapists. The focus is placed on women learning not to get raped rather than men not raping.[7]

Rape Myths

The displacement of blame away from the perpetrator and onto the victim is attributable to the internalization of rape myths.[8]. Rape myths are regarded as erroneous, highly pervasive beliefs and attitudes that trivialize, justify, and uphold sexual male violence against women.[8][5] Though rape myths may be community- and/or culture-specific, they generally involve skepticism towards rape claims, holding the victim accountable for their rape, and implications that only particular kinds of women are at risk for sexual assaults and rape.[8][5][9] These problematic ideologies shift guilt and shame onto the victims, thereby absolving perpetrators of responsibility. They allow people to judge whether the rape is actually considered a real rape. Rape myths allow for people to make the assault more normal, trying to blame the victim saying they wanted what they got. Rape myths exist for many reasons, and they involve having certain expectations for gender roles, societal acceptance of violence, and due to misinformation of the sexual assault. The relationship between rape myth acceptance and victim blaming is established through various studies illustrating that “high levels of rape myth acceptance are consistently associated with high levels of victim-blaming" (p. 445). This finding suggests that greater internalization of rape myths translate into stronger stigmatizing attitudes towards victims of rape and sexual assault.[8]

The widespread influence of these cognitive distortions extends beyond the general public and into the justice system, with police and prosecutors demonstrating bias.[8][10] A 1991 study by Frohmann reveals that prosecutors were inclined to reject rape and sexual assault cases when victims reported "unfavorable" behavior (e.g., intoxication, involvement of flirtation/seduction, consent to any sexual activity prior to assault) that align with rape myth and victim blaming ideologies.[10] This method is used to discredit the sexual assault allegations of victims, thus greatly affecting case prosecution and overall conviction rates for these types of offenses.[8]

Sexual Objectification

Viewing a person, or partner as an object, individuals are most likely going to view the partner as a possession. When women are seen as objects they will be abused and raped throughout our society. In our culture it would not be right or normal to beat or rape "humans" but it would be completely normal to beat or rape an "object." Repeated objectification leads women to begin to self-objectify themselves. This kind of behaviour could lead women to feel very ashamed of themselves, causing them to have low self-esteem. They would begin to worry that they do not meet the cultural that need to met in order to meet the standards of beauty. This leads women to always evaluate their looks and contribute to many disorders. Many include depression, sexual dysfunction, bulimia, or anorexia. Objectification is linked to dissatisfaction, shaming the body, and appearance anxiety. It may not seem this way, but women in the mainstream media are still portrayed as objects. Objectification of women, as well as sexualisation of violence, is seen in many advertisements, video games, pornography, movies, music videos, and much more. This makes women a submissive, inferior, and sexually obtainable. Whereas men are displayed as superior, dominant, aggressive, and most definitely violent. This thought sends a message to the society, that women are objects that men can act upon with violence, and rape.

Harassment against Women

An example of Objectification is street harassment. Men have promoted harassment as "fun" and they consider harassing someone as being playful. But other men, do it purposefully, to humiliate women and make them upset. This gives men power in society and allows them to keep women as their submissive. Although not as severe as rape and violence, street harassment degrades women and their stems an idea that women only exist to please men. It also promotes that men are entitled to women’s bodies. The photo of women in a vending machine compares women to soft drinks. There is a male dominance in this photo as all four women in the photo are trapped, moreover, the man in the photo has a choice of which “women” he chooses to have. Another example is Dolce and Gabbana, the way this brand is sold is through gang rape. Pinning a woman down to the ground while three other men stand around watching is very aggressive, and shows male dominance. Lastly in a very popular music video, called Blurred Lines by Robin Thicke, there is a mockery of women’s’ consent in having sex in the song. It is even called a “Rape anthem” for the language that conveys a powerful message that whatever a woman says or does, it means that she has decided to have sex with Robin.

Effects of Harrassment on Women

Harassment affects women harshly, and it affects women as a society and individually. Women have a difficult time meeting and trusting men due to fear. Women are also limited in where they go, due to the fear of mostly men. Women who experience their fear are usually told, or feel that they have an irrational fear. Individually, women may show that they are not upset, but harassment scars and leaves women upset long after they are harassed. This may make them feel insecure, closed off, and less safe around men that do harass. Many women may feel ashamed of themselves, or get very uncomfortable with any individual.

Misogyny

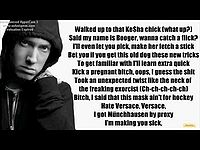

Misogyny is the distrust or prejudice against all women can drive many factors like victim blaming, objectification, and sexism. Blatantly misogynistic messages are also conveyed in our society which contributes to the rape and abuse of women. There are lyrics, and images everywhere in society that are misogynistic. An example of misogynistic lyrics can come from anywhere but Eminem a popular artist has many disturbing lyrics in many of his songs.

Popular Culture and Media

Rape Culture is especially noticeable in media and pop culture. Music videos such as Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines”[11] exemplify a culture that accepts objectification of women as well as lyrics ignoring women’s choice in sexual activity. Movies and Television also contribute to the image of women as passive sex objects. Women in popular media are often portrayed as weak and there for men to enjoy looking at or using sexually.[12]Advertisements such as Dolce & Gabbana’s Esquire spread or Calvin Klein’s Australian ad campaign portray gang rape in particular as glamorous[13] Violence is portrayed as sexy and desirable. The media’s obsession with perfection in women’s bodies also serves to dehumanize women and reduce them to a body rather than a person[12]. All of these images and messages combine to form a social climate where women are thought of as subordinate to men, and therefore subjected to sexual violence. Media also plays a large role in promoting acceptance of Rape culture. In many cases, victims are looked down upon because they were at a bar or club, or had consumed alcohol.

Social Media

In cases such as the Steubenville rape case, where images and videos of the victim being assaulted were circulated through Facebook and texting, social media plays a huge role. YouTube personality and feminist speaker Laci Green thoroughly explains the phenomenon of rape culture in relation to the Steubenville case in this video on her channel “Sex +”. Rape culture is also exemplified in controversies surrounding the circulation of nude photos through social media. Women are called “sluts” and disrespected for taking nude photos. However, the photos in circulation are looked at without the permission of the owner of such photos. Private photos of women’s bodies being looked at and judged as public property has become extremely normal. This view of a women’s body as public property greatly contributes to a climate of rape culture.

Gender-based violence in video games

Society knows that video games are violent, sexist and objectifies women constantly. An extreme example would be Grand Theft Auto. Only females in this video game are touched, raped, and murdered. There are no female lead characters, instead, they are portrayed as prostitutes, fearful, and inferior. Some examples would be if a male character were to go to a strip club with prostitutes, having sexual intercourse would increase the player’s points for stamina. The male characters also try to grope women during lap dances while the guards are not watching. Running over women with cars, or following women on the street making them uncomfortable to speed walk and look over their shoulders is seen as an enjoyment during the game. It is only centered as males being dominant, it also encourages the players of the games to act violently and disrespectfully towards all female characters, which influences people in day to day lives to do the same.

University and College Campus

Rape culture has become especially noticeable on university and college campuses. Many recent rape cases on college campuses have been made increasingly prominent by the media. A prime example occurred in the publishing of a document by a male student from Dartmouth University. The document is titled “rape guide” and details how a female student could be persuaded to have sex. She was assaulted at a fraternity party shortly afterward.[14] Many male university students believe sexual conquests, under duress or otherwise, are something to brag about, rather than be ashamed of. The attitudes on campus seem to be one of complacency towards sexual violence. A recent survey of Canadian University men gave the result that 60% would commit sexual assault if they would not get caught.[15] Rape victims have also shown a tendency to under-report assault, with less than 10% of victims reporting to authorities. This reluctance to report likely stems from the lack of action and discipline accused rapists receive. Women feel fearful that they will not be treated well by police or legal processes, and that they will be humiliated with no justice to validate their claim.[15]

Columbia Mattress Protest

An example of this occurred in September of this year. A senior student at Columbia University name Emma Sulkowicz reported being assaulted in her dorm room by another student she knew from class. When Sukowicz reported her assaulter to the university she was met with various levels of bureaucracy that ignored her pleas that the aggressor be expelled. This leniency towards the assaulter is a key feature of rape culture that allows sexual violence to continue unhindered. In protest, Sukowicz took to carrying a mattress around Columbia’s campus that she refused to put down until her assaulter was expelled.[16]

Reproductive Rights

Rape culture contributes to a climate where women who have been raped are told by “pro-life” groups that it is immoral to abort an unwanted child produced by an assaulter. This is an extension of rape culture, and the idea that what a woman does with her body is not entirely her own choice. Too force women to bear a child created in rape strips her of dignity, and may trigger stress to be reminded of her assault.

The Handmaid's Tale

Margaret Atwood’s "The Handmaid’s Tale" provides an interesting picture of what rape culture might look like at its very extreme. In the novel, every pregnancy is created through the rape of the Handmaids. Each Handmaid’s body is no longer her property but the property of the totalitarian state of Gilead . Therefore, it is considered acceptable and applauded to violate Handmaid’s bodies in order to produce children.[17] Interestingly, the violation of a Handmaid is not considered rape because she does not have ownership of her body any longer. The state of Gilead aims to control women’s sexuality. This parallels the aim of rape culture: to dominate and control a woman’s sexuality and body.

Intersectionality

Intersectionality was coined in 1989 by feminist Kimberlé Krenshaw. The term has now become a central concept is feminist and sociological studies. It refers to when factors such as gender, sexual orientation, race, disability etc "intersect" to emphasize and cause increased structural inequality. [18] Rape culture is especially detrimental to those affected by intersectionality. There is a long history of sexual violence against minority groups, used to oppress and control the population. Around the time of the United States Civil war a pervasive stereotype of black women as "loose" and "immoral" was widely circulated and believed. Because of this stereotype, rapes of black women- especially by white men- went largely unpunished. Black women were thought of as highly promiscuous, and therefore asking to be sexually violated with or without their permission [19]. Black men were also affected. In the 1950's and 60's especially, innocent black men were lynched in huge numbers. In order to justify these horrific murders, the myth of the black man as a serial rapist of white women was circulated and widely believed.[20] In this way, many innocent black men and women were victimized and brutalized by rape culture. First Nations people were also victims of sexual violence. Colonizers used sexual aggression and violence as a tool to oppress Indigenous people and maintain their patriarchal society. [21] Today, women that also belong to another oppressed group are the most victimized by rape culture. Intersectionality has long historical roots, with only two cases of historical oppression touched on here, there are countless other cases of early rape culture around the globe.

Aboriginal Women in Canada

Aboriginal Women in Canada face extreme sexual violence as a result of early colonization. This group of women is perceived to be sexually deviant and is highly discriminated against. Degraded by the term “Dirty Squaw”, Aboriginal women are often viewed as property, just as Canadian land was viewed by early European settlers. Due to the fact that “aboriginal women aged fifteen or older are three and a half times more likely to be victims of violence than non-Aboriginal women” rights [22], this group makes up the majority of the missing women and murdered women cases from throughout Canada. In Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, an area home to one of the largest proportions of Aboriginal people in the country, hundreds of raped and murdered women have been taken. In memoriam, a march takes place on every Valentine’s Day through the streets [23] [24].

Much of the sexual violence targeted at this group of women stems from colonial settler’s perceptions of Native women. Upon arrival, European men viewed the Aboriginal women as pure and untouched, just as they viewed the land they were conquering. The women were highly sexualized, however, regarded as clean “Indian Princesses” [25]. In later years, their perception of the women negatively shifted, viewing them as “Dirty Squaws” who needed to be forced into submission and used for resources, just as they now viewed the land [26]. By regarding the women as useless, the victimization towards them became less important. Since the women were now seen to be sexually deviant and “dirty”, it was more acceptable for them to be the subjects of sexual violence. Herein lives the development of a rape culture towards Aboriginal women that was somewhat accepted by others[27].

The Effects of Rape Culture

The impact of rape culture and the notion of rape, in general, are associated with both physical and psychological effects that can be severely detrimental to an individual’s overall well-being. After an individual’s personal autonomy over their body has been stripped from them and they experience an incident of rape or sexual objectification or abuse, both immediate and long lasting effects result and in turn, contribute to how that individual functions in their daily lives and within society.

Psychological Impact

Not surprisingly, after a rape incident victims often show increased levels of distress and upset during the initial first week[28]. However, what is more alarming is that these levels of anguish and grief continue to persist for longer than a few weeks, a few months, and a few years; they essentially become relentless, lifelong effects that severely hinder a victim’s overall functioning and mental state. Approximately ¼ of women who are several years beyond their sexual assault or rape incident experience prolonged negative effects[29]. Victims of rape and sexual assault are more likely to experience major depression, drug abuse, alcohol dependence, generalized anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)[30]. Due to the brutal nature of rape and the complete lack of respect and regard for the victim during and following the rape and/or sexual abuse, the preceding effects seem almost inevitable. Moreover, the fact that rape challenges and partially destroys personal belief systems of safety, power or efficacy, trust, self-esteem, as well as intimacy adds to the increased negative psychological impact and augmented prevalence of mental health issues following incidences of rape and/or sexual abuse[31]. In a study of thirty-five rape victims who had been assaulted 2-46 years prior were interviewed and compared to non-victims in order to assess the long-term effects of sexual assault. The study showed that rape victims were found to be significantly more depressed, generally anxious and fearful than those who had not suffered any form of sexual abuse[32]. Another study measuring the same thing noted negative disturbances in the victims with regards to the following: self-esteem, sexual reputation, self-perceived value as a romantic partner, self-perceived attractiveness, work and social life, and health[33].

Physical Impact

Although, the physical impact of sexual abuse arguably may not be as persistent and long lasting as psychological trauma, the physical effects of sexual abuse are also important to uncover. Cuts, bruises, sexually transmitted diseases, unwanted pregnancies, and genital injuries are all quite common following rape and/or sexual abuse. Sexually transmitted diseases typically occur in 4% to 30% of rape victims[34]. A number of other conditions are also diagnosed at a higher rate amongst rape victims than non-victims, these include chronic pelvic pain, gastrointestinal disorders, headaches, seizures, and severe premenstrual symptoms[35]. Despite this, it has been said that approximately between one half and two-thirds of rape and sexual assault victims flee their horrific ordeals without any sign of physical trauma[36].

Consensual Sex

Sexualized violence occurs when consent is not firmly stated. There are many things which affect consent, for example, substances such as alcohol and drugs. If a person is under the influence of any substance, then their consent cannot legally be given. In order for consent to be substantial, you need to be mentally and physically capable. Diminished capacity - such as someone who is unconscious or on drugs may not have the legal ability to agree to have sex.

See also

References

- ↑ Women against Violence against Women rape crisis centre. (2014). "What is Rape culture?" http://www.wavaw.ca/what-is-rape-culture

- ↑ Buchwald, E., Fletcher, P. & Roth, M. (1994) "Transforming a Rape Culture."

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Ontario Women’s Directorate. (2014). Statistics: Sexual violence. Retrieved from http://www.women.gov.on.ca/owd/docs/sexual_violence.pdf

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Sexual Assault Support Centre. (n.d.). Myths and facts. Retrieved from http://www.gotconsent.ca/myths-and-facts.html

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Women Against Violence Against Women. (n.d.). Rape myths. Retrieved from http://www.wavaw.ca/mythbusting/rape-myths/

- ↑ Niemi, L. & Young, L. (2014). "Blaming the Victim in the Case of Rape." Psychological Inquiry: An International Journal for the Advancement of Psychological Theory, 25(2), 230-233.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Schmitt, F. (2008). "Rape." In V. Parrillo (Ed.), Encyclopedia of social problems. (pp. 749-751). Thousand Oaks, CA

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Amy Grubb, & Emily Turner. (2012). Attribution of blame in rape cases: A review of the impact of rape myth acceptance, gender role conformity and substance use on victim blaming. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(5), 443. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2012.06.002

- ↑ Rape Crisis England & Wales. (n.d.). Common myths about rape. Retrieved from http://www.rapecrisis.org.uk/commonmyths2.php

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Frohmann, L. (1991). Discrediting victims' allegations of sexual assault: Prosecutorial accounts of case rejections. Social Problems, 38(2), 213-226. doi:10.1525/sp.1991.38.2.03a00070

- ↑ Thicke, R., & Williams, P. (2013). Star Trak, LLC

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Pearson, A. (2000). "Rape Culture: It's all around us." Off our Backs, 30(3), 12-14.

- ↑ Green, D. (2013). "15 Recent Ads That Glorify Sexual Violence Against Women." Business Insider. http://www.businessinsider.com/sex-violence-against-women-ads-2013-5?op=1

- ↑ Douglas, Susan. (2014). "Rape Culture Reality Check: How can we tell if we have a 'rape culture'? In These Times. http://inthesetimes.com/article/16776/rape_culture_reality_check

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Canadian Federation of Students-Ontario. (2013). "Sexual Violence on Campus: The Gendering of Sexual Violence." Fact Sheet. http://cfsontario.ca/downloads/CFS_factsheet_antiviolence.pdf

- ↑ Kim, E. (2014). "Columbia Student carrying mattress to protest alleged rape gets 'overwhelmingly positive' response." Today News. http://www.today.com/news/columbia-student-protesting-sex-assault-mattress-response-overwhelmingly-positive-1D80129390

- ↑ Latimer, H. (2009). "Popular culture and Reproductive Politics: Juno, Knocked Up and the enduring legacy of The Handmaid's Tale." Feminist Theory, 10(2), 211-226

- ↑ http://knowledge.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/view/multicultural-america/n471.xml

- ↑ Davis, A. Rape, Racism, and the myth of the Black Rapist. http://www.rapereliefshelter.bc.ca/sites/default/files/imce/Rape,%20Racism%20%26%20Myth%20of%20Black%20Rapist_A%20Davis.pdf

- ↑ Davis, A. Rape, Racism, and the myth of the Black Rapist. http://www.rapereliefshelter.bc.ca/sites/default/files/imce/Rape,%20Racism%20%26%20Myth%20of%20Black%20Rapist_A%20Davis.pdf

- ↑ Smith, A. Conquest: Sexual Violence and American Indian genocide. Cambridge, MA: south end press, 2005.

- ↑ Anderson, A. (n.d.). Violence against Aboriginal women. Retrieved from http://inequalitygaps.org/first-takes/racism-in-canada/violence-against-aboriginal-women/.

- ↑ Culhane, D. (2003). Their spirits live within us: Aboriginal women in Downtown Eastside Vancouver emerging into visibility. The American Indian Quarterly, 27(2), 593-606.

- ↑ Feb 14th Annual Womens Memorial March. Retreieved from https://womensmemorialmarch.wordpress.com/about/

- ↑ Hanson, E. Marginalization of Aboriginal Women. (n.d.). Indigenous Foundations. Retrieved from http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/home/community-politics/marginalization-of-aboriginal-women.html

- ↑ MacIntosh, L. (2015). From Indian Princess to Dirty Squaw. GRSJ 224 99A Week 7 Power Point. Retrieved from https://connect.ubc.ca/bbcswebdav/pid-3010445-dt-content-rid-13373832_1/courses/SIS.UBC.GRSJ.224A.99A.2015WA.55299/Content/week_7_and_8/lecture_notes/wk_7_26.html

- ↑ Anderson, K. (2013). The Construction of a Negative Identity. Gender and Women's Studies in Canada: Critical Terrain, 269.

- ↑ Koss, M. (1993). Rape: Scope, impact, interventions, and public policy responses. American Psychological Association, 48(10), 1062-1069

- ↑ Koss, M. (1993). Rape: Scope, impact, interventions, and public policy responses. American Psychological Association, 48(10), 1062-1069

- ↑ Koss, M. (1993). Rape: Scope, impact, interventions, and public policy responses. American Psychological Association, 48(10), 1062-1069

- ↑ Koss, M. (1993). Rape: Scope, impact, interventions, and public policy responses. American Psychological Association, 48(10), 1062-1069

- ↑ Santiago, J., McCall-Perex, F., Gorvey, M., & Beigel, A. (1985). American Journal of Psychiatry, 142:13380-1340

- ↑ Perilloux, C., Duntley, J. & Buss, D. (2011). The Costs of Rape. Archive of Sex Behaviour, 41: 1099- 1106

- ↑ Koss, M. (1993). Rape: Scope, impact, interventions, and public policy responses. American Psychological Association, 48(10), 1062-1069

- ↑ Koss, M. (1993). Rape: Scope, impact, interventions, and public policy responses. American Psychological Association, 48(10), 1062-1069

- ↑ Koss, M. (1993). Rape: Scope, impact, interventions, and public policy responses. American Psychological Association, 48(10), 1062-1069

<Wgac.colostate.edu,. 'Street Harassment - Women And Gender Advocacy Center'. N.p., 2015. Web. 18 Nov. 2015./> <Stoprelationshipabuse.org,. 'Rape Culture « Center For Relationship Abuse Awareness'. N.p., 2015. Web. 10 Nov. 2015./> <Papadaki, Evangelia (Lina). 'Feminist Perspectives On Objectification'. Plato.stanford.edu. N.p., 2010. Web. 21 Nov. 2015.> <Well.wvu.edu,. 'Rape Myths And Facts | Wellwvu | West Virginia University'. N.p., 2015. Web. 21 Nov. 2015.>