Learning Commons:Content/Learning Challenges/Studying

The Problem

I'm studying hard and it's not working. Though putting lots of time into studying can make it feel like you are learning a lot, the fact is that studying must be effective rather than lengthy to be useful. Studying for hours every day will make you feel like you've accomplished something, but if the information you are learning cannot be quickly and easily put into practice, then you need to re-asses your study methods. Many of our ideas about studying actually negatively impact our learning, such as:

Learning is fast

When we are learning something new by re-reading and highlighting (rather than self testing and solving problems), our brains often fool us into thinking that we are learning. This is called a fluency or familiarity bias and it happens when we think that something familiar and clearly explained has actually been learned. In fact, the best way to test whether you know something is to try to teach it to someone else - this will help you clarify your gaps in understanding.

Memorizing the facts is what's important

At university, what's important is your understanding of concepts and ideas, when to apply them and how and in what circumstances they are useful. This sort of understanding is enhanced when you look for the connections between concepts and ask yourself questions about what you are reading so that you can extract meaning.

Talent is everything. If I'm not talented in a subject - I can't expect to do well.

Talent can help, but your attitude about learning is way more important. If you believe your learning abilities are fixed, you'll put up mental blocks that hinder your learning. For example, if you are used to getting straight A's you may tend to avoid risks that might take you out of your comfort zone and risk your perfect record. Conversely, if you believe you are not good at something (say math for example) you may lower your expectations,etc. Either way, those fixed beliefs will prevent you from opening up to new experiences that may have a profound impact on your learning. Students who have a 'growth mindset' about learning, and believe that they can really improve over time and with effort tend to take more chances, progress faster, and see risk and failure as part of the learning process (Dweck, 2006). See Myth #1 below for more information and resources.

It's fine to multi-task while studying

Though we all believe that we multi-task well, the truth is we don't. Every distraction we have when studying decreases the amount we are able to learn, and increases the time we must devote to studying. We are especially bad at multi-tasking when one task involves concentration and effort, meaning that studying is best done with extreme focus and minimal distractions.

I'm a good judge of my own learning.

Research tells us that we are not very good at assessing our own learning. We tend to overestimate or underestimate our own abilities. This is known as the Dunning-Kruger effect, a well documented cognitive bias. According to Steven Novella (in his article about the Dunning-Kruger effect): "the most competent individuals tend to underestimate their relative ability a little, but for most people (the bottom 75%) they increasingly overestimate their ability, and everyone thinks they are above average."

The Myths

The following myths about learning are relevant to the challenge of studying.

Myth 2: I only need one good method for studying.

Sometimes, study methods that worked in high school - just don't serve you well in university. If your tried and true study strategies aren't working, use a different approach. Monitor your learning, by measuring your knowledge against what you expect. Before you start studying, guess how it'll go. Predict your homework and test results, and see if you're accurate or not. Notice when your expectations fall short of (or overshoot) reality, and adjust your approach accordingly. This is called metacognition, and it's an important part of effective learning.

There's also some evidence to suggest that mixing it up (in terms of where, when and how we study and learn) promotes recall (Carey, 2015)

|

Myth 3: If it's easy, I must be learning.

Often, we are fooled into thinking we understand something, because terms or concepts sound familiar. You might find yourself feeling like you really understand the material, when your brain is really just responding to the fact that it's seen this exact material before. To add to that, if it is presented in a clear and pleasing manner, it might create an illusion of fluency. This is called a fluency bias or familiarity trap—when everything seems familiar, your brain doesn't have to work so hard, so it feels like you've mastered the material, even though you haven't. Try to mix things up as you're studying.

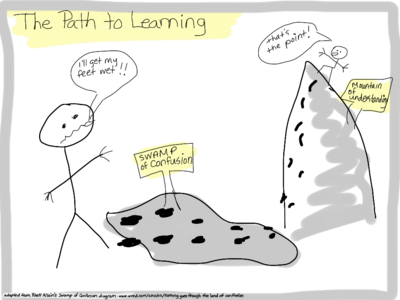

More and more, evidence suggests confusion is where deep learning lies. It might even be that some level of confusion activates parts of your brain which regulate learning and motivation, helping you achieve a greater level of understanding. If you're not confused, you might not be learning. See Learning Goes Through the Land of Confusion by Rhett Alan, a physics professor at Southern Louisiana University, for a brief explanation. Don't let yourself get discouraged if it feels like you aren't 'getting it': that's a good sign.

Other science educators have found support for the idea that confusion is important to learning. Eric Mazur, a Harvard physics education researcher, has done some interesting research on the topic—a summary of his findings can be found in this blog post. Another researcher and science educator, Derek Muller, has looked at the relationship between learning and video. Watch this video where he explains his findings and talks about the strengths and weaknesses of Khan Academy.

|

The Strategies

Take steps to 'build effective study strategies

Aim for understanding (vs. surface knowledge)

|

The Toolkits

Check out some of our student toolkits to support your learning:

The Links

- Optimizing Learning in College: Tips from Cognitive Psychology

- Psych Central: 10 Highly Effective Study Habits

- University of Guelph: Learning How to Study

Videos:

- College Info Geek: Study Less Study Smart

- College Info Geek: How to Study Effectively: 8 Advanced Tips

- College Info Geek: Exam Tips: How to Study for Finals

Health and Wellness at UBC: