LFS:SoilWeb/Soil Classification/Factors of Soil Formation

Soils are natural expressions of the environment in which they were formed. They are derived from an infinite variety of materials that have been subjected to a wide spectrum of climatic conditions. Soil development is influenced by the type of rocks and topography on which soils occur, the plant and animal life which they support and the amount of time that they have been exposed to these conditions.

Soil forms as a result of five soil formation factors. Differences in soil type within and between regions are a result of the interactions between these factors.

- Parent material: Unconsolidated material in which soil development occurs.

- Climate: In particular, precipitation and temperature.

- Biota: Living organisms including vegetation, microbes, soil animals, and human beings.

- Topography: Slope, aspect and elevation.

- Time: Period that parent materials are subjected to soil formation.

Soil formation in action. A rock is being weathered under the influence of physical, chemical and biological factors and, given enough time, it will be transformed into a soil (Photo: Dr. M. Krzic, UBC).

| RELATED LINK:

To learn more about soil formation factors, visit the VSSLR's Soil Formation and Parent Material website. |

1. Parent Material

Parent material is the material from which a soil forms. It consists of unconsolidated and more or less chemically weathered mineral or organic material.

Colluvium type of parent material (Photo: Dr. M. Krzic, UBC)

The nature of the parent material influences both the texture and mineral composition of the soil. Soil parent material consists of rocks, which can be classified as:

- Residual or sedentary: Sediments developed in place (in situ) from underlying rock over a long period of intense weathering.

- Cumulose: Organic deposits developed in place from plant residues that have been preserved by a high water table, or some other factor that inhibits decomposition. Examples are peat (undecomposed or slightly decomposed organic matter) and muck (highly decomposed organic matter).

- Transported: Loose sediments or surficial materials that were transported and deposited by gravity, water, ice or wind. The following table lists transported parent materials and their modes of deposition.

| Mode of Deposition | Resulting Parent Material |

|---|---|

| Water |

|

| Water and Ice |

|

| Ice |

|

| Wind | |

| Gravity |

2. Climate

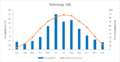

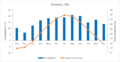

Climate determines the nature (physical, chemical or biological) and rate of weathering (that acts on parent material to form soil). The most important elements of climate for soil formation are precipitation and temperature. For example, the amount of precipitation determines the extent of leaching through a soil profile and seasonal temperature fluctuations influence the number and rate of chemical reactions and overall biological activity.

Graphs showing average temperature and precipitation normals for Canadian cities (1971-2000, Environment Canada data).

-

Vancouver, BC

-

Winnipeg, MB

-

Toronto, ON

-

Charlottetown, PEI

-

St. John's, NL

-

Whitehorse, YT

3. Biota

Living organisms, including plants, microbes, soil animals, and humans, are collectively referred to as biota. Soil development is affected by both the type and number of organisms that live in and on the soil. Plants influence the amount of organic matter buildup in the soil. For example, soil developed under grassland vegetation has organic matter incorporated into the rooting zone, while in forest soils organic matter accumulates on the surface.

Another example of how plants affect soil formation is shown in the photo below. Plant roots will start growing through cracks in rocks where some dust has accumulated. Over the years, roots will widen the cracks, enhancing rock weathering and subsequently soil formation.

Plants can enhance soil formation by disintegrating rocks (Photo: Dr. P. Cumming, UBC)

Human activity also influences soil formation. Destruction of natural vegetation by changing the frequency and extent of natural fires or by soil tillage abruptly modifies the soil formation factors. These changes have influenced the relative distribution of forests and grasslands in many areas of British Columbia.

The below image illustrates an example of human impacts on soil formation: The Dust Bowl on the Great Plains during the 1930s.

4. Topography

There is a strong interaction between topography and vegetation, which influences soil formation. The photo below (taken in Nicola Valley in the southern interior of BC) illustrates the distribution of grasses and trees within a grassland ecosystem. Trees occupy slight depressions where soil moisture accumulates, resulting in a different soil type than in adjacent upland areas dominated by grasses.

Topography impacts soil moisture, which in turn impacts the distrubition of grasses and trees and their associated soil types across the landscape (Photo: Dr. M. Krzic, UBC).

Slope influences

- the relative rate of water infiltration into the soil,

- surface runoff and its associated soil erosion, and

- distribution of vegetation.

Aspect influences the angle at which the sun's rays strike the Earth's surface. Slope and aspect together influence soil temperature, soil water content and vegetation, which in turn affects soil formation. For example, in the Northern Hemisphere, cooler north-facing slopes are usually forested with slower soil development than on warmer south-facing grasslands. Consequently, a north-facing slope has a thinner soil than a south-facing slope on the same ridge.

Elevation influences vegetation and soil type. In the interior of British Columbia, climate becomes cooler and more wet as elevation increases from valley bottoms to mountain tops. Such climate gradients are usually reflected in a shift from grassland to forest and alpine plant communities.

As elevation increases, so does the soil moisture consequently allowing trees to establish and replace grasses, which dominate the lower elevations. (Photo: Dr. M. Krzic, UBC).

5. Time

Soil formation is a slow process that takes hundreds or even thousands of years. A younger soil will reflect characteristics of the parent material better than an older soil, since insufficient time has elapsed to permit significant development. Canadian soils, including British Columbia's, are relatively young when compared to soils of the southern United States, as they have only been developing since the recession of the last ice age ~10,000 years ago.

The animation shown here illustrates retreat of glaciers that covered parts of North America about 18,000 years ago and which started to retreat about 10,000 years ago.

The retreating Athabasca Glacier in the Columbia Icefields, Alberta, Canada (Photo: Dr. S. Grand, UBC).

Interactions of Soil Formation Factors

The formation of soil is a complex process, and the five soil formation factors are active simultaneously and interdependently. Individual factors are of interest because they help us simplify and explain soil formation. They are particularly useful for soil surveying and mapping, since soils are stratified on the basis of individual formation factors.