GRSJ224/femvertising

Femvertising, also known as ad-her-tising or feminist advertising, refers to “female-targeted advertising that exhibits qualities of empowering women, feminism, female activism, or women leadership and equality.”[1] With feminism’s growing presence in pop culture, companies have increasingly turned to advertising strategies that use feminist imagery and messages in order to promote sales of products and services, as well as company branding.

Feminism can be referred to as “the theory of the political, economic, and social equality of the sexes.”[2] While femvertising promotes gender equality, definitionally speaking and in principle, it has been criticized for appropriating themes of empowerment in order to lure a powerful consumer group into consumption. Many scholars argue that femvertising messages contain an inherent conflict between its function as carriers of individual consumption and feminism’s intrinsically political and social causes.[3]

Purpose of Advertising

The primary task of an advertisement is to influence consumers’ purchasing decisions and perceptions of a particular product, service or brand. Advertising messages that embed the cultural values and norms of particular consumer groups will have greater success than those that do not, primarily because of a higher consumer acceptance.[4] Thus, one scholar argues, advertising “often reflects the concerns, anxieties, dreams and aspirations of society.”[5]

Feminism in Advertising

Over the past century, consumerism habits have been dominated by females. One study found that 80% or more of day-to-day household purchases are by women.[6] Thus, females have historically been - and remain today - a primary target of ad agencies.

Marketers have latched on to societal trends and incorporated social justice into new advertising campaigns. This has given rise to “commodity activism,” or, “a process by which social action is increasingly understood through the ways it is mapped onto merchandising practices, market incentives, and corporate profits.”[7] One study found that with comparable price and quality, 91% of global consumers are likely to switch to a brand associated with a good cause.[8] Femvertising can be considered a vein of commodity activism because the feminist movement is ultimately used as a mechanism to sell products to women. SheKnows Media defined femvertising as “advertising that employs pro-female talent, messages, and imagery to empower women and girls,” and has since updated that definition to include advertisements that “do the right thing by ALL humans, regardless of gender, race, religious beliefs and sexual orientation.”[9]

Examples of Femvertising

Femvertising campaigns attempt to build a relationship with females through depictions of “real” and “ordinary” women by highlighting their unique and personal experiences. This approach to advertising has been proven to have positive influences on product sales and company reputation.

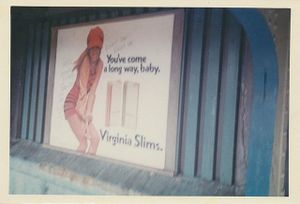

Virginia Slims

Virginia Slims is a cigarette brand developed by Philip Morris in 1968.[10] It was marketed exclusively to women using advertising campaigns that exploited the civil rights movements of the 1960s. By presenting strong, independent and liberating women in their advertisements, and using seemingly empowering slogans, the brand was able to use feminism as a key mechanism to improve sales and establish themselves in a competitive market. Slogans included “You’ve come a long way, baby” (1960s - 1980s), “It’s a woman thing” (1990s) and “Find Your Voice” (2000s).[11]

Always’ Like A Girl Campaign

Launched in 2013, Procter & Gamble's #LikeAGirl campaign made a blatant effort to highlight female confidence and strength through advertisements for feminine hygiene products. The goal was to change negative perceptions of female activities and abilities by featuring young women doing things ‘like a girl,’ including strenuous physical activity.[12] After watching one #LikeAGirl video, 76% of US girls between 16 to 24 said that they no longer view "like a girl" as an insult, and 8 out of 10 women (81%) said the video could change the way people think of the stereotypes surrounding women's physical abilities.[13]

Dove Campaign for Real Beauty

Launched in 2004, Dove’s “Campaign for Real Beauty” was a corporate, multimillion dollar, multimedia marketing campaign that “claims to oppose restrictive feminine beauty standards and promote a more democratic vision of beauty.[14] The idea behind the campaign was to show that women of all shapes and sizes should feel comfortable in their own skin. The campaigns selected ‘real women,’ rather than professional models to feature their new line of skin firming products. Ads featured multi-racial, wrinkled, freckled, and pregnant, women with different body types. The campaign was a commercial success and was endorsed by celebrities, gender scholars and professional associations.[15] It has also raised millions of dollars for eating disorder organizations and self-esteem programs.[16]

Criticism

Beauty Ideology

Some scholars argue that corporations are key actors in the production and reproduction of the beauty ideology. While such advertising campaigns are commended by some for their partial disruption of narrow Western beauty ideals, advertisers of cosmetic products are often criticized for putting an “inordinate amount of emphasis on the personal appearance of women.”[17] The beauty industry has been criticized for perpetuating and institutionalizing gender equality by “(re)producing largely attainable aesthetic standards and perpetuating misogynist and harmful cultural practices” such as cosmetic surgery.[18]

Gender Stereotyping

Femvertising “reflects long standing gender hierarchies that praise women for not for their brains, wit, work ethic, athleticism, or resilience, but predominantly for their appearance.”[19] For example, the Dove Campaign for Real Beauty’s empowering message of self-love still centres around personal appearance rather than other qualities and abilities of ‘real’ women.

Failure to Address Intersectionality

Some ‘feminist’ advertisements have been criticized for their failure to equally challenge the naturalization of women’s subordinate status as it intersects with inequalities of class, race and ethnicity. For instance, Pepsi's "Live Now Campaign" received backlash for its commodification of the Black Lives Matter Movement and glazing over of racial violence and minority voices.[20][21]

Consumption

Femvertising has received criticism for their implication that feminist ideals can be expressed and achieved via consumption. Some scholars argue that femvertising directly contradicts feminism because women’s empowerment is not simply a matter of money and purchasing choices, but also the existence and enforcement of social policies and practices.

Implications for Feminism

There is much debate surrounding companies’ commitment to women’s equality and empowerment. Some scholars argue that femvertising messages promote gender equality, and thus are feminist.[22] Others see femvertising as a resource or political tool to spread feminist messages through online sharing and engagement.[23] These digital advertisements can be considered “carriers of a lightly packed feminism that could be easily absorbed by almost everyone.”[24]

Contrarily, some scholars see these advertisements as a ‘facade’ of feminism that is ineffective against institutionalized gender inequality. One scholar describes femvertising as a “simple scam to lure a powerful consumer group into consumption.”[25] Others argue that it lacks political force, and allows women to "wear an identity associated with self-respect, independence and personal strength, and collective identity and community without doing any of the hard consciousness-raising work usually required to produce collective transformation.”[26] Some scholars insist that femvertising ultimately “contributes to disarming the feminist movement and preventing further feminist advances.”[27]

References

- ↑ Baxter, A. (2015). Faux Activism in Recent Female-Empowering Advertising. The Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, 6(1), 48-58. Retrieved from https://www.elon.edu/docs/e-web/academics/communications/research/vol6no1/05BaxterEJSpring15.pdf.

- ↑ Mirriam-Webster. (n.d.). Feminism. Retrieved October 12, 2017, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/feminism

- ↑ Abitbol, A. & Sternadori. (2016). You Act Like a Girl: An examination of consumer perceptions of femvertising. Quarterly Review of Business Disciplines, 3(2), 117-138. Retrieved from http://iabdnet.org/QRBD/Volume%203/QRBD%20Aug%2016.pdf#page=45

- ↑ Gunaratne, A. (2000). The influence of culture and product consumption purpose on advertising effectiveness. In A. O’Cass (Ed.). Proceedings of ANZMAC 2000. (pp. 443-47). Gold Coast, Australia: Australian & New Zealand Marketing Academy. Available from http://anzmac.info/conference/2000

- ↑ Stammerjohan, C., Wood, C., Chang, Y., & Thorson, E. (2013). An empirical investigation of the interaction between publicity, advertising, and previous brand attitudes and knowledge. Journal of Advertising (34)4 pp. 55-67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2005.10639209

- ↑ Baxter, A. (2015). Faux Activism in Recent Female-Empowering Advertising. The Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, 6(1), 48-58. Retrieved from https://www.elon.edu/docs/e-web/academics/communications/research/vol6no1/05BaxterEJSpring15.pdf.

- ↑ Baxter, A. (2015). Faux Activism in Recent Female-Empowering Advertising. The Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, 6(1), 48-58. Retrieved from https://www.elon.edu/docs/e-web/academics/communications/research/vol6no1/05BaxterEJSpring15.pdf.

- ↑ “Statistics Every Cause Marketer Should Know.” Cause Marketing Forum. Web. 6 Nov. 2014.

- ↑ Joskowitz, L. (2017). The Winners of the 2017 #Femvertising Awards Are In. SheKnows Media. Retrieved from http://www.sheknows.com/entertainment/articles/1136262/femvertising-award-winners-2017

- ↑ Abitbol, A. & Sternadori. (2016). You Act Like a Girl: An examination of consumer perceptions of femvertising. Quarterly Review of Business Disciplines, 3(2), 117-138. Retrieved from http://iabdnet.org/QRBD/Volume%203/QRBD%20Aug%2016.pdf#page=45

- ↑ Baxter, A. (2015). Faux Activism in Recent Female-Empowering Advertising. The Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, 6(1), 48-58. Retrieved from https://www.elon.edu/docs/e-web/academics/communications/research/vol6no1/05BaxterEJSpring15.pdf.

- ↑ Hobbs, T. (2015). Procter & Gamble confident Always’ ‘Like A Girl’ campaign has legs. Marketing Week (Online); London: Centaur Communications Ltd. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1660197662?accountid=14656

- ↑ Dandad.org. (2015). Always like a girl campaign case study insights. London. Retrieved from https://www.dandad.org/en/d-ad-always-like-a-girl-campaign-case-study-insights/

- ↑ Johnston J. & Taylor. J (2008). Feminist Consumerism and Fat Activists: A Comparative Study of Grassroots Activism and the Dove Real Beauty Campaign. Signs, 33(4), 941-966. DOI: 10.1086/528849

- ↑ Stampler, L. (2013). How Dove's 'Real Beauty Sketches' became the most viral video ad of all time. Business Insider. Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com/how-doves-real-beauty-sketches-became-the-most-viral-ad-video-of-all-time-2013-5

- ↑ Johnston J. & Taylor. J (2008). Feminist Consumerism and Fat Activists: A Comparative Study of Grassroots Activism and the Dove Real Beauty Campaign. Signs, 33(4), 941-966. DOI: 10.1086/528849

- ↑ Johnston J. & Taylor. J (2008). Feminist Consumerism and Fat Activists: A Comparative Study of Grassroots Activism and the Dove Real Beauty Campaign. Signs, 33(4), 941-966. DOI: 10.1086/528849

- ↑ Johnston J. & Taylor. J (2008). Feminist Consumerism and Fat Activists: A Comparative Study of Grassroots Activism and the Dove Real Beauty Campaign. Signs, 33(4), 941-966. DOI: 10.1086/528849

- ↑ Abitbol, A. & Sternadori. (2016). You Act Like a Girl: An examination of consumer perceptions of femvertising. Quarterly Review of Business Disciplines, 3(2), 117-138. Retrieved from http://iabdnet.org/QRBD/Volume%203/QRBD%20Aug%2016.pdf#page=45

- ↑ Newstex. (Aptil 20, 2017). Cantech Letter: How it all went wrong: UBC prof breaks down Pepsi’s Kendall Jenner ad. Weblog post. Newstex Finance & Accounting Blogs, Chatham: Newstex.

- ↑ Monahan, E. (April, 2017). Actual Empowerment Doesn’t Matter You Can Buy it at an REI Near You. Terra Incognita Media. Retrieved October 10, 2017, from http://www.terraincognitamedia.com/features/actual-empowerment-doesnt-matter-you-can-buy-it-at-an-rei-near-you2017

- ↑ Love, M., & Helmbrecht, B. (2007). Teaching the conflicts: (Re)engaging students with feminism in a postfeminist world. Feminist Teacher (18)1 (pp.41-58). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.calpoly.edu/engl_fac/7/

- ↑ Cochrane, K. (2013). All the Rebel Women: The rise of the fourth wave of feminism. (Guardian Shorts)

- ↑ Jalakas, L. D. (2016). The ambivalence of #femvertising. Msc Media and Communication Thesis. Retrieved from http://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=8872529&fileOId=8881266

- ↑ Jalakas, L. D. (2016). The ambivalence of #femvertising. Msc Media and Communication Thesis. Retrieved from http://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=8872529&fileOId=8881266

- ↑ Johnston J. & Taylor. J (2008). Feminist Consumerism and Fat Activists: A Comparative Study of Grassroots Activism and the Dove Real Beauty Campaign. Signs, 33(4), 941-966. DOI: 10.1086/528849

- ↑ Angela McRobbie as quoted in Jalakas, L. D. (2016). The ambivalence of #femvertising. Msc Media and Communication Thesis. Retrieved from http://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=8872529&fileOId=8881266