Documentation:Supporting Critical Thinking Online/Learning Module

Introduction

Critical thinking is defined in a variety of ways in the educational literature. Sharon Balin et al (1999) offer a broad based and helpful conceptualization. They consider critical thinking as the application of "appropriate criteria and standards to what we or others say, do, or write". This view of critical thinking holds that intellectual resources must be acquired by critical thinkers over time - years, not months. These resources include appropriate background knowledge, an understanding of context specific standards, a repertoire of strategies for thinking about a problem or argument, and certain habits of mind. In the online environment, discussion forums offer an opportunity to think critically about and share perspectives on important themes, questions and ideas. Other approaches may include, collaborative group work, case based or problem based learning.

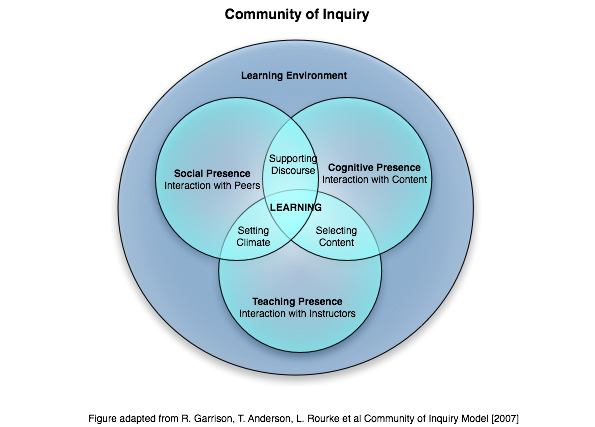

Instructors and facilitators play an important role in creating the learning environment and facilitating the social and communicative aspects of online learning. Garrison, Anderson, Rourke, et al (2007) incorporate this view in their Community of Inquiry Model. Xin & Feenberg (2006) point out that communication and intellectual engagement are “intertwined and inseparable” and together contribute to collaborative learning.

In this module, we examine the concept of critical thinking as it relates to ‘cognitive presence’, and consider ways in which online facilitators might promote critical thinking. We'll also consider the challenge of assessing critical thinking and learners’ work in online discussion forums, and examine the utility of assessment rubrics.

Learning Objectives

These objectives are at the level of beginning exploration.

At the end of this module, participants will be able to:

- identify various ways in which instructors can assist learners and promote critical thinking.

- identify challenges in assessing critical thinking and online discussion.

- access a useful resource in thinking about rubrics to support assessment in this area.

Readings

- Balin, et al (1999) Originally published in Journal of Curriculum Studies (1999) vol. 31, no. 3, 285±302 Conceptualizing Critical Thinking. Full Text pdf

- Case, Roland (2005) Originally published in Education Canada (Spring 2005) 45(2) 45-49 Moving Critical Thinking to the Main Stage. Full Text pdf

- Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T. & Archer, W. (2000). Critical Inquiry in a Text-based Environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2), 87-105.

- Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2001). Critical Thinking and Computer Conferencing:A Model and Tool to Assess Cognitive Presence. American Journal of Distance Education. [pdf Full Text]

- Mertler, Craig A. (2001). Designing scoring rubrics for your classroom. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, [1]. Retrieved April 22, 2009

- Xin, C. & Feenberg, A. (2006). Pedagogy in Cyberspace: The Dynamics of Online Discourse. Journal of Distance Education 21 (2):1-25

Links

- TechLearning: Blooms Taxonomy Blooms Digitally by Andrew Churches (2008)

- Critical Thinking Community of Practice at UBC Okanagan

- Videoclips from CriticalThinking.org

- Designing scoring rubrics for your classroom. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, Craig Mertler (Bowling Green State University)

- Resources for Learners on LEAP: Critical Thinking Toolkit

Media

Dr. Richard Paul defines the universal standards with which thinking may be "taken apart" evaluated and assessed. Excerpted from the Socratic Questioning Video Series from the Foundation for Critical Thinking.

Promoting Critical Thinking

Bailen et al (1999) point out that the teacher's role in promoting critical thinking is best conceptualized as "furthering the initiation of students into complex critical practices that embody value commitments and require the sensitive use of a variety of intellectual resources in the exercise of good judgement."(p.14) This doesn't mean the teaching of particular skills, but rather encouraging learners to develop a practice and habits of thinking that promote:

- formulation and articulation of clear questions and problems relevant to a context.

- gathering and interpreting relevant information using examples, analogies, metaphor and illustrations to illustrate meaning.

- conclusions and solutions that are well-reasoned and tested against relevant criteria and standards.

- open minded thinking that recognizes biases, assumptions, implications and practical consequences.

- effective communication with others in working through solutions to complex problems.

Taxonomies and Critical Thinking

In the context of college or university education, we are often looking to promote what some educators call ‘higher order learning’, which is often misconstrued as critical thinking. Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives is a widely respected approach to classifying higher order thinking skills and is often used as a basis for designing learning objectives. Recent updates to the taxonomy identify analysis, evaluation and creation as aspects of critical thinking we can promote. Yet, if we ascribe to the concept of critical thinking as a quality of thinking rather than higher or lower order cognitive task, then it becomes clear that learning tasks can be carried out in a critically thoughtful manner, just as they can be carried out in a rote, thoughtless manner - regardless of where those tasks sit in Bloom's hierarchy. This is a central point in Roland Case's Moving Critical Thinking to the Main Stage.

Recent focus on the development of digital competencies has led to some interesting work by Andrew Churches [2008]. He has categorized digital skills according to Bloom’s taxonomy, which may be very useful to instructors who are planning to incorporate new and emerging technologies into the curriculum.

"Whether or not students are thinking critically depends more on the qualities that characterize their thinking than on the specific nature or type of mental operation." (Case, 2005).

Criteria for Evaluating Content

Case suggests that teachers can engage students in thinking critically in any intellectual task involving judgment or choice among options by introducing them to criteria that they may use to evaluate the content in question. Such criteria may include attention to:

- Argument: A proposal/conclusion supported by a reason or reasons.

- Evidence: Information that supports an argument.

- Credibility: The believability of information as judged by further criteria including considerations of:

- neutrality/bias

- reputation

- corroboration

- consistency

- expertise

Intellectual Resources for Critical Thinking

According to Bailin et al (1999), there are five kinds of intellectual resources required for critical thinking. These are:

- Background knowledge: the depth of knowledge one has about a particular subject or area of practice will (to a large extent) affect his/her ability to think critically about it.

- Understanding of the standards of good thinking: these include standards that are relevant to judging intellectual products (such as arguments, theories, works of art) and guiding practices of deliberation or inquiry. These may involve evolving traditions of inquiry and criticism, appropriate to the field or practice under review.

- Knowledge of key critical concepts:this involves distinguishing among different kind of intellectual products (types of arguments or statements for example).

- Strategies for thinking: this may include counter-arguments, examining the consequences of a variety of actions and discussion with others considered more knowledgeable on a subject. The more specific the strategy is to the domain under study, the more powerful it will likely be in promoting critical thinking.

- Habits of mind: these are the personal committments, values and standards one has about the principles of good thinking. These may include: respect for reason and truth, respect for and appreciation of high-quality, an inquiring attitude, an open mind, a fair mind, an independent mind, respect for others in group inquiry, respect for legitimate intellectual authority and an intellectual work ethic.

Critical Thinking and Cognitive Presence

Garrison, Archer & Anderson (2001) propose a generalized model of practical inquiry which they feel reflects the critical thinking process and the means to create cognitive presence in the online environment.

Their focus is on the process and evidence of critical thinking within the group or community of inquiry. Anderson, Garrison and Archer also stress the importance of both the shared and private worlds of the learner as key to understanding how to create and support cognitive presence in an educational context.

In the diagram below, the private dimension reflects the continuum between action and deliberation. This may be where learners consider their prior experience, background knowledge and their strategies for thinking that they apply to think critically about the information presented to them. The public dimension represents the transition between the abstract and concrete. Another way to look at it might be the application of those habits of mind, values and attitudes about good thinking as they contribute their ideas and respond to the ideas presented by others.

The work of Randy Garrison and Terry Anderson highlights three essential and overlapping elements of an online learning environment in their Community of Inquiry Model: Cognitive Presence, Social Presence and Teaching Presence. It is the cognitive presence that is most closely tied to critical thinking.

In the Community of Inquiry model, cognitive presence describes learner participation in a process of “critical, practical inquiry”, in engaged collaboration with fellow learners. The instructor's role then, is to encourage and support discourse between students by designing activities which promote engagement with the subject and dialogue with each other; modelling and supporting the development of good facilitation skills through the use of good questions, clear communication and clarification regarding important concepts that are under analysis and thinking through an approach to assessment that focuses on the application of critical thinking in collaborative inquiry.

Garrison, Anderson and Archer's Model of Practical Inquiry offers a framework for helping us understand cognitive presence from the perspective of the learner and the processes engaged in while establishing that presence online.

Xin & Feenberg (2006) expand on this idea by proposing that the goals of cognitive presence, or “intellectual engagement” are:

- for individuals to acquire new concepts and achieve conceptual change

- for the group to achieve convergence

These two outcomes are connected: individuals achieve conceptual change through a collaborative “struggle for convergence” in which the group co-constructs new knowledge. In this case, convergence does not necessarily mean total agreement but rather a state of equilibrium - where individuals are enlightened by the discussion. The instructor's role is to provide leadership (perhaps in collaboration with other students) and moderate the discussion in such a way as to keep students motivated by engaging them in discussion and taking opportunities to clarify concepts and extend knowledge of the subject area without "lecturing". The figure below suggests one representation of these dynamics.

Reading Review

- Xin, C. & Feenberg, A. (2006). Pedagogy in Cyberspace: The Dynamics of Online Discourse. Journal of Distance Education 21 (2):1-25. Review pages 5-15.

- Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T. & Archer, W. (2000). inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2), 87-105. Review pages 98-99.

Learning Activities for Critical Thinking

Activities that support critical thinking might be described as:

- Assignments that challenge students socially and emotionally, that encourage the exchange of different perspectives, that require ideas be fully articulated and defended

- “instruction that stresses discussion, with an explicit emphasis on problem-solving procedures, may be effective in enhancing critical thinking.”

from: Teaching in an Online Environment:Group work for Critical Thinking

Online Discussion and Group work (designed around a problem or challenge) are a couple of options to look at.

Online Discussion

Asking Good Questions

Online discussion is based on good questions, whether these are proposed by students, by the instructor or (in some cases) both. "Deep questions drive our thought underneath the surface of things, force us to deal with complexity." Here are some examples of question types and the kind of thought they may stimulate: from: The Role of Questions in Teaching, Thinking and Learning

- questions of purpose: help us define tasks.

- questions of information: forces us to look at source and quality of our information.

- questions of interpretation: ask us to examine how we are organizing or assigning meaning to information.

- questions of assumption: encourage us to examine what we might be taking for granted.

- questions of implication force us to look at where our thinking is bound to end up.

- questions of point of view ask us to examine our own and others perpectives and what is behind those points of view.

In his article, The State of Critical Thinking Today (2004), Dr Richard Paul (Critical Thinking Foundation) suggests that learners can be encouraged to develop a practice of critical thinking about the questions they are presented with. He offers these suggestions:

- What is my purpose?

- What question am I trying to answer?

- What data or information do I need?

- What conclusions or inferences can I make (based on this information)?

- If I come to these conclusions, what will the implications and consequences be?

- What is the key concept (theory, principle, axiom) I am working with?

- What assumptions am I making?

- What is my point of view?

For more about designing good questions, see the Examples in Practice section.

Facilitating the Discussion

Effective facilitation is about online leadership. As Xin and Feenberg suggest,"the two-sidedness of moderating—social and cognitive—is the key to online pedagogy."(p.19) They offer a summary of moderating functions:

- Contextualizing Functions: opens discussions, sets the tone, selects themes or questions for discussion (or sets up a process for students to do this); refers to readings, resources or links to extend thinking.

- Monitoring Functions:recognizes contributions, prompts contribution by posing new questions to the group; assesses contributions.

- Meta Functions: addresses issues towards solving problems related to lack of clarity, information overload, etc.; maintains conditions required for good communication; weaves common threads between participant comments, offering prompts and summary when important; delegates others to role of weaver, summarizer.

Discussion resources for faculty:

- Creating the Online Learning Environment: Engaging Learners

Discussion resources for learners:

Group Work

In her presentation: Teaching in an Online Environment:Group work for Critical Thinking, deChambeau suggests that effective group work can promote critical thinking practice in the following ways:

- Working in peer groups makes the thinking process public. When thinking publicly students tend to spend more time working to express themselves clearly.

- If critical thinking is the intentional application of higher order skills such as analysis, synthesis, inference, evaluation, problem recognition and problem

solving, then appropriate exercises for groups can specifically enforce practice of these skills.

Tips for Effective Group Work

- Be very clear in describing the task and how it relates to the broader learning goals/ objectives you have identified.

- Use examples of good work from previous classes

- The issues students struggle with as a group can be complex, but the assignment itself should be simple

- Give enough lead time for students to test out the technology they will use to support their online group work.

- Consider ice breaker exercises for groups to build trust and camaraderie before starting an actual assignment

- Clarify your role in the process and make yourself available as a resource

- Consider using contracts and/or peer-evaluation mechanisms to support the work.

- Group work resources for learners: Groupwork Toolkit on LEAP

- Group work resources for faculty: Technology Enhanced Collaborative Groupwork- University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Assessment and Critical Thinking

Garrison et al. (2001) write:

Judging the quality of critical thinking as an outcome within a specific educational context is the responsibility of a teacher as the pedagogical and content expert. As a product, critical thinking is, perhaps, best judged through individual educational assignments. The difficulty of assessing critical thinking as a product is that it is a complex and (only indirectly) accessible cognitive process.

As facilitators, you will have responsibility for assessing your learners’ work, even if the grading scale in use is as simple as complete/incomplete. How should you start to think about ways of making sure your learners progress towards the learning goals you have for them? Assessment rubrics can make this task easier. A rubric is a scoring guide that describes criteria for student performance and differentiates among different levels of performance within those criteria. Because rubrics set forth specific criteria and define precise requirements for meeting those criteria they provide instructors and facilitators with an effective, objective method for evaluating skills that do not generally lend themselves to objective assessment methods.

Rubrics simplify assessment of student work and provide learners with an answer to the age-old "Why did you give it this grade?" question. At their very best, rubrics provide learners with standards and expectations they can use to evaluate their performance while completing the assignment.

You can find myriad rubrics for every subject on the web, and in print materials designed for educators. However, the most useful rubrics are usually those you create yourself. Not only can you craft them to exactly meet the goals of your course or course module, but the process of designing a rubric can help you clarify for yourself exactly the criteria you will use to evaluate your learners work.

In his article Designing scoring rubrics for your classroom. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, Craig Mertler (Bowling Green State University) explains the difference between a rubric and a checklist, differentiates between holistic and analytic rubrics and describes a step by step process for designing your own assessment rubric.

Washington State University has developed a critical thinking rubric that can be adapted to reflect critical thinking processes.

Example: In Practice

Engaging Learners in Online Discussion

Assuming you have already considered the role of discussion in helping learners meet the course objectives, you'll want to follow that up with good questions. Questions are at the heart of the critical thinking process and responding to good questions promotes learning.

Good discussion questions are generally open-ended and exploratory in nature, often requiring learners to apply and integrate information from multiple resources, including prior life experiences. Good questions may also be provocative and can be looked at from multiple perspectives.

McMaster University offers some tips for developing good inquiry questions

Penn State University offers some good strategies for online discussion.

University of Waterloo provides some ideas for promoting inquiry through discussion and group work.

Your Feedback

Please take a moment to answer a 5 question survey.

License

|

|