Documentation:Creating the Online Learning Environment/Learning Module

Introduction

In this module, we begin to explore the roles and functions of an online instructor or facilitator. The module introduces the “community of learning” model to help us think about the necessary components of an effective online educational community: cognitive presence, social presence and teaching presence. We'll also touch on open learning contexts to illustrate some of the additional considerations involved in creating and sustaining open environments.

It continues by describing the important ways that online facilitators can assist in the development of the learning community by helping learners find their way, create and share their ‘online identities’, and by modelling and sustaining the social context or ‘culture’ of the online course.

Learning Objectives

This module introduces the roles and functions of an online educator. Participants will explore strategies for encouraging the development of a community of learners and facilitating/participating in online interactions.

These objectives are intended to be an introductory exploration of these strategies.

At the end of this module, participants will be able to:

- identify the important components of a "community of inquiry".

- understand the value of maintaining an effective online presence as an instructor.

- identify examples of three key functions of an effective moderator/facilitator: contextualizing, monitoring and management.

- identify examples of some of the additional considerations for educators in open online learning environments.

Readings

- Anderson, T. (2004). Teaching in an Online Learning Context. In T. Anderson & F. Elloumi (Eds.). Theory and Practice of Online Learning, pp. 273-294.

- Cormier, A., Siemens, G. (2010). Through the Open Door: Open Courses as Research, Learning and Engagement.EDUCAUSE Review, vol. 45, no. 4 (July/August 2010): 30-39

- Dawson, S. (2006). Relationship between student communication interaction and sense of community in higher education. Internet and Higher Education, 9(3), 153-162.

- Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T. & Archer, W. (2000). Critical Inquiry in a Text-based Environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2), 87-105.

- Xin, C. & Feenberg, A. (2006). Pedagogy in Cyberspace: The Dynamics of Online Discourse. Journal of Distance Education 21 (2):1-25

Links

- Effective Online Facilitation (Australian Flexible Learning Quick Guide Series, 2003)

- The Moderator’s Homepage: Resources for Moderators and Facilitators of Online Discussions

- The Virtual Professor: Using Discussion Forums & Chat Tools

- Hutchins, H. (2003). Instructional Immediacy and the Seven Principles: Strategies for Facilitating Online Courses. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, Volume VI, Number III.

- Brown, R. E. (2001). The process of community-building in distance learning classes. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 5 (2).

- Gilly Salmon's 5 stage model for online moderation

Media

Listen to John Campbell from Purdue University talk about the importance of building community in creating a successful online course (duration: 2 min:37 sec).

More video from: COTS Competencies for Online Teaching Success World Campus Penn State PSU Faculty Development

Teaching in an Online Context

As Terry Anderson points out, “learning and teaching in an online environment are, in many ways, much like teaching and learning in any other formal educational context” (2004). The difference, he argues, is that the online environment creates a unique environment for teaching and learning: one that is flexible (time and place can vary), multimedia rich, and communications rich. Taking that notion a step further, Cormier and Siemens (2010) among others, propose the notion that as educators experiment with social media and interactive pedagogies, the whole notion of a course as THE vehicle for learning is challenged. Educators are grappling with questions around effectiveness and engagement. Where does the learning happen? By reading texts or viewing lectures online? Through discussions with peers and facilitators? In self organized "study groups" or chat sessions? What types of learning environments best support a full range of these activities? At the very heart of the matter is the broadly accepted view that people learn best in the context of networks or communities of people.

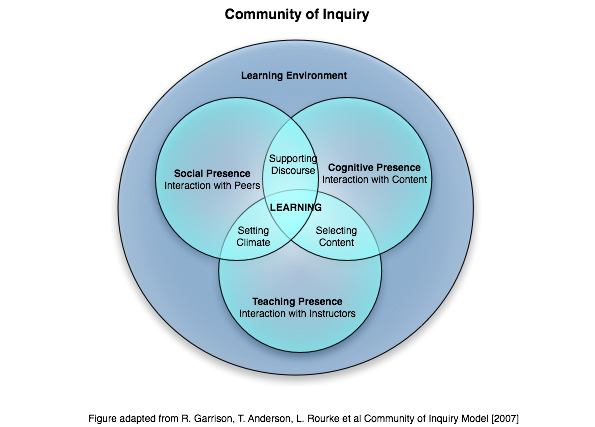

A very useful schema for thinking about the creation of an effective online educational community was developed by Garrison, Anderson and Archer (2000) based on extensive qualitative and quantitative research work undertaken at the University of Alberta (for more papers resulting from their research, see http://www.atl.ualberta.ca/cmc). This conceptual model is called the “community of inquiry” model:

This model postulates that deep and meaningful learning results when there are sufficient levels of three inter-related “presences” in a virtual learning environment:

- Social presence: this relates to the creation of a supportive environment in which learners feel able to express their ideas and collaborate on construction of new knowledge. In the absence of social presence, learners feel unable to disagree, share viewpoints, explore differences or accept support and confirmation from peers or facilitators.

- Cognitive presence: this is the creation of an environment that promotes critical thinking in relation to the content area at hand.

- Teaching presence: describes the creation of an instructional relationship appropriate to the learning community and the topic at hand. It is defined as the “design, facilitation, and direction of cognitive and social processes for the purpose of realizing personally meaningful and educational worthwhile learning outcomes” (http://communitiesofinquiry.com)

Look closely at the model again. Note how the instructor/facilitator plays a key role in both ‘setting the climate’ and ‘selecting the content’ of an educational experience. Open educators would call this content selection "curating" since much of the content may be freely available on the internet. It has become quite clear that early fantasies of computers ‘replacing’ educators are, simply, fantasy.

It's worth noting that in different contexts, the ‘educators’ involved in online learning have different names. In the UK, and parts of the world with historic and linguistic ties to British English and British education, it is common for online educators to be referred to as ‘tutors’ – a term which in British English is relatively benign. In North America (and parts of the world who are heavily influenced by North American language and educational systems), online educators are more commonly referred to as ‘instructors’, especially in the higher education context, although as you will see, theory and training places heavy emphasis on the ‘facilitator’ role that instructors play.

In adult and continuing education, both face-to-face and online, it is common for educators to be called 'facilitators', to highlight their primary role as a helper or enabler who assists a group to achieve their best thinking, rather than as ‘content experts’.

In courses offered by the UBC Centre for Intercultural Communication, the educators who work directly with learners are also called ‘facilitators’, although most also have content expertise that they contribute where appropriate. Each course is also ‘managed’ by a moderator, who makes sure that course logistics proceed smoothly, and who liaises with facilitators and students to keep things on track.

You will notice different terminology in the various resources linked to these course materials, but the principles and practices they suggest are nevertheless relevant for facilitators working online in a variety of contexts.

Exploring the Model

Pause here to read both the Garrison et al (2000) paper, especially the sections outlining the three ‘presences’ as well as the Cormier/Siemens article.

- Cormier, A., Siemens, G. (2010). Through the Open Door: Open Courses as Research, Learning and Engagement.EDUCAUSE Review, vol. 45, no. 4 (July/August 2010): 30-39

- *Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T. & Archer, W. (2000). Critical Inquiry in a Text-based Environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2), 87-105.

You might also like to explore the Community of Inquiry website that summarizes these ideas and links each summary to the authors’ more detailed papers on the topic.

Social Presence, Social Context

It is generally accepted that the social context of learning greatly affects the nature of learning activities and outcomes (Garrison et al, 2000), and the pedagogical benefits of participation in learning communities are now well documented. For example, learning communities have been linked to reduced attrition, the promotion of critical thinking skills, and facilitation of the achievement of learning outcomes (see Dawson, 2006 and references therein).

Contemporary educators are therefore increasingly embracing socio-constructivist practices which emphasize learning as a social and interactive activity. Inspired by this philosophy of pedagogy, increased importance is placed on fostering community in both face to face and online learning contexts. However, while we are presenting these ideas here, it is important to recognize that other theoretical perspectives have value and may offer some additional insights for you as you think about your own teaching practice.

Social constructivist theory builds on the early work of education researchers such as Vygotsky and Piaget. It goes far beyond the notion that good learning ‘happens’ by providing isolated learners with reading material.

Constructivist theory argues that:

- Learners are unique, complex and multidimensional individuals

...with unique needs and backgrounds; this uniqueness and complexity should be encouraged

- The background and culture of the learner are very important

...so learners are encouraged to arrive at their own version of the truth, influenced by his or her background, culture or embedded worldview. This also stresses the importance of the nature of the learner's social interaction with knowledgeable members of the society.

- Learners must become increasingly responsible for their learning

...so the learner must be actively involved in the learning process, unlike previous educational viewpoints where the responsibility rested with the instructor to teach and where the learner played a passive, receptive role.

- Sustained motivation for learning depends on the learner’s confidence

...paraphrasing Vygotsky, learners should be challenged within close proximity to, yet slightly above, their current level of development. By experiencing the successful completion of challenging tasks, learners gain confidence and motivation to embark on more complex challenges.

- Instructors must be facilitators, not ‘teachers’

...when a teacher gives a didactic lecture which covers the subject matter learners are passive recipients; a facilitator, on the other hand, helps the learner to get to his or her own understanding of the content, and learners play an active role in the learning process.

- Learning is an active, social process

...in which learners discover principles, concepts and facts for themselves, through dynamic interaction between task, instructor and learner

Constructivist scholars emphasize that individuals make meanings through the interactions with each other and with the environment they live in. Knowledge is thus a product of humans and is socially and culturally constructed. Learning is not a process that only takes place inside our minds, nor is it a passive development of our behaviours that is shaped by external forces. Meaningful learning occurs when individuals are engaged in social activities.

Optimal learning environments therefore do not simply create opportunities for individual learners to engage intellectually with course materials, or encounter their world as isolated selves – selves that lack “community, tradition and shared meaning” (Martin, 2004). Rather, optimal learning environments permit dynamic interaction between instructors, learners and tasks, and offer learners opportunities to create their own understanding through interaction with others, highlighting the importance of community, culture and context in knowledge construction.

Questions for Reflection:

In what ways might social presence be perceived quite differently in open vs. traditional course contexts? Who may be additional participants in an open learning context? What social influences enhance or detract from the learning environment? Why do you think that is?

Creating Social Presence

Online facilitators and instructors play important ‘social’ roles that are critical to the development of an effective learning environment:

- They must help learners create their individual ‘social presence’ in the online classroom, so that they participate as ‘real people’ in engaged collaborative discourse with peers – allowing learners to perceive themselves as a learning community.

- They must facilitate creation of, and sustain, the social context of learning – nothing less than the ‘culture’ of the course!

Creating Online Selves

The presentation and sharing of one's individual identity is intimately connected to the development of community or ‘sense of community.' Communities are not made up of homogeneous anonymous beings between whom communication and interaction ‘happens.' Rather, they are a heterogeneous mixture of individuals who may or may not share common values, worldviews, or perspectives.

Developing a sense of community demands that individuals come to know each other, and learn about their similarities and differences. Some educational researchers use the notion of transactional distance as a measure of learners' sense of community:

Transactional distance is the cognitive space between learning peers, teachers and content in a distance education setting. Coined by Michael G. Moore in 1980, transactional distance is a function of dialog and structure in distributed adult learning settings. Distance decreases with dialog and increases with structure so that a classroom with high interaction and less rigid format will be more engaging to learners. Wikipedia, 2007

Creating an online ‘self’ is a challenge, however, because we are very used to relying on material elements to give clues about our identity or at least to motivate curiosity, interest, and introductions: skin colour, complexion, body type, clothing and style, jewelery and other adornments, to name but a few. Our body language can also give clues about our character and about our comfort level in an educational setting: Casual or stiff? Bored or alert? Formal or informal? Shy or confident? Moreover, in interpersonal encounters, an individual’s authenticity – a term that in English connotes ‘truth’ and ‘accuracy of (self)representation’ and ‘trustworthiness’ – is supposed to be guaranteed by physical presence and the evidence of the senses.

But as we know, in the text-based communications of a virtual learning environment, bodily markers of identity such as physical attributes and vocal accent, are often invisible and bodily participation in gesture and ritual is usually impossible. The physical body is, in effect, “banned from the Internet."

Yet, study after study has shown that over time participating in online courses, learners’ sense of community increases, and their feeling of transactional distance decreases. For example, Chen’s (2001) quantitative study of adult learners in a web-based course demonstrated that 'extent of interaction' and 'skill level with the Internet' were the only two significant factors influencing learners’ perception of transactional distance.

In other words, it takes time and practice to ‘incorporate’ yourself online: to learn new ways of presenting your own identity, and of ‘getting to know’ others.

Advice from UBC’s Centre for Teaching, Learning and Technology

The online education experts at UBC’s Centre for Teaching, Learning and Technology offer the following advice to online instructors and facilitators for creating their own ‘presence’ online:

The establishing of instructor presence is a process. The process may begin with some sharing of information about:

- You and your background.

- Your expectation for interaction with learners.

- Your style of teaching within the context of this course.

Some first steps in the process are:

- The development of a biography – describing your background, interest in the course material, and (perhaps) something about you and your life which you may want your learners to know about.

- Your first contact with learners (via telephone, email and/or posting within the course website). This should be welcoming, an opportunity for students to seek clarification from you regarding course requirements or content and a chance for you to impart something about who you are and opening the door for communication so that you can get a sense of who they are.

In addition, if you intend to communicate regularly with students online, you will want to consider:

- Regular posting of announcements. This gives students guidance and keeps them on track.

- Letting students know your online teaching style; whether you will be posting every day or weekly; whether you will respond to each post or only those where clarification, guidance, or comment is required.

Please refer to the Introducing Yourself to Learners section of the CTLT website for more information.

Engaging Learners

Xin & Feenberg agree that online facilitators are most challenged by their responsibility for developing the social aspects of an engaged and collaborative online learning environment. These authors suggest that online leadership and motivation should be the key goals of instructors/facilitators in this regard. Managing a successful online community requires strong but not overbearing leadership, through complex communicative interactions. And effective leadership by a facilitator or instructor is essential for keeping participants absorbed and keeping “the game” of collaborative discourse going.

What enables online community in education is not so much the bonds of sentiment formed from personal intimacies, but the deeply satisfying pleasure of engrossment in a dialog game. This, in turn, creates the emotional bond of community.

(Xin & Feenberg, 2006, p. 17)

Most usefully, these authors describe the different kinds of moderating practices that effective online facilitators make use of. They describe three categories of moderating functions:

- Contextualizing functions (setting the context for the learning community: creating a shared framework of roles and expectations, building ‘course culture’)

- Monitoring functions (helping participants know if they are fulfilling expectations)

- Meta functions (management of communications, ‘repair’ of challenging situations, summarizing ideas)

Xin & Feenberg offer an explanatory table in which they elaborate on these functions in more depth.

Contextualizing:

- Opening discussions. The moderator must provide an opening comment that states the theme of the discussions and establishes a communication model. The moderator may periodically contribute “topic raisers” or “prompts” that open further discussions in the framework of the forum’s general theme.

- Setting the norms. The moderator suggests rules of procedure for the discussion. Some norms are modeled by the form and style of the moderators opening comments. Others are explicitly formulated in comments that set the stage for discussion.

- Setting the agenda. The moderator manages the forum over time and selects a flow of themes and topics of discussion. The moderator generally shares part or all of the agenda with participants at the outset.

- Referring. The conference may be contextualized by referring to materials available on the Internet, for example, by hyperlinking, or offline materials such as books.

Monitoring

- Recognition. The moderator refers explicitly to participants comments to assure them that their contribution is valued and welcome, or to correct misapprehensions about the context of the discussion.

- Prompting. The moderator addresses requests for comments to individuals or the group. Prompting includes asking questions and may be formalized as assignments or tasks. It may be carried out by private messages or through public requests in the forum.

- Assessing. Participants accomplishment may be assessed by tests, review sessions, or other formal procedures.

Management

-

Management or meta-functions are those that pertain to the overall management of communication, including repair of challenging situations when needed. These functions include:

- Meta-commentingMeta-comments include remarks directed at such things as the context, norms or agenda of the forum, or at solving problems such as lack of clarity, irrelevance and information overload. Meta-comments play an important role in maintaining the conditions of successful communication.

- Weaving The instructor summarizes the state of the discussion and finds threads of unity in the comments of participants. Weaving recognizes the authors of the comments it weaves together and often implicitly prompts them to continue along lines that advance the conference agenda.

- Delegating Certain moderating functions such as weaving can be assigned to individual participants to perform for a shorter or longer period.

The Instructors' Role In Open Learning Contexts

Dave Cormier and George Siemens in their 2010 article for the Educause Review describe the role of the educator in somewhat different terms:

Open learning does not negate the role of the educator. Instead, open learning adjusts the role of the educator with respect to access to new content and engagement tools now under the control of the learner. Educators continue to play an important role in facilitating interaction, sharing information and resources, challenging assertions, and contributing to learners' growth of knowledge. Through The Open Door: Open Courses as Research Learning and Engagement - EDUCAUSE Review, vol. 45, no. 4 (July/August 2010): 30-39

The table they provide, illustrates the various (and somewhat unique) facets of teaching in an environment that is highly flexible and learner driven.

| Educator Role | Activity of Educator | Tactics and Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Amplifying | Drawing attention to important ideas/concepts | Twitter, blogs |

| Curating | Arranging readings and resources to scaffold concepts | Learning design, tutorials, adjustment of weekly activities to reflect course flow |

| Wayfinding | Assisting learners to rely on social sense-making through networks | Comments on learners' blog posts, help with social network formation, "live slides" method* |

| Aggregating | Displaying patterns in discussions and content | Google Alerts, RSS reader, visual tools (e.g., Many Eyes) |

| Filtering | Assisting learners in thinking critically about information/conversations available in networks | RSS reader, discussion of information trust, conceptual errors |

| Modeling | Displaying successful information and interaction patterns | All use of tools and activities to reflect educators' modeling of appropriate practices |

| Staying Present | Maintaining continual instructor presence during the course, particularly during natural activity lulls | Daily (or regular newsletter), activity in forums, video posts, podcasts, weekly live sessions in synchronous tools (e.g., Elluminate) |

Moderating Online Discussions

Gilly Salmon has developed a 5 stage model describing the stages and the role of the moderator or instructor in an online course. The model emphasizes both the goals of the learner and the role of the moderator or instructor at each stage.

Questions for Reflection

In thinking about Salmon's model, how is it similar to the frameworks proposed by Xin and Feenberg or open educators Siemens and Cormier? How is it different? Regardless of the model used, what are the most important features involved in creating effective online learning environments?

Examples in Practice

Setting the Context

What does this look like in real practice?

Often, new online learners are nervous about being the ‘first to post’. You can break the ice by posting the first message. You might ask a few ‘leading questions’ related to current materials, and express interest in hearing learner’s ideas. Enthusiasm helps to set the tone!

|

Your style and approach (Friendly? Formal? Questioning? Personal? Supportive? Critical?) will powerfully influence the way new learners respond to you and to each other.

You also play an important role in ‘reminding’ people about course norms, but remember this can be done discreetly and positively:

|

Your early responses also shape the online discourse patterns of your course: it is important to craft messages carefully, to encourage further thinking and reading:

|

Monitoring

What does this look like in real practice?

‘Feedback’ is acknowledged as one of the simplest but most powerful tools for learning, whether online or offline. In his widely respected book, “How People Learn”, Bransford and colleagues (1999) explain:

In order for learners to gain insight into their learning and their understanding, frequent feedback is critical: students need to monitor their learning and actively evaluate their strategies and their current levels of understanding.

In the online context, learners typically receive feedback from you is from direct written responses to their writing or messages (or, in some cases, from receipt of a grade). Indeed, research has shown that learners whose messages frequently go unacknowledged report feeling demotivated and unsupported in their learning. While you need not (and probably cannot) respond to every single message a learner posts, it is important to plan to respond strategically at points where they accurately express key ideas, or where they clearly fail to meet expectations or misunderstand concepts. Again, this need not be done harshly:

|

In a similar way, in an online course, your learners are invisible unless they ‘appear’ in online discussions or other course-based communications. Part of your ‘prompting’ and ‘assessing’ role may also be to contact ‘missing’ learners privately to encourage participation, note deadlines, and add reminders about course expectations.

Management

What does this look like in real practice?

As in a face-to-face meeting or classroom, the facilitator plays a key role in helping the group reach a clear shared understanding. Again, your comments play an important ‘feedback role. They need not be extensive (in fact, sometimes brief comments are more effective) but help to gently guide group discussion:

|

Different facilitators play their ‘weaving’ role in different ways. Some prefer to post a ‘closing’ message at the end of each topic or unit of work. Others highlight important messages posted by participants during the preceding discussion. This is another area where you can use your skill and creativity to best meet the learning needs of the group without having to post redundant summary material.

Open Learning Environments

Here are some examples of courses taught in open environments, using tools and platforms other than the university supported learning/course management systems:

At UBC

- Wikipedia:WikiProject Murder Madness and Mayhem

- David Vogt and David Porter's : Ventures in Learning Technology - ETEC 522

Other Examples

- George Siemens and Stephen Downes' Connectivism and Connective Knowledge

- Alec Couros' Social Media and Open Education

Your Feedback

Please take a moment to answer a 5 question survey.

License

|

|